1. Introduction

Trust and collaboration among human service organizations catalyze the identification and implementation of solutions to complex societal problems (e.g., child welfare, drug overdose, and suicide; Hamer & Mays, 2020). Bryson et al. (2015) defined collaboration across sectors as sharing information, resources, or skills to achieve an outcome that organizations could not accomplish separately. However, in the absence of trust and collaboration, many agencies operate in silos, resulting in ineffectual delivery of services (Kania & Kramer, 2011). Collaborative efforts may fail due to a lack of trust, time, resources, and agency and community support. Further, cross-sector collaboration among human service organizations produces effective outcomes when partners are engaged, trust one another, and have shared goals.

Developing partnerships between university researchers and community service organizations with the objective of program evaluation offers a valuable extension of cross-sector collaboration, including the transferability of evaluative findings. Specifically, there is an opportunity for university researchers with expertise in qualitative methods to share those skills with community providers. Many community service organizations do not have staff with the skills or know-how to conduct research and/or program evaluations (Steele & Rawls, 2015). Increasingly, evaluation is needed to address service gaps and improve service implementation at the community level. For example, while mental health disorders are associated with at least 18% of the global disease burden, few individuals can access evidence-based treatment, and implementing these practices fails frequently (Campion et al., 2022).

Implementing evidence-based programming in community settings requires an iterative process of program evaluation and quality improvement consistent with action research traditions and other qualitative approaches (Metz & Albers, 2014). Developing and maintaining trust throughout this recursive process is necessary to optimize results. University personnel with research design and evaluation expertise are uniquely positioned to fill this need in the public sector (Prosek, 2020). Organizations delivering mental health services to high needs populations can collaborate with university researchers in designing and implementing qualitative program evaluations, ensuring that those most vulnerable have access to empirically supported treatments delivered with fidelity. We argue that trust is essential in guiding effective qualitative program evaluation, especially in iterative, ongoing cross-sector relationships.

2. Objectives

The purpose of this conceptual paper is to highlight the essentiality of trust in qualitative research/program evaluation and propose a conceptual model illustrating the relationship between trustworthiness, trust, and impact in the evaluation process. In addition, we intend to raise awareness of the foundational nature of trust to make a sustained impact in community work with qualitative research/program evaluation by joining together university and community partners. We will provide practical approaches to developing trust in qualitative research/program evaluation.

3. Theoretical Framework

Our approach to community-focused qualitative program evaluation is anchored in community-based participatory research (Wallerstein et al., 2020), use evaluation approach (Patton, 2012), with an action research paradigm (Kemmis & McTaggart, 1988). Consistent with the participatory traditions of action research, our model follows an iterative person-centered research paradigm historically applied to addressing human services problems (Altrichter et al., 2002). Action research's iterative spirals (i.e., planning, acting, observing, and reflecting) apply to intractable multigenerational social issues such as substance use, homelessness, and poverty (Kemmis & McTaggart, 1988).

Action research is defined as a community-based, action science and learning approach often used to improve practice in public health settings (Lingard et al., 2008). Kemmis and McTaggart (1988) proposed a model of action research entitled the action research spiral. Their model consists of process cycles for program evaluation, including (a) planning for a change; (b) acting and observing the process and consequences of the change; (c) reflecting on these processes and consequences; (d) replanning, acting and observing; and (e) reflecting. The model allows for flexibility and overlap of stages. In addition, initial plans may become outdated as new information is gathered through learning experiences.

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is anchored in partnerships between researchers and community stakeholders and includes stakeholders as co-creators of the research. Community stakeholders are considered “experts” in their knowledge base to drive social transformation. Despite some differences in how CBPR is used, one commonality is a commitment to de-centered research “expertise” (Jull et al., 2017). Central to both methodologies is establishing trust among these partnerships as they extend to relationships between university researchers and community partners. Our operational definition of trust is a firm belief in the dependability, ability, or strength of someone or something. Essential components of trust are honesty, reliability, and follow-through.

