1. Introduction

The design process is a complex, innovative and sophisticated process that involves multiple types of information integration. When developing for users, designers are required to take into account a range of factors, including but not limited to space, shape, image, light, colour, composition, and material. Furthermore, they must also address the emotional, social, and physiological complexities associated with the particular project. Experienced designers engage in design processes as a habitual and standardised procedure, characterised by unconscious stages or activities rooted in established design principles and practices (Mandala et al., 2018). However, junior design students often find it challenging to manage the design process, especially when dealing with their emotional changes as they learn to juggle multiple kinds of information and assess the relationships between them.

The challenge of designing for users with varying physical and physiological needs is even more significant for junior design students of the new generation. Therefore, it is crucial for junior design students to comprehend the physical, physiological, and emotional experiences of the majority of users, not just what is seen at face value. An understanding of emotional aspects can help them make decisions that lead to the safety and well-being of users. Although simulation techniques have been effective in the design profession, a few junior design students understand the emotional shifts throughout the design process. Before junior designers can understand the importance of emotional shifts, they need to know which emotions effectively affect the design process. Hence, it is imperative for design educators to devise strategies aimed at facilitating the cognitive and emotive development of novice design students while successfully integrating emotional transformations. Sensitivity to the guidelines of the simulation could facilitate emotion management abilities, thereby showing the influence of affective skills development on students. This paper aims to investigate the typical emotions that affect the design process and identify methods to enhance junior designers' skills in managing emotional changes. This study aims to explore the variability of human emotional regulation capabilities and assess the influence of emotional skill enhancement on students. The primary objective is to acquire a comprehensive understanding of these factors. These modifications clarify the objectives of the study and emphasise the significance of understanding emotional shifts in design students as they navigate their educational journey.

2.Exploring the intersection of cognitive thinking and emotional intelligence in design education

2.1 The role of cognitive architecture in enhancing design processes

The apparent ease with which experienced designers navigate the design process stems from their cognitive architecture. Researchers have shown that two kinds of memory work together in this architecture working memory and long-term memory (Ho & Siu, 2012). Working memory processes, the input and links new knowledge with the long-term stored knowledge, creating interconnected webs of knowledge known as schema. Through significant and connected schemata, experienced designers can function effectively, automatically, and in an organised manner by breaking down vast amounts of knowledge into limited working memory chunks. This is especially true for designing highly complex domains such as the elderly or physically handicapped people.

Effective cognitive thinking is critical in determining how efficiently learners studying complicated domains can learn. Studies have indicated that novice design students often rely on trial-and-error approaches, which quickly exhaust working memory and provide little room for developing new schema connections because they lack organised schemata (Smith et al., 2019). Three types of cognitive processing were: intrinsic processing, relevant processing, and tangential processing. Designing for the elderly is a challenge that calls for deep consideration of the task's inherent complexity, or ‘intrinsic thinking.’ And the brain's ability to form new schema connections depends on meaningful thinking. Research has shown that intrinsic reasoning is enhanced when emotional intelligence is integrated into learning processes (Jones & Brown, 2021). The term ‘extraneous thinking’ is used to describe mental processes that are not necessary for the completion of a task, such as daydreaming or ruminating. In complex design studies, elevated cognitive demands might consume working memory and hinder learning.

