Summary: 1. Introduction; 2. Theoretical Reference; 3. Methodology; 4. Data Presentation and Analysis; 5. Closing Remarks; 6. References.

Sumário: 1. Introdução; 2. Referencial teórico; 3. Metodologia; 4. Apresentação dos dados e análise; 5. Considerações finais; 6. Referências.

1 INTRODUCTION

From the perspective of the Economic Analysis of Law, the members of the Judiciary must consider the possible consequences of their decisions, not only under the strictly legal approach, but also due to the significant impact on economic life and social.

The referred theory understands that consumers and airlines are rational and look for the future, taking into account their private costs and benefits3. The objective of both is to maximize their benefits at the lowest possible cost.

In this context, the present article asks: Do facilitated access to justice, low litigation costs and the amount of compensation arbitrated in lawsuits influence consumer behavior in the context of repetitive litigation under the approach of the Economic Analysis of Law? The hypothesis is that facilitated access to justice, low costs of litigation and arbitrated damages in lawsuits influence consumer behavior in the context of repetitive litigation in the airline industry.

In the scenario of excessive litigation4, the growing numbers of repetitive demands seem to point to a problem related to cost fixing lower than the advantages to be obtained if people choose to take the decision to sue.

From this question, the study presents the theoretical and conceptual aspects of economic analysis of law, contextualizing them within the scope of civil liability in the sector airline, to try to understand whether the repeated claims against airlines are related to the marginal costs of a process (costs of the parties, and legal norms) against marginal benefits (estimate of the indemnity to be achieved).

As for the objectives, the present research is descriptive-exploratory. It is descriptive because it describes the phenomenon of increasing judicialization of the airline industry, based on data secondary data obtained from legal norms and data already available in official bodies and private organizations, to investigate changes in behavior in a longitudinal from the CDC edition and the aerial blackout. It is exploratory because it seeks to know the varied nuances between the legal system and judicial decisions on behavior of consumers and airlines through the discussion of the phenomenon, under the lens of the Analysis Economics of Law, exploring the correlations of costs and benefits of judicialization of conflicts.

For the treatment of the judicialization of the air sector in Brazil, the interpretation of the data indicates the need to change the existing incentives, for example, modification of the system of procedural costs and the jurisprudence that currently admits compensation for moral damages for any situation inherent to air transport.

2 THEORETICAL REFERENCE

From the studies of Ronald Coase, Guido Calabresi, Henry Manne, Gary Becker and Richard Posner, among other authors, the Economic Analysis of Law has become an academic discipline.

According to the Economic Analysis of Law, the decisions of economic agents, individuals and/or companies are based on the cost-benefit binomial, according to the set of available information at the time of assessment and in the context of your preferences translated into a level of well-being5.

According to Posner6, Law and Economics maintain an intrinsic and permanent relationship in a management perspective whose objective of legal norms, institutions and judicial decisions is to promote efficiency, which implies the maximization of well-being social.

In this perspective, the Economic Analysis of Law starts from the premise that individuals are rational and look to the future, taking into account their private costs and benefits. The objective of individuals and/or companies is to maximize their benefits at the lowest possible cost, using all available information in their decision-making process7.

In this way, the Economic Analysis of Law goes beyond the dogmatic analysis of the sources of law and the traditional academic rhetoric of interpretation and application of law, and uses economic and behavioral theory to discuss and analyze the reality of the influence of the legal system and judicial decisions on the economic and social life.

The Economic Analysis of Law is divided into two perspectives: the descriptive and the normative:

From a descriptive point of view, Economic Analysis of Law is concerned with the effects of a given standard. The concern here is to predict how people will behave under a certain norm and what will be the resulting effects. From the normative point of view, attention turns to the degree of social desirability of a specific norm. It is a way of evaluating the efficiency of social policies drawn by the standard. (Shavell, 2004, p. 1-2)8

Starting from the premise that human behavior is always a response to incentives, legal norms, as they are endowed with sanctions or rewards, influence the behavior of individuals and/or companies in some way. Therefore, science economic is appropriated by the descriptive for the empirical construction of models for predicting the behavior of agents, from the analysis of legal norms and the reaction of agents to the changes in laws or their application.

The normative reminds that the legal system is defined in the Democratic State of Law by the representatives of the people. In this way, the normative seeks to promote efficiency in terms of economic objectives, through legislative changes or public policy recommendations that increase well-being.

