Summary: 1. Introduction. 2. Article Development. 3. Final Considerations. 4. References.

Sumário: 1. Introdução. 2. Desenvolvimento do artigo. 3. Considerações Finais. 4.Referências.

1 INTRODUCTION

There are considerations implying that if the spending agencies adequately mobilize the resources they receive, concrete effects will be observed, since the use of allocated public resources entails being able to unite the decisions (steer) of the provision of services (row) in an harmonious in general, and with respect to the function of judicial entities in particular, fundamentally under the connotation of being used efficiently and effectively by those who carry out the management, even more so if they are oriented under the sieve of doing it for results.

This approach has the objective to recognize if there is a relationship between the progress of the Rule of Law of Latin American nations and the implementation of results - based budgeting in judicial institutions. This notion entails the hypothesis of discerning globally if, after the empirical analysis, the expected results have been achieved, complemented by the mechanisms of perception of the Rule of Law.

The methodology used is based, on the one hand, on a regressive diachrony that allows us to observe antecedents to explain and contextualize the evolution of the Rule of Law, and on the other hand, comparative law analysis to find the judicial institutions in conjunction with the Budget with the New Management. Public and Results-Based Management. This will configure the analysis to be carried out, building and comparing the approach regarding the budget function with indicators of the Rule of Law that are used for this area.

The results obtained from the respective identifications derived from the regressive diachronies presented and the shared comparisons must be taken with moderation since, although a clear relationship can be observed, the danger is to generate a cognitive dissonance of correlation that does not necessarily imply causality. Therefore, the results of an exploratory nature give us an idea of where we place the indicated judicial institutions, their institutional relationship with the budgetary dimension and the cognitive integrations to understand these elements from the perspective of management by results, especially before the elements of State of Law that have been shown to contextualize, that although they are not unique, they give us a kaleidoscopic idea of the relationship for the understanding of the development of judicial institutions. Accordingly, there is an international consensus that confirms recognizing the Rule of Law as a significant and important element to locate the justice sector and, in turn, its budget component in terms of specific results, being informative to the extent that they are observed in the practice for those responsible for influencing the sector.

2 ARTICLE DEVELOPMENT

The substantive activity of the jurisdictional authority is the fulfillment of its function within the Judiciary, therefore, the existence of mechanisms to evaluate and enhance the performance of judges in their work is essential for the proper conduct of the judicial institution, but Of course there are preconditions. In this case, it must be considered that there can be no efficiency if there is no rule of law, as well as there can be no efficiency if other elements are not considered, such as the functioning of judicial institutions in their context and structure, as well as application, formal legitimacy or functional that the respective institution has, that is, correlated with the elements that allow focusing the available resources at its disposal to be able to exercise its function.

It is important to recognize the New Public Management (NPM) in relation to the Rule of Law as an instrument that aims to support the economic, political and social development of any country, and that in the region has to be oriented towards addressing three major problems: the consolidation of democracy, the need to resume economic growth and the reduction of social inequality, guaranteeing social inclusion. To address these challenges, the Latin American States must adapt their organization and operation to the new realities, learning from the mistakes and successes of the various recent experiences and adopting a new model of public management that recovers the capacity of the Ibero-American public administrations as useful instruments and effective at the service of the common good or general interest of their respective societies (CLAD, 2008).

Making a balance of the advances in administrative reforms, it is shown that structural adjustment, whose ultimate objective was to reduce the size of the State, did not solve a series of basic problems of the Latin American countries. For this reason, a second generation of reforms has been proposed, with the aim of rebuilding the state apparatus. The current diagnosis affirms that the State continues to be a fundamental instrument for the economic, political and social development of any country, even though today it must function in a different way from that contemplated in the national-developmentalist pattern adopted in much of Latin America, and the social-bureaucratic model that prevailed in the post-war developed world (CLAD, 2008:7), thus attempting a third way between neoliberal laissez-faire and the old social-bureaucratic model of state intervention.

This path is supported by the implication of a Management Reform to be able to improve the management capacity of the State while increasing the democratic governance of the political system, which seen from the institutional perspective, the management reform links the reform of the institutions or, said in a major tone, the reform of the State (AGUILAR, 2006:166). In this regard, it is taken with emphasis what is inferred when considering the New Public Management as a philosophy and current of modernization of the public administration that has been developed since the 1980s, oriented to the search for results and efficiency (CLAD, 2008).

However, other alternatives arise as elements that refer to the public service, for example, governance equated to a minimum State, corporate governance (of an organization), good governance, there are even differentiations regarding what governance would imply with respect to governability and governance with respect to governing, where not all governance structures are capable of producing governability and not all governability guarantees development (Prats I Catalá, 2005:139), being its characteristic it is essential to consider the possibility of being the answer to the inability of the New Public Management to settle the problems that have been inherited from the bureaucratic administration (PÉREZ, 2013:214). The approach is better identified if we can discern the elements that make the difference with respect to the perspectives of classical analysis and New Public Management:

