1. Introduction

Reflecting wide social changes towards more equality and inclusion, recent years have witnessed a clear increase in research projects employing a participatory design. In an attempt to address the hierarchical differences between the researcher and the researched, these projects highlight the expertise of the latter and assign them responsibilities within the research process. Evidently, there are clear benefits in democratizing the research agenda and engaging participants in the design of the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data. This is particularly the case when it comes to marginalized groups, who are given voice and participation rights.

However, there seems to be a lack of systematic discussion about the exact ways in which the participants become involved in practice (Nind, 2008; Rix et al., 2019), and projects have emerged that are presented as participatory even when their involvement remains minimal (Brown, 2022; James & Buffel, 2022; Seale et al., 2015). One possible reason for this is the still new shift of power from the researcher to those making the research possible. Another is the claim that participants lack both the experience and knowledge required to conduct research, a skill that clearly falls within the researcher’s repertoire.

So, despite all the ideals of egalitarian participation on shared negotiated floor, the researcher/participant roles remain clear and asymmetrical in power (Areljung et al., 2021; James & Buffel, 2022), with the first acting as a neutral controller drawing on scientific expertise and the latter as the subject allowing access to a much-desired hidden truth. This leads us to question whether participants can and should actually conduct analysis and interpretation of data. It also bears implications about whether and to what extent the researcher and the researched can cooperate as equal partners, share their power, and eventually transform their lives, the underlying principle of the participatory approach.

This paper aims to address the call for a more nuanced discussion of the researcher/participant relationship in participatory approaches by critically discussing the interactive and dialectic process of lay user’s/researcher’s co-creation of accounts in the research interview context according to an interactional sociolinguistic perspective. We draw on constructionism and interactional sociolinguistics (IS) to analyze the discursive work of the researcher and the participants in a discourse-based interview extract as they negotiate their roles in situ and, by doing so, lead to a mutually created account of the phenomenon.

The paper starts by discussing the potential of a constructionist and interactional sociolinguistic approach to participatory research and then turns to first/second order accounts. It then moves to our study and the analysis of an excerpt from one interview on formality in workplace emails to illustrate our arguments. We close by summarizing and drawing implications for future research.

2. The Participatory Approach, Constructionism, and IS

Recent years have witnessed significant developments and a clear rise in participatory approaches and have acknowledged their benefits, particularly for marginalized groups like the disabled and the elderly. The hands-off bottom-up approach, where participants decide what to investigate, how best to investigate it, and which data are appropriate and significant for collection (Holmes & Stubbe, 2015), has been widely used and remains popular in sociolinguistic and intercultural studies for some time now. However, outside the (socio)linguistic realm, the claim of full egalitarianism in all stages of the research process has turned out to be problematic in practice. Multiple studies (e. g. Brown, 2022; Seale et al., 2015; Tilley, et al., 2021) and systematic literature reviews (James & Buffel, 2022; Nind, 2008; Rix et al., 2019) show a lack of clarity and detail about the way in which participants are involved in certain stages of the research process. Claims have been made that participants have been excluded from data analysis and dissemination of findings in projects that purport to be fully egalitarian.

This has led to a disagreement on whether participants, as untrained researchers, can and should participate actively in data analysis (Brown, 2022). On the one hand, participants are positioned as not having the required knowledge or experience to understand and take methodological decisions or fully realize ethical consequences. In this line of thinking, methodological concerns should be left to the researcher, who has the expertise in conducting research by highlighting the participants’ viewpoints and ensuring their well-being. On the other hand, the participants’ direct experience renders them most suitable to make decisions regarding which data are important and appropriate for collection. Also, the participants’ understanding of ethical issues that apply in their context is informed and often at least as nuanced as the researcher’s.

