1. Introduction

We can easily determine that our experience of the world is very subjective. We don’t see things as they are, but rather as we are (origin unknown). When it comes to human beings, it is very hard to quantify or typify ideologies, sensations, or feelings. But to make our lives easier and give us a small sense of control, we try to typify every context within a set of socio-cultural norms, in any given period of history. The way we see the world and our perception always ends up being influenced by the moments we are living and that reflects in every level of our understanding of the world. Of course, these issues are reflected in every problematic we have as a society, and issues like gender, identity and gender expression, are highly polarizing. Mostly because these are the ones we can’t typify.

In more recent years, we are witnessing a widening of the gender spectrum and what that means for an increasingly growing number of people. This is something that starts as early as childhood and generally speaking, it would appear that we are witnessing a rather unprecedented time of gender fluidity, when the so-called “traditional expectations” of what each, men and women, are supposed to wear is blended (Sanders, 2019 n.p.) [1]. Unfortunately that’s not entirely the case, even though brands, designers, celebrities and influencers are approaching the issue and bringing awareness to this more-than-ever political and social experience of the world, there’s still a lack of communication and sensitivity that comes with living in a society that majorly does not accept you as who you are. Weingarten (2015 n.p.) [2] writes about the influence of genders fading, and how a growing population of the millennial generation feels like gender shouldn’t define us, at least the way it did historically. Ideally, a person should not feel pressured into conforming to traditional gender roles and/or behaviors.

Kate Bornstein, a gender theorist says that “if there’s a leading edge that is the future of gender, it’s going to be one that understands gender is relative to context” (Weingarten, 2015 n.p.) [2]. This only comes to show that gender is stipulated by society, history, economy, and in the same way it is a construction and result of these factors, it can also be deconstructed and seen in a different light. If we associate today’s context with gender, then we have to challenge it. The curtain has fallen on the stringent association of sex, gender and identity; they can influence each other, but they can also stand on their own. One of the issues with the gender fluidity reality is that people feel a level of comfort in the typologies we know today. It becomes easy to fall into the traditional roles, they provide a certain comfort and stability, especially in a world that can be hard to decipher.

But it’s even a younger generation of fashion consumers that are driving demand. Ashley (2021 n.p.) [3] says “56% of Gen Z consumers identify as “neutral” on the gender identity spectrum and already shop outside their gender”. Generation Z consumers will account for $143 billion in spending in the coming years (Ashley, 2021) [3], which from a marketing perspective, bears a heavy weight and one of the ways that the industry might start to make this change is, indeed, through marketing and communication.

2. Literature Review

We can start by stating that a garment, a piece of clothing, fabric, textile, has absolutely no gender. Every and any attribution we make is purely fabricated, but for one reason or another, fashion has always been defined by codes, seasons, shows, trends and existed under the assumption that gender functions in a binary. Many in the fashion industry have started to see and work upon this fractured system, but there’s one question we need to ask; how can the spectrum of gender be represented in a way that reflects everyday life?

Fung (2021, n.p.) [4] tells us that “being non-binary is not a “third gender”, but a stance and viewpoint that gender is a spectrum”, which means that part of the discussion is tapping into the social and cultural aspects of gender, of what it feels like to live outside the binary. If fashion indeed is representative of the state of the world, then it must represent all the variants of it, not just the ones that feel convenient in time and space. Susan Kaiser (2012) [5] poignantly points out that fashion changes with each person’s visual and material interpretation of who they are. But also, fashion resides within a system of economic, cultural and financial norms that make it harder to break away. It’s a polarized stance, because on one hand, it’s crucial and vital to let everyone be who they feel they are, but on the other hand, society makes it hard to, when all we see is a representation of a small part of a (westernized, binary, white and heterosexual) population. Communication and representation are key. If children don’t see themselves represented in the mainstream media, how will they ever find a way to express and be themselves?