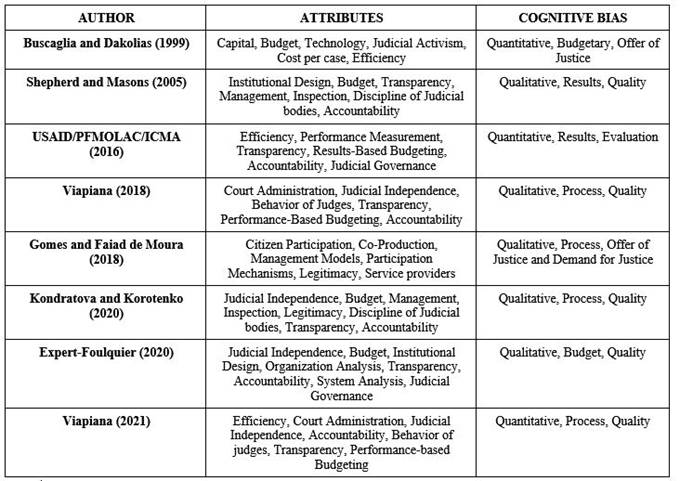

TABLE 1 COMPARISON OF APPROACHES FOR JUDICIAL INSTITUTIONS

Note: Own elaboration based on ATRIO, Jorge and PICCONE, María, De la Administración Pública a la Gerencia Pública. El porqué de la necesidad de gestionar la transición, Revista del CLAD Reforma y Democracia (42), 2008, ISSN: 1315-2378, p. 191, Available at: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=357533673006 (Accessed: August 31, 2022); DENHARDT, Janet et al, The new public service: serving, not steering (2th ed.), Routledge, Reference and Research Book News, 18(1), p. 28-29, 2007; CONTINI, Fransesco and MOHR, Richard, Reconciling Independence and Accountability in Judicial Systems, Utrecht Law Review, 3(2), 2007, p. 26-43, Available at: https://heinonline-org.bucm.idm.oclc.org/HOL/Page?public=true&handle=hein.journals/utrecht3&div=15&start_page=26&collection=journals&set_as_cursor=0&men_tab=srchresults (Accessed: August 31, 2022).

This transition between the bureaucratic model and the new public management has implied from the budget arena a budget system for the achievement of results in the sense that the information generated can be used in decision making to allow the development of institutional capacities, understanding this as the process by which the knowledge, instruments, processes, practices, abilities and skills of those who make up the organizations are increased and renewed and knowledge of the budget serves as an implementation tool to achieve the planned results for the benefit of the administrators.

The foregoing poses another challenge which implies that judicial institutions, given the uniqueness of the service, may pay little attention to issues related to performance and accountability2, since the relationship between accountability and judicial independence may be a double-edged sword, which can be an incentive, but also an undesirable factor of influence on the Judiciary in the worst of cases, but in the best of them, a catalyst for judicial independence legitimized with the surrender accounts3, and in some cases there may be doubt as to the relationship between structure and quality4.

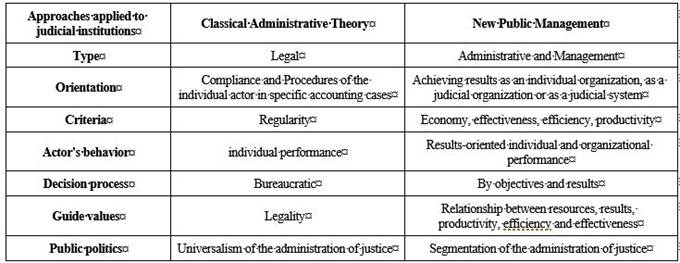

Therefore, knowing the administrative work that possibly generates better results when combined with the institutional changes of the judicial work is desirable, since in practice the quality of justice can be complemented when it focuses on the management of the judicial system with indicators that address both the actions and cognitive biases derived from their management. In this regard, there is empirical evidence that shows us the relationship between the institutional elements and their budgetary nature according to the following:

In order to observe this relationship between the rule of law and the budget, it is important to recognize the current state of this first element. In this regard, the Rule of Law Index assigns scores and rankings to countries for the eight factors (limits to government power, absence of corruption, open government, fundamental rights, order and security, regulatory compliance, civil justice, and criminal justice), which lead to the development of an Index, which is based on information from 139 countries and jurisdictions, being the only measurement that is built from primary data that reflects, first-hand, the perspective and experience of people in their lives (designed for a broad audience that includes legislators, civil society organizations, and academics, among others) as a tool used to identify the strengths and weaknesses of each country, as well as to promote public policies that strengthen the Rule of Law defined5.

Now, for the Latin American case, the following results are presented where the table shows the scores and rankings of the Rule of Law Index from 2014 to 2021 in alphabetical order. The scores range from 0 to 1, where 1 indicates the highest adherence to the Rule of Law. For the definition of the Rule of Law and the methodology used in the Index, this is based on surveys answered by professionals and together, they produce timely and first-hand information to reflect the experience and perception of people on issues related to the government, police, courts, transparency, corruption, and victimization, among others6. The progression of index results is presented:

TABLE 3 WORLD JUSTICE PROJECT IN LATIN AMÉRICA 2014-2021

Note: Own elaboration based on the data provided by the INDEX OF LAW, World Justice Project (WJP), Available at: https://worldjusticeproject.org/our-work/research-and-data(Accessed: August 31, 2022). This is a quantitative assessment tool designed by World Justice Project to provide a detailed and comprehensive picture of the extent to which countries adhere to the rule of law in practice. (*) Implies that the country was not evaluated for the respective year.