Insights from work involving marginalized groups (outside the linguistics literature) point to the participants’ ability to learn to engage in the analysis if they are open to new socially situated ways of viewing participation away from traditional research analysis. Recent scholarship has challenged the view of the participant as an uninformed outsider to the research process. Nind et al. (2016, p. 547) argue that participants can learn to undertake data analysis by being immersed in the research environment, by learning from the challenges they encounter and by engaging in mutual contribution to knowledge with others. Rix et al. (2019, 2022) similarly point to the emergent nature of participation in the analysis and dissemination of findings involving the disabled, which is democratic and negotiated in situ. Analysis can be enriched in various ways: by being reflective (Gadd, 2004), by developing and sustaining sensitivity, trust, and rapport (Tanner, 2012; Tilley et al., 2021), and by allowing for more project time (Areljung et al., 2021; James & Buffel, 2022). Other ways involve going for a rich mix of different types of expertise, alternating the lead in different rounds of analysis between participants and academics (Seale et al., 2015; Tilley et al., 2021), and adapting it to particular research objectives and contexts (Brown, 2022).

Underlying this perspective is the pragmatist stance that analysis is always from somebody’s point of view. In this line of thinking, there should be no issue when participants (including even people with learning disabilities) engage in the analysis.

At the same time, participation is highly relational, uncertain, and unpredictable. It is inevitably a “messy” space (Seale et al., 2015, p. 491), involving tensions and challenges, the shared space of reciprocal learning, where all the parties involved learn and relearn through and in interaction (Brown, 2022; Nind, 2011). We argue, therefore, that research methodology can discuss further both the process and the ideals that govern our practices, which can then translate and improve research praxis.

This paper adds to the above insights from the socio-linguistic discourse analytic realm by drawing on a constructionist approach to participation. We focus on the research interview, where most participant data are elicited and collected in qualitative research projects. Discourse-based interviews involve showing the participants actual pieces of their own writing and asking them to account for their linguistic choices (Odell et al., 1983). This grants the researcher access to important inside lay users’ accounts, and it even allows them to tap into their subconscious. Discourse-based interviews stem from the constructionist school of thought.

Constructionism entails viewing participation and the interview as social interaction i. e. as a dialogic process through which the interviewer and the interviewee actively co-construct their accounts. Reality is not objectively defined but negotiated between participants in the interaction. From a social constructionist perspective, neither is the interviewer an invisible neutral being scientifically extracting the “subject’s truth” nor is the interviewee “the missing respondent” from an interview entirely based on the interviewer’s experience (Warren, 2012, p. 130-131). Both parties engage in an active, dynamic, and reciprocal negotiation of simple and more complex accounts that lead to a historically and contextually bound shared story (Fontana & Frey, 2005). This ultimately entails the building of a relationship of trust and collaboration, which is often slow, emotional, changing, and unpredictable (Johnson & Rowlands, 2012). It involves being open to experiences “beyond anything that a research agenda anticipates” (Atkinson, 2012, p. 123), digressions, disruptions, and possible misunderstandings or breakage of trust.

Despite the well-established value of constructionism in the linguistics literature, it gained momentum during the recent debate on the role of interviews in an “interview society”, in which interviews are pervasive (Atkinson & Silverman, 1997). In the interview society, respondents’ experiences and perceptions are perceived as authentic and truthful, characterizations associated with the quantitative paradigm and a purist stance. The debate centers on whether it is necessary to engage in detailed discourse analysis (Hammersley, 2021). Moving away from the polarity emanating from such debates and adopting a pragmatist stance, we suggest that the quality of interview research can be much improved by adopting a critical and reflexive attitude, paying attention to the how, when, and by whom the accounts are produced (for specific guidelines, see Charmaz, 2015 and Silverman, 2017). This involves understanding that both parties are contextually bound to both prior social knowledge and their temporal roles during the interview (Warren, 2012). The interviewer, on the one hand, can be an experienced or novice researcher with his/her own agenda accountable to funding bodies and collaborators, and the interviewee can be more or less hesitant or talkative with his/her own expectations from the encounter (Atkinson, 2012; Warren, 2012). We agree with Blakely and Moles (2017) that interviews represent liminal moments and a partial picture of reality similar to other research tools and methods.

Further, within a constructionist perspective, we employ an interactional sociolinguistic approach to the analysis of the interview encounter. IS treats encounters as a reflexive process, where everything said relates to the preceding talk reflecting both current and past circumstances. “To engage in verbal communication therefore is not just to express one’s thoughts” (Gumperz, 2015, p. 315). Through this lens, we view the interview as an event where both interactants adopt and alternate a multitude of roles. These range from their situational interviewer-participant roles to the ones that preexisted the event (e.g. researcher - company manager) as well as other types of roles they deem relevant and important such as those of friends, fellow colleagues, or researchers to indicate bonding and collegiality. In the interaction, these roles may conflict, mix, and overlap to the point of becoming indistinct and, by doing so, lead to simple and more complex accounts and digressions from the topic at hand.

