1. Introduction

Between 2021 and 2022, public profiles of many Indian Muslim women were "auctioned" with their photographs and personal information to various users on an open-source platform, GitHub. These applications, known as S*lli Deals and B*lli Bai, would distribute pictures of prominent Indian Muslim women on social media with derogatory messages such as "your s*lli deal of the day is-", which were shared by users throughout Twitter (Pandey, 2021).

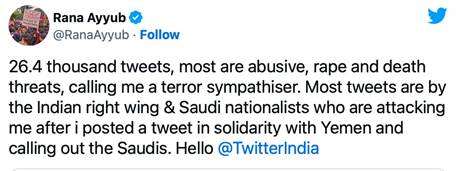

Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter have become an intrusive part of our political and public life (Jose, 2021). These platforms are full of instances of online genderbased violence (OGBV; Figure 1 and Figure 2). OGBV are those instances on digital platforms that target marginalised genders at the intersection of religion, caste, and sexuality, which manifests as impersonation, doxing, spamming, cyberstalking, tracking and surveillance, verbal harassment and non-consensual dissemination of private messages and photos with malicious intent. In India, those at the receiving end of such disturbing online harassment are women, the LGBTQI+ community, non-binary, trans persons, especially from non-Hindu, oppressed caste backgrounds, who make themselves and their dissenting thoughts, voices and opinions visible against the incumbent far-right government and their Hindu supremacist ideologies.

From 26.4 thousand tweets, most are abusive, rape and death threats, calling me a terror sympathiser. Most tweets are by the [Tweet], by Rana Ayyub [@RanaAyyub], 2022a, Twitter. (https://twitter.com/ranaayyub/status/1485728200890413056)

Figure 1 Screenshot of a renowned Muslim Indian journalist describing her experience with online gender-based violence

From Frustration is not the right term for this [Tweet], by Rana Ayyub [@RanaAyyub], 2022b, Twitter. (https://twitter.com/RanaAyyub/status/1591994568983171073)

Figure 2 Screenshot of a Twitter post by an Indian journalist describing her experience with online gender-based violence on Instagram

The increase of OGBV has also come alongside the increase of the Indian far right wing in these spaces. One such instance is the alleged use of the Tek Fog app to harass women journalists with abusive tweets, in which there are allegations of the involvement of influential people linked to India's ruling party (PTI, 2022). Under this context, a browser plugin, Uli, was developed to detect and moderate OGBV on Twitter.

In addition to their keywords, hashtags, algorithms, policies, and digital infrastructure (Johnston, 2022; Monea, 2022; Suzor et al., 2018), the visual language and identity design of social media platforms do not take responsibility for the reproduction of gender-based violence, and through this, they remain complicit in propagating online violence and hate speech. In this case study, the authors of this essay - who were involved as visual designers in creating Uli - discuss the process of co-designing a visual identity and narrative design for Uli.

The goal of the co-design process was to support the presence of Uli and to represent the ideology and collective labour of the interdisciplinary team that developed the tool. This case study and visual essay concludes with the challenges and dilemmas faced by the visual designers of Uli during the process of creating the visuals.

2. Background on Uli

Uli is a user-facing browser plugin that is co-created to address issues of OGBV through a feminist lens and aims to find ways in which moderation can empower users most affected by OGBV (Budhwar, 2022). It supports users in moderating instances of OGBV they face in different Indian languages, specifically focusing on people situated at the margins of gender, caste, religion and sexuality (Budhwar, 2022). In order to make online spaces like Twitter habitable, Uli's development was led by technologists and researchers in active participation with activists, community influencers, journalists, and writers, who are engaged in the struggle against interwoven caste, religion, gender and sexuality-based violence in both online and offline spaces.

The browser plugin primarily redacts slurs and abusive content in Hindi, Tamil and Indian English while also allowing the archiving of problematic tweets. Uli uses a crowdsourced list of slurs in Indian languages - one which users can contribute towards - detects them on Twitter feeds, and hides them in real-time. The machine learning feature uses pattern recognition drawing from previously tagged OGBV posts to detect and hide problematic slurs from posts on a user's feed.

The plugin is a joint project initiated in July 2021 by the Centre for Internet and Society (CIS) and Tattle Civic Technologies, with its development funded in the first year by Omidyar Network India as part of their Digital Society Challenge grant (to know more about the project, and the entities behind Uli, visit the following websites: Uli [https://uli.tattle.co.in], CIS [https://cisindia.org], and Tattle [https://tattle.co.in]). The CIS is a non-profit organisation undertaking interdisciplinary research on digital technologies and the internet from policy and academic perspectives. It focuses on digital accessibility, access to knowledge, intellectual property rights, internet governance, telecommunication reform, digital privacy, and cyber-security. The Tattle Civic Technologies is a community of technologists, researchers, and artists working towards a healthier online information ecosystem in India. The Tattle builds tools and datasets to understand and respond to misinformation in the country.