Factors in the WJP Rule of Law Index include: 1. Restrictions on government powers 2. Absence of corruption 3. Open government 4. Fundamental rights. 5. Order and security 6. Compliance with regulations 7. Civil Justice 8. Criminal Justice. (Data is collected for a Ninth factor, Informal Justice, but is not included in the aggregate scores and rankings. This is due to the complexities of these systems and the difficulties in measuring their fairness and effectiveness in a matter that is both systematic and comparable across countries). The following dataset presents the factor and subfactor scores for the countries and jurisdictions included in each iteration of the Index since 2012, where 1 means the highest score and 0 means the lowest score. Scores across iterations of the Index are not strictly comparable. This is mainly due to three reasons. First, countries are scored relative to other countries in the sample. Ninety-seven (97) countries/jurisdictions were included in the 2012-2013 data set. Ninety-nine (99) countries/jurisdictions were included in 2014. One hundred and two (102) countries/jurisdictions were included in 2015. One hundred and thirteen (113) countries/jurisdictions were included in 2016 and in 2017-2018. Second, the construction of the indicators has been slightly revised with the publication of each report. Third, the underlying survey instruments have been slightly revised each year. For these reasons, caution is advised when comparing scores over time.

Changes in the construction of the main indicator from 2012-2013 to 2014: A) Sub-factor 1.1 “The powers of government are defined in the fundamental law” was removed from the conceptual framework. B) Subfactors 5.1 “Crime is effectively controlled”, 8.1 “The criminal investigation system is effective” and 8.2 “The criminal sentencing system is timely and effective” includes new data from two questions based on survey experience of general population. C) In the construction of subfactors 3.1 “Laws are published and stable”, 8.6 “The criminal system is free from undue government influence” and 7.4 “The civil system is free from undue government influence”, several questions were eliminated ( five questions) in the first case and one question in the second and third cases). D) In the construction of subfactor 5.2 “The civil conflict is effectively limited”, the categorical coding of the variables “deaths in combat”, “unilateral casualties”, “deaths due to terrorism” and “terrorism events” was revised.

Changes in the construction of the main indicator from 2014 to 2015: A) The order of the factors for “Open government” and “Order and security” was modified, so that “Open government” was included as factor 5 and “Order and security “ were included as factor 3.B) Several changes were made to the conceptual framework of the “Open Government” factor. First, the category “Published Laws and Government Data” is an expansion of the category labeled “Laws are published and stable” in previous editions of the Index. For the 2015 report, the definition of the concept has been expanded to include new information on the quality and accessibility of information published by the government in print or online. Second, the “Right to Information” category, previously called “Official information is available upon request,” was expanded to include new survey questions about whether government information requests are granted within a reasonable period of time, if the information provided is relevant and complete, and if requests for information are granted at a reasonable cost and without payment of a bribe. Third, the “Civic Participation” category, previously called “Right to Petition Government and Public Participation,” was expanded to include survey questions on freedom of opinion and expression, and freedom of assembly and association. Fourth, the category “Complaint Mechanisms” was introduced and measures whether individuals can make specific complaints to the government about the provision of public services or the performance of government officials. The “Laws are Stable” category, which was previously included as part of the open government factor in the Rule of Law Index, has been removed.

Changes in the construction of the main indicator from 2015 to 2016: A) This year, the WJP added 11 countries from Latin America and the Caribbean to the Index. These countries are: Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, St. Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago. B) To allow for easier comparison across years, the 2016 scores were normalized using the Min-Max method with a base year of 2015. Once normalized, the scores were aggregated from the variable level to the factor level to Produces the country's final scores and rankings.

C) This year, some changes were made to some of the indicators and questions in the Index. The most important changes occurred in subfactors 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, 5.1 and 6.4. As a result, the scores for these subfactors cannot be compared across years. Overall, 94% of the questions remained the same between 2015 and 2016.i) In the construction of sub-factor 3.1 “Published Laws and Government Data”, eight questions were removed and the Open Data Index was added. Subfactor 3.1 now has 10 questions and is divided into two components: Published Laws and the Open Data Index. The Open Data Index is produced by Open Knowledge International and measures the state of open data in countries around the world from the perspective of citizens. In the construction of subfactor 3.2 “Right to information”, six questions were deleted, two questions were added and one question was replaced. Subfactor 3.2 now contains 22 questions. In the construction of subfactor 3.3 “Civic participation”, three questions were deleted and two questions were added. Subfactor 3.3 now contains 30 questions. ii ) In the construction of subfactor 5.1 “ Crime is effectively controlled”, two questions were deleted. Additionally, the kidnapping threat rating, compiled by NYA International, has been added to sub-factor 5.1 to replace the previous kidnapping indicator. Subfactor 5.1 now contains eight questions. iii) In the construction of subfactor 6.4 “Due process is respected in administrative procedures”, one question was dropped. Subfactor 6.4 now contains four questions.

Changes in the construction of the main indicator from 2017 to 2018. First, countries are scored relative to other countries in the sample. Ninety-seven (97) countries/jurisdictions were included in the 2012-2013 data set. Ninety-nine (99) countries/jurisdictions were included in 2014. One hundred and two (102) countries/jurisdictions were included in 2015. One hundred thirteen (113) countries/jurisdictions were included in 2016 and in 2017-2018. Second, the construction of the indicators has been slightly revised with the publication of each report. Third, the underlying survey instruments have been slightly revised each year. For these reasons, we ask all users to be careful when comparing scores over time.

