1.Introduction

Traditional Portuguese Music is often not included in the formal teaching of conservatories and academies in Portugal (Alves, 2016; Domingues, 2022), and not commonly used in instrumental learning, particularly in the violin (Domingues, 2022). Furthermore, when music teachers do use Traditional Portuguese Music in music classes, the approach used in its transmission and study usually follows the formal teaching parameters, which involve reading the score rather than learning by ear and imitation.

In fact, there is limited research on the use of Traditional Portuguese Music in the classroom (Alves, 2016; Santos, 2022; Domingues, 2022), as well as the informal learning practices that are associated with it (Ferreira & Vieira, 2013). Moreover, Green (2000) claims that there is limited research on the attitudes and values of popular musicians and how these factors may impact the learning process (Green, 2000). The author argues that while it is important to include popular music in the curriculum and bring it into the classroom, it is equally important to consider its learning practices, values, and attitudes. This perspective could provide a more comprehensive education that might contribute to the preservation of the cultural heritage of each region, such as the Azores.

With these ideals in mind, during the Supervised Teaching Practice that took place at the CRPD, in São Miguel Island, a project was implemented, focusing on the teaching of traditional Azorean songs, using informal learning practices, and presenting them in a concert together with the Viola da Terra2 students (Sousa, 2022). At the same time, research was carried out aiming to assess the implications of such intervention.

2.Theoretical Framework

Next, this section will explore what the literature states regarding: 1) informal learning practices; 2) the attitudes and values of popular musicians; and 3) combining formal and informal learning.

Informal Music Learning Practices

Over the last 30 years, several studies have pointed to a greater awareness of important learning situations that occur outside the classroom (Rice, 1985; Bailey & Doubleday, 1990; Eraut, 2000; Malcolm et al., 2003; Sefton-Green & Soep, 2007).

Green (2000) points out that, alongside formal education systems, there are other methods of transmitting and acquiring musical skills and knowledge, which refers to as informal music learning practices. According to the author (Green, 2002), informal musical learning involves a set of practices in which musicians learn autonomously through observation and imitation of other musicians and recordings, often with the help or encouragement of family and/or peers.

In agreement, D'Amore (2009) lists five basic principles that summarize informal musical learning practices:

Learning music that students choose, like and identify with.

Learning by ear and by imitation.

Learning together with colleagues and friends.

Acquiring skills and knowledge in a personal way.

Maintaining an interconnection between listening, performing, improvising, and composing.

According to Green (2002), peer and group learning are essential elements of informal music learning practices. This process involves forming musical groups from an early age, exchanging creative building blocks such as chords or scales, and refining improvisational and compositional ideas through group negotiation. It also includes observing other musicians during performances or rehearsals, exchanging advice and technical tips, discussing theoretical information, and talking about music in general.

Attitudes and Values of Popular Musicians

In addition to analysing learning practices related to the acquisition of skills and knowledge of musical performance and technique, Green’s investigation (2002) emphasizes the attitudes and values associated with this process. The researcher states that the learning practices of popular musicians are more instinctive and spontaneous than those of musicians from formal education contexts. She also notes that this type of learning is closer aligned with a child's natural development of the mother tongue and is heavily influenced by their cultural experiences.

In her research, Green (2002) found that popular musicians expressed not only enjoyment but also a clear feeling of love and passion for music. The author inferred that the most important values to these musicians can be broadly categorised into two groups: the first relates to performance and creativity, where technical skills are respected but the most crucial aspect is the feeling; the second refer to personal and emotional aspects, such as cooperation, trust, tolerance, shared musical tastes and passion for music.

Combining Formal and Informal Learning

Feichas (2010) argues that formal and informal learning involve the transmission of specific skills and knowledge, and that both have their own conflicts, advantages, and disadvantages. These differences are reflected in the needs, strengths, and weaknesses of students in each learning context.

Although there is a distinction between formal and informal learning, they are not separate spheres, can overlap, and should not be viewed as opposites (Green, 2000; Folkestad, 2006). In fact, in most learning situations, both types of learning are present and interact simultaneously, even at different levels (Folkestad, 2006).

On this matter, Feichas (2010) argues that pedagogical approaches based on informal learning practices can contribute to valuing musical skills and knowledge, respecting different levels of development, and opening musical conceptions. This author states that this approach values all musical genres equally, minimizes the Eurocentric view and increases levels of motivation. Therefore, this pedagogy of integration can also be seen as a pedagogy of diversity and inclusion.

