Introduction

The diagnostic yield (DY) of small-bowel capsule endoscopy (SBCE) may vary depending on the indication. In obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB), the DY could be as high as 93% in ongoing overt bleeding and as low as 12.9% in previous overt bleeding [1]. Concerning other indications, the DY of SBCE is around 47% in iron-deficiency anemia (IDA) [2], 52% for Crohn’s disease (CD) [3], and 42.9% for diarrhea [4]. Some strategies, e.g., the use of simethicone and prokinetics, have been proposed to increase the diagnostic rate of capsule endoscopy with varying results [5].

There is limited evidence of the usefulness of a second evaluation of SBCE recordings. A study showed that a “back-to-back” evaluation increased the DY of the first from 37.5 to 62.5% [6]. “Back-to-back” in SBCE recordings has been used in other studies to assess DY but using different SBCE platforms [7, 8].

The little evidence that exists seems to show that the second evaluation can increase SBCE performance. The aim of this study is to assess whether a second evaluation of SBCE recordings by another reviewer can increase the DY and improve patient management.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

SBCE (Pillcam SB3; Given Imaging Ltd., Yoqneam, Israel) recordings with different indications, already read by a first endoscopist, were reread by a second blinded endoscopist. When the findings from the 2 revisions were different, the images were discussed by the endoscopists; if they did not reach consensus, they took the opinion of a third endoscopist into account. The first evaluation was considered as the finding of the first endoscopist only, while the second evaluation was considered as the finding of the second endoscopist plus the agreement reached in the case of different findings. All the participating endoscopists had experience in reading SBCE (i.e., >50 CE per year).

SBCE Selection

A total of 100 SBCEs with various indications, performed from August 2019 to October 2020, were included. All patients were prepared with 2 L of polyethylene glycol and an 8-h fast before the ingestion of the endoscopy capsule. Real-time review was used in all patients. In the event that the capsule did not pass into the duodenum after 60 min, metoclopramide (10 mg i.v.) was administered. If no progress was made after 90 min, the capsule was placed endoscopically in the duodenum. The belt and the data recorder were removed 12 h after they were placed.

Outcome Measures

The SBCE findings were classified by using capsule endoscopy structured terminology (CEST) [9] and divided in 3 groups: (1) positive, if significant lesions such as vascular lesions, ulcers, and tumors were found; (2) equivocal if nonspecific lesions such as erosions or red spots were found; and (3) negative, in the presence of irrelevant lesions or absence of findings. Only positive findings were considered as contributing to a positive DY. As per protocol, false-negative (FN) findings could only present in the first evaluation; they were defined as findings (either positive or equivocal) in the second evaluation not identified in the first evaluation. The recordings were read at a maximum speed of 10 frames per second in a single view, in line with the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Quality Improvement Initiative [10].

Sample Calculation

To calculate the sample size, the formula for the difference of 2 proportions was used. The calculation was based on the results of Min et al. [6] in which the DY of the first SBCE evaluation was 37.5% and the DY of the “back-to-back” SBCE was 62.5%. Epi Info software v3, considering a confidence interval (CI) of 95% and a statistical power of 80%, was used for sample size calculation. The estimated sample size was 70 patients per evaluation; however, to increase power, 100 SBCE recordings were included.

Statistical Analysis

Qualitative variables were calculated as frequencies and percentages. To study the relation between qualitative variables, the χ2 test was used. The interobserver agreement was assessed by using Cohen’s kappa (κ) coefficient. The κ index was divided as slight agreement when the value was <0.20, fair at 0.21-0.40, moderate at 0.41-0.60, substantial at 0.61-0.80, and almost perfect when >0.81. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS v22 (IBM, Chicago IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

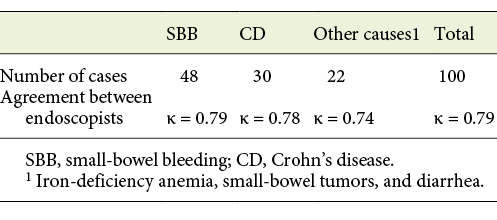

The indications for SBCE were small-bowel bleeding (SBB) in 48 cases, suspected or confirmed CD in 30, and other causes (IDA, small-bowel tumors, and diarrhea) in 22. There was good interobserver agreement between the 2 evaluations (κ = 0.79; Table 1).