2.2 Cognitive thinking and emotions

In the context of intrinsic reasoning, the addition of affective abilities increases task complexity. Junior design students in design programs should apply empathy to get the user's perspective on the environment or product they are creating. With this newfound understanding, they can settle on the best course of action for the design (Walther et al., 2017). Developing empathy is a skill that can be taught to beginning designers; doing so is essential for creating products that people actually want to use). Engaging in such a pursuit necessitates a level of complexity in learning and design that goes beyond what is strictly necessary. Therefore, it is vital not only to maximise cognitive learning potential but also to acquire the abilities needed to make suitable design judgments. Several studies have theorised a robust link between emotional experiences and cognitive assessments of those experiences (Davis et al., 2020). However, the precise function of individual feelings in the academic process is still up for discussion. For instance, studies have shown that students' capacity to manage abstract thought and problem-solving technique selection can be impacted by their emotional state, which can be both good and bad (Xue et al., 2020). An individual feels a variety of emotions, including fear, amusement, rage, pleasure, regret, and desire (Desmet, 2018). Instead of a single feeling, the mixture of different emotions leads to an enjoyable experience. Research has indicated that unpleasant emotions like perplexity might actually foster deeper engagement with learning materials (D’Mello et al., 2014). These aspects are usually regarded as belonging to the psychological discipline instead of design disciplines. Few design researchers engage in developing these fields and applying them as cross-disciplinary studies involving design and emotion. Emotional reaction and inclusive human concerns are of paramount importance in design. While individuals become increasingly sensitive to dimensions of things that transcend conventional characteristics of usefulness, the need to comprehend and establish emotional and aesthetic connections between people and products grows. Similarly, the idea of experiencing, where the subject and object meet and integrate, is a crucial factor in the development of emotionally significant goods. This is because experience is a place where all faculties, particularly emotions, are aroused. This corresponds to the theory of attachment between people and objects, in which, at the height of love, the border between the personality, as well as the object, threatens to dissolve. More study is needed to determine how emotions affect junior-level design students' capacity for effective emotional response and how certain components of learning interventions promote such responses (Jokinen & Silvennoinen, 2020).

Some design scholars’ writings on design studies rely even more strongly on psychological concepts (Markussen, 2017). In subsequent research, enhanced concepts on how designers might implement the dominant assessment theory from the psychology of emotion are investigated. By analysing the distinctive evaluation components in people's accounts of emotional experiences with items, scholars attempt to develop design-specific assessment structures (i.e. appraisal theory) for emotions such as pleasure, happiness, and disappointment. Markussen (2017) utilises the same evaluation theory and ‘blends’ it with embodied cognition, a major theory in cognitive science, to explain why patients, have such a broad variety of views about utilising interactive healthcare systems. Markussen’s theoretically-informed research of the interaction with a blood-drawing robot gives insight into how consumers produce new evaluations of objects (via the blending of conceptual structures) that evoke fresh or different emotional responses than the individual assessments.

2.3 Enhancing design processes through a human-centred approach

Designers who show the capability to perceive user experience demonstrate a fundamental emotive talent that is crucial for understanding the individuals who interact with their designs (Esser, 2018). This ability, described as 'empathy,' involves the capacity to feel ‘as if one is the user’ by taking on their perspective to relate to situations. The authors emphasised that this ability is derived from an understanding of user experience and design practices. Therefore, proficient designers employ their capacity to comprehend user experience to discern and incorporate the perspectives, feelings, and anticipations of others into efficacious design solutions.

Empathy and user experience are fundamental elements of human-centred design that significantly impact functional design outcomes (Hassenzahl & Tractinsky, 2020). The Council for Interior Design Qualification, whose scope of practice definition guides environmental designers' proficiency on a national level, has noted that the profession relies on human behaviour and theories addressing well-being. Their research revealed that designers' primary responsibility is the emotional needs of people (Professional Standards - CIDA, 2018). Therefore, it is imperative to incorporate training programmes for undergraduate design students that enable empathetic skill development, given that this ability is necessary for designers to achieve their design goals.

The influence of emotions on learners' engagement with relevant learning material is significant. In light of this, it is essential to explore the methods of integrating emotive abilities, particularly empathy, into the undergraduate design curriculum. Furthermore, the field of design education, which prioritises human-centred design, provides an ideal setting for the examination of the impact of instructional methods on the development of sympathetic abilities.

3. Design and emotional concept implementation in the design process

3.1 Emotion-related experience in the design process

The emotions of anger, sadness, disgust, joy, and so on have been discovered to influence junior design students’ thinking. In design practices, sadness or anger is felt when the proposed design project is rejected, and joy and pride are felt when the proposed design project is praised. Sometimes, emotions are evoked outside the design process, such as excitement aroused by good grades and fear and stress caused by studying. However, junior design students are seldom able to notice emotional changes during their design process. They also lack experience in managing their emotions and going through the design process without hindrance. Junior design students may have the possibility to be unable to control their emotional changes. When they are nervous, they may be unable to use their inner strength. When they suppress their anger, they may be carried away by their sense of dignity and make wrong judgments.

