1.Introduction

At the beginning of the pandemic, it came to the attention of the investigators that as qualitative researchers seeking to apprehend the pertinent educational phenomenon of these momentous times, it would be necessary to conduct multiple case studies. Three such studies were planned, each focusing on a different unit of analysis: distance education in 2020, combined education in 2021, and the return to in-person education in 2022. These represent the three distinctive modalities implemented by the Costa Rican Ministry of Education (MEP, Resolución MEP-003-2022/MS-DM-1001-2022, 2022). Data triangulation was performed for the three single case studies using varied forms such as semi-structured interviews, video recording, document gathering, and photo-elicitation (Elizondo-Mejías et al., 2021; Lopez-Estrada et al., 2022a & 2022b). While collecting data over three consecutive years (2020-2022), the researchers realized that participants often struggled in interviews due to the emotionally charged situations experienced during the pandemic. After extensive reflection, the researchers concluded that a different way to collect data would be helpful, and to this end they settled on body mapping, a technique that was unconventional to the context, but which could elicit information that might be hard to uncover through more conventional means, while providing the participants not only with protagonism, but also a creative, distinctive healing experience.

2.The Study

Data were collected in 2022-2023 for the descriptive case study, Perceptions of the return to face-to-face education in times of pandemic: A case study of five primary English teachers from the Sarapiquí Regional Directorate of Education. The purpose of this study was to describe the experiences of teachers who had worked during distance and combined education regarding the return to in-person education, in order to gain a comprehensive insight into their professional environment and the didactic and pedagogical approaches they employed during the COVID-19 public health crisis.

After the implementation of the distance education modality in 2020 and the intermittent attendance of students to educational centers in 2021, the MEP decided to resume the 2022 academic year with full in-person classes. The primary goal of this was to ensure the student community's safe return to school while implementing educational measures to narrow the educational disparities observed during 2020 and 2021 (Picado, 2022). Since most students in rural areas of Costa Rica were confined to remote learning during the pandemic (Programa Estado de la Nación, 2021), it became imperative to examine the phenomenon of the return to face-to-face school interactions.

The study, in which the Body Mapping technique was used, aimed at answering two research questions: What were the experiences lived by five English teachers in the Educational Directorate of Sarapiquí, Costa Rica while returning to the modality of in-person education? And What were the opinions of five English teachers in the Educational Directorate of Sarapiquí on the process of returning to in-person education?

3. Body Mapping as a Data Collection Technique

Body mapping was first used in 2002 in South Africa as an art therapy method for women living with HIV/AIDS (Devine, 2008; Gastaldo et al, 2012). It has been considered “both a therapeutic technique and research tool that prioritizes the body as a way of exploring knowledge and understanding experience” (Coetzee, 2019, p. 1238). It is a flexible technique that promotes creativity and protagonism on behalf of the participants while seeking to distinguish and represent their constructive experiences and feelings regarding specific social happenings. As a research methodology it seeks to collect information creatively and emphasizes deep reflection processes. More specifically, body mapping involves the creation of body maps using drawing, painting, or other art-based techniques to visually represent aspects of people’s lives, their bodies, and the world they live in (Gastaldo et al., 2012). This technique “enables people to communicate in a meaningful way about their identities and experiences […] through creatively making things themselves, and then reflecting upon what they have made” (Gauntlett & Holzwarth, 2006, p. 82). Body mapping essentially represents a paper-based artistic portrayal of the human body that conveys the experiences, thoughts, feelings, and the environment of the participating individuals with respect to the phenomenon under study (Gastaldo et al., 2012).

Over the years of its use, body mapping has been employed for various purposes including therapy, teamwork, and biographical representations, which have drawn on its ability to communicate stories and processes creatively in a way that stimulates introspection and the creation of meaning. Additionally, it has been used as a method for collecting qualitative data in social sciences, health sciences, artistic research, and more recently, in educational sciences. Its evolution has occurred due to recognition that through this technique, participants can communicate creatively through drawing on deep reflective processes (Gastaldo et al., 2012). It is flexible technique that promotes participants’ empowerment as they focus on the content and meaning that they consider important (Gubrium & Shafer, 2014; Orchard et al., 2014). It generates visually and orally significant qualitative data (Botha, 2017) in a way that gives voice to the participants, validating their own constructivist experiences (Victora & Knauth, 2001), and essentially consists of a visual, narrative, and participatory approach of knowledge construction (Gastaldo et al., 2018).