As it is a useful legal analysis tool, both the descriptive and normative perspectives serve the purpose of the present. The descriptive because it allows the formulation of possible correlations of the legal system and judicial decisions on the behavior of consumers and airlines, when faced with the growing and repetitive judicialization. The normative because it tests the efficiency of the norms, when confronted in the implementation of the values and rights materialized in the Federal Constitution and in the infra-constitutional legislation, including in the debate, the Code of Consumer Defense and the Code of Civil Procedure.

3 METHODOLOGY

This study was designed from the research of the theoretical-conceptual framework, already presented in the previous section in which the main economic premises of the Economic Analysis of Law were revisited, with emphasis on the maximization of wealth developed by Posner9 and on the function of well-being developed by Kaplow and Shavell10.

To answer the problem, as it is a multidisciplinary method11, the Economic Analysis of Law was used in the present methodology to understand how the sector's stakeholders behave in the face of legal incentives and judicial decisions.

The other secondary data, such as electronic books, laws, scientific articles, theses and dissertations, were found in the databases of virtual platforms12 and on the websites of public agencies and private companies.

The search was performed using the keywords: “air sector”; “repetitive demands”; “economic analysis of law”; “impact of laws and judicial decisions”.

The main sources of evidence selected were: (i) the Brazilian Federal Constitution and infra-constitutional laws, such as the Consumer Defense Code and the Civil Procedure Code; (ii) economic data on judgments/judicial decisions rendered in claims for damages against airlines; (iii) data collected from websites of lawtechs, associations, private companies and the ANC regulatory agency.

The selection of secondary data was guided by triangulation and internal coherence, and the researcher's simple economic intuitions in view of the notorious and indisputable high number of lawsuits pending in the national judiciary13.

As a methodological strategy, triangulation allowed the selection of data through independent sources14 that apparently did not communicate.

However, these different sources of evidence, when analyzed based on the theory and method of economic and behavioral analysis, contributed to the researcher's reflexivity, defined as that in which conclusions are reached “through the increase of cross-controls and the use of principles of a critical technique that makes it possible to closely monitor the factors that can bias a research”15, and not based on previous ideologies, impressions and intuitions16.

Although the limitation of the universe of available data cannot be denied, this method had the advantage of avoiding the elaboration of complex calculations that would make the production of the article unfeasible.

In addition, the method employed does not intend to exhaust all possible regulatory and judicial incentives that contribute to the increasing judicialization of the airline sector over these years.

4 DATA PRESENTATION AND ANALYSIS

Article 5 of the Federal Constitution, in its items XXXII and XXX prescribes that it is up to the State to promote consumer protection, and to the Judiciary to assess any injury or threat to the right17.

In compliance with the Constitution, the enactment of the Consumer Defense Code took place, which, since the 1990s, had a profound impact on consumer relations between consumers and providers or suppliers of products and/or services.

Since the enactment of the Code, civil liability in consumer relations is no longer based exclusively on fault and has become objective, except in exceptional cases provided for in the Consumer Defense Code.

In this regard, special attention must be paid to liability for the fact of the product and service, provided for in article 14 of the Consumer Protection Code18, in line with the obligation to indemnify arising from the practice of an illicit act19.

Using the Economic Analysis of Law, it is clear that the CDC promoted a new legal framework in which consumers, disrespected in their rights, became increasingly aware and informed and began to look for consumer protection and defense agencies. or directly to the Judiciary to resolve their conflicts.

So much so that only in 2021, according to the Annual Monitoring Bulletin of Consumidor.gov.br - Transporte Aéreo20, the National Civil Aviation Agency (ANAC) recorded a 58.1% increase in complaints compared to the previous measurement and, for each 100 thousand passengers transported, complaints increased 22.3% against Brazilian airlines and, for foreign airlines, 57.3% (Table 1).

It is interesting to note that throughout 2021, the most common complaints registered on the consumer.gov.br platform, as an ANAC channel, were related to reimbursement (31.9% of complaints), offer and purchase (24.8%) and change by the passenger (19.3%). The bulletin21 also reports five other most common sub-themes among Brazilian and foreign companies.