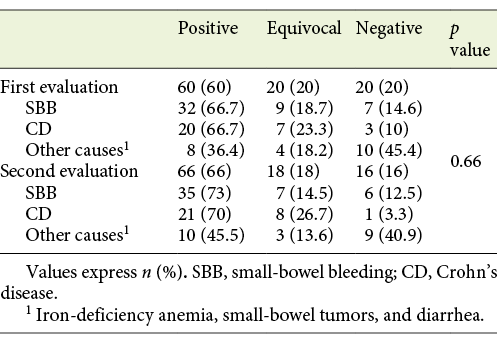

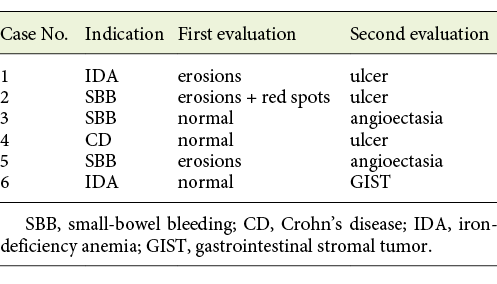

In the first evaluation, findings were considered positive in 60%, equivocal in 20%, and negative in 20% of the cases. In the second evaluation, they were positive in 66%, equivocal in 18%, and negative in 16%. (Table 2). The changes in the type of findings from the second evaluation are detailed in Table 3. On 2 occasions, the intervention of a third endoscopist was required for consensus. These involved a gastrointestinal stromal tumor initially reported as normal and an ulcer diagnosed as “erosions and red spots” in the first evaluation.

The DY was 60% for the first evaluation and 66% after the second evaluation, resulting in a 6% increase (p = 0.38). The increased DY according to the indications was 6.3% for SBB, 4.4% for CD, and 9.2% for others. After the second evaluation, patient management was changed in 4 of these 6 patients; 1 of these 4 underwent surgery, 2 underwent therapeutic enteroscopy, and 1 had their medical therapy changed.

FNs were found in 4% of the SBCEs (cases 3, 4, and 6 in Table 3 and 1 case that went from normal to equivocal) after the second evaluation. The FN rate according to the indication was 2% for SBB, 6.7% for CD, and 4.5% for other indications.

Discussion

The interobserver agreement of SBCE findings has been reported as ranging from moderate to substantial (κ = 0.48-0.71) [11-14]. It also depends on the indications and the experience of the endoscopist. In cases of SBB, it can vary from κ = 0.71 for evaluations by senior endoscopists to κ = 0.56 for those made by junior endoscopists [13]. In CD, the interobserver agreement has been reported as substantial (κ = 0.68) [15]. In our study, the interobserver agreement was substantial and did not vary according to the different indications.

The ESGE Quality Improvement Initiative mentions that currently available data do not support a single optimal DY per indication. For mixed indications, the DY varies between 27 and 77.3% and, for suspected gastrointestinal bleeding, between 31 and 68% [10]. In this study, the DY in the first evaluation was already high at 60%, ranging from 66.7% for SBB and CD to 36.4% for other indications.

There have been several attempts to improve the DY of SBCE. The use of small-bowel preparation, antifoaming agents, or prokinetics has been proposed. Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses to evaluate whether bowel preparation before SBCE improves the DY concluded that there are no clear advantages [16-18]. It has been suggested that a “second-look” with another SBCE can increase the DY. Svarta et al. [19] found positive findings in 55% of repeated SBCEs that resulted in a change in management in 39% of the patients. In our study, a second evaluation of the same capsule increased the DY by 6%; however, it was time-consuming and no statistically significant difference was found.

Van de Bruaene et al. [20] identified FNs in 9% of the SBCEs. They defined FNs as bleeding sources located in the small bowel but not diagnosed during the initial SBCE. In our study, FNs were found in 4%, but our definition of FN was different.

The final diagnosis was changed in 6 cases. Three of these were initially diagnosed as erosions and red spots; in the other 3, the SBCE results were reported as normal. Although not reaching statistical significance, these findings are nonetheless of obvious relevance. In 4% of the patients, a change in management resulted from the reevaluation. In 1 case, a gastrointestinal stromal tumor not diagnosed at the first evaluation and requiring surgical intervention was found. Another 2 patients required therapeutic endoscopy using argon plasma coagulation to treat angioectasia. One patient diagnosed as having CD had a change in medical therapy after ulcers were found at the second evaluation. The diagnosis remained nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-induced enteropathy in 2 patients.

The lack of statistical significance is likely due to the high DY present in the first evaluation. It is at the upper end of previously reported data and similar to the DY obtained after the “back-to-back” approach in the study by Min et al. [6] used to calculate the sample size. This high DY probably reflects improved patient selection and improvements in SBCE technology in recent series. Further studies evaluating gains in DY after interventions, like second evaluations, the use of bowel preparations, or new protocols, should take into account the higher initial DY and marginal increases in DY.

Conclusion

Relevant findings missed in a first evaluation are often identified at a second evaluation, resulting in relevant changes in patient management. Due to the time-consuming nature of SBCE reading, a second evaluation could be selectively offered to negative SBCE patients with suspected pathology. Further studies evaluating interventions to improve the DY of SBCE should take into account the higher initial DY than was previously reported, and, consequently, more modest gains in DY.