3. Project and Study Objectives

This article presents an Educational Project that aimed to highlight and investigate the educational and identity potential of Traditional Azorean Music, as well as the learning dimensions and practices inherent to it, in formal violin teaching, at the CRPD.

To this end, an intervention was planned and implemented focusing on the learning of songs from the Azorean Traditional Music, using informal teaching strategies and presenting them in a public performance. At the same time, a qualitative study was conducted to analyse the effects of such intervention and answer the following research questions:

What are the implications of implementing informal music learning practices and using Traditional Azorean Music for students' musical development and identity?

What is the feasibility of combining formal and informal learning practices in violin teaching at the CRPD?

What implications could the inclusion of Azorean Traditional Music and its practices in formal teaching at the CRPD have for the preservation of regional cultural identity?

Additionally, it sought to know about the practices and perceptions of a group of anonymous violin teachers regarding the possible inclusion of Portuguese Traditional Music in violin classes and the informal strategies usually associated with it.

4. Description of the Research Project

The challenges empirically identified, and the literature review led to the implementation of an action research methodology. As such, an intervention and an investigation were planned, as described below.

4.1. Intervention Methodology

The project was implemented as follows:

1) by selecting and adapting the repertoire

2) by providing guided listening sessions of Traditional Azorean Music

3) by the work developed in and out of class

4) by the preparation and presentation of a public performance

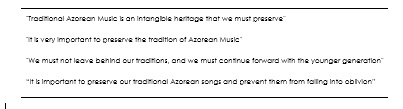

As such, the songs «Mané Chiné» (Pico Island); «Chamarrita» (São Miguel Island); «Canção de Embalar» (Popular); and «Sol Baixo» (Santa Maria Island) were selected and adapted to each student's learning level. Two examples of these songs can be seen in figure 1.

Figure 1 «Sol Baixo» or «Sol Baixinho» (Santa Maria Island) and «Chamarrita» (São Miguel Island) Transcriptions by Carlos Sousa

Concerning the work carried out in the classroom, students were first introduced to Traditional Azorean Music through guided listening to recordings and videos. Subsequently, an aural analysis of the songs was made, in which those songs were divided into smaller sections according to their structure. After this, each student was asked to reproduce each of the different parts with their voice and then with the violin. This process was always carried out without using sheet music.

After learning the melodies, the students were guided to improvise complementary voices and accompaniments to the main melody.

In addition to classroom work, there was constant interaction with students through digital platforms, that allowed for exchanging impressions, requesting assignments, sending explanatory videos, and receiving feedback on student progress.

For the preparation of the concert, the students rehearsed with the Viola da Terra students and their teacher. All participants, including students and teachers, performed in the concert. The performance was heartfelt and provided a beautiful moment of exchange with the community. The atmosphere on stage was relaxed, and everyone sang, played, and improvised together.

4.2. Research Methodology

In addition to the intervention described above, an investigation was conducted to thoroughly evaluate the impact of the implementation of the Project.

The participants in the Study were 7 students of the CRPD, 3 students’ parents, 16 members of the audience present at the performance, and 27 violin teachers. The fieldwork took place between November 2021 and May 2022.

This research project follows a qualitative paradigm and uses data collection methods such as observation and interviews, which, according to Bogdan and Biklen (1994), are representative of this type of research. In accordance, the literature defines qualitative research as a collection of reliable and systematic information on specific aspects of social reality using empirical procedures (Afonso, 2005).

Thus, the data were collected through direct observation with field notes, audiovisual recordings, semi-structured interviews, and anonymous questionnaires.

In this study, direct observation with field notes was used as a complementary method to gather data. Afonso (2005) proposes that direct observation is a reliable and useful method for collecting data. Field notes were systematically done, since they are identified as an advantageous resource for gathering information (Máximo-Esteves, 2008). Direct observation with field notes was conducted during 13 violin classes (45 minutes each), 8 rehearsals (during classes and outside of them), and the public performance. These events - the ones directly involved in the project - were video recorded, making a total of 8 hours of recording. The aim of such observation was to register students' spontaneous reactions and processes, and additionally, to document the reactions of the teachers involved. At the same time, the researcher wrote down interpretative notes, ideas, questions, feelings, and other impressions that arose during observation.