4. The Impact of Trust in Qualitative Evaluation

4.1 Relationships and Mentorships

Faculty/student mentorships may provide a foundation for university/community partnership through applied research opportunities. Extant literature highlights the importance of these mentorships in student professional development (Anekstein & Vereen, 2018; Borders et al., 2012). A faculty mentor supports student growth by preparing doctoral students to teach, supervise, consult, and conduct trustworthy research. Anekstein and Vereen (2018) proposed several strategies to foster faculty/student research mentorship, including individual and departmental level approaches and a formalized research mentorship program in behavioral health training programs.

Regarding an individual approach, doctoral or master's students could be paired with a trusted faculty mentor early in their program based on similar research interests or work experience (Anekstein & Vereen, 2018), thus allowing the student to engage in multi-year program evaluation projects. Many grant-funded projects are multi-year and require involvement from program evaluators over a longer period (i.e., more than one or two semesters). Establishing a research mentor early in a student's program of study allows for long-term engagement with the program evaluation. Beyond grant-funded projects, applied research in community-based settings offers an opportunity for master's and doctoral students to potentially have internship placements in these settings. Interns may accrue indirect time (i.e., non-clinical hours) through program evaluation activities.

Further, these settings are positioned to serve as sites for a research internship where students can gain valuable experience in applied research in human services settings. An embedded evaluation framework invites the external evaluator to join the participants, delivering the intervention (i.e., counseling or treatment) as a trusted co-owner of the evaluation process. This approach is consistent with a participatory evaluation methodology (Whitmore, 1998). In the traditions of empowerment evaluation (Fetterman & Wandersman, 2005), embedded evaluation aims to improve the program being evaluated by developing the program participants' skills and autonomy (i.e., program staff and stakeholders), all the while engendering a culture, not just of research but of trust. Active involvement of the participants in collecting and analyzing trustworthy qualitative data and then identifying the next steps engages evaluators and participants as trusted co-creators of the evaluation process.

Lastly, university programs and community service agencies should conduct purposeful relationship-building activities. These activities facilitate the development of trust and may include joint training opportunities (e.g., training in evidence-based practice offered to counselors at the agency and counselors-in-training). Counselors and clinical supervisors from these community-based organizations may be invited to speak in university classes at the graduate and undergraduate levels.

4.2 Data Collection

Braithwaite and colleagues (2012) pointed out that some evaluation models historically consisted of a "helicopter evaluator" in which a university faculty researcher arrives in the community to design and collect data and then whisks away to publish papers for their professional gain. Antithetically, like participatory evaluation (and qualitative research in general), embedded evaluation involves the evaluator working alongside community stakeholders as one who views community stakeholders as equals in the program evaluation process (Vella, 2002). The development of trust and relationship-building activities (e.g., evaluators' attendance at team meetings and engagement in professional-social contacts) support an embedded evaluation, drawing from the literature on cross-sector collaboration (Kania & Kramer, 2011; Wolff, 2016). Developing trust is a pathway leading to quality research questions. Some drivers to foster trust include building relationships, sharing values, investing time in the community, and practicing humility. When these key ingredients are in place, good, trustworthy data is a resulting outcome.

Program evaluation in community service organizations offers several implications for qualitative researchers. Firstly, program evaluation focuses on informing stakeholders of accountability findings and guiding programming (Fitzpatrick et al., 2011). Then too, it benefits students by providing them with a unique learning opportunity to publish and present findings from the program evaluation, while simultaneously experiencing the value of trust in the evaluation process. Put another way, partnering with university faculty in preparing publications, conference posters, and presentations offers valuable professional development for students (Anekstein & Vereen, 2018; Prosek, 2020). In addition, these activities can make important contributions to the literature in the counseling, public health, and implementation science fields, highlighting mutually reinforcing activities, a condition for collaboration and trust (Kania & Kramer, 2011).