3. First and second order accounts

For quite some time research has pointed to a distinction between the layperson’s use of language and the researcher’s reading of it, later known as first and second order accounts of an event. Back in 1953, Schutz highlighted the difference between lay people's and social scientists’ reports. He characterized the latter as “constructs of the constructs made by the actors on the social scene whose behavior the scientist observes and tries to explain in accordance with the procedural rules of his science” (p. 3). According to this view, the lay person first forms his/her subjective common sense of his/her everyday world, which then forms the basis on which the analyst builds his/her own objective theorization, an elaboration of the first. The lay person is unable to theorize but has access to inside mundane knowledge, which is inaccessible and important for the analyst. The latter is portrayed as a scientist, who, as a neutral outsider, can construct theories objectively based on a subjective perception of the world.

The two positions are incompatible with each other and ultimately reflect a top-down approach to doing research; the social scientist first establishes ‘’the problem’’, which then determines what is relevant for its ‘’solution’’ (Schutz, 1953, p. 29).

For a long time, sociolinguistic inquiry has been preoccupied with the importance of highlighting participants’ views along with the complexity of capturing them whether welcoming or demonizing the influence of the researcher. For instance, researchers on politeness theory (e. g. Eelen, 2001) and pragmatics (e. g. Haugh, 2012) have pointed out the problematic relation between the analyst and the participant perspectives. This divide becomes even more pronounced in work highlighting how resistant stereotypical beliefs about language are to change before sociolinguistic evidence (Niedzielski & Preston, 2000), hence the intense yet constructive debate in questioning the two perspectives as binary mutually exclusive entities.

Overall, this duality does not capture the negotiation of the first order report of an event and its second order theorization, which are produced by both researcher and participant in their situated encounter. A participant can produce second order accounts, which can then stir more second order and in turn further first order accounts. As both parties engage in conversation, first order accounts can shift from simple to complex observations and gradually spread into second order theorizations.

As this process unveils various layers of meaning, it often leads to the development of shared meta-talk between them, which, in turn, leads to more theorization

4. Research questions

In this paper, we address the following research questions:

RQ1. How can first and second order accounts contribute to a multi-layered analysis of discourse-based interviews?

RQ2. How can interactional sociolinguistic methodology inform participatory research?

5. Methodology

As an illustration of systematically looking into participatory research, we draw on our larger ongoing mixed methods research on workplace writing and the enactment of formality in workplace emails in 5 MNCs in Greece (Angouri & Machili, 2020, 2022; Machili, 2014; Machili et al., 2019). We allocated control over the collection of emails to the employees who became co-researchers (Holmes & Stubbe, 2015). Due to the problems in access to communication data in business settings, a convenience sampling approach was adopted, which resulted in sampling a range of employees in different hierarchical positions, professional roles, and companies. The interview data were collected from 18 semi-structured discourse-based interviews, where the participants identified the degrees of formality present in their own writing and the reasons behind their use. All interviewees gave their consent to use their emails and were assigned pseudonyms to protect their identities.

For the purposes of this paper, we conduct interactional sociolinguistic analysis of one illustrative excerpt from an interview conducted in 2019 between the researcher and Chris, as participant. Chris was the Chief Financial Officer (CFO) of a large MNC distributing medical equipment in hospitals in Greece. The meeting was held in the participant’s office in the morning, following an appointment. The intention behind the choice of this extract is to illustrate the dynamic, highly interactive nature of the researcher-participant relationship in co-constructing their accounts. In particular, the extract shows how the two parties (the researcher and the participant) enact three types of roles: their pre-existing roles (the first party as academic researcher and the latter as CFO), their respective situated roles (as interviewer and interviewee), and their social roles (as fellow researchers). Through this enactment, we show the co-construction of first and second order accounts. We present the analysis of the excerpt in four parts and highlight first order accounts in light gray and second order in dark gray to enhance their comprehension and identification. For transcription symbols, see Appendix.