The emotion of fear is an unnoticed emotion among designers although psychological studies have argued that fear functions in the human brain (Guerra & Tripp, 2018). Some scholars proposed that designers should be able to avoid failure in reaching the design goals through knowledge and theory and should not have to rely on fear information in thinking, those evoking negative emotions. As long as they learn to deal with potential threats to design material, designers will pay more attention to making decisions and successfully avoid potential dangers. Designers can understand more abstract and potential threats, such as radiation’s harmful effects on the physical body. The experience of fear is conducive to creating a sense of stress. When designers reflect on themselves, they can immediately prevent threats from occurring and return to their original state. Some effective methods of doing so are to calmly observe the changes in the body, such as the increase in the heartbeat.

The emotion of calmness is not presented and noticed because a calm state is the most ‘normal’ state for designers. When designers are in a long-standing space and doing a regular job, they are basically in their comfort zone and feeling calm. When the brain is calm, it secretes dopamine and serotonin normally. The prefrontal lobe also works actively, so designers can think logically and make correct judgments. When faced with problems, designers put aside subjective feelings and other troubles, let their frontal lobes work hard, and think objectively about the impact of these problems. Designers view comprehensive contexts with calm emotion, including whether they are more concerned about the relationship between designers and customers in the long run. If designers keep training themselves like this, they can develop the ability to respond to their emotional changes without losing their logical thinking ability.

3.2 Typical emotions in the design process

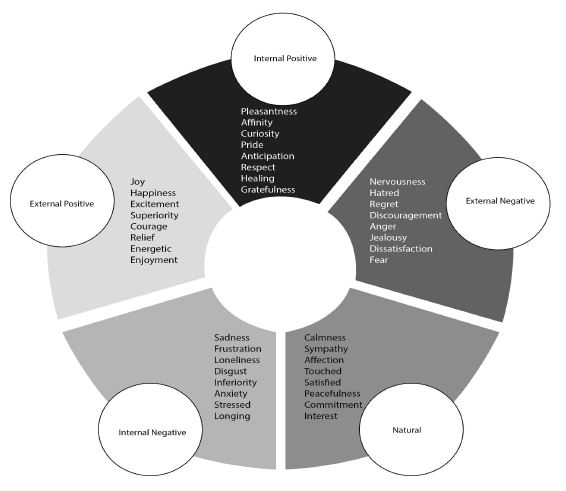

However, many junior design students do not fully notice that the eight primary emotions are categorised based on users’ feedback regarding their design consumption. This means these emotions are elicited by the external environment but may not be active in further cognitive thinking. This is a gap in previous design and emotion studies. In the design process, designers’ emotions are a response to their external environment and influence their decision-making. Emotional changes from users’ viewpoints might not work the same way. Users’ emotions result in their response to their external environment. According to the qualitative research findings in design & emotion studies (Mahan, 2021) and appraisal theory (Jokinen & Silvennoinen, 2020), users' emotions can influence the design process. Therefore, investigating potentially workable emotions in the design process is necessary. By reviewing the appraisal theory, the research team learned some basic emotions. Then, the theoretical descriptions of basic emotions were examined during the review of design studies and practices, and different types of typical emotions were identified in the design process (Tab. 1). Hence, some typical emotions were reconsidered and incorporated into a new model to illustrate the relationships between emotions and typical emotions in the design process (Fig. 1).

Tab. 1 Forty proposed typical emotions were identified in the design process

| No. | Emotion Category | Emotion |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | External Negative | Nervousness |