To build an infrastructure for data collection, university human services programs may wish to formalize trusted relationships with community service organizations for their students to complete research internships, answering the call of previous research to establish formalized faculty/student mentorship programs (Anekstein & Vereen, 2018). For example, memoranda of understanding could be developed to outline the roles and responsibilities of each organization, similar to the agreement signed for a clinical internship in a community-based setting. This design allows students to obtain real-world research experience, much like the real-world experience that a clinical internship offers. In addition, formalized and structured approaches to a university/community partnership may increase the likelihood of these relationships being sustained as students matriculate through their graduate programs.

4.3 Transferability of Results

Lincoln and Guba (1985), perhaps implicitly, introduced the notion of trust to qualitative research by employing the term trustworthiness. For them (i.e., Lincoln & Guba), trustworthiness refers to the minimal criteria needed to ensure, or at least evaluate, the reliability and quality of the qualitative research presented (Schwandt, 2015). More recently, Creswell and Poth (2018) proffered the construct of validity over trustworthiness, defining it as “an attempt to assess the accuracy of the findings as best described by…the readers (or reviewers)” (p. 259).

A significant indicator of trust (or, more accurately, trustworthiness) in qualitative research/evaluation is transferability of results (Creswell & Poth, 2018; Curtin & Fossey 2017; Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Schwandt, 2015). Some (e.g. Schwandt, 2015) loosely equate transferability with generalizability, a term quantitative researchers use, particularly as an indicator of external validity (Curtin & Fossey, 2017). From our perspective, however, transferability is more about application than generalization. Specifically, as qualitative researchers/evaluators, we should provide in our write-up enough rich description and detailed information about the participants, the process, and the findings/results to “...enable the reader to make comparisons with other individuals and groups, to their own experiences or to other research findings” (Curtin & Fosssey, p. 92). Put another way, if we as researchers/evaluators have done our job, the reader should be able to trust our findings enough to see areas where those findings are applicable and transferable.