2019 Leading Indicator Construction Changes. This year, the WJP added 13 countries in North and Sub-Saharan Africa to the Index. These countries are: Algeria, Angola, Benin, Democratic Republic of Congo, Guinea, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Rwanda, and Togo. No new questions or indicators were added to the Index. Overall, 100% of questions remained the same between the 2017-2018 and 2019 editions of the Index. A description of the variables is available at worldjusticeproject.org.

Changes in the construction of the main indicator of 2020. This year, the WJP added Gambia and Kosovo to the Index. No new questions or indicators were added to the Index. Overall, 100% of questions remained the same between the 2019 and 2020 editions of the Index. A description of the variables is available at worldjusticeproject.org.

Changes in the construction of the main indicator of 2021. This year, the WJP added Paraguay for Latin America. A description of the variables is available at worldjusticeproject.org. A detailed description of the process by which data is collected and rule of law is measured is provided in: BOTERO, Juan and PONCE, Alejandro, Measuring the Rule of Law. the World Justice Project - Working Paper Series WPS N. 001,2011, Available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1966257(Accessed on: August 31, 2022).

In accordance with the above, it is established in the study that the effective Rule of Law reduces corruption, protects people from injustice, fights poverty, being the sustenance of communities of equality, opportunities and peace, in addition to serving as the basis of development, of transparent governments that are accountable, and of respect for fundamental rights, noting that, when the rule of law is weak, violence and crime cannot be controlled, the law is applied unfairly, and there is no foreign investment, emphasizing that it is an issue that not only involves lawyers and judges, but is a concept that involves the entire society (Word Justice Project, 2018:10).

For the year 2014, it can be seen that of the 15 Latin American countries included in the study, only 6 countries are evaluated above the regional average (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Panama and Uruguay), while the other 9 (Bolivia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Nicaragua, Peru, the Dominican Republic and Venezuela) are below the respective average, with Uruguay, Chile and Brazil being the best evaluated countries, while Venezuela, Bolivia and Nicaragua are at the bottom.

In 2015 the number of countries evaluated increased, to be thus 17 with the inclusion of Costa Rica and Honduras. Regarding the changes generated between periods, only 7 countries are evaluated above the regional average (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Panama and Uruguay), while 10 (Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Nicaragua, Peru, the Dominican Republic and Venezuela) are below average, with Uruguay, the recently included Costa Rica and Chile, the best evaluated, while Venezuela, Bolivia and the also recently presented Honduras, they are in the last positions of the evaluation.

Later we find the case of the year 2016, a year in which 8 of the 17 countries are above the average for that year. For this period, the novelties are Colombia, having an evaluation above the average together with Peru, while El Salvador is the country that, given its measurement for that year, is now below the average for the region. Regarding the countries with the best and worst evaluation, it can be said that they maintain the same status with respect to the average and position that is maintained for the period 2017-2018, making it clear that the perceptions on the evaluation of the rule of law are maintained with a certain inertia over time with respect to the methodology of the World Justice Project, especially when we also look at the years 2019 and 2020.

For the 2021 period, the global inertia that was maintained on average is broken, since it is the period in which the general average of the weighted general evaluation is lower than its predecessors the number of countries evaluated increases, to be thus 18 with the inclusion of Paraguay. Regarding the changes generated between periods, only 6 countries are evaluated above the average of the region (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, Panama and Uruguay), while 2 are equal to the average (Peru and Colombia) and 10 are below the average (Bolivia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Nicaragua, Peru, Dominican Republic and Venezuela), with Uruguay, Costa Rica and Chile, the best evaluated, while Venezuela, Bolivia and Honduras continue occupying the last positions.

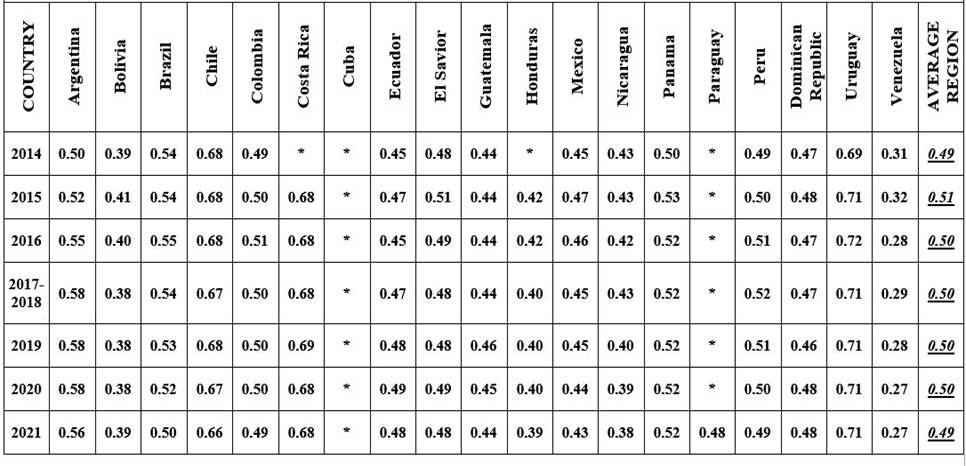

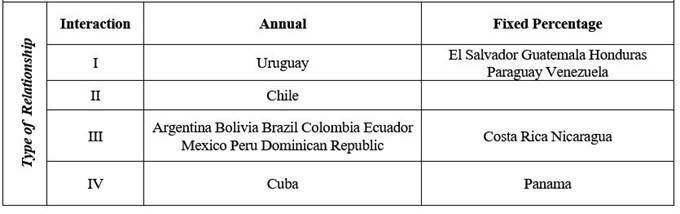

Accordingly, there is an international consensus that confirms recognizing the Rule of Law as a significant and important element to locate the justice sector. In addition to this grouping, it is important to be able to contextualize these results with the institutional elements that refer to each Latin American country, particularly from the budgetary perspective that gives institutional functioning through the application of public resources in the public budget. Next, a diagram is presented where each of the listed countries is located according to the budgetary particularities that emanate from their respective legislation, as well as in type of interaction related to the internal management of the formulation of the budget of the respective judiciary according to the following table:

