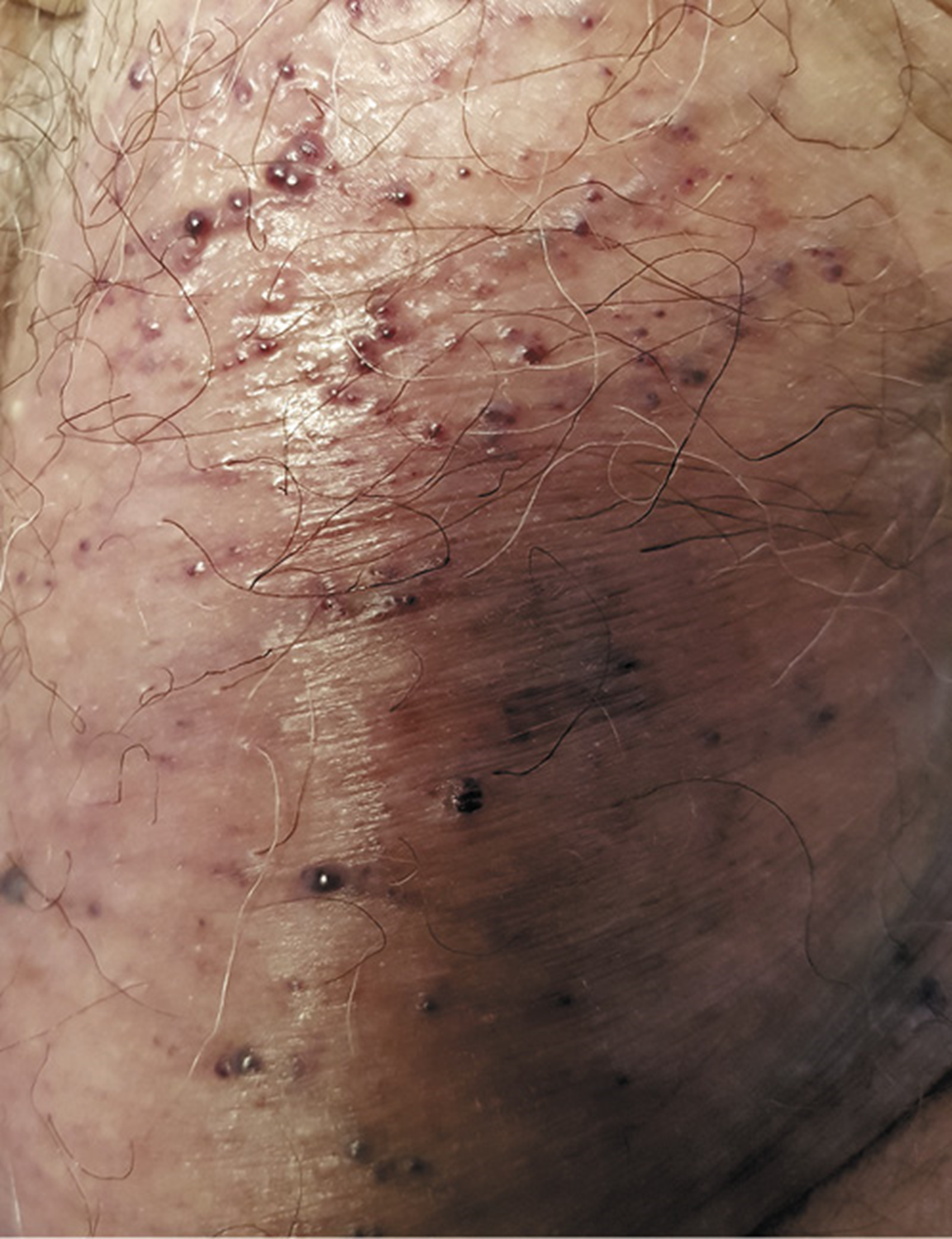

An 80-year-old leukodermic man presented with iron deficiency anemia (hemoglobin 10.4 g/dL; mean corpuscular volume (MCV) 75 fL; serum ferritin 15 ng/mL) His past history included arterial hypertension and atrial fibrillation. Medication history included dabigatran. The patient had no history of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, peptic ulcers, or chronic liver disease. No relevant family history was recorded. He denied having recurrent epistaxis or overt gastrointestinal bleeding. He underwent an esophago-gastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy as part of the workup for iron deficiency anemia; these were unrevealing. He then underwent capsule endoscopy; multiple, protruding, nodular, bluish lesions were found in the small bowel (Fig. 1, 2) without active bleeding. Given the clinical and endoscopic features, his medical records were reviewed, and a previous dermatology appointment was found where multiple, violaceous, compressible, nonpulsatile nodular lesions were described on the skin (Fig. 3). Altogether, given the multifocal, venous vascular malformations, we established a diagnosis of blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome (BRBNS). The patient is currently on oral iron supplementation with a good clinical response (hemoglobin 12.4 g/dL)

BRBNS (or Bean’s disease) is a rare disease mainly characterized by multiple venous malformations that can affect any organ system, but frequently affecting the cutaneous and gastrointestinal systems (1-3). The etiology and pathogenesis remain uncertain (1, 3). The majority of cases are sporadic, although autosomal inheritance has been identified associated with the chromosome 9p (1, 2). The diagnosis is based on the presence of characteristic venous malformations, and up to 87% of patients have multiple organ involvement (1);. Lesions are often present from birth or may develop during childhood; however, 4% of cases present during adulthood (1). The cutaneous lesions are characteristically rubbery, soft, and easily compressible (they promptly refill after compression) (1, 2). Gastrointestinal lesions are mostly found in the small bowel and distal large bowel, and are typically bluish nodules (1, 2). Individuals with gastrointestinal involvement typically present with gastrointestinal bleeding or iron deficiency anemia (1, 2, 4). The treatment of this syndrome is usually conservative and should be guided by the topography of the vascular lesions and disease severity (1, 2, 4). Accordingly, if needed, gastrointestinal lesions can be managed with endoscopic therapy or surgery (1, 2, 4). Cutaneous lesions, on the other hand, generally do not require treatment (1). Finally, systemic medical treatment with antiangiogenic agents like sirolimus have been successfully used as a rescue treatment (1, 5). In this particular case, the beginning of anticoagulation might have been the key for the diagnosis of this late-onset BRBNS since it might have triggered a common manifestation of BRBNS. We emphasize the utmost importance of considering the full medical history as well as a physical examination, in order to provide an adequate endoscopic diagnosis, especially when considering systemic disorders involving the gastrointestinal tract.