5. Conceptual Model of Trust in Community-Based Qualitative Program Evaluation

5.1 Our Model

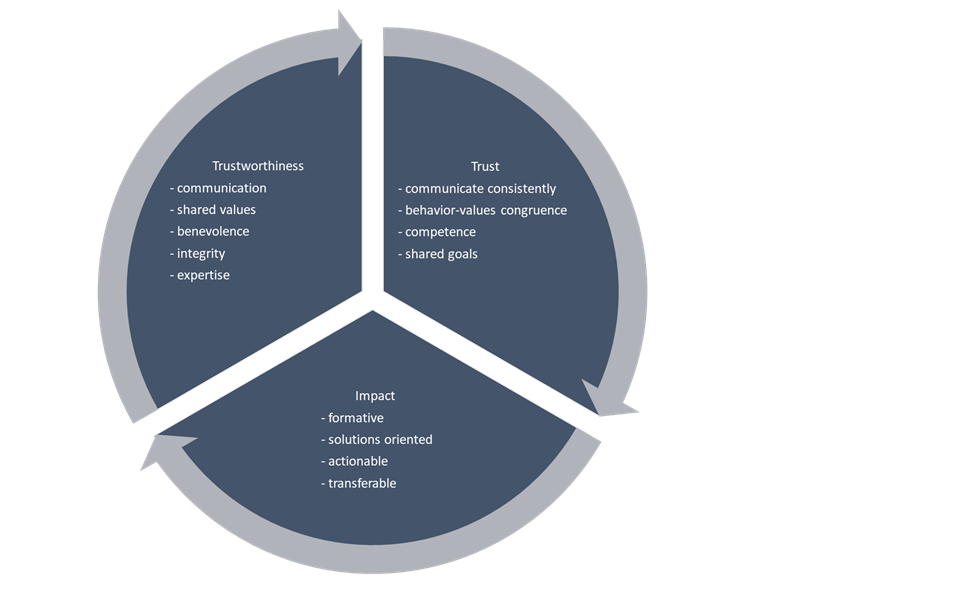

In addition to our experiences (see next section), our model is grounded in three seminal works focusing on trust in business-business relationships (Blois, 1999), organizational trustworthiness as a mediator to both cognitive and affective trust (Sekhon et al., 2014), and relationship stability in inter-organizational reliance (Mouzas et al., 2007). Our model consists of trustworthiness, trust, and impact in a way that we view as iterative. That is, trustworthiness results in trust, which then results in impact, which then results in more trustworthiness, and so on (see Figure 1). In causal sequence terms, trustworthiness is the antecedent, trust is the mediator, and impact is the outcome.

Developing trustworthiness is the first step in establishing a trust relationship. As seen in Figure 1, trustworthiness includes openness in communication, identification of shared values, demonstrated benevolence and concern, integrity, and expertise (Sekhon et al., 2014). Trustworthiness can be a product of presumptions in some other fashion than personal experience (Blois, 1999).

For example, in a university-community collaboration, perceptions of expertise may be presumed by the experiences of evaluators (e.g., teaching relevant course content and scholarly publications) rather than direct experience between the evaluator and the organization. Without prior experience between the evaluation team and the program stakeholders and staff, any presumptions of trustworthiness can be built or undone by the first interactions between the evaluator and the program team. Similar to the qualitative interview, establishing rapport with the program team that provides them a voice in the evaluation process is foundational to developing a productive relationship. Authentically developing relationships with the program team is how the evaluator reveals shared values and demonstrates competency, open bilateral communication, and integrity. In our case, the evaluation team met one-on-one with each of the team leads to understand their concerns and goals.

Delivering on the expectations set at the formation of the university-community evaluation relationship facilitates the journey from trustworthiness to trust. University scholars bring several skills to this partnership, including multimethod research skills, gathering and synthesizing the most relevant literature, developing clear research questions, and optimizing data collection and analysis. Community organizations bring first-hand knowledge of community needs and relevant expertise to meet those needs. When university/community partnerships operate in this carefully designed manner, trust is established, and the opportunity for profound impact increases.

Impact is highly dependent on trust. For example, in our case study, trust in the evaluation team (interviewer and analyst) created a safe space for participants to share openly during the interview process, resulting in higher-quality data. This enabled the evaluation team to generate solutions-oriented and actionable recommendations for the community program. In addition, quality data increases transferability beyond the current case. The university community partnership is reinforced by treating each evaluation cycle as formative.

5.2. Our Model In Action

An accredited counselor education program in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States provides the setting for the case example, highlighting the essentiality of trust. This program offers master’s and doctoral degrees through residential and online programs. The faculty has expertise in both quantitative and qualitative research methods.

I (third author) was recently a third-year local doctoral student in this program. I also worked as a clinical supervisor, project director, and grant writer in a public behavioral health organization. I approached a faculty member in the counselor education program who teaches statistics and research design and invited him to serve as an external evaluator on a federal grant during my first year as a doctoral student (Anekstein & Vereen, 2018). My agency was awarded four-year funding to implement a rural health outreach program using an evidence-based practice to treat adults with serious mental illness. The project required an external evaluator with a specific skill set to provide a robust and meaningful evaluation and reduce potential bias in data collection and analysis (Prosek, 2020).

I was introduced to this evaluator/professor by a mutual colleague several years before I entered the doctoral program.