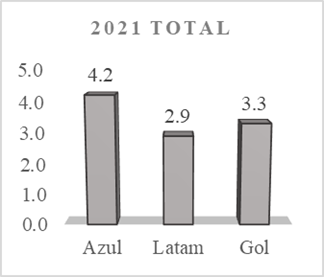

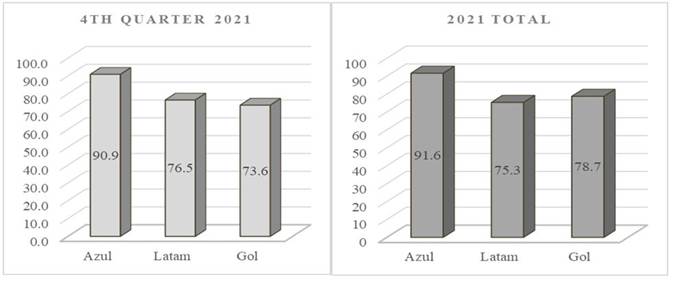

ANAC's monitoring bulletin for the year 2021 also presents solution rates, satisfaction rates, average response time and main sub-themes complained about, according to graphs extracted from the platform (Figures 1 and 2).

As for satisfaction and, especially, resolution rates, data from the consumer.gov.br and Anac platform indicate that at least a quarter of complaints are not resolved by alternative means of conflict resolution22.

Data from the consumer.gov.br platform reveal another finding: the main complaints do not cover most of the matters brought to the judiciary, which will be explained below.

As highlighted, in recent years, the Courts are frequently called upon to resolve claims for compensation for moral damages resulting from delays and/or cancellations, overbooking, loss or loss of luggage, among others.

According to information from the National Council of Justice23,

“in Brazil there is, on average, one lawsuit for every 227 passengers transported in 2019. There are eight cases for every 100 flights”.

According to the International Air Transport Association (IATA)24, Brazil has the largest number of lawsuits against airlines and shows that, in recent years, 2.3% of the total cost of Brazilian airlines includes the payment of compensation for lawsuits lawsuits.

From the point of view of the Economic Analysis of Law, the inexorability of the Judiciary

“has a clear objective: to reduce social costs that, without the State offering the judicial activity, would be much higher. In other words, jurisdictional activity only exists because without it, society would be much worse off than with it”25.

From a legal point of view, the “State has the duty to provide the judicial protection promised by the rights - trans-individual or individual”26.

According to Dinarmarco27, the objective of the inexorability of jurisdiction is social pacification.

It happens that the overuse of the Judiciary, like any common good, ends up compromising the idea of efficiency of the judicial activity itself. The lower the efficiency, the greater the practice of illicit acts. In Erik Navarro Wolkart's reading:

When this occurs, the social cost of using justice rises excessively, basically meaning that: (i) the constitutionally guaranteed system becomes slow and inefficient, like an avenue congested by vehicles that do not leave the place; (ii) as this system is subsidized by taxes, it is society that bears these costs. (Workart, 2020, p. 313)28

This inefficiency falls on the parties to the processes that do not reach a fair and effective resolution of the conflict within a reasonable period of time, and on society that bears the financial and social costs of the ineffective justice system. Justice, like any service, has the capacity to handle thousands of lawsuits filed annually.

Luciano Das Ros and Matthew M. Taylor29, when opening the black box of the judicial system after three decades of reform, concluded that the Judiciary costs a lot, which confirms the phenomenon of collectivization of negative externalities of its overuse. The costs are not just financial, as they compromise 1.3% of GDP30, but unfortunately, reflect the small percentage of 21% of the population that considers justice to be great or good, compared to 35% that evaluate it. as bad or very bad31.

The constitutional framework and the CDC, thus, confirm one of the premises of the economic theory of law that the legal system can influence the decisions of economic agents, directing behavior from the creation of incentives or disincentives.

In addition to the Civil Procedure Code, other incentives in the justice system, as opposed to preventing and facilitating the attainment of fair and effective protections, seem to contribute to the growing and continuous litigation.

The ease of access to justice, the costs of the process and judicial decisions are also highlighted as incentives for judicialization.

As of the October 2006 blackout, at the suggestion of the National Council of Justice32, the Federal Courts of Justice and Regional Courts created the Special Civil Courts in the main airports in the country, aiming to deal with the causes of overbooking, delays and cancellations of flights, loss and loss of tickets, food, accommodation and transfer of passengers waiting for the next flight, among others.