Wortham (2018) [6] writes about sociologist Helana Darwin, who began researching non-binary identities back in 2014. One of her most important findings was the role social media played in people’s lives, especially for those who found themselves geographically isolated from other non-binary people. There’s a sort of democratization of space, voice and experience that platforms like Twitter and Instagram allow, people are no longer confined to their own rooms, cities or communities, but they are able to find their own. Darwin’s research describes social media as a “gathering place for discussing the logistics of gender” (Wortham, 2018, n.p.) [6] and where people find support, reassurance and interact with similar experiences to their own. Beyond the ups and downs, one thing becomes abundantly clear with the non-binary community: fashion is key. It’s a way people choose to express their identity and represent what they feel. From our earliest moments, clothes equate definition and for ALOK Vaid-Menon, a gender non-conforming writer and performance artist, it’s vital to recruit a bigger diversity of genders, sizes, abilities and ethnicities, in runway shows, campaigns (Chen, 2019, n.p.) [7] and even rooms where decisions get made. Fashion is also political, and the first impression we have of someone is strongly based on the clothes they wear and their gender identity (Sprayregen, 2019, n.p.) [8], but if we think of media formats, the images we see perpetuate unrealistic, stereotyped and limited perceptions of reality. There is indeed a social structure put in place of traditions, institutions, moral codes and an established supposed way of doing things that is so deeply embedded in the media that ends up affecting and exerting power over populations, societies and communities. But knowing that structure also means that we can change it, especially when we start to create in different ways (Gauntlett, 2008) [9]. An entire life of being exposed to the same images of the same people over and over ends up shaping our choices, thoughts and behaviors from a very early stage of life. If we start to include a more diverse perspective of dialogues and realities, we appeal to different kinds of audiences, instead of a singular one.

Ashley (2021, n.p.) [3] writes that marketers assume that the mainstream approach to the world is what sells and reaches more. But by combining the marginalized identifiers, you would be inviting an even bigger share of the market to consume your products, services and brands. But to do it, you don’t just need the perfect product, service or brand; you need a combination of all, culminating in the appropriate communication strategy. It doesn’t necessarily matter if the product is designed for non-binary people, it matters that they are part of the conversation; that the product takes into account their lifestyle and reality; and that it communicates exactly that.

There is a rise in gender neutral, unisex, genderless brands, but most of these brands should not be wearing that “label” as a way of being provocative or exciting, trendy or contemporary, unless they are talking about the issues that really matter to a non-binary lifestyle (Sanders, 2019, n.p.) [1]. The reality isn’t always fabulous, and brands need to tap into the social aspects of it; like how people navigate a store, or how they feel going into a website and being compartmentalized into binaries; browsing through social media accounts and realizing cis-straight-white people are the majority, if not the totality of representation; or how people on the streets, at work, at home react to how they choose to express themselves. There is indeed a gap between what categorizes a genderless brand and how it translates into reality, and that’s what we need to tap into.

The problematic, like it was said before, lies in representation and communication. Brands, products and services are designed to appeal to the stereotypical binary, and end up ingrained with a certain gender image of what is masculine and/or feminine (Sultana & Shahriar, 2017) [10], a sort of framework to build brand identities and associate them with one or another. There are, of course, disruptors and key-players that are challenging the norm and shifting the current paradigm, but still see the distinction. Millennials and Gen Z’ers are gaining more and more purchase power, which means we are becoming the biggest consumer generation, but not without conditions. According to the Deloitte Global 2021 Millennial and Gen Z Survey, Millennials and Gen Z’ers are not passive consumers and put their wallets where their morals are. Both generations value relationships with companies that care about the environment, are concerned with their personal data, and have positioned themselves on social and political issues. And gender fluidity is a social and political issue that we want to see tackled.