During the first year of program implementation, the evaluator (second author) and I identified outcome measures for the program. Measurements were embedded in our agency’s electronic health record, and reports were generated and analyzed by the evaluator. Beyond the required descriptive statistics reported to the funder, we developed a qualitative case study evaluation consistent with our embedded evaluation approach. Another professor with expertise in qualitative research (first author) joined our research team, and a qualitative holistic single case study design (Yin, 1984) was conceptualized. By the eighth month of the first year of the grant award, interview guides were developed, and the qualitative researcher began to conduct semistructured individual interviews with project staff to understand the facilitators and barriers of the evidence-based practice implementation. The interviews were professionally transcribed, and the research team followed thematic analysis procedures (Braun & Clarke, 2006), coded the interviews, and identified themes. Themes were member-checked through a participant focus group to increase trustworthiness and support long-term member engagement with the data (Creswell & Poth, 2018). Within ten months of the initial funding start date, our three-person research team published our first manuscript in a peer-reviewed journal on adopting the evidence-based practice. In addition, we received acceptance at two national counseling conferences to present our program evaluation. The values of our team (i.e., curiosity, non-judgmental stance, difference-making, and calling) were consistently aligned throughout our work together.

Driven by the momentum from our rural health outreach project, the university/community collaboration expanded later that year. The behavioral health agency received federal funding to expand the capacity of our drug treatment court, and our evaluation team was asked to partner on the program evaluation. Drawing on our experience and accomplishments from our first project, we approached the second project. We continued refining our program evaluation model and deliverables to meet stakeholder goals. As a result, we have been invited to participate in additional program evaluation projects consistent with our embedded evaluation approach and our shared values to make a difference in our community.

This partnership between a clinical supervisor/project director (third author) in a community behavioral health agency and faculty in behavioral sciences (first and second authors) offered experiential learning opportunities for me in the areas of assessment and outcome measurement (Lenz & Wester, 2017). My skills in both summative and outcome evaluation grew because of the opportunity to work alongside my faculty mentors and develop these trusting relationships. I built upon my counseling and clinical assessment skills with program evaluation by using thoughtful and detailed assessment as a basis for gathering and analyzing data. However, sometimes, I needed to bracket off my identity as a counselor to provide program evaluation. My faculty mentors assisted me in these areas, demonstrating the importance of the research team in triangulating the data (Creswell & Poth, 2018).

More broadly, this collaboration triggered the development of a larger relationship between the community behavioral health organization and the university community, consistent with one area where trust impacts qualitative program evaluation.

This relationship development followed the conditions for collaboration outlined by Kania and Kramer (2011), including common agenda, shared measurement, mutually reinforcing activities, and continuous communication. Our research team met regularly from the outset of our partnership. Our first step was to assess the needs of our project from the perspectives of deliverables to the funder, community stakeholders, and clients served in the project (Prosek, 2020). We held regular meetings to review progress and barriers toward our program evaluation goals and objectives. Using an embedded evaluation approach, both university evaluators attended team meetings and training sessions and regularly interacted with project participants. We found the learning and growth to be bidirectional on our team. The university evaluators used their experience in community behavioral health to provide valuable and tangible examples of program evaluation design to students in their classes. I continued to develop my skills as a researcher and evaluator through my ongoing engagement with these projects and feedback from the university faculty consistent with the importance of trust in data collection. One challenge encountered was buy-in from the community to engage in qualitative program evaluations. Some community members may have felt that the university professors were removed from understanding the needs of vulnerable population due to their academic setting. As a result, specialized efforts were made to develop relationships between the university and community partners. Some of these efforts included values alignment between the sectors. Driven by challenges and opportunities through our collaboration, we offer a conceptual model of trust in our evaluation approach. Our model is iterative, and we continue to add to and revise our approach, consistent with the action research spirals described previously.