6. Analysis of Interview Excerpt

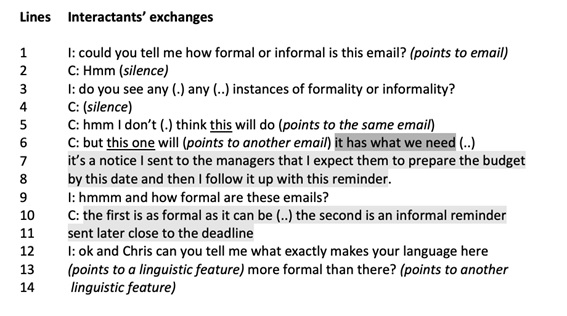

As part 1 in Figure 1 shows, the exchange starts with what initially appears to be a linear question-answer format (Dörnyei, 2007), with both parties in their situated interviewer-participant roles (lines 1-14). The interviewer asks questions about the formality of specific emails (lines 1, 3, 9, 12-13), and Chris, as participant, identifies the degree of formality and explains the context behind their use (lines 7-8, 10-11). These comprise first order accounts.

However, despite the first two questions about a specific email (lines 1, 3), Chris refuses to respond by being silent and chooses another email to discuss, justifying his choice. As Warren (2012) claims, silences in an interview are powerful interactional tools, which can be strategically used to take over control of the interaction (Viruru & Cannella, 2006). Here, both the refusal and the silence signify a disruption to the traditional question-answer format and a strong claim for the lead.

Similarly deviant from the traditional interview concept is Chris’ follow-up explanation in “it has what we need” (line 6). The email’s evaluation for relevance and appropriacy comprises a second order account that is neither triggered by the interviewer, as traditionally expected, nor generates first order accounts, in accordance with linear binary ideals of scientific theory making. As such, the participant’s actions are a clear divergence from Schutz’ (1953) conception of how layperson and scientific accounts work.

The interviewer appears to allow the participant full freedom to make his own choices on which data to discuss (Johnson & Rowlands, 2012) with no interruptions and/or additions of her own, in line with a hands-off approach to data collection (Holmes & Stubbe, 2015).

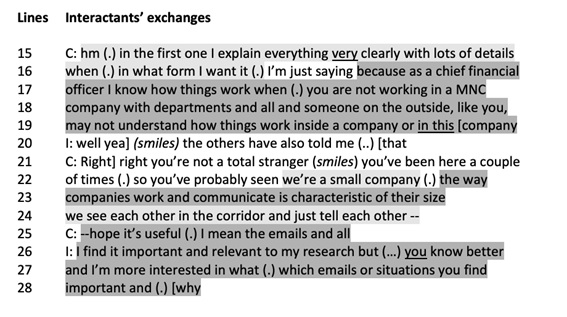

In the second part of the excerpt (lines 15-28), the parties shift to their pre-existing roles of academic researcher - CFO. We see the interview being framed by the prior circumstances that brought both parties to the encounter (Warren, 2012). Chris follows up his initial first order account (lines 15-16) with an explanation of why his insight as a CFO enables him to better understand how things work inside the company, which may not be clear to someone on the outside (lines 16-19). Diverging from the topic at hand, the formality of emails, Chris engages in meta-talk, a second order account of the importance of inside experiential knowledge.

However, being reminded that the researcher has already been briefed about the company, Chris changes his perception of the researcher as an outsider to one who’s “not a complete stranger” (line 21). Unsure of how much inside knowledge his interlocutor has, the participant engages in a series of accounts that alternate from a simple description of the company size (first order) to a theorization about the relation between company communication and size (second order) and then to mundane details of everyday chit-chat in the corridor (first order) - a divergence from Schutz’ (1953) first/second order theory. In agreement with other studies (Adeagbo, 2021; Britton, 2020), this part also challenges the binary nature of insider/outsider perspectives and presents as them as fluid, overlapping, and negotiable standpoints that interactants adopt to steer their way in the interview.

In the following lines (25-28), the discussion digresses from the main topic of discussion to the relevance and usefulness of these accounts. Second order accounts alternate as Chris hopes his feedback is useful (line 25) and the researcher finds the accounts “important and relevant” (line 26). However, the latter then relegates the responsibility of decision-making to the participant (lines 26-28). Self-disclosing meta-talk where interlocutors admit they are less knowledgeable and entitled to speak has been reported elsewhere (Abel et al., 2006; Rapley, 2012).