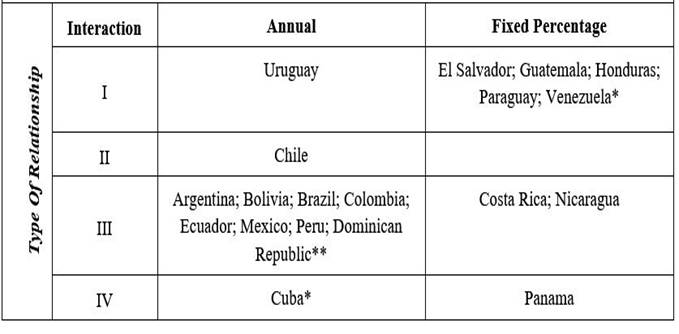

TABLE 4 FORMULATION OF THE BUDGET OF THE JUDICIAL BRANCH IN LATIN AMERICAN COUNTRIES BUDGET ALLOCATION

Note: Own elaboration based on the internal legislation of the respective countries. Depending on the case, some of which can be found in WIPO LEX, Member Profile - Laws, Treaties, and Judgments, Available at: https://wipolex.wipo.int/en/members (Accessed: August 31, 2022).

Two major divisions can be observed. On the one hand, there are the countries that carry out their annual budget as established by their respective legislation, and those that are guaranteed an annual percentage of budget allocation as indicated by their constitutions. In turn, we have a classification by interaction, that is, there are situations in which budget management is carried out directly by the Tribunal or Superior Court of Justice of the respective country, this identified with “I”. At the same time, we identify with “II” the case where the country does not have any type of Council (Judiciary or Magistracy) for the formulation of its respective budget, but it does have an internal administrative entity in charge of it. Then we have with “III” the case of the countries that do have a Council (Judiciary or Magistracy) as an integral organ of the respective Judicial Power, fulfilling the budgetary formulation function within the referred Power. Lastly, we have the cases in which it is not only the respective Judiciary that is in charge of the budgetary function, but also refers to some other actor in a relationship of subordination or cooperation to enable the realization of the budget project indicated with the letter “IV”.

In case I we find Uruguay on the part of the Supreme Court of Justice who directly concentrates said function. El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Paraguay and Venezuela are in the same case. Specifically, in the case of the five, the budgetary functions are assumed directly by the Tribunal or Supreme Court, despite the fact that they have some type of Council within their organization, this being merely one of promotion, surveillance and discipline regarding the actions of the judges who comprise them. These last five countries have a fixed guaranteed budget percentage for their operation.

In group II we only find Chile. This country has the peculiarity of not having a Council of the Magistracy or of the Judiciary as such, however it does have the Administrative Corporation of the Judicial Power (CAPJ), which is an institution at the service of the courts of justice, administering the human, physical, financial and technological resources of the Judiciary, whose management is in charge of a Superior Council, made up of the President of the Supreme Court, who heads it, and four ministers of the highest court, elected by their peers for a term two years old. This Corporation is responsible for the preparation of the budgets and the administration, investment and control of the funds that the Budget Law assigns to the Judicial Power of Chile, which we place within the annual budget allocation.

In III we find the largest group. In particular, we find both countries that formulate an annual budget and countries that have a fixed percentage guaranteed in their respective Constitution. Within the first group we place Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru and the Dominican Republic. In the second group we find Costa Rica and Nicaragua which have a guaranteed budget percentage. In all these cases, they have a Council of the Magistrature or the Judiciary in charge of formulating the annual budget of their respective Judicial Branch. There are particularities of each of the countries, however, they can be located within the respective groups proposed.

In the last group we find Cuba and Panama in IV. In Cuba, due to the peculiarities of its political system, it refers that the final person in charge of preparing the annual budget is the Council of Ministers, which is submitted to the approval of the Assembly of People’s Power. Cuba does have a Government Council in charge of preparing the budget of its popular courts, however this Council, although it has activities very similar to the Councils of the Judiciary or Magistracy7. In Panama, in addition to the particularity of having a guaranteed percentage for its budget, which may not be less than the current income of the Central Government, the Supreme Court of Justice and the Attorney General of the Nation will formulate the respective Budgets of the Judicial Branch and of the Public Ministry, sending them opportunely to the Executive Organ for their inclusion in the project of the General Budget of the public sector. That is, we could refer that in the preparation of the budget, whether annual or fixed, there is the participation of entities external to the Judicial institution for its preparation.

