Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a branch of computer science that refers to the ability of computers or machines to solve problems that normally require human intelligence.1 Science has recently witnessed the ability of AI to manipulate data using algorithms and apply this knowledge to solve practical clinical problems. (2) In 2017, the journal Nature published an article in which an AI technique was able to diagnose skin cancer as efficiently as dermatologists. (3 In 2018, another article claimed that AI had even better diagnostic ability to skin cancer than physicians. (4 In addition, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the USA already authorized the first AI device to diagnose diabetic retinopathy without a physician’s help in April 2018. (2

Medicine has not been integrating AI technology as quickly as it has been advancing. The main difficulties are the question of responsibility, the use of health data (privacy concerns), concerns about cybersecurity, and ethics considerations. (5-6) Furthermore, for there to be a correct application of AI in healthcare, general public trust and health professional support are essential. Although recent efforts have been made, there is limited research exploring patient perceptions on AI application in medicine. (7 In a 2020 study, authors reported that most participants showed confidence in AI providing medical diagnoses, sometimes even over human physicians, but generally expressed concern with surgical AI. (8

Oh et al. conducted a survey among doctors to assess their attitudes toward medical AI applications. It showed that doctors have positive attitudes toward AI implementation in the healthcare and that most physicians assumed that their roles will not be replaced by AI. (9) Despite agreeing on the usefulness of AI in the medical field, most health professionals lack a full understanding of the principles of AI. (10-11

Different algorithms using AI have been proposed in the field of otorhinolaryngology. In terms of image-based analysis, images acquired by endoscopes, stroboscopes, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and multispectral narrow-band imaging can now be interpreted by AI. (12 In voice-based analysis, AI can be used to evaluate vocal fold disorders by analyzing and decoding phonation itself. (13 In medical device-based analyses, AI can also be used to evaluate tissue and blood test results, as well as the outcomes of otorhinolaryngology-specific tests (e.g., polysomnography or audiometry). (14 AI has also been proposed to support clinical diagnoses and treatments, decision-making, the prediction of prognoses and disease profiling.

The aim of this research study is to explore general public and health professionals’ perceptions of AI in otorhinolaryngology, and evaluate relationships between demographic characteristics and disposition toward AI.

Material and Methods

Survey Development

We conducted a cross-sectional study using a self-completed online questionnaire. This questionnaire was carried out using the Qualitrics® platform and the answers were recorded with the IP address of the device used and subsequently validated. A literature review was first performed to identify the survey items, which should provide an estimate of individual attitudes and beliefs towards the use of AI in healthcare practice. The 9-item questionnaire examined aspects related to the application areas for AI in otorhinolaryngology, namely diagnostics, decision making, surgical procedures and monitoring of different pathologies. For each question, participants had to choose on a scale from 0 to 10 (where proximity to 0 represents AI and proximity to 10 represents the human) which healthcare provider they would prefer. The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Sample

The participants were opportunistically recruited over a 4-week period beginning May 2023. The eligibility criteria for participation were as follows: (1) 18 years or older, (2) able to understand the information describing the study, and (3) able to provide consent.

Patients were divided into different generations according to age: Generation Z (18-25 years), Generation Y or Millennials (26-41 years), Generation X (42-57 years), Baby Boomers (58-67 years), Silent Generation (>67 years).

The participants were previously informed about the aims of the questionnaire and they voluntarily participated. Participants anonymity was ensured, and the responses were identified by participant identification numbers only.

Statistical Analysis

All the surveys after completed were entered into a database in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation). Descriptive statistics were used to describe the sample by gender, age, nationality and profession. Multivariate regressions were used as appropriate to identify associations between demographic factors and responses. The results were deemed statistically significant if p<0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (SPSS 15.0 for Windows, IBM Co., Chicago, Il, USA).