According to Afonso (2005), semi-structured interviews enable a better perception of individual differences, flexibility in time management, diversification in the approach to topics and adaptation to the interviewee. Máximo-Esteves (2008) suggests that this interview model allows interviewees to express their knowledge and opinions on the topic, while the researcher clarifies their responses during the interview. In this case, as the participants were all children, the format of the interview proved to be effective. As such, 7 students aged between 9 and 14 years old were interviewed using the script of questions for both the active group of 3 students, and for the control group (CG) of 4. These interviews were conducted with the students to obtain their opinions and perceptions about the Project, Azorean Traditional Music, and the learning process in the violin classes. The script of questions is presented next.

As we can see int table 1, the questions were the same for the active group and control group (CG), except for the questions 6, 9, 10 and 11.

The selection of the students was based on practical factors, as the active group included students whose lessons were observed and assisted as part of the Supervised Teaching Practice, while the control group included students whose lessons were observed without direct participation. All of them belonged to the class of the collaborating teacher in the CRPD.

Regarding questionnaires, literature show that it is a useful method for collecting qualitative data (Somek & Lewin, 2005; Fonseca, 2014). Almeida and Pinto (1995) state that the advantages of questionnaires include the ability to reach many people, ensure anonymity, and allow respondents to answer at their convenience time, avoiding direct influence from the questioner. These characteristics support the selection of this methodology, ensuring the collection of anonymous and unbiased opinions from three distinct groups: 1) 3 parents of the active group of students; 2) 16 members of the audience at the public performance; and 3) 27 violin teachers.

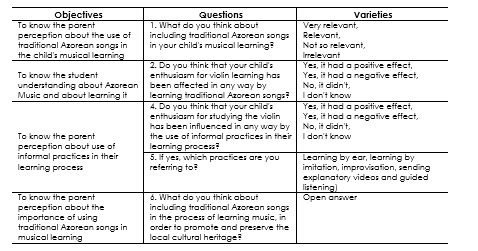

In the table 2, we can see the questions presented to the parents and its objectives.

As we can see above, the questionnaires for the parents were done to get their perceptions and feelings about the impact of the project on their children.

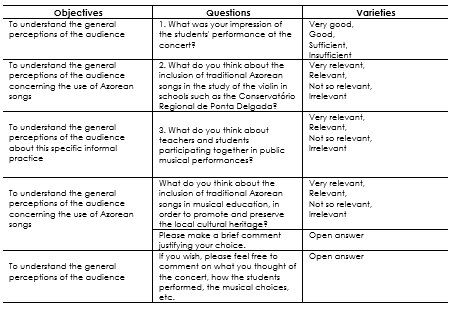

The following table shows the questionnaire for the audience.

Concerning the public performance, about 30 people were present in the audience, who were invited to engage on the study, and 16 answers were obtained.

The questionnaires for the public were distributed and collected in paper and digital formats at the end of the concert.

A more comprehensive questionnaire was prepared for violin teachers. The first section was prepared to know general information about each respondent: age, teaching experience, academic qualifications, and informal musical experiences. Concerning this last point, they were specifically asked about the experience of joining a band, composing or creating original arrangements of different types of music, joining a folk or traditional music group, being part of an academic “tuna” (musical group composed of university students), joining a jazz group, improvising in a concert context, improvising in a rehearsal context, joining a world music group, performing in fado houses (fado is a traditional Portuguese style), singing extempore duel songs and other options (open answer). The respondents could choose different options.

Next, in the table 4, it is presented the questions of the questionnaire to the violin teachers of the sections 2 and 3, which approached the informal music learning practices and formal violin teaching.

As we can see in the table 4, the questionnaires to the violin teachers were conducted to obtain their opinions and perceptions about the knowledge, personal experience and practice about the informal practices in teaching the violin.

The questionnaires for the students’ parents and the 27 violin teachers were made available on the Google Forms platform and shared through a link. The strategy used to choose the 27 teachers in this study is called "Intentional sampling" (Robson, 2002, p. 265; Gray, 2004, p. 324). This means that the choice of the participants by the investigator is done according to the profile that considers specific needs of research (Robson, 2002; Yin, 2011). In this case, teachers working in Portugal, representing the broadest possible perspective of ages, levels of education taught, years of experience and geographical locations (Yin, 2011).

4.2.1. Data Analysis

The principal investigator compiled the gathered information - through semi-structured interviews, anonymous questionnaires, direct observation with field notes, audiovisual recordings - and carried out the content analysis.