You can see the cases of Paraguay, Peru and the Dominican Republic. These in turn refer to a greater particularity. In Paraguay, the Supreme Court of Justice is responsible for submitting to the Executive Power the preliminary draft of the Budget of the Judicial Power and, in turn, has an extra-power body called8the Council of the Magistracy, which is a different body from the bodies of the constituted powers, it is different from the Judicial Power, different from the Legislative Power and the Executive Power, but notwithstanding these same three organs compose it to some extent, it is not part of the Judicial Power but it does function to integrate the Judicial Power with respect to its officials. In the case of Peru and the Dominican Republic, both have an Executive Council or Council within the Judiciary, while the existence of the National Council of the Judiciary as an entity external to the Judiciary is also possible.

Summing up, to specifically identify the similarities and differences, in countries such as Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica9, Mexico and Nicaragua10, their councils refer to functions of administration, appointment and disciplinary control of judicial personnel. In Uruguay, Venezuela, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Paraguay, the administrative activities are carried out directly by the Tribunal or Superior Court of Justice, also including appointment and control, except in the case of Paraguay since, as we refer to it, the Council of the Judiciary of Paraguay is not included within its Judicial Branch11. Chile refers in its Corporation to the exclusively administrative function of human, financial, technological and material resources12. Cuba does not refer to any Judiciary or Magistracy Council13, however it does have a Government Council hierarchically subordinate to the National Assembly of People’s Power and the Council of State. In Panama, those in charge of preparing the Budgets of the Judicial Branch and the Public Ministry collaboratively are the Supreme Court of Justice and the Attorney General of the Nation, who budget jointly.

Almost all of these councils have, if not a majority, at least a relevant integration of judges, particularly members of the superior courts. The councils of Argentina, Bolivia and Mexico are presided over by the respective presidents of the supreme courts; in Brazil, it is chaired by a minister of the Federal Supreme Court. In such a way that today it is the magistrates of the supreme courts who control the management of judicial systems that are much larger and more relevant than before, when they were under the tutelage of the Executive Power. As a result, the hierarchical structure of the judicial powers in the region is perceived much more in the concentration of these administrative faculties or in civil service matters, than in the jurisdictional ones (VARGAS, 2009: 277-278).

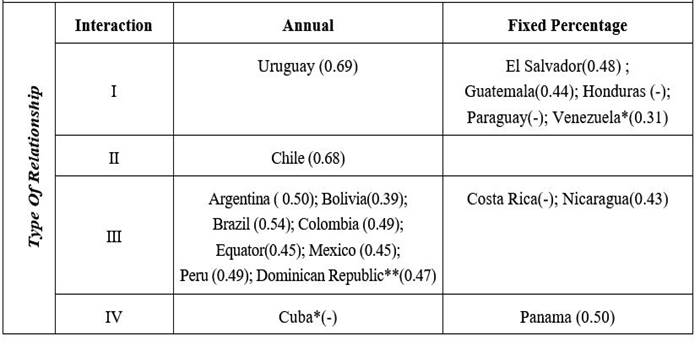

Since we have observed the budget function in Latin American countries, we now integrate the Management by Results element, which not only seeks to improve the structure of incentives that affect the behavior not only of public administrators, but also of judges and their capacity to make decisions, which, together with the budget element, is included within the threshold between budget and performance, which indicates that governments do not budget for results unless they manage for results14. From the above, the following can be identified in relation to what was published by the IDB in 2014 regarding the study called “Presupuestos para el Desarrollo en America Latina”, prepared within the framework of the Program for the Implementation of the External Pillar of the Medium-Term Action Plan Deadline for Development Effectiveness (PRODEV) of the IDB, which includes the Prodev Evaluation System (SEP), a mechanism to measure the Results-Based Management for Development (GpRD) capacity of 16 countries included in the study(Guzmán, 2014:318). The system is based on indicators, grouped into four measurement pillars: Information on performance; Manager skills to achieve results; Results-motivated management; and Use of information in decision making. The countries have been stratified according to the following assessment of the implementation of the methodology, contrasting what has been said with the following scheme where each of the listed countries is located according to the budgetary particularities and implementation of the Results-Based Budgeting methodology that emanate of their respective legislation, as well as in the type of interaction related to internal management in deepening the implementation of the in the judiciary according to the following:

TABLE 5 FORMULATION OF THE BUDGET OF THE JUDICIAL POWER IN LATIN AMERICAN COUNTRIES ACCORDING TO THE IMPLEMENTATION OF PbR BUDGET ALLOCATION

Note: Own elaboration based on the internal legislation of the respective countries. Depending on the case, some of which can be found in WIPO LEX, Member Profile - Laws, Treaties, and Judgments, Available at: https://wipolex.wipo.int/en/members (Accessed: August 31, 2022); GUZMÁN, Marcela et al., Presupuestos para el Desarrollo en América Latina. Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo, 2014, p. 151-198, Available for consultation via internet at the following page: https://publications.iadb.org/bitstream/handle/11319/466/Presupuestos%20para%20el%20desarrollo%20en%20Am%C3%A9rica%20Latina.pdf?sequence=1 (Accessed on: August 31, 2022). (*) Cuba and Venezuela are not considered in the comparison. (**) The Dominican Republic is not considered in the study either, however, it contemplates a medium level of development, which, compared to those evaluated in the scheme, could reach an initial to medium level of implementation for GARCÍA, Roberto. and GARCÍA, Mauricio, La gestión para resultados en el desarrollo. Avances y desafíos en América Latina y el Caribe, Washington, D.C. BID, 2010, p. 3-190, Available at: https://indesvirtual.iadb.org/file.php/349/modulos/La_gestion_para_resultados_en_el_desarrollo.pdf (Accessed on: August 31, 2022).