| 2. | Hatred | |

| 3. | Regret | |

| 4. | Discouragement | |

| 5. | Anger | |

| 6. | Jealousy | |

| 7. | Dissatisfaction | |

| 8. | Fear | |

| 9. | Internal Negative | Sadness |

| 10. | Frustration | |

| 11. | Loneliness | |

| 12. | Disgust | |

| 13. | Inferiority | |

| 14. | Anxiety | |

| 15. | Stressed | |

| 16. | Longing | |

| 17. | Natural | Calmness |

| 18. | Sympathy | |

| 19. | Affection | |

| 20. | Touched | |

| 21. | Satisfied | |

| 22. | Peacefulness | |

| 23. | Commitment | |

| 24. | Interest | |

| 25. | Internal Positive | Pleasantness |

| 26. | Affinity | |

| 27. | Curiosity | |

| 28. | Pride | |

| 29. | Anticipation | |

| 30. | Respect | |

| 31. | Healing | |

| 32. | Gratefulness | |

| 33. | External Positive | Joy |

| 34. | Happiness | |

| 35. | Excitement | |

| 36. | Superiority | |

| 37. | Courage | |

| 38. | Relief | |

| 39. | Energetic | |

| 40. | Enjoyment |

3.3 A Model illustration of the relationships between emotions and typical emotions in the design process

The incorporation of emotion is a significant factor in the design process (Ho & Siu, 2012). It is critical to teach junior design students how emotion may influence the decision-making process and even the ultimate design output. To demonstrate how some typical emotions are classified in the design process, a new concept model (Fig. 1) is built. Not every emotion would be observed in the design process. Some typical emotions are those that are relatively obviously engaged with the cognitive thinking process and decision-making in the design process. Information processing and decision-making mostly influence these typical emotions. They create motivation and influence further actions and judgments rather than only working as a kind of mood or feeling. These typical emotions can be categorised into five main types in Fig. 1: external positive, internal positive, neutral, external negative, and internal negative. This concept can be illustrated with the Fig. 1 model: During the design process, some external dominations, such as material allocation, emphasise stimulation from external sources rather than personal ones (i.e. designers’ consideration). The internal dominations, such as designers’ personal preferences, emphasise personal consideration rather than stimulation from the external environment. Neutral emotions are responses to relatively balanced interactions in both external stimulations and personal consideration. Positive emotions refer to a range of desirable reactions in response to various situations, characterised by pleasant feelings of curiosity, satisfaction, love and pleasure, among others. It is important to note that positive emotions are distinct from pleasurable physical sensations and general positive effects. Negative emotions are any feelings that make designers feel unpleasant and sad. These feelings cause designers to loathe themselves and others, destroy designers’ confidence and self-esteem, and diminish their overall sense of well-being. As the model in Fig. 1 illustrates, typical emotions in the design process can change or shift according to the experience of, investigated information about, and observation of a designer regarding themselves and users. For example, excitement as a part of external positive emotions would be digested and shifted to curiosity as a part of internal positive emotions. This would arouse in designers a deep desire to learn about the unknown and the nature of things. Additionally, anxiety as part of internal negative emotions would be digested and shifted to peacefulness, a mental state of tranquillity that is a part of neutral emotions. When designers’ minds are cluttered with worry and task lists, it can be beneficial to replace them with more peaceful thoughts. The change can enhance or weaken design outcomes. Both emotions and cognitive thinking are significant in the design process. Balanced responses to critical issues result in balanced design choices and processes. The investigation of design processes is informed in part by designers’ experiences with techniques that facilitate cognitive thinking and emotional management in design processes. A balanced approach that incorporates both reason and emotion is the foundation of the proposed model. The possibility of including both emotions and thinking in the design process is investigated. The model contains 40 typical emotions that are a part of the design process. It explains the ideas of emotion, thinking, and emotional management as well as examines their relationships. It is an excellent beginning point for further developing our knowledge of how designers’ emotions manifest, fluctuate and interact with one another. It will influence subsequent design and emotion research in this field and be the starting point for designers’ investigation of emotions.

4. Research methodology

4.1 Research questions and research procedures

Presently, the scope of design education for novice designers is limited to facilitating the application of theoretical knowledge acquired from lecture-based courses on human-centred subjects such as empathic design and user experience, to address issues presented in design studio projects. Regrettably, novice design students frequently have a sense of being overwhelmed while engaging in problem-solving activities. They encounter difficulties in discerning significant attributes of emotional fluctuations and exhibit a deficiency in their capacity to generate effective solutions to problems, although they possess the necessary information. This challenge has been a source of frustration for designers, and researchers across various design fields for decades, highlighting the difficulty of effective and dependable approaches to tutoring novice designers in dealing with aspects affecting the design process that are emotion-related (Shadle et al., 2017). Accordingly, determining effective ways to educate junior design students on the mutable emotional needs of users and audiences is of utmost significance.

Emotional experiences have significant roles in the design process. However, exploring these experiences can be a challenge for rookie design students. Hence, to develop necessary strategies for educating junior design students on managing their emotions during the design process, the research question, ‘What categories of emotions do junior design students discern when engaging in the manipulation of their design process?’ was posed.

To generate potential research directions to address the research questions identified earlier, this study employed a qualitative research methodology utilising focus group discussions to gather in-depth insights into the emotional experiences of junior design students during the design process. Three focus groups were conducted, each with six to eight participants, to accommodate a total of 20 junior design students from a variety of design disciplines, such as interior design, product design, and graphic design. Participants were selected based on specific criteria: they must be enrolled in a design program at a recognised university and have completed at least one year of design coursework to ensure they possess foundational knowledge and experience in the field.