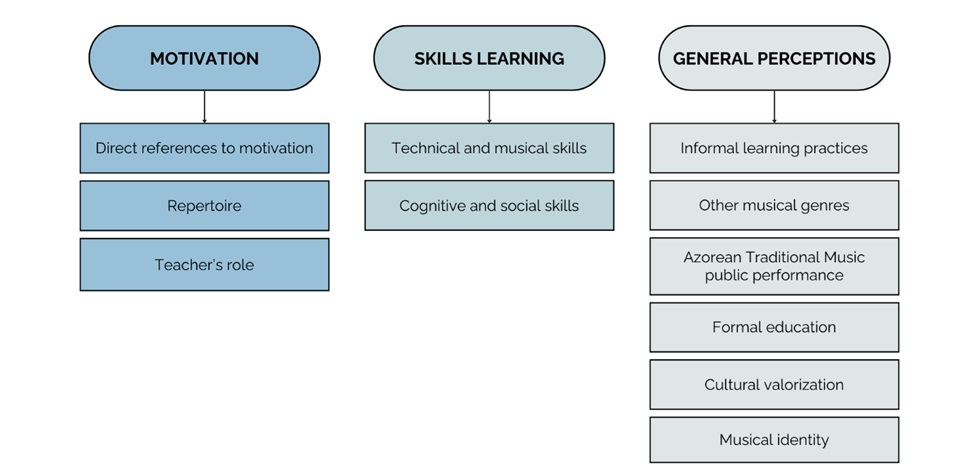

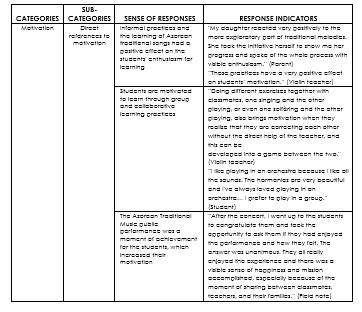

The audiovisual recordings were transcribed, and the written information was organised into categories and sub-categories, from which response indicators were drawn, and the respective response meanings were interpreted. The analysis revealed three main categories: Motivation, Skills Learning and General Perceptions. Each category had its own sub-categories, as shown below in figure 3.

As an example, the table 5 shows an excerpt of the analysis grids, concerning the first category and sub-category presented in the figure 3, and the sense of responses and responses indicators.

The same process was done with all data, which lead to the results presented below.

5. Results

The results suggest that the inclusion of Azorean Traditional Music into CRPD's violin classes, using informal learning practices, had a positive impact on the students' motivation and enhanced the development of their technical, musical, cognitive, and social skills.

Regarding motivation, both the informal practices and the learning of Azorean traditional songs had a positive effect on the students' enthusiasm for learning the violin, as noted by all the parents of the students targeted by the intervention. A parent commented: "My daughter reacted very positively to the more exploratory part of traditional melodies. She took the initiative herself to show me her progress and spoke of the whole process with visible enthusiasm”.

Referring to teacher’s role, the results suggest that it is up to the teacher to establish a connection between the repertoire and the reality of the students, adapting their approach and the repertoire, so that it is apprehended in a significant way. The following statement from a teacher supports this idea: "It is possible to cultivate and support the will to learn. This also involves the role of the teacher when he approaches classical repertoire inspired by popular and traditional music or simply embraces specific proposals from his student".

Concerning the development of technical and musical skills, 24 out of 27 violin teachers stated that the use of informal practices has positive effects on student learning, particularly in terms of motivation, musical and social development. The survey of violin teachers revealed that all of them use or used informal strategies for musical learning in their teaching practice. In total, they mentioned 21 different informal practices. Among the most frequently mentioned strategies were sending video suggestions to students, listening to audios or recordings, performing together with the student, using repertoire outside the official curriculum, and pieces chosen by the student. Composition, improvisation in class, and learning by ear were also mentioned.

The analysis of data indicates that learning by ear and imitation from a teacher or recordings are effective learning strategies. According to one violin teacher, “improving aural skills is a challenging task, so good imitation and improvisation games can help the student to concentrate solely on the instrument and temporarily put the score aside”. Likewise, one of the students involved said: "We focus a lot more on the music. It's not just looking at the paper and seeing what's there. It's listening, it's completely different".

Similarly, the data points to improvisation as an important practice for the technical and creative exploration of the instrument by the students. For instance, a teacher said: "the instrument curriculum tended to abandon the stimulus of improvisation. It is necessary to resort to this experimentation, to know the results that may come from it. I believe that this path can give students space to open horizons and explore their idiosyncrasies in a healthy way".

As far as cognitive and social skills are concerned, the data seems to indicate that informal learning practices enhance student’s cognitive and social development. One violin teacher said: "The effects are very wide-ranging: the development of the ability to analyse and consciously interpret the repertoire played; memorization tools; the development of autonomy and responsibility in individual study; the motivation to discover more about the versatility of their musical instrument, as well as broadening their musical horizons."