In order to differentiate the proposed elements, different underlinings are used. In this regard, the advanced implementation level corresponds to dashed underlining, the medium implementation level corresponds to double underlining, and the initial implementation level corresponds to single underlining. In a parallel way, we can understand that there are two large groups, there are the countries that are making their annual budget and those that are guaranteed an annual percentage of budget allocation. There are interactions where the management of the budget is carried out directly between the Court or Superior Court of Justice (I), in turn the case where, since the country does not have any type of Council of the Judiciary or Magistracy, it does have an internal administrative entity in charge of it (II), the case of the countries that do have a Council (Judiciary or Magistrature as an integral organ of the respective Judicial Power III) and finally we have the cases in which it is not only the Judicial Power respective person in charge of the budgetary function, since it is in a relationship of subordination or cooperation to enable the execution of the respective budget project (IV).

Now, according to the document presented by the Inter-American Development Bank, we can verify that a large part of the countries that have a medium and advanced implementation level are countries that carry out an annual budget, while the great conglomerate of countries with a fixed budget has in its most, initial implementation level. This perhaps reflects the paradox of having a guaranteed budget and generating few incentives to implement a results-based methodology. The only exception is Costa Rica, which despite of having a guaranteed budget in a fixed percentage, has had a medium level of implementation, that is, only 1 of the 8 countries type guaranteed budget propose mechanisms for the performance of their jurisdictional activities.

Returning to the Rule of Law Index15, the following results are presented with respect to the Latin American countries where the scores and rankings of the Rule of Law Index for 2014 are presented in this table16 (scores range from 0 to 1, where 1 indicates the greatest adherence to the Rule of Law) being a quantitative tool designed with a multidisciplinary approach (Guzmán, 2014:318) already stated. For this section, it is done exclusively with respect to the year 2014 to maintain consistency with respect to the year in which the study was carried out. Without a doubt, interesting results are obtained from the conformation of possibilities, from the performance in the implementation of the methodology, the type of budgeting with respect to the specific country and justice perception:

TABLE 6 FORMULATION OF THE BUDGET OF THE JUDICIAL POWER IN LATIN AMERICAN COUNTRIES ACCORDING TO THE IMPLEMENTATION OF PbR AND THE RULE OF LAW (WJP) 2014 BUDGET ALLOCATION

Note: Own elaboration based on the internal legislation of the respective countries. Depending on the case, some of which can be found in WIPO LEX, Member Profile - Laws, Treaties, and Judgments, Available at: https://wipolex.wipo.int/en/members(Accessed: August 31, 2022); GUZMÁN, Marcela et al., Presupuestos para el Desarrollo en América Latina. Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo, 2014, p. 151-198, Available for consultation via the internet at the following page: https://publications.iadb.org/bitstream/handle/11319/466/Presupuestos%20para%20el%20desarrollo%20en%20Am%C3%A9rica%20Latina.pdf?sequence=1 (Accessed on: August 31, 2022). (*) Cuba and Venezuela are not considered in the comparison. (**) The Dominican Republic is not considered in the study either, however, it contemplates a medium level of development, which, compared to those evaluated in the scheme, could reach an initial to medium level of implementation for GARCÍA, Roberto. and GARCÍA, Mauricio, La gestión para resultados en el desarrollo. Avances y desafíos en América Latina y el Caribe, Washington, D.C. BID, 2010, p. 3-190, Available at: https://indesvirtual.iadb.org/file.php/349/modulos/La_gestion_para_resultados_en_el_desarrollo.pdf (Accessed on: August 31, 2022).; https://worldjusticeproject.org/our-work/research-and-data INDEX OF LAW, World Justice Project (WJP), Available at: https://worldjusticeproject.org/our-work/research-and-data(Accessed: August 31, 2022). This is a quantitative assessment tool designed by World Justice Project to provide a detailed and comprehensive picture of the extent to which countries adhere to the rule of law in practice as of 2014.

Now, from the point of view of implementation according to the document presented by the Inter-American Development Bank and the perception of justice evaluated in the Index of Law, we can verify that a large part of the countries that have a medium and advanced level of implementation between the countries that carry out an annual budget, in turn, have a perception of justice above the average (for the year 2014 it was 0.49) while the large conglomerate of countries with a fixed budget have, for the most part, initial implementation with a perception of justice less than average.

This reflects a double paradox that implies having a guaranteed fixed budget and generating few incentives to implement a methodology based on results, reflecting a perception of fairness for the year of verification that is lower than the average for the region. The only exception is Panama, which despite having a fixed budget, is one of the countries with the best evaluation in terms of perception of justice. In this regard, it is important to mention that countries such as Costa Rica, Honduras and Paraguay did not appear in the 2014 Index of Justice. Therefore, the results, despite having a certain logic, could be taken with restraint.