Research has shown that there are benefits in moving towards a more gender-neutral communication route (Sultana & Shahriar, 2017) [10]. The younger generations seek out inclusiveness and equality as a way of finding their own ways of expression and individuality. Gender neutrality can be a path to be whomever you want without judgment, and brands, products and services have to start reflecting that. People want to externalize their feelings and they want to see themselves represented in their cultures, societies and communities. Especially in the age of social media when it’s as easy as a type-and-click to bring down a campaign (https://www.designalytics.com/insights/unisex-sells-the-rise-of-gender-neutral-packaging). A Mintel study on Generation Z, from 2019, [11] suggests that brands that focus on this particular problem being solved, instead of the audience they are approaching, can have a higher rate of success in projecting gender-neutrality and what this means is that a brand that focuses on a long term strategy to include gender neutral language, image and messages can have a bigger impact than those just trying to catch the zeitgeist and a fleeing audience.

Back in 2016, Zara fell under that spell and launched a capsule collection called “Ungendered” which featured 16 pieces of neutral design and colors. On one hand, it seems like a great approach to accept more diverse forms of gender expression; but on the other, it might be that they were appropriating what we can call a masculine style and applying it to all genders. In this case, erasing the femme identities and perpetuating the stigma that masculine fits all, but feminine is only acceptable for a limited scope of identities (Sciacca, 2016) [12]. What lacks from Zara, and other brands that try to play the genderless card, is the contextualization of everyday life for non-binary folks. As Sultana & Shahriar (2017) [10] found in their study, gender ambiguity is becoming the new marketing norm. Stella McCartney created and launched her first gender-inclusive collection called Shared. She talks about appealing to a younger generation and how “they inclusively celebrate individuality and diversity, and are using their self-expression to affect social change” (Kay, 2020, n.p.) [13]. But, if we go into her website, there is still a distinction of categories at the top navigation; there’s Women, Handbags, Unisex, and so on (Fig. 1). And while her brand’s intentions are in the right place, it falls short on representing a non-binary existence. The models on the Unisex category are still clearly male and female, which for someone who’s not on the binary spectrum might not be a thrill to see. According to Ashley (2021, n.p.) [3] terms like unisex in brand messages are shifting and feel outdated and not representative of the non-binary, pointing out that there’s a need to culturally change the terms to fluid or neutral.

If the industry rethinks these gender designations, that we know historically categorize fashion, both established and new brands gain an opportunity to reach more people, and consequently, consumers. On a different side of the spectrum, Levi’s might be one brand leading other fashion industry players with their Unlabeled collection, launched in 2020. After doing market research, Levi’s found that 30% of their Gen Z’ers fans shop across genders, and it showed them that there wasn’t a genderless concept in place, which meant they were missing a mark. In an attempt to fix that, Levi’s put together a group of their LGBTIA+ employees to curate a genderless collection from their existing line (Fig. 2).

Fig.2 The Levi’s Unlabeled Collection. Source: https://www.levi.com/GB/en_GB/curated-by-unlabeled/c/levi_collections_unlabeled_curated

Strategies like these are what makes the difference between brands who are adapting long-term, getting other people involved in the conversation and actually making them part of the message, image and communication.

3. Method

To understand this issue better, we decided to develop an exploratory questionnaire that focuses exactly on the perception of genderless fashion in the mainstream audience. “Questionnaires are survey instruments designed for collecting self-report information from people about their characteristics, thoughts, feelings, perceptions, behaviors, or attitudes, typically in written form” (Martin & Hanington, 2012, p. 140) [14]. They are fairly simple to produce and deliver, but it’s always important to pay attention to the language used - especially with such a sensitive and personal topic.

The questionnaire was composed of 34 questions with a mix of closed and open-ended questions. Again, being of such personal nature, it’s important to make use of open-ended questions that “provide opportunity for depth of response” (Martin & Hanington, 2012, p.140) [14]. In this particular case, the answers provided make it possible to trace a clear definition of what the 417 participants think about fashion and gender.