Skop (2016) suggested that body mapping is an appropriate approach to understanding people's viewpoints and gaining access to their perceptions, as it involves holistically integrating the mind, the body, and the social environment. Depending on their experiences, participants might be uncomfortable or feel challenged when seeking to articulate feelings and opinions about these. This technique seeks to counter such deterrents by encouraging participants to explore the connection between their thoughts, feelings, experiences, and interactions through contemplation of these, which might include difficult states such as pain, discomfort, and frustration, “experiential states” (Skop, 2016, p. 31) that are often hard to put into words. As an alternative to a less prescriptive interviewing style, this technique aims to uncover insights that traditional qualitative methods might overlook, with the ultimate aim of transforming individual experiences into shared collective understanding.

Body mapping, as an innovative technique, allows the participants to concentrate on the data content that is most meaningful to them, while empowering them to express themselves and confirming the authenticity of their experiences (Lys et al., 2018).

3.1 Body Mapping: The Phases

The methodology for this study was adapted from the paper, Body-Map: Storytelling as Research (Gastaldo et al., 2012). As previously mentioned, although body mapping has been used mostly in health and social sciences, intense reflection taking the participants and the context into consideration led the researchers to adapt body mapping for use in this educational study as an ideal way to collect data. The researchers called the session they created, “Body Mapping in an Afternoon”. Participants were invited to attend a 4-hour session, which commenced with a presentation and explanation of the study being undertaken. Researchers went over ethical considerations and participants then signed letters of informed consent before the body mapping technique was finally employed. Participants were always accompanied by either one of the researchers or a research assistant, who provided guidance and support while also taking notes as the participants created their body maps. All materials to be used were supplied and placed in the center of the classroom (Fig. 1). Body mapping occurred in seven phases:

Phase 1: Tracing the maps. Participants were asked to remove their shoes and any extra clothing. They were also asked to think about the posture that best represented them (in terms of who they were, where they worked, and how they felt during the pandemic). They were requested to lie down on a large newsprint paper while one of the research assistants or researchers outlined their bodies. They were asked to think about how they wanted to represent their hands, face, and body parts in general.

Phase 2: Reflecting on distance education. Participants were asked to close their eyes and transport themselves to 2020, commencing with March of that year. They were asked to pay attention to whatever came to their mind during that year, reflecting on the beginning, middle, and end of the year. They were invited to select a color and outline their bodies (writing ED with that color in a corner of the map). They were told to place emphasis on any part of the body that, in some way, represented their feelings or embodied their strengths or their weaknesses during the distance learning process. They were also required to draw or design a symbol, as well as a personal slogan (for example: a phrase, a saying, a song, a prayer) that described their personal and professional experiences during 2020.

Phase 3: Reflecting on combined education. Participants were asked to close their eyes and transport themselves to 2021, commencing with February of that year. They were asked to pay attention to whatever came to their mind during that year, reflecting on the beginning, middle, and end of the year.

They were invited to select a color and outline their bodies (writing EC with that color in a corner of the map). They were told to place emphasis on any part of the body that in some way represented their feelings or embodied their strengths or weaknesses during the combined education modality. They were also requested to draw or design a symbol, as well as a personal slogan (for example: a phrase, a saying, a song, a prayer) that described their personal and professional experiences during 2021.

Phase 4: Reflecting on in-person education. Participants were asked to close their eyes and transport themselves to 2022, commencing with February of that year. They were asked to pay attention to whatever came to their mind during that year, whatever was meaningful or salient, reflecting on the beginning, middle, and end of the year. They were invited to select a color and outline their bodies (writing RP with that color in a corner of the map). They were told to place emphasis on any part of the body that in some way represented their feelings or embodied their strengths or weaknesses during the process of returning to in-person classes. They were also requested to draw or design a symbol, as well as a personal slogan (for example: a phrase, a saying, a song, a prayer) that described their personal and professional experience during 2022.

During phases 2, 3, and 4, the researchers had some reflective, guiding questions in the form of a script to promote reflection on behalf of the participants. For example, some guiding questions in this phase included: How did you experience the beginning and the closing moments of the 2022 school year during the return to in-person attendance? What feelings and experiences did you have during that period? What was good personally or professionally? What was bad on a personal or professional level? What factors were relevant during that period? What was most impactful to you during that period? Think about colors, drawings, symbols, slogans, or any other materials that can help represent what had most impact on you during the 2022 school year return to in-person classes.