Also, the intentional offering of control over data collection to the participant problematizes the binary concepts of powerful/lessness as the lead in the interaction appears to be partially granted from one party to another rather than imposed or claimed. We agree with other researchers who call for a more nuanced discussion of the concept of power and how it is enacted linguistically (Machili et al., 2019; Virkkula-Räisänen, 2010; Warren, 2014). As the exchange shows, this meta-talk is discourse in and through which the researcher and the researched co-construct their accounts for and with each other (Angouri, 2018, p. 8).

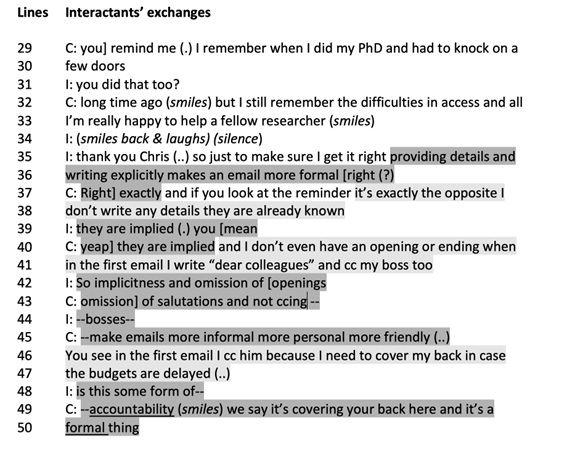

Moving to the third part of the excerpt (lines 29-50), as the parties share similar past experiences, they bond in their social roles as fellow researchers, who reminisce about the difficulties they once encountered in access. This abrupt shift of topic to past recollections of being a researcher is initiated by Chris and triggered by the researcher’s last account about the importance of the participant’s perspective. In their new roles, as fellow researchers, the interactants bond as they express feelings of gratitude and happiness. Chris happily steps into the shoes of his prior role as a researcher and this allows him to find common ground with his fellow interactant, speaking the same language (lines 29-34). In agreement with other researchers, verbal and non-verbal cues such as self-disclosure, smiles, laughter, and silence are seen to lead to bonding and rapport (Abel et al., 2006; Grønnerød, 2004; Rapley, 2012).

It is well known that doing similarity (Fontana & Frey, 2005), along with developing trust and rapport (Tilley et al., 2021), can lead to fruitful territory in an interview (Dörnyei, 2007; Johnson & Rowlands, 2012). Here we highlight that it is part of both parties' constant work “to define and agree on the emergent unfolding trajectory, focus, and meaning of the talk” (Rapley, 2012, p. 545).

Interestingly it is the researcher who seems to take advantage of this bonding and shifts the conversation back to the formality of the emails (line 38) by seeking confirmation of her theory on explicitness (line 36), a second order account. The participant confirms (line 37) and further explains by providing first order details (lines 37-38). These accounts, in turn, lead to another theory on implicitness by the researcher (line 39), which the participant confirms (line 40) and elaborates through first order explanations (lines 40-41). The conversation unfolds as both parties’ second order accounts complement one another (lines 42-50) through disruptions and overlaps of turns, and the occasional addition of first order details for clarification (lines 46-47). Worth noticing is that the theory on accountability is initiated and elaborated further by the participant this time (lines 49-50). Once again, verbal and non-verbal exchanges indicate that simple description and more complex theorization are produced by both parties iteratively, by confirming and supplementing each other. Literature on participatory approaches outside the linguistic fields similarly confirms that participants can participate in the analysis and interpretation of the data (Nind et al., 2016; Rix et al., 2022) by alternating the lead (Seale et al., 2015; Tilley et al., 2021).