Regarding perceptions about informal learning practices, the results show that introducing such practices into formal education leads to a more holistic education. This can be seen in the following statements from two violin teachers: “The practices (…) will certainly result in a training framework that is more favorable to each student's different expectations of instrumental teaching” and “I believe that a balance between the two [practices] should be struck in order to train more versatile and well-rounded violinists”.

Concerning formal education, the data indicate that the official school program should be broadened to encompass a wider range of musical genres and languages. One violin teacher affirmed: “Limiting students to only one genre can hinder their growth. Without this limitation, students gain the ability to adapt to each musical genre and later to each context in the professional environment”. One person of the audience says: "It makes perfect sense to include traditional songs in the conservatory curriculum”.

Regarding cultural valorization, the data seems to point a warning: Portuguese schools and teachers must value and preserve the musical heritage of each region. As one teacher puts it, "We will also have the mission of recreating, creating and preserving musical traditions that are part of our social genetics, otherwise they will be lost irreversibly".

Still concerning cultural valorization, the data obtained indicate that the audience, the parents of the students and the teachers involved in the intervention defend the preservation of Azorean Traditional Music and its inclusion in formal teaching in the CRPD. Several testimonies from the audience support this need, as it can be seen in Table 6.

In fact, regarding the preservation of Azorean Traditional Music and the need to include it in the CRPD formal teaching, the public opinion is fully in agreement, as all respondents stated that the inclusion of traditional Azorean songs in music education is highly relevant for the dissemination and preservation of local cultural heritage.

It is also worth pointing out the following opinion, expressed by the violin teacher whose students were directly involved in the Project: “I would like to congratulate the researcher on the work she has done. She introduced this repertoire that, unfortunately, we use little and should use more because our songbook is very rich and nowadays children know little about it. It is rarely sung in schools, and we cannot let our tradition and our treasure, which is our songbook, die. I will continue to use this type of repertoire because it is worth it!”

6.Conclusions

The results of this research confirm the problematic presented in the literature, namely the limitations pointed out in formal education, concerning the reduced representation of Traditional Music in formal violin learning, and show, as well, the advantages of using this kind of music in music classes and the informal practices associated with it (Green, 2000; Ferreira & Vieira, 2013; Alves, 2016; Santos, 2022; Domingues, 2022).

The data obtained prove that the Educational Project developed boosted the motivation of the students and allowed them to explore the traditional songs and its practices in a more creative and unhindered way.

Additionally, the implementation of this Project stimulated the development of different skills in the students, particularly their listening, memorization, creative and improvisation skills. The rehearsals and public concert also fostered group learning, discipline, and the ability to concentrate. These findings support Green's argument (2000; 2002) for the benefits of using this type of music in music lessons, and the informal practices associated with it.

Cultural awareness was another key element emphasised in the conception and implementation of this Project. It was clear that the intervention contributed to the enthusiasm of the students and allowed both the teachers involved and the audience to reformulate their perceptions about learning the violin at the CRPD and its relationship with Azorean Traditional Music. Likewise, the intervention successfully raised awareness among the participating teachers, who expressed a desire to continue with similar initiatives. Thus, the Project proved to be an effective means of disseminating, valuing, and preserving the regional musical heritage and its practices.

As such, the teaching approach proposed in this Project highlights the important role that schools and teachers play in introducing children and young people to their local musical context, while also preserving and valuing the traditional music from the region. The intervention and research show that, by carefully observing our cultural heritage, we can create a unique and informed approach to teaching.

It is important to note that this work did not intend to discredit formal education and its practices. In fact, this research highlights the benefits of formal teaching while also acknowledging its limitations, from a more eclectic and inclusive perspective.

In this sense, the conclusions of this research lead us to believe that formal teaching should allow and encourage its combination with informal learning practices (Green, 2000; 2002; Feichas, 2010). If there is flexibility and receptiveness, as well as a greater awareness of the student's social context and reality, the learning process will be more varied, meaningful, effective, and complete. This approach, when combined with an appreciation of the cultural heritage of traditional music, makes the process more diverse, relevant, and inclusive (Feichas, 2010).

This investigation emphasizes the importance of teachers having a comprehensive understanding of their region’s traditional music, as well as other musical genres, and the informal learning practices associated with them (Green, 2000; 2002; Ferreira & Vieira, 2013). This knowledge can improve pedagogical practice and give students more freedom to explore their own pathways.