Demographic data collected included age, gender, year of study, and specific design discipline. This information was crucial for understanding the diversity of emotional experiences across different backgrounds within the design field. The focus groups were facilitated by trained moderators who guided discussions using open-ended questions designed to elicit participants' feelings and thoughts about their emotional shifts throughout various stages of the design process.

Each session was audio-recorded with the participant's consent for subsequent transcription and analysis, and it lasted approximately 90 minutes. To ensure a comfortable environment, focus groups were held in familiar settings such as university classrooms or lounges, where students felt free to express their thoughts openly. The discussions focused on identifying specific emotions experienced during key phases of the design process, including ideation, prototyping, and feedback reception.

To find recurring themes and patterns pertaining to emotional experiences, thematic analysis was used to analyse the data. The findings from these focus groups informed the identification of forty common emotions encountered by junior designers, providing a robust basis for developing a novel model that visually represents these emotions. This approach not only enhances the credibility of the research but also ensures that the voices of junior designers are accurately captured and represented in the study's outcomes. These modifications enhance transparency and credibility by providing detailed information about participant demographics and selection criteria within the focus group methodology.

4.1.1 Phase 1: examining the role of emotion in the design process

The first phase of the study involved the adoption of the Phase 1 design project, whereby participants were invited to independently manipulate design projects using an emotion-tracking application during research, material allocation, and idea generation stages. The purpose of this phase was to identify the emotional responses of novice design students during their design processes. Data was not collected in this phase, and the focus was solely on understanding the emotional components involved in the design process.

4.1.2 Phase 2: providing design principles for emotional control

In the second phase, an introductory lecture was conducted to assist novice design students in learning how to manage their emotions during the design process. The attendees of the lecture were present to examine the results of the initial phase, gain comprehension of the optimal emotional reactions that would augment their decision-making abilities in the realm of design, and participate in a range of educational exercises that acquainted them with the concepts of design and emotion. By summarising prior research on psychology, design, and emotions by Southward et al. (2021), the critical principles of design and emotional management in the design process were identified as self-awareness, self-regulation, internal motivation, empathy, and design and emotional competence. Self-awareness refers to the step of understanding self-emotional changes and their effect on others (Gómez-Maureira et al., 2021). Self-regulation refers to the step of controlling disruptive impulses, thinking before taking action, and considering the effect of expressions and self-emotional changes on others (McClelland et al., 2010). Internal motivation refers to the step of working for internal reasons that go beyond profit and status (Reeve, 2018). Empathy refers to the step of understanding end-users and the audiences’ emotions and responses (Zaki, 2020). Design and emotion skills refer to the step of controlling relationships as well as building up emotional attachment with the audience through design executions (Ho & Siu, 2012). These five core components of design and emotion comprise the principles of the design and emotion concept configuration in the design process. Next, Phase 2 of the design project was started. Data were not collected in this phase. The primary goals throughout this stage were to offer participants intellectual stimulation and an enhanced understanding of the linkages between design and emotion, to facilitate their ability to identify and discern their own emotional experiences.

4.1.3 Phase 3: individually evaluating the efficacy of proposed principles

In the third stage, participants were invited to understand their emotional changes by attending a focus group and sharing their emotion management methods. The primary aim throughout this phase was to articulate emotional transformations and assess the efficacy of the suggested principles on an individual basis.

4.2 Research Participants

The present empirical study invited second-year undergraduate students studying design in Hong Kong to participate. The participants were unfamiliar with the concept of emotions in the design process, and this fact positively contributed to strengthening the generalisation of the research results. The participants in this study developed a foundational grasp of design principles after engaging in a two-year programme that covered many aspects of design, such as design thinking, user experience, and design outcomes. Additionally, they gained a rudimentary comprehension of the design process within a very brief timeframe. Nevertheless, their attitudes towards design and established methodologies for controlling the design process have not yet fully evolved. Although participants were not conversant with the concept of 'design and emotion,' their incremental application of these concepts to the design process was anticipated, and reflections on their design manipulation would amply reflect the emotional transformation that had occurred. The study included 30 participants who were natives of Hong Kong and spoke Cantonese as their mother tongue. They received an English-medium university education and were fluent in English, as well as being able to acquaint themselves well with Western concepts.