The service provided by the Special Civil Courts at airports is free of charge without the need for a lawyer. The scope is to facilitate access to the judiciary, through gratuity and simplicity, based on the initiative of the citizen-consumer, seeking to resolve the conflict quickly through conciliation and transaction33.

The concept addressed the various problems arising from the air blackout, but after more than fifteen years, both the Courts and the Courts of Brazil are crammed with lawsuits, with compensation for moral damages in consumer relations reaching the second place (3.15%) among the most recurrent subjects of the State Courts34.

Although the Courts remain in full operation at the main airports in the country, among consumers, the allegation persists that their rights are repeatedly disrespected, while airlines, in turn, offer resistance to reparation or compensation for moral damages, supporting them. on several arguments, among which the access to justice, facilitated by free justice and low litigation costs, and the moral damage industry, exacerbated by the emergence of lawtechs35.

A simple internet search is enough to find pages of the so-called “flight compensation companies”. Names such as AirHelp36, Liberfly37 and Resolvvi38 are active in the field of aerial compensation, through the filing of virtual processes.

Companies like AirHelp ask:

“Have any of your flights been canceled or delayed? Get up to $10,000 per passenger for flights within the last 3 years. Whatever the fare is from all airlines, all countries and if you don't win, you don't pay”. Resolvvi announces Resolvvi announces: “Claiming your rights is super simple. Who knew it would be so easy? Find out your rights and receive up to $10 thousand. Start free”.

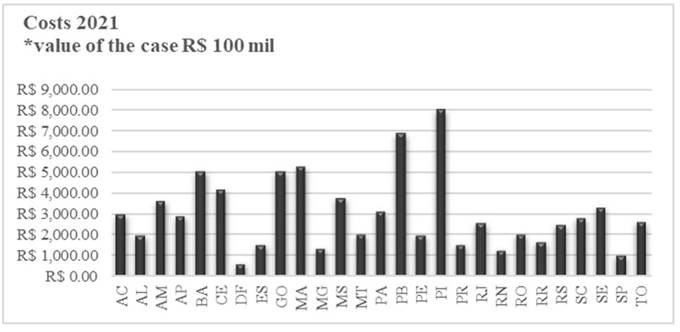

In addition, the benefit of free justice and the low cost of court costs indicate that the parties prioritize litigation over self-composition of the conflict. By way of comparison, even after the readjustments in some courts, the costs of the TJSP, when compared to the other State Courts, are in the last positions of the rank39, as shown in the graph below:

Thus, in a very simple model, except in cases of granting of free justice, assuming that the damages reach the minimum level of R$ 10,000.00 - as announced by lawtechs - and taking as a basis the judicial fee of the TJSP of 1% on the value of the cause at the time of distribution or, in this case, the minimum value of 5 UFEP(s), which corresponds to R$ 159.85 and, for postal summons, the value of R$ 27.1040, one realizes that the procedural costs paid by the parties are far from covering all the costs of the lawsuit.

Considering that the judgments in the State Courts, as will be highlighted below, are mostly favorable to consumers, whether in the event of total or partial success. When you think about each type of process, filed individually by each passenger, you can see that the social benefits are minimal. If the objective of the jurisdiction is to achieve the promotion of well-being, under the lens of Economic Analysis of Law, there is, in this simple model, a dysfunction between what is understood by social and private well-being in the filing of lawsuits of the airline sector, if there were no legal incentives, such as the low costs of the process.

This is not to deny the individual access to the Judiciary for the protection of rights. Some claims arising from failures in the transportation of people by air are absolutely essential. Who has not heard about the case of the mother and the child with autistic spectrum expelled from a flight or the passenger's dog that disappeared for days in Guarulhos Airport? The pain experienced by such consumers is indisputable. But, when it comes to negative externalities to the judicial process, the filing of thousands of claims, for any cause of action, is absolutely counterproductive to accessing justice at affordable prices.

As can be seen in the model presented, the State subsidizes the demand for services and, those who use this service transfer the bill to the rest of society, but does not transfer the benefit earned by the compensation that is appropriated only by him and his patron. Moreover, the repetitive and growing litigiousness of the airline industry increases the rate of congestion in a systemic way, that is, it creates a backlog of cases not judged throughout the year in the entire judicial system, an index that is well known in the CNJ's Justice in Numbers Report.