Phase 5: Final details to the body maps: Participants were asked to go over any details on the maps, paying attention to the colors, drawings, symbols, and slogans used, as well as any other materials they used or created.

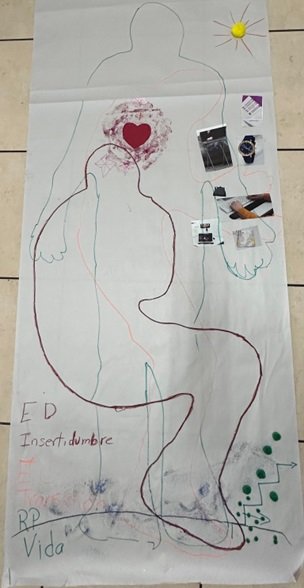

Phase 6: Testimony time (Body map key): The participants were given a sheet to fill out with specific information regarding their maps, for example, the meaning of the colors, the creation of symbols and slogans (Fig. 2). Some guiding questions here included: Why did you choose those colors and not others? What does each color represent? Why did you create these slogans and not others? What does each slogan represent? Why did you emphasize that part of the body and not others? What does each silhouette represent? Do you have any details that should be noted and explained in depth?

Step 7: Final reflections. Participants gathered to talk about the body maps and the experience of creating them.

To illustrate the technique used, although instructed to create a single body map, one of the participants decided to create three body maps on one piece of paper, as seen in Figure 3. The participant did this by delineating the three years representing the three different educational modalities used (2020, 2021, and 2022). He decided to focus on evidencing growth through the modalities, showing how he grew each year, leading to a final awakening once he returned to face-to-face interactions within his context (in the school and with his students.) For 2023, the participant represented a teacher who was grounded and alive (the slogan for 2002 was vida, “life” in English). The participant reflected on how “life” is the time in which we grow; life must continue regardless of challenging situations. According to him, life is about learning how to face difficult circumstances with our own coping mechanisms. Meanwhile, the slogan for 2020 was “uncertainty” (incertidumbre in Spanish). He represented his uncertainty arising from not knowing what was going to happen that year. He complemented this in his testimony by further elaborating, “Uncertainty was the feeling that dominated me all the time. I was scared all the time, listening to the news, all the measures we had to follow from the Minister of Health and Education” (DI-5). The participant represented 2021 in the body map as a time of transition. The body part emphasized during 2020 was his heart as a sign of internal strength, as the body part that had to be stronger than the mind. He noted in his testimony that through distance and combined education, he learned to listen more, to be more empathetic, to be resourceful in tackling any situations that might come up. The different body positions he represented in the three maps communicated how human beings are always experiencing obstacles that can become opportunities for growth.

Once the data were collected, data analysis was carried out using the software for qualitative data analysis ATLAS.ti. The analysis consisted of determining themes and categories through content analysis of the data gathered. For this, the two researchers, together with a researcher assistant ensured validity of the process through intense sessions of identification, synthesis, and review of the information and the application of Hatch’s (2002) six major recursive steps: familiarization with the data, coding into meaningful units, category creation, checking of categories, identification of the most prominent categories, and presentation of the contents. The techniques of data triangulation, intercoder reliability, and member checking were used to ensure both research validity and reliability.

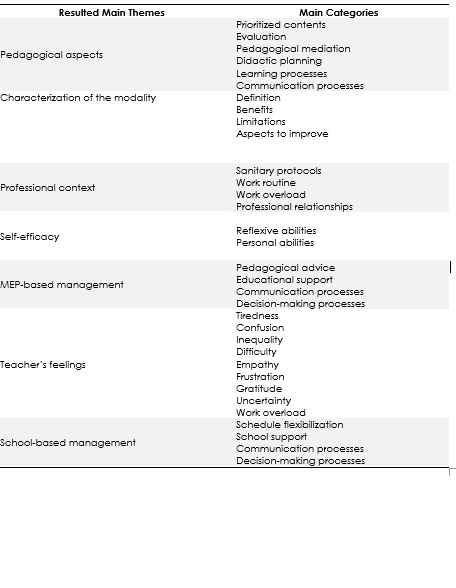

This process resulted in seven themes and a total of 33 categories which semantic relationships were those of strict inclusion and attribution (Spradley, 1979). These themes and categories are portrayed in table 1.