It’s important to understand the benefits and limitations of such methods before divulging and discussing the results, mainly because every method has its set of constraints. Questionnaires can be of a very simple nature but can also become heavy; in this case, the questions were built in a way that tried to bring easiness into the issue; it was important to start by asking a set of more general questions to then get a little more personal. They can be quite limiting, since close-ended questions offer a limited number of answers to which the respondent may not find themselves reflected in. On the other hand, open ended questions can pose the mentioned heaviness, because some people might not want to justify their answers with a longer format, or just don’t want to be bothered to write. It’s a great way to categorize the participants and chart their answers; but it might feel like the results are putting them into boxes, which is the opposite of our intention.

With any exploratory method, and even though the questionnaires are totally anonymous, some people might feel compelled to answer the politically correct way and avoid disclosing their real feelings towards such a personal issue. It’s one thing to ask someone what they think of a social or cultural movement, phenomenon, issue; and a different thing to how someone acts and feels. The results have to be analyzed with a grain of salt and put into perspective of how most people think they should answer. This is not to say that politically correctness erases the importance of the results of such exploratory method, but it definitely takes a slice of the percentage of their scientific relevance.

4. Results and Discussion

Because of the aforementioned open-ended questions, the results were unexpected and unpredictable, but we had a total of 417 respondents as of October 12th of 2021, which is a greatly extensive sample for this study and the insights are highly valuable for our paper. It’s important to understand that the limitations may carry some weight, but are not determinative for what is considered a very successful study.

On the very first question 64.7% of the participants, when asked which of the following statements do you consider to be true, answered that gender is a sensation and a feeling of self, masculine/feminine/none/all (Fig. 3). A very positive affirmation and realization that the Millennials and Gen Z’ers (composing 57.4% and 30.3% of the respondents) are aware of the social conditioning that is the binary, meaning that it’s starting to be a part of the conversation.

Fig. 3 Infographic representation of the first question of the contextual questionnaire. Source: author