Uli, the machine learning tool, uses approaches from the machine learning field, which suggest building scaled-down tools while integrating feedback from endusers (Vidgen & Derczynski, 2020; Waseem, 2016). Between July and October 2021, the CIS and the Tattle conducted different formats of online interviews and held four focus group discussions with which they were able to engage more than 50 activists and researchers working in sexual, gender, and minority rights spaces. To capture and understand aspects of harm and violence for the plugin, the Uli team invited seven expert annotators for English, Hindi and Tamil who have been at the receiving end of OGBV to annotate 7,500 posts per language1.

3. Visuals of Resistance

At its core, Uli is an act of resistance, which is also consciously reflected in its visuals. The visuals were designed in a participatory manner to represent Uli's goals while visually explaining its function and labour in creating feminist technology while making it accessible to internet users of India. The aim was to showcase the interdisciplinary work of the team along with an infrastructure that relied on a feminist manifestation of machine learning. The visuals show the coming together of humans and machines to co-create an output of love, labour, and resistance which became the foundation for its visual design and narrative.

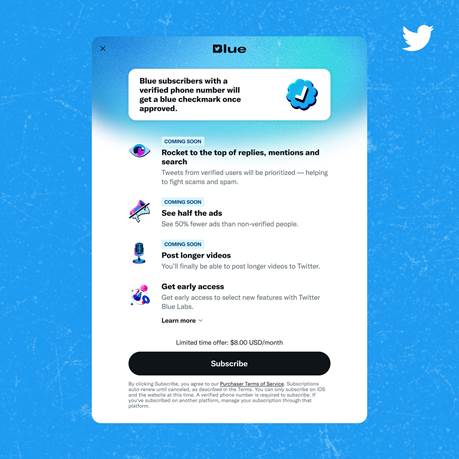

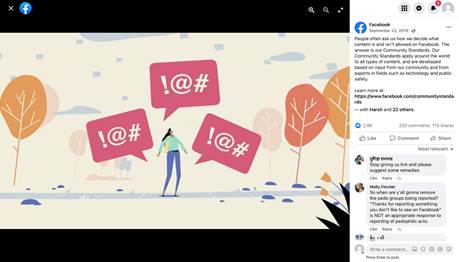

The secondary goal was to create an alternate visual aesthetic to the dominant, existing visual language that has become synonymous with spaces that further OGBV, such as Instagram, Facebook and Twitter. The visuals of these platforms have played an important part in keeping the platforms' heteropatriarchal, racist, casteist and heteronormative bias intact. Sleek design, saturated colours (Figure 3), and distinct illustration styles dominate these platforms, often depicting scenes of positivity, visually mythologising the idea of building a utopian, happy world (Figure 4). They help make big tech companies look friendly and concerned with communities, which is largely the opposite of what they are (Gabert-Doyon, 2021).

From we’re relaunching @TwitterBlue on Monday - subscribe on web for $8/month or on iOS for $11/month to get access to subscriber-only features, including the blue checkmark [Tweet], by Twitter [@Twitter], 2022, Twitter. (https://twitter.com/Twitter/status/1601692766257709056)

Figure 3 A graphic uploaded on Twitter's page on December 11, 2022

From People often ask us how we decide what content is and isn't allowed on Facebook. The answer is our Community Standards [Status update], by Facebook [@facebook], 2019, Facebook. (https://m.facebook.com/facebookappIndia/posts/people-often-ask-us-how-wedecide-what-content-is-and-isnt-allowed-on-facebook-t/2490127257690847/)

Figure 4 Facebook post with a socially conscious illustration, representing a woman of colour drawn in a proportionally exaggerated illustration style with saturated colours. Intended to reassure that it seeks to control hate-speech against marginalised communities, despite opposite evidence

The name Uli was proposed by the qualitative researcher and Tamil Language lead on the team after a collaborative brainstorming session conducted by the visual designers. “Uli” is a term in Tamil for a simple but dextrous tool - a chisel, that allows one to carve a room of one's own or courtyards where people can come together and share stories of resistance - a narrative designed along the ideologies and principles of the tool itself.

The inspirations for Uli's visuals were focused on many tangible products, activities, and the people behind them. During early phases of development and annotations, the team envisioned the tool to be represented by a "sewing machine" to honour its slow, mindful labour and to represent Uli's use of machine learning technology.

Metaphorically the tool was later imagined, during conversations between annotators, developers, researchers, and designers, as a quilt-making process that reflects intimate, gendered histories of suturing, tailoring, fabricating, stitching, patching, and moulding the world around us. Quilts and quilt-making are forms of a cloth-based narrative, an art part of many cultures. Like this tool, quilts are often made collaboratively and are both personal and communal objects that empower and celebrate. The visuals of Uli attempt to accurately represent the emotional labour that went into developing the tool while telling a story about its creators and their historical and cultural contexts through its design, materials, and stitches.