From an economic perspective, according to economic analysis websites such as Agenciainfra and Valordaaviação, because these are publicly traded companies with shares on Bovespa, it is estimated that the cost of judicialization in the airline industry is R$ 1 billion per year, contributing to the increase in ticket prices borne by society.

In the airlines' financial statements, judicialization costs are included in operating expenses/revenues and are easily found in the quarterly balance sheets regularly published by the major Brazilian airlines41/42/43. These costs, in the end, are shared by society, which will pay for more expensive tickets.

Regarding judicial decisions, the jurisprudence understands that in consumer relations, the supplier's responsibility is objective, and it is up to him to demonstrate, in order to exempt himself from liability, the inexistence of defect, exclusive fault of the consumer/third party under the terms of article 14 of the CDC or Act of God and force majeure. If there is no proof, it is understood by the breach of obligation provided in art. 737 of the Civil Code, according to which it is the duty of the carrier / supplier to comply with the schedules provided in the contract, resulting in damage in re ipsa, releasing the consumer from the effective compensation.

Applying the normative Economic Analysis of Law in the specific hypothesis of moral damage in re ipsa, the analysis parameter cannot be deviated by moral or philosophical conceptions exclusively linked to the abstract principle of justice44. For Wolkart45,

“Many choices founded on fainess end up seeking the concretization of those principles at the expense of social welfare, which would be unjustifiable” (p. 150).

It is not about creating a defensive jurisprudence, but to reestablish new criteria in which the moral damage can be presumed as a result of the mere delay and eventual discomfort, distress and inconvenience suffered by passengers in air transport46.

This is because several other factors must be considered in order to investigate the actual occurrence of moral damage, requiring, therefore, proof by the passenger-consumer of the extra patrimonial damage suffered.

Undoubtedly, the circumstances of the concrete case will serve as a reference for the possible proof and consequent verification of the occurrence of moral damage, for example: i) the verification of the time it took to solve the problem, that is, the real duration of the damage; ii) if the airline offered alternatives in order to better serve the passengers; iii) if clear and precise information was provided in time and manner by the airline in order to mitigate the discomfort inherent to the occasion; iv) if material support was offered (food, lodging, etc.) when the delay was considerable; v) if, due to the delay, the passenger ended up missing an appointment at the destination, among others. ) when the delay is considerable; v) if the passenger, due to the delay of the aircraft, ended up missing an unavoidable appointment at the destination47, among others.

In this case, where no extraordinary fact has been invoked that has offended the core of the consumer-passenger's personality, there is no way to speak of moral damage for compensation.

5 CLOSING REMARKS

Based on the analysis of the data presented and from the point of view of the Economic Analysis of Law, the new rights assured by the CDC, the easy access to the Judiciary through the operation of the Special Courts, including in airports, the emergence of lawtechs, the low procedural costs in the States where the main airports are concentrated, and the jurisprudential understanding about moral damage in re ipsa, constitute natural incentives of the justice system that induce consumers to seek their own utilities (personal benefits) without collaborating with the maintenance of the good (Justice) for other citizens.

Although this is a complex problem, it is necessary to develop mechanisms or change incentives that currently contribute to the uncontrolled use of justice by consumers and airlines and, consequently, to the exhaustion of the Judiciary, to the detriment of society as a whole.

In this scenario, it is evident that the law and judicial decisions, the first as a normative instrument and, the second as a guide to the activity of the main subjects of the air sector, can and should contribute to the reestablishment of social welfare in this segment of the economy. The solutions go through different interventions, which is why this study does not intend to exhaust the broad debate, often permeated by ideological biases, on the most efficient normative designs or, socially desirable, for the correction of dysfunctions in the Brazilian airline sector.

Certainly, new research focusing on simple and already established economic models, such as game theory, the Nash equilibrium, the agency problem and sunk costs, will be able to identify and deepen the analysis of the prevailing incentives in the growing repetitive litigation in the airline industry.

It is not intended here to present a definitive answer to the problem, but to use the approach of economic analysis as a theory and method, to understand the increasing and repetitive judicialization of the airline sector.

In any case, the interpretation of the data indicates that the treatment for the growing volume of repetitive claims in the airline industry passes through, for example, the modification of the procedural costs system and the jurisprudence that currently admits compensation for moral damages for any situation inherent to air transportation. Without changes in the existing incentives, judicialization will remain a difficult turbulence to overcome.