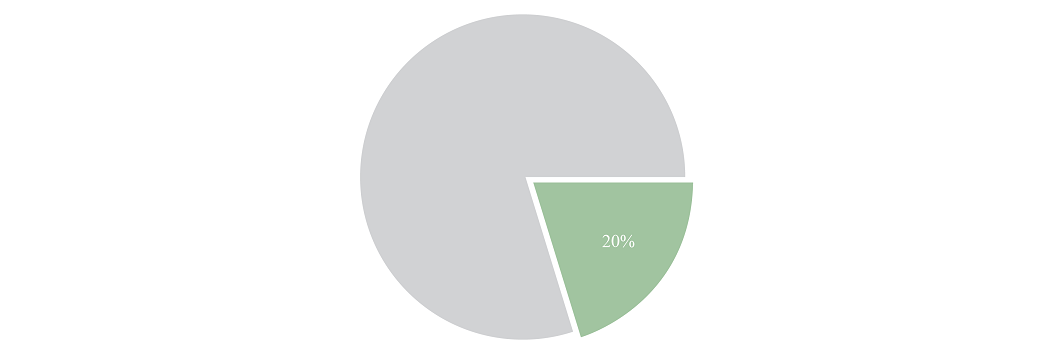

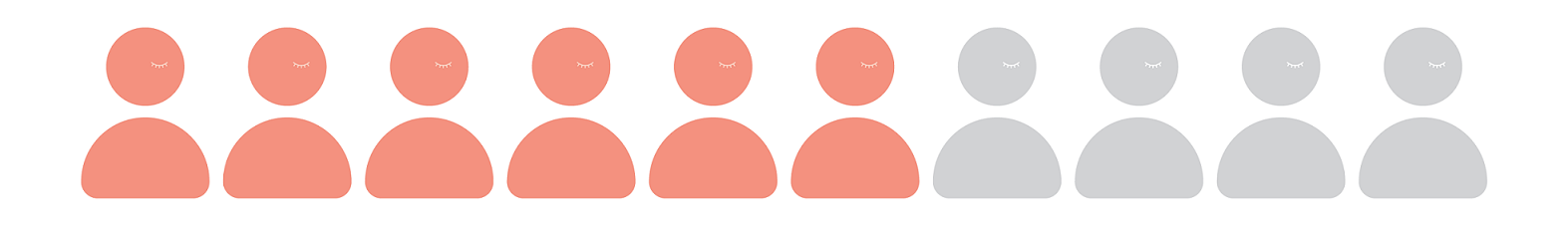

Our seventh question asks if the person identifies with a gender different than the one that was designated at birth, and 20% of the respondents said yes (Fig. 4), which is quite an interesting percentage. As Friedman (2017, n.p.) [15] writes, “for most Millennials, traditional gender classifications simply don’t work anymore”, indicating that indeed we are moving towards more diverse ways of feeling and expressing. Which brings us to another question, asking if gender plays a role in how the participants dress outside of work; 68.8% said no. And when asked why, with an open-ended question, the answers are extremely diverse, but all tend to say the same thing: the way I dress reflects how I feel and gender has no influence. Of course there’s a fair share of people who like to dress for their gender to feel confident or because it was taught to them the associations to femininity and/or masculinity. A few, very poignant answers, reflect the reality of non-binary people who want to dress differently than expected and won’t, because of someone else’s judgment. There’s a cry against convention in favor of a more tolerant, diverse and accepted (Dua, 2016) [16] lifestyle that comes with gender fluidity, and if brands start to tap into it and recognize, not only, how their products and services can be used, but also focus on the reality that comes with being non-binary (Friedman, 2017) [15], it starts to become mainstream.

Fig. 4 Infographic representation of the percentage of people who do not identify with the gender they were assigned at birth. Source: author

Especially when it comes to fashion, 59.7% of the respondents believe that fashion plays a big role in how they express themselves (Fig. 5), a way of communicating, whether it be personality, feelings, and most importantly, identity. One very interesting answer from a Millennial reads that “more and more, we are going towards a universe in which clothing/fashion is a way of expression that transcends gender and where wearing a skirt, for example, does not determine who you are but simply what you like to wear” (f.t.). If and when a brand taps into something like this and uses it as a manifesto, they can clearly target the generations that are becoming the future buyers with economic power, while aligning to the cultural movement in understanding how the lack of labels isn’t only a plus for society but also business (Friedman, 2017) [15].

Fig. 5 Infographic representation of the percentage of people who believe fashion plays an important role of how they express themselves outside of work. Source: author

Applied to the concept of genderless or fluid fashion, question twenty-four asks the participants why they think it makes sense, or not; a big percentage of the respondents focus on the designer and the brand and say they can make the clothes but don’t need to dictate who wears them (f.t.). Which in this context makes the most sense; apart from sizing issues, Max Kingery in conversation with Ashley (2021 n.p.) [3] says that developing gender neutral clothing makes logical sense for fashion brands, who are essentially producing one collection that ends up being more cost-effective. Even if we think in terms of sustainability and waste that is produced by the fashion industry - which is a whole other issue very much related to this topic but not analyzed in depth for this paper - this seems like a very important step forward. 75% of respondents agree that clothes should be worn by everyone in any context they see fit, which in its turn means that most of this sample agrees that in any capacity, the distinction of gender can become extinct.

This brings us to questions thirty and thirty-one that ask if participants know someone who fits in this non-binary reality. 33.1% of people said yes, which amounts to 136 people that know a non-binary person - this statistic is highly important because, even though it’s not the majority, it is indeed becoming more and more common to know someone who is non-binary. And when asked if they think fashion plays an important role in how they express themselves, most of the respondents said yes, justifying it as a way to tell society who they feel they are (Fig. 5). And last but definitely not least, we asked what advice participants had for someone who’s starting to develop a genderless brand; answers vary but say mostly not to make it all about basic colors, shapes and designs, that genderless is way more than a shapeless and neutral fit; a mix of feminine and masculine; cuts and shapes that fit a variety of people and bodies; defining the core values and concept; and most importantly, ask advice and involve non-binary people in the conversation and communication. One respondent said: communicate well that message and have values associated that demonstrate the daily actions of the team. And when it comes to the collections, do not limit yourself to squared and loose pieces, because genderless brands have a tendency to come to those shapes when they should be breaking stereotypes. Developing a genderless brand means wearing all sorts of colors, fabrics and forms (f.t.).