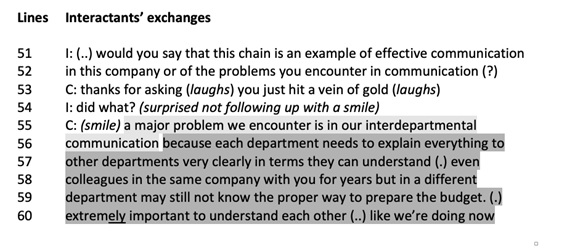

In the last part of the excerpt, the researcher’s question appears to initiate a reversal of the interactants’ roles back to their initial interviewer-interviewee ones (lines 51-60). However, Chris’s reply in “thanks for asking” and joke in “you just hit a vein of gold,” a social yet evaluative comment, appear to place him in a mixed dual role as participant and fellow researcher. The alternation of Chris’ role from participant at the beginning of the extract to manager and next to fellow researcher as well as the respective alternation of the interviewer’s role from interviewer to researcher and then to fellow researcher is far from linear as these roles are momentarily interrupted, mix, overlap and, by doing so, become indistinct and may even trigger potential misreading of intentions. Although the “hitting gold” is intended as a friendly joke, the interviewer’s follow-up question “did what?” and the lack of a smile indicate that it could be perceived as offensive and a cause for a misunderstanding (Grønnerød, 2004).

The detailed explanation that follows (lines 55-60), the laughter, and the retained smile, however, lighten up the atmosphere, and the comment “like we’re doing do now” (line 60) indicates bonding and collegiality. In this way, the prior insider/outsider distinction is eliminated. As fellow researchers, the parties appear to now share inside knowledge, understanding, and language. As this part shows, the interview encounter is highly relational, involving both tensions and bonding. This renders it dynamic, volatile, uncertain, and emergent in the interaction (Johnson & Rowlands, 2012; Rapley, 2012; Rix et al., 2022).

In sum, the excerpt shows a dynamic reciprocal negotiation of temporarily enacted roles and co-constructed first and second order accounts. We see simple description and more complex theorization being produced by both researcher and participant iteratively by confirming and complementing one another. Further, we show that the roles of interviewer/participant, question initiator/respondent, and insider/outsider are fluid and negotiated in situ. The interviewer asks questions and follows her agenda but expresses feelings, shares memories with the participant, and faces potential conflicts. Similarly, the interviewee provides the information requested, but he also refuses to respond, decides on which data to elaborate, digresses off-topic, makes his own evaluative comments, engages in meta-analysis, risks misunderstanding, and bonds. Researcher roles vary from being a total stranger to having some inside company knowledge and to being able to understand the participant very well.

In line with RQ1, the analysis of first and second order accounts highlights the value in viewing the discourse-based interview encounter as social interaction, which is situated, relational, and reciprocal. Participants and researchers are iteratively involved in the co-construction of simple and more complex accounts by drawing on both their prior and present lived experience, their expectations, and the question-answer interview format in their encounter. It means acknowledging the nature of the interview encounter as a messy, uncertain, negotiated space, and considering the interactional conditions of the interview in data analysis.

In line with RQ2, IS can inform participatory research by providing a viable methodology for the analysis of the situated interview encounter. Its contribution highlights drawing attention to more nuanced approaches and moving away from binary thinking. In this way, we can better understand how control over the research process is negotiated in situ. Our analysis indicates that first and second order accounts complement and lead into each other strategically rather than canonically as both researcher and participant take the floor. This ultimately has implications for the ideals of a purely egalitarian relationship between the researcher and the researched collaborating on equal ground.

7. Final Considerations

Admittedly analyzing interview excerpts like the one above qualitatively entails not offering generalizable findings because of the specific context in which they occur. As such, this comprises a limitation of our paper. Although this is true, capturing more layers of individual meaning can help us better understand the complexity of building accounts and negotiating roles. It also allows us to challenge the static ideals of equal partnership in the research process.

Evidently demystifying the role of the neutral researcher may present a challenge for numerous practitioners. This is seen in the static oppositions that are still dominant in our fields and the training of future generations of researchers. However, it is a necessary challenge given the dynamic, complex nature of the interview encounter.

To sum up, instead of debating on a binary between purely constructionist and positivist perspectives, we suggest a holistic approach in which the researcher’s understanding of the phenomenon shifts through the interaction with the participant. We invite future debates on how best to explore the dynamics of this special relationship from fields outside linguistics and on the implications for research methodology developments. Although the interactional approach is well established in linguistics, the consideration of the interactional details of the interview encounter in other fields such as health, business, etc. holds much promise