Results

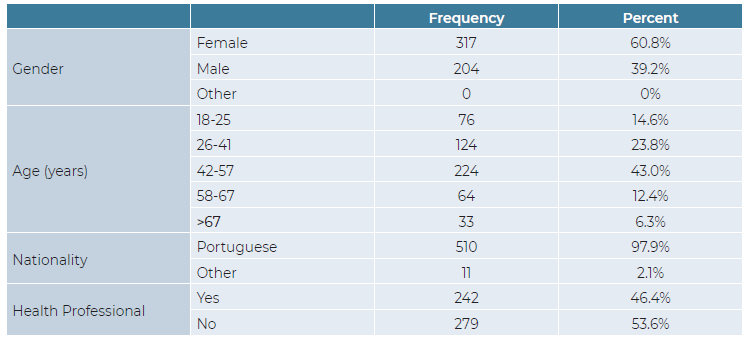

The survey was answered by 770 participants over a period of 1 month. Data was collected from only 521 questionnaires as 249 had incomplete information. Demographics of the participants are outlined in Table 1. Most of the sample (317/521, 60.8%) were female, Portuguese (510/521, 97.9%) and between 26 and 57 years old (348/521, 66.8%). Moreover, nearly half of the respondents were health professionals (242/521, 46.4%).

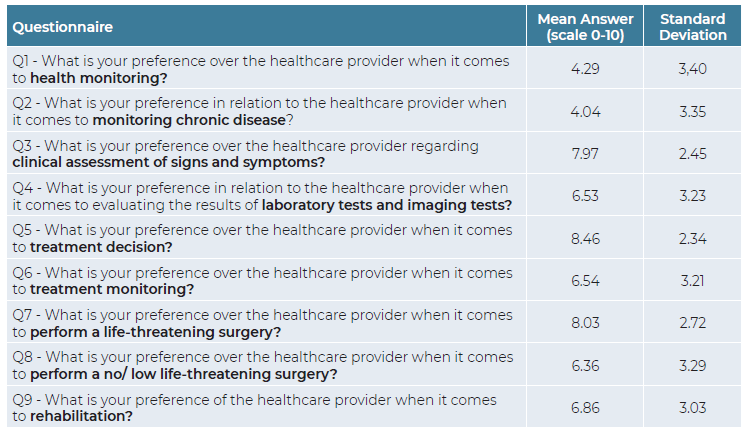

The full breakdown of the questions and answers are given in Table 2. In general, the answers to the questionnaire approached the middle of the scale (from 0 to 10). Health monitoring and chronic disease monitoring (Questions 1 and 2, respectively) are the only items where AI was preferred over human healthcare providers. On the other hand, deciding on treatment and performing life-threatening surgeries (Questions 5 and 7, respectively), were the items in which the preference for human healthcare providers was most pronounced.

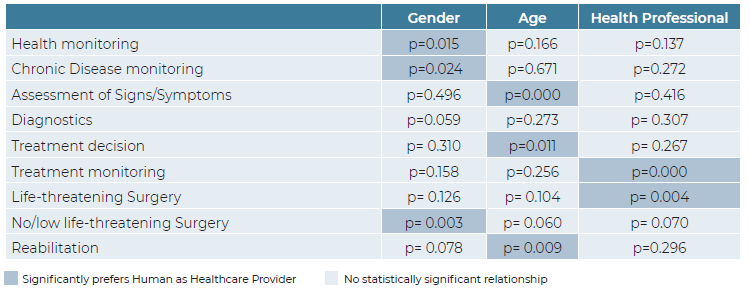

On average, women significantly more often prefer a human to perform health monitoring (Question 1), chronic disease monitoring (Question 2) and to perform no/low-life threatening surgery (Question 8), when compared to men (Table 3). Both in terms of clinical assessment of signs and symptoms (Question 1), treatment decision (Question 5) and rehabilitation plans (Question 9), the age groups representing the youngest (18-25 years old) and oldest (>67 years old) participants more often prefer humans to perform these tasks.

Table 3 Significance map detailing the significance of the relationships between the responses and the panel of demographic characteristics.