This comment is the bottom-line of any genderless or non-binary brand. Thus we can conclude it all comes down to communication and design; what this means is, genderless collections and brands need to be communicating to the realities of non-binary existences, instead of using the traditional and normative model that dominates the fashion industry. People seek out representation; people seek out themselves and want to see themselves in images, videos, talks, and not a variant of the same sort of binary constraints.

5. Conclusions

From the analysis of our contextual questionnaires and a fair amount of important and relevant authors, we can conclude that the challenge for brands looking to connect with people by tapping into gender fluidity can be twofold. It’s definitely not enough to recognize how your products and services are being used, but there’s also a need to reflect on the reality and context they are being used. Brands and designers (and maybe the entire fashion industry) need to craft a strategy that is effective and resonates with a lifestyle and not a gender (Friedman, 2017) [15].

In the age of social media, there is no fooling tech-savvy consumers who will research until the last drop of tweet. The younger generations have made it abundantly clear that consumer behavior is a function of personality and regardless of what attributes are being highlighted, these are what drive purchases; not gender, ethnicity, shape, size or age. Brands that would like to stay or become relevant have to tap into feelings, passions, character and go beyond the traditional demographic characteristics. In this particular case, they cannot call themselves genderless and still have (only) traditional binary categories in their websites; or shoot with traditional binary-looking models; or communicate within the norm without having done the work and including non-binary people and their realities.

When developing an effective brand strategy that is gender fluid, marketers should start by creating a muse or a personification of what the brand stands for and where brand’s values meet consumer’s aspirations. These aspirations should not be limited by gender but go beyond it, allowing brands to develop a voice that will resonate with an entire lifestyle, rather than being confined to limitations of gender. This can be harder for more established brands that already have their message crafted and know their consumer-base well; but for new, up and coming brands, it shouldn’t be hard to tailor to a variety of people. As it was said before, it all comes down to whom you decide to involve in the conversations, which can be enriching from an experience point of view. Admitting that you know nothing about a non-binary reality is the first step; educating yourself, talking to people, hearing their stories, getting to know their reality are other steps to follow. It can be hard to challenge the norm and what we are used to seeing and experiencing, but it can also raise important and relevant voices that can help someone struggling to find themselves and their own identity.

If we go online, the faces we see representing a non-binary existence are far more varied than mainstream culture (Fig. 6). To scroll through hashtags like #NonBinaryIsntWhite is to see a kaleidoscopic board of inspiration for a multitude of gender and ethnic expressions, with wildly varying styles of dress, makeup and settings (Wortham, 2018, n.p.) [6]. The entire point of doing this exercise is to see that there is no normativity, no need for people to limit themselves based on society’s ideals.

Fig. 6 Non-binary persons who post about their experiences on Instagram. From left to right: Jacob Tobia (@jacobtobia); Naveen Bhat (@namkeenaveen); Danez Smith (@danez_smif); and Akwaeke Emezi (@azemezi). Source: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/11/16/magazine/tech-design-instagram-gender.html?searchResultPosition=8

In the end, the emergence of brands, products, services and designers that challenge the binary norm is a way of staying and becoming relevant with the generations that are starting and going to be the future players in the economy. There’s no room for outdated assumptions or fake moralities, there’s just what you represent and how you choose to display that representation. And brands need to step up their game and refrain from using genderless as a label if their intentions of representing and talking to the everyday life and experiences of non-binary people is still blurred and misinterpreted.