Source: Researcher’s own design

4. Reflections of the Participants and the Researchers

The focus of this paper is not to present the results of the study, but rather to illustrate the technique of body mapping and to share some of the participants’ and the researchers’ insights on its use. The participants commended the technique and viewed it as an insightful and therapeutic activity. One participant stated, “Even though I am no artist, creating the body maps made me feel empowered to express myself artistically, even symbolically… I know it wasn’t a Picasso, but I could express myself. Maybe easier than using my words.” This participant stated how simple it was for him to express himself using this method. Another participant indicated that she found body maps to be “a very nice technique to reflect on everything we experienced during pandemic times. It felt like a therapeutic session, an emotional, kind of psychological therapy session. I really had to look into myself, make connections, really see things as they were. I really liked designing the body maps. I really reflected on how I felt during those times.” The process of creating the body maps was described by all participants as a cathartic experience.

The researchers firmly believe this study demonstrates the successful adaptation of body mapping for use in investigating educational sciences. It represents a valuable method especially for participants who have difficulty expressing their ideas in writing or by speaking, and who through creative processes can express their ideas more clearly. Body mapping is indeed a less directive mechanism than interviewing participants. Taking descriptive notes while the participants were creating the body maps was highly beneficial to analyzing the data. In addition, the reflective guiding questions served as a valuable supplement while the participants were creating their body maps.

Another feature of the success of the application of body mapping in this context was the presence of dedicated researchers and research assistants, one for each participant. This proved advantageous in facilitating individual attention that helped each participant progress at his or her own pace without the pressure of synchronized completion. Researchers and the research assistants alike practiced using the guiding questions before the session to ensure these assisted the participants in reflecting on their experiences and how to represent these in their body maps. Having the participants write their testimonies after each modality was fundamental to activating the knowledge acquired and pushing them to capture more details when reflecting on their body maps. The participants completed three testimonies, one for each modality. These immediate testimonies elicited detailed information from the participants, benefiting from the freshness of their memories after creating body maps for each year (2020, 2021, and 2022).

The most important lesson learned by the researchers is that meticulous planning is essential. Researchers must gather the necessary materials, secure a spacious and safe venue, establish rapport with the participants, explain the methodology clearly, and maintain a supportive presence throughout the entire process.

5. Final Considerations

Body mapping as a technique must be carefully examined to determine whether it can be implemented in a specific study. Even though its usage has been greatest in qualitative studies dealing with health matters, its careful implementation in other studies can be highly beneficial. Qualitative researchers are encouraged to be creative, innovative, disruptive, and flexible in designing their studies. There are tangible limitations to this technique, but fully apprehending how it works and employing it successfully can lead to remarkable benefits for the study itself and for the participants. Flexibility should be employed not only in designing the study, but also in dealing with the participants. In our case, given mobility limitations that prevented a participant from lying down, she instead decided to outline her body in a sitting position, which she then concluded was also the most genuine way to portray her experience during the pandemic, as she had to spend all her time sitting down. Participants’ physical limitations should always be catered for, which will lead to richer, more personalized results.

Other studies conducted using body maps have required several sessions to collect the data. In our case, time was a limitation for our teacher participants, so it was decided to do body mapping in a single afternoon session. This meant the researchers had to make the best of four hours in a way that genuinely collected the qualitative data required without being rushed. Even so, it should be noted that using this technique takes time, more so than do simple interviews.

Additionally, time is required to collect materials, get snacks and “thank you” gifts for the participants, and to ensure the activity is brought to a satisfactory conclusion. Establishing rapport with the participants is fundamental, as is making the participants feel comfortable and welcome in a culturally appropriate fashion (for example, providing them with high quality coffee in the Costa Rican setting). It is necessary to give each participant the time and space they require; in other words, researchers cannot expect every participant to go at the same pace.

Finally, the researchers also reflected on the role that they played as outsiders in the process. They must be careful not to interfere, but instead maintain their objectivity; thus, they must stand back and ask the right questions in a way that guides the creation of the body maps, rather than giving ideas as to their creation.

Taking all these factors into account, body mapping was demonstrated to be a highly valuable technique for qualitative data collection for research examining social phenomena. It can elicit a wealth of data on emotions and experiences that might not be easy to uncover via simple interviews or other more commonly employed techniques and could be more widely employed to enrich the results of a wide range of fields investigating social phenomena.