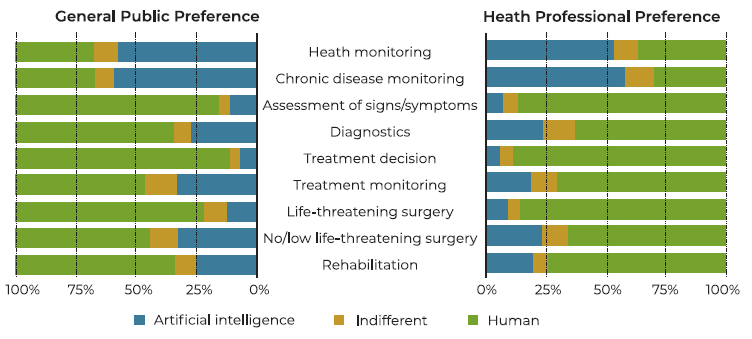

The difference between general public and health professionals perception on AI in otorhinolaryngology is shown in Figure 1. The only statistically significant differences between groups concern questions 6 and 7. Health professionals, more often prefer a human health provider for treatment monitoring (7.18 ± 2.85) when compared with the general public (5.97 ± 3.40). In what concerns life-threatening surgery, health professionals showed (8.32 ± 2.53) greater preference for human health providers than the general public (7.78 ± 2.86).

Discussion

AI techniques can potentially assist physicians, namely otorhinolaryngologists, to take better clinical decisions or even perform some tasks autonomously or semi-autonomously. The successful integration of AI technology into routine clinical practice, depends not only on numerous technological progresses, but also whether the general public and health professionals can accept and trust it.

This study suggests a certain openness towards AI applications in otorhinolaryngology. Our findings aligns with recent research showing that general public perception and optimism of AI as a whole has risen markedly. (15) As it was described by Stai et al., most participants showed confidence in AI providing health monitoring or chronic disease monitoring, even more than humans. (8) Many patients could feel that an AI gives them additional certainty in their diagnosis. (16) Our study is also in agreement with literature when it comes to health provider preference to perform surgery, particularly life-threatening surgery. (8) Most participants preferred human health providers to perform life-threatening surgery. Stai et al. hypothesized that being male seems to align with a narrative of higher tolerance to risk taking, and thus explain the relationship between these demographic variables and the preference for AI. (8) In our research, men significantly more often prefer AI technology to perform health monitoring, chronic disease monitoring and to perform no/low-life threatening surgery, than women.

The distribution by generations that was carried out in this study not only has the function of dividing age groups, but also of showing different patterns of access to technology. While Generation Z was born with the regular use of computer technology at home, Baby Boomers began contact, in many cases, when they were over 40 years old. There are also intermediate cases, such as Millennials who began to regularly use technology in their adolescence. We hypothesized that the statistically significant preference of participants over 67 years of age for the human component is due to a late start to regular technology use. However, this hypothesis does not allow us to explain why Generation Z also prefers human health care providers. A certain emotional dependence on the authority presented by the human factor in health care may be the reason to this finding.

Radiologists were the first health professionals to be exposed to the AI revolution and they already agree that AI could be a useful assistant. (2 This positive attitude was perceptible both in Europe17 and abroad18. Among medical specialities, general practitioners view of AI may be the more skeptical, as they claimed that AI would not improve the efficiency of their work or reduce the administrative burden. (19) In our findings, health professionals have an overall positive opinion on AI. However, when compared to general public, health professionals, more often prefer a human health provider for treatment monitoring and to performer life-threatening surgery.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to show the perception of the general public and health professionals in the application of AI in Portuguese Otorhinolaryngology. However, the interpretation of the results of our research must consider the following limitations. First, this is a cross-sectional questionnaire study that provides only momentary perceptions on AI, rather than how these may change over time. The fact that participants were recruited manly from Portuguese population may limit the generalizability of the findings. Also, as our survey was based on an online questionnaire, we left out those who were unable to read or use computer tools.

Conclusions

With increasing research on implementing AI in healthcare, more attention is given to general public and health professionals perception and acceptability of this type of technology.

This study has demonstrated that there are significant variations in AI perception, depending on gender, age and profession. There is a need for greater awareness among the public and health professionals for ensuring the acceptability of AI research and its successful integration into clinical practice in future.

Acknowlegments

We would like to thank Professor Fátima Gameiro for SPSS® data analysis and Iris Neto, Mário Guerreiro, Tomás Capela Martins for their contribution on the development of the questionnaire.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Data Confidentiality

The authors declare having followed the protocols in use at their working center regarding patients’ data publication.