6. Discussion

Anchored in trust and marshaled by shared values, our program evaluation model in community behavioral health offers several implications for university behavioral health faculty and community stakeholders. Ideally, program evaluation focuses on informing stakeholders of accountability findings and guiding programming (Fitzpatrick et al., 2011). Trust is a prerequisite to this process. Through our process of qualitative program evaluation, we found that shared values, relationship building, humility, and time investment were associated with evaluation impact, which aligns with use evaluation approaches (Patton, 2012). A benefit and learning opportunity for counselors-in-training, community counselors, and doctoral students is the ability to publish and present findings from the program evaluation. Partnership with a counselor educator in preparing publications, conference posters, and presentations offers valuable professional development for students (Anekstein & Vereen, 2018; Prosek, 2020). In addition, these activities can make important contributions to the literature in the counseling, public health, and implementation science fields, highlighting mutually reinforcing activities, a condition for collaboration (Kania & Kramer, 2011). Further, a partnership can assist community counselors by allowing them to focus on their identity as a counselor. In community settings, counselor identity can be more challenging to maintain, given the multiple demands community-based clinicians face. Humility is present when university faculty and professors are open to learning about community-based programs and public behavioral health.

This humility requires “stepping outside” of the ivory tower of the academy to “the streets” and working alongside agencies serving vulnerable populations (e.g., homelessness, poverty, addiction). This partnership requires an intentional investment of time to earn the trust of these stakeholders.

Some ways to foster trust and relationships include formalizing partnerships. University behavioral health programs may wish to formalize relationships with community organizations for their students to complete research internships, answering the call of previous research to establish formalized faculty/student mentorship programs (Anekstein & Vereen, 2018). For example, memoranda of understanding could be developed to outline the roles and responsibilities of each organization, similar to the agreement signed for a clinical internship in a community-based counseling setting. This design allows students to obtain real-world research experience, much like the real-world experience that a clinical internship offers. In addition, formalized and structured approaches to a university/community partnership may increase the likelihood of these relationships being sustained as students matriculate through their graduate program. Furthermore, students in counselor education programs would have an opportunity to gain expertise in specific research designs such as Yin’s (1984) single holistic case study and Braun and Clarke’s (2006) thematic analysis procedures. This research experience may be leveraged for student dissertations or other research projects, including conference presentations and papers disseminated through peer-reviewed journals. A potential distal benefit of this approach is the possibility of employment at the agency after the student completes their degree. This real-world research experience also increases a student’s employability after graduation across different sectors (e.g., university setting, public health setting). This experience also benefits community-based counselors who are uniquely positioned to engage in applied research in their settings. Exposure to program evaluation may provide counselors with the necessary experience for promotions to supervisory or administrative positions and enhance their professional development.

Counselor education programs and behavioral health agencies should engage in purposeful relationship-building activities. These activities may include joint training opportunities (e.g., training in evidence-based practice offered to counselors at the agency and counselors-in-training). Networking among the university and community can be fostered through engagement in counselor education organizations, such as the local counselors’ association. Counselors and clinical supervisors from the behavioral health organization may be invited to speak in counselor education courses.

When the conditions for trust are met, increased opportunities for immediate and sustained impact are present. Impact is anchored in developing research questions, studious attention to the research literature, a review of available archival data, and a sound plan for data collection.

7. Final Considerations

Building on cross-sector collaboration models (Kania & Kramer, 2011; Wolff, 2016), developing trust in university/community collaboration offers an opportunity for counselors, administrators, and clinical supervisors in public behavioral health to partner with counselor education faculty on program evaluation. When trust is present, these opportunities allow for mutually reinforcing activities and the execution of a shared vision to improve the health and wellness of individuals receiving mental health and substance use counseling and recovery support (Kania & Kramer, 2013). In addition, bidirectional growth and learning can motivate these partnerships to flourish and fill a needed gap in program evaluation when partner take an approach of humilty and invest time in engaging the community. Our argument for university/community partnership development converges with research suggesting counselors are increasing their involvement with outcome evaluation and measurement (Peterson et al., 2020). Trust-based strategies to support these partnerships include faculty engagement in community mental health and substance use coalitions, faculty/student research mentorship, and an embedded evaluation design to foster trust and knowledge sharing (Hamer & Mays, 2020). Key takeaways on the impact of trust include quicker research-to-practice pathways, engagement of participants as co-creators of the evaluation process, and an emphasis on cross-sector collaborative approaches.