5. Research findings

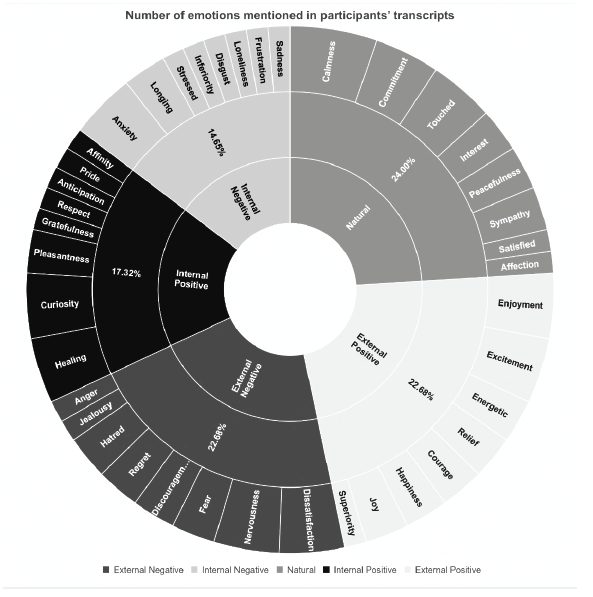

5.1 Types of emotions identified in the design process of junior design students

After obtaining experience in the design projects in Phase 1 and Phase 2, the participants were invited to share this experience in the focus group. Feedback on the participants’ design projects was collected through their discussion. The data were gathered and presented in a transcript. The required workload in Phase 1 and Phase 2 design projects was similar. Based on the feedback from participants, 40 emotions, including loneliness, disgust, shame, inferiority, anger, and anxiety, were identified (Fig 2). Calmness was the emotion mentioned most in the focus group (5.33%; Fig 2), followed by anxiety, touched, commitment, healing, curiosity, excitement and enjoyment (4.00%; Fig 2). Then there followed by hatred, regret, discouragement, fear, longing, sympathy, peacefulness, interest, pleasantness, joy, happiness, courage, relief and energetic (2.67%; Fig 2). Finally, the least frequent emotions mentioned are anger, jealousy, sadness, frustration, loneliness, disgust, inferiority, stressed, affection, satisfied, affinity, pride, anticipation, respect, gratefulness and superiority (1.33%; Fig 2). The percentages of the emotions are summarised in Fig 2.

6. Discussions about the research findings

As per the participants' feedback, they had not received prior education in emotion management or self-awareness, indicating unfamiliarity with these concepts. A few participants expressed uncertainty about the type of emotions experienced while working on the assigned design task.

Participants pointed out that designers would work better under a calm state of mind because they could think logically and make good decisions. Participant 5 mentioned, ‘I think a calmer and less emotional state can improve my learning because I can receive more knowledge when I am calm’. The feedback from the participants indicated that when feeling calm emotions, designers put aside their own feelings and other problems and think about the design problems objectively. This finding would enhance the knowledge of emotion’s functions in the design process as mentioned in the literature review. Participant 5 mentioned, ‘I think I feel better when a person settles down or is still because they will concentrate. I think a peaceful and calm environment is better because if there are too many people talking on the side, I can’t concentrate on it, but if it’s alone, I can go and think clearly about it -what an idea’. Designers have to consider a wide range of situations, including long-term concerns about the relationship between designers and customers. Calm people will be able to make good decisions because they will have peace of mind. Participants’ feedback reflected that if designers keep practising calmly, they will be able to learn how to respond to problems quickly without giving up their logical thinking.