As visual designers, we then extended this concept into visuals that could be translated as arts and crafts like embroidery, stitching, quilting, and safe spaces like courtyards as the visual of a space where communities convene. Embroidery and textiles have often been outputs of a collective effort, especially in the worlds of women in our subcontinent. Uli's inspiration was people and their work-crafts, handwork, hard work, imperfections, and collective participation (see Chandrashekhar, 2015; Delhi Crafts Council, n.d.).

As a collaborative visual design decision, we co-dreamed this tool, like a patchwork quilt, to be co-created in a courtyard of women, LGBTQ+ persons, dancers, singers, and all communities that the internet otherwise marginalises. This courtyard would be where the work of resistance and resilience is celebrated. In the chosen visual approach, we imagined folks from this community sitting together with their experiences, their tools like "threads" and "sewing machines", in this case: artificial intelligence and machine learning, to stitch together beautiful patches inspired by their stories as an act against OGBV (Uli, 2022b). These ideas translated into visuals inspired by fabric, quilts, stitches and the kind of motifs or patterns that appear in them. The illustration for Uli's website landing page was inspired by a certain nakshi kantha (Figure 5; see Morris, 2011) embroidery visual. A kantha, a kind of embroidery craft or the craft where old saris are stacked on each other and hand-stitched from Eastern regions of India and Bangladesh, takes months or even years to be finished, handed down through generations, from grandmother to mother, to daughter.

This post is adapted from the Uli newsletter updates sent in March and April 2022, by Uli, 2022b. (https://uli.tattle.co.in/blog/making-of-mar2022/)

Figure 5 Uli newsletters designed for the community that supported and contributed to its creation, showcasing the various textile-based influences

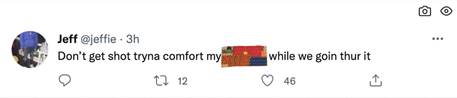

To embody the craft, we conceptualised phrases to describe every action Uli could do as a tool. We branded the blurring of slurs, a key feature of the tool, into the term "patched" and envisioned that each time "a patch" is stitched upon words that our community has flagged, it stands as a symbol of communal resistance (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

From This post is adapted from the Uli newsletter updates sent in March and April 2022, by Uli, 2022b. (https://uli.tattle.co.in/blog/making-of-mar-2022/)

Figure 6 Tweet showcasing the concept of a qui lt-making patch to redact slurs

From This post is adapted from the Uli newsletter updates sent in March and April 2022, by Uli, 2022b. (https://uli.tattle.co.in/blog/making-of-mar2022/)

Figure 7 Tweet showcasing the patch in the final version

Uli's logo (Figure 8 and Figure 9) resembles this courtyard of moving ideas and communities as an ode to the efforts of different groups, organisations, and movements that strive to empower each one of us (Uli, 2022b).

4. Challenges

A challenge we face designing visuals differing from mainstream tech visuals is the lack of their scalability. What has made dominant visual styles of tech tools and platforms scalable is that they are easy to replicate and do not need any specific artist to work on them. On the other hand, ours is designed to look hand-made, which can become a challenge when its visual style needs to become ubiquitous and adaptable for different channels and mediums without requiring considerable resources and time. Since the visual aesthetic of social media spaces and their extensions are so homogenised and consistent across platforms, they create an image of stability and trustworthiness. In contrast, an alternate visual style like Uli's that attempts to represent transparency, accessibility, and collective labour with its simple illustrations, typefaces, and symbols is at the risk of being perceived as untrustworthy due to its unpredictability and irreplicability.

The biggest ethical conundrum we carry is creating visuals for online spaces inspired by various arts and crafts that belong to communities of women that do not necessarily have a presence in these online spaces. There is a risk of appropriating a culture not shared by the visual designers' communities. One of our original ideas was to approach communities of local weavers and craftswomen whose style inspired the visual language of the project and to request their participation in this project. However, due to resource-related constraints that often bind independent projects of resistance like Uli, this part of the process did not get off the ground. However, a truly participatory visual design process is still the ideal approach when sharing the visual culture of grassroots work.

5. Conclusion

One of the future goals for the plugin is to keep expanding the slur list, as slurs on social media change fast, and the list will continue to evolve to keep up and detect slurs. The dataset is also planned to be updated to detect hate speech which also evolves in a similar way. The tool will also grow to include more languages in its next phase. An upcoming feature of Uli will allow users to involve their friends and community to act on problematic tweets, combat online hate speech, and support each other.

When it comes to the visuals and what they depict, it is important to note that even those designed with the best intentions mask, reproduce, and propagate gender-based violence in online spaces. There is a need to continue a discourse that discusses and envisions new visual cultures, models, and artistic expressions to represent technology that can serve not only as a critique but act as a means to make violence visible. At the same time, when visual art, design, and media work with emancipatory spaces to mitigate gender-based violence, they can support re-imagination, re-learning and reparation aimed at reconstructing the way we deal with violence.

texto em

texto em