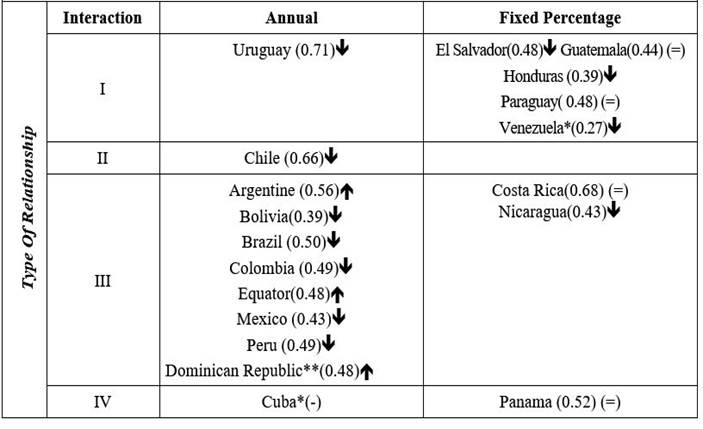

Finally, we have the most recent data from the World Justice Project of 2021, the year in which the evaluation average coincides for the Latin American region for the year with 0.49. This, in addition to being coincidental, raises the possibility of resuming the progress that the perception of justice has had from the year 2014 to the year 2021.

It is important to underline that, although some elements of the methodology have been modified between years as it has been explained, it is undoubtedly still relevant to be able to observe the current status of the measurement given the structural elements that have been spilled with respect to the budget and the implementation of the results-based methodology. In particular, limiting ourselves exclusively between the years that are strictly comparable, the years 2016 and 2021 are taken into consideration to observe the following:

TABLE 7 PROGRESS IN THE FORMULATION OF THE JUDICIAL BRANCH BUDGET IN LATIN AMERICAN COUNTRIES ACCORDING TO THE IMPLEMENTATION OF PbR AND THE RULE OF LAW (WJP) 2021 BUDGET ALLOCATION

Note: Own elaboration based on the internal legislation of the respective countries. Depending on the case, some of which can be found in WIPO LEX, Member Profile - Laws, Treaties, and Judgments, Available at: https://wipolex.wipo.int/en/members(Accessed: August 31, 2022); GUZMÁN, Marcela et al., Presupuestos para el Desarrollo en América Latina. Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo, 2014, p. 151-198, Available for consultation via the internet at the following page: https://publications.iadb.org/bitstream/handle/11319/466/Presupuestos%20para%20el%20desarrollo%20en%20Am%C3%A9rica%20Latina.pdf?sequence=1 (Accessed on: August 31, 2022). (*) Cuba and Venezuela are not considered in the comparison. (**) The Dominican Republic is not considered in the study either, however, it contemplates a medium level of development, which, compared to those evaluated in the scheme, could reach an initial to medium level of implementation for GARCÍA, Roberto. and GARCÍA, Mauricio, La gestión para resultados en el desarrollo. Avances y desafíos en América Latina y el Caribe, Washington, D.C. BID, 2010, p. 3-190, Available at: https://indesvirtual.iadb.org/file.php/349/modulos/La_gestion_para_resultados_en_el_desarrollo.pdf (Accessed on: August 31, 2022).; INDEX OF LAW, World Justice Project (WJP), Available at: https://worldjusticeproject.org/our-work/research-and-data(Accessed: August 31, 2022). This is a quantitative assessment tool designed by World Justice Project to provide a detailed and comprehensive picture of the extent to which countries adhere to the rule of law in practice in 2016 and 2021.

Correlatively, combining the document presented by the Inter-American Development Bank and the perception of justice evaluated in the Index of Law, in comparison to two strictly comparable periods, we can verify that a large part of the countries that have a medium and advanced level of implementation between the countries that carry out an annual budget, in turn, have a perception of justice above the average (for the year 2021 it was 0.49), but they have had a setback compared to themselves when comparing the year 2016 with 2021 by sharing the same methodology, while the large conglomerate of countries with a fixed budget have, for the most part, initial implementation with a perception of fairness below the average, but at the same time a setback in terms of perception of fairness between comparable years, where four of the eight countries have had a retreat, while the others have remained the same.

3 FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The results obtained from the respective identifications derived from the regressive diachronies presented and the shared comparisons must be taken with moderation since, although a clear relationship can be observed, the danger is to generate a cognitive dissonance of correlation that does not necessarily imply causality17. Therefore, the results of an exploratory nature give us an idea of where we place the indicated judicial institutions, their institutional relationship with the budgetary dimension and the cognitive integrations to understand these elements from the perspective of management by results, especially before the elements of State of Law that have been shown to contextualize, that although they are not unique, they give us a kaleidoscopic idea of the relationship for the understanding of the development of judicial institutions.

With what has been shown to date, the paradox that implies having a guaranteed budget and generating few incentives to implement a results-based methodology is confirmed, is reflected in a perception of justice that is the same or in decline, while for countries with annual budgeting the perception of fairness for the years of verification was mostly higher than the average for the region, there was setback but in turn there were three countries with progress with respect to their respective comparability.

However, it is no less noticeable how there is a setback in the region and the paradoxes regarding fixed budget and annual budget, remain in accordance with the perspective of measuring the capacity of budgets for development generated by results. Despite the fact that there may be progress in the institutionalization of the elements observed, what is worrying is observing that there has been a setback in the perception of the Rule of Law that exists in the region, since there are few countries evaluated that have progress after the elapsed time threshold. Despite this, this approach adds to contribute to the mosaic of empirical research on the performance of the justice system by identifying and analyzing the behavior of judicial institutions related to their budgetary function in particular, quantitatively with respect to their progress in relation to considerations of the Rule of Law and qualitatively with respect to the qualification related to the perception of the judicial institution in general.