Participants also emphasised that both negative and positive emotions can help designers work effectively from different aspects. People experience a wide range of feelings as mentioned in the literature review (Desmet, 2018; Walther et al., 2017). The experience is more satisfying since it is not dominated by any one emotion. Positive emotion helps designers communicate with others. Participant 6 stated, ‘I think it may be more positive to be able to communicate with other people about emotions, and it will be easier to learn if you communicate or talk with other people more’. Participant 4 stated, ‘I feel happy and excited. Listening to my own preferences will make me more comfortable, or I think anxiety will be effective for me because when I’m stressed, I want to be anxious and want to get things done quickly’. Alternatively, some participants argued that designers should be able to avoid threats by relying on knowledge and theory rather than on fear-based information. For example, product designers can prevent risk as long as they learn to cope with possible threats while selecting raw materials. Participants agreed that designers can comprehend more abstract and potentially dangerous concerns. Participant 1 mentioned, ‘I would feel the difference between me and Cherry. In my case, personal comfort is the priority. Cherry will be able to cope with life first. It seems that I have been forced out of some ideas, so I prefer to go there and find a point that interests me, and then I will go deeper into this and do my homework’. Participants’ feedback confirmed that emotions’ potential to influence danger perceptions extends to a fundamental mechanism inherent in threat detection. Designers were instructed to make fast judgements about whether target persons were carrying firearms or neutral items while feeling various emotions. Anger increases the likelihood that neutral things will be mistaken for those associated with violence, but not vice versa. Negative emotion-induced bias in design conceptions can be corrected with appropriate skill.

Some participants emphasised that they work better when curious. Participant 1 mentioned, ‘Personally, I think it is more effective to be curious and interested and achieve my expected learning outcomes . . . Because only when I am interested in such things, I will first have the motivation and look forward to the results, so I will have more strength to do it first and keep trying to design homework and collect various materials. A curiosity, if you are interested in doing it, it will not be so hard’. Participant 3 concurred, ‘I think when I learn something that I find interesting and when I talk about it in class, I am interested in this and I am passionate about a certain design . . . In other words, you will push yourself to learn; that is, you will make yourself want to learn more, and if you have homework at the time, it will help you learn’. Participant 4 stated, ‘I think high emotions will help me learn a lot because excitement tells me that my mental state will be better . . . This kind of emotion will make me learn faster’. Some participants pointed out that curiosity led them to do more practice. Participant 2 stated, ‘Actually if you’re not interested in this kind of thing, you will be unable to achieve your expected learning outcomes’. The feedback from participants indicated that the concept of curiosity plays a role in the design process, in line with previous scholars’ findings (Harley et al., 2019; Montambeau, 2018). Curiosity is one of these emotions that often results in information-seeking and motivating activities. A design using curiosity principles can adequately arouse the interest of participating designers in engaging with the design.

7. Conclusion

During the early 2000s, there was an upsurge of interest among design researchers in exploring the interplay between emotional factors and design. A significant amount of research was conducted during this period focusing primarily on the user's perspective. The design process encompasses not just rational and logical considerations but also designers’ techniques, experience, and abilities, as well as their reactions to the external environment or the stimulants in their immediate vicinity. These ideas offer an adequate theoretical foundation, but few research studies have examined, during the design process, how junior design students’ emotions evolve. Junior design students may have difficulty processing information from sources that require extensive engagement with other people. The need to bring these ideas into the design processes of junior design students and influence the manipulation of these processes has been identified. Thus study identifies and analyses the forty common emotions that junior design students experience at during the design process, also highlights the importance of emotional awareness in an effective design practice. Getting a handle on those emotions is important not just for helping students refine their own individual design processes, but also for making design education better. Understanding how emotions affect decision-making and cognitive functioning will enhance educators’ abilities to prepare students for the nuances of design problems. The results highlight the need for integrating emotional intelligence training within design programs, so that students can cultivate the skills necessary to regulate their emotional reactions. This practice positively impacts students on a personal level and also allows them to create user-centered designs that find greater emotional connection with their target consumers. Then, in the longer term, further research should consider the effect of emotional management training on design outcome and student satisfaction. It is also going to be crucial to investigate how different teaching methodologies can be adapted to integrate emotional intelligence more effectively. Furthermore, interdisciplinary research exploring the relationship between psychology and design would likely provide useful knowledge on how emotional dynamics affect creativity and innovation across genre of design. In summary of it all, let us not forget we are training designers with emotions, and (good) design must interpret and feel what emotions are happening with the users it is designed for. In an increasingly complex world, this holistic understanding will lead to design solutions that are more considered, more empathetic and more impactful over time. These changes offer a wider lens through which to consider the study’s findings’ impact on design education and practice, and point towards future research opportunities.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the participants who took part in this study. This research was conducted by following the ethical guidelines outlined. All participants provided informed consent, and their privacy and confidentiality were strictly maintained throughout the study. We are grateful for their valuable contributions, which made this research possible.