Introduction

Alcohol use disorder is one of the most common causes of cirrhosis in the world, affecting around 10% of the general population in both the USA and Europe [1, 2]. Alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) is one of the leading causes of liver transplant (LT), currently representing the second indication for LT in Europe [3]. However, the overall access of patients with ALD to liver transplantation remains low [3].

Alcohol relapse after LT has been reported in 7-95% of individuals, with harmful drinking reported to be between 10 and 26% [4-8]. This broad range is mainly due to the lack of standardized definitions for alcohol consumption post-LT [4-6]. There are known risk factors associated with alcohol relapse after LT, being the most consistently proven younger age, active smoking, poor social support, unemployment, and a family environment with alcohol use [9-16]. Resumed alcohol consumption post-LT has been associated with accelerated cirrhosis development and lower graft and patient survival rates [10, 17-20].

Several scores have been used to access the risk of alcohol resumption after LT, for example, the Alcohol Relapse Risk Assessment, the High-Risk Alcoholism Relapse, and the Sustained Alcohol Use Post-LT scores [20-22]. However, challenges remain in predicting alcohol use following LT based on pre-LT characteristics [23].

The Alcohol Use Disorders Inventory Test (AUDIT) was developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) decades ago, and it has been proven to have good sensitivity and specificity as a screening tool to detect hazardous alcohol drinking in diverse clinical settings across different countries [24, 25]. The AUDIT includes 10 questions that explore alcohol consumption (questions 1-3; also called the AUDIT-Consumption [AUDIT-C]), drinking behavior (questions 4-6), and alcohol-related problems (questions 7-10). Although the AUDIT or AUDIT-C were not designed to specifically assess alcohol use post-LT, they have been used in several studies in the post-LT setting [26-28].

Most reports have only analyzed alcohol consumption in ALD-related LT recipients resulting in limited data regarding alcohol consumption in non-ALD-related patients. A few studies reported similar overall alcohol use rates between ALD-related and non-ALD-related LT patients [29, 30]. Nevertheless, ALD-related LT recipients tended to drink in greater quantities than non-ALD-related ones [29, 30].

Accordingly, we hypothesized that alcohol consumption following LT would be frequent but non-severe in our cohort [1, 4-6]. Therefore, the objectives of our study were the following: (1) to assess the prevalence of alcohol use post-LT based on the AUDIT score in a Portuguese sample of LT recipients and (2) to try to further characterize patients that more likely drank alcohol following LT.

Materials and Methods

Ethics

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee at Central Lisbon University Hospital Center (CHULC), and it was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki [31]. Participation in this study was voluntary, and all patients provided consent before enrollment. The reporting of this study followed the Strobe statement [32].

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional study including all patients who underwent LT between January and December 2019 at Curry Cabral Hospital (CCH), CHULC, Lisbon, Portugal. Patients who had died, were not within reach by telephone or other means of contact, or who declined to participate in the interview were excluded.

Survey Development and Implementation

The survey content was based on the up-to-date literature about alcohol consumption post-LT and comprised questions on demography (date of birth and sex), liver transplantation (etiology and date of index LT, i.e., the first transplant in 2019), actual employment, marital status, actual smoking status, alcohol consumption of housemates, and a validated Portuguese translation of the AUDIT (online suppl. File 1; for all online suppl. material, see https://www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000525808) [33]. All closed-model questions were given specific options for answers.

The survey was reviewed by the authors and underwent pilot testing in the Transplant Unit at CCH to assess comprehension, feasibility, redundancy, and consistency. Necessary changes were made, and surveys were conducted via a telephone call between 8 and 14 June 2021, by 2 senior gastroenterology residents (C.F. and C.C.R.). One patient was an English native speaker and answered the original AUDIT. All the other patients were native Portuguese speakers and answered the translated version of the AUDIT.

Operational Definitions and Endpoints

LT etiology was defined according to the patients’ medical charts. Diagnosis of ALD was based on a history of alcohol consumption, along with compatible clinical, laboratory, or histological findings. At our center, ALD-related LT recipients generally had a minimum of 6 months of alcohol abstinence before LT and a commitment to a lifelong alcohol abstinent behavior. All LT recipients had a favorable psychological or psychiatric evaluation, with screening for any substance abuse disorder. At our center, no LT was performed due to alcoholic hepatitis in 2019 [34].

Employment was defined as working or non-working (the latter including unemployed or retired patients and patients on sick leave). Marital status was defined as married (including cohabiting unmarried couples) or non-married. Alcohol consumption of housemates was defined as yes or no, whether they consumed or not any amount of alcohol, respectively.

The Portuguese AUDIT application targeted only the post-LT period. We defined alcohol consumption (drinking vs. nondrinking recipients) by the patients’ positive AUDIT response to question 1: “How often do you have a drink containing alcohol”? The AUDIT was also used to characterize the pattern of alcohol consumption. The total AUDIT score (0-40) was calculated based on participants’ responses and classified as low risk (<8), low or moderate risk (8-15), moderate or high risk (16-19), or high risk (20-40) [35]. The length of follow-up was calculated from the date of index LT until the date of the survey implementation. The primary endpoint was any alcohol use following index LT.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages, whereas continuous variables as mean and standard deviation (SD), for normal distribution, or median and interquartile range (IQR), for non-normal distribution. No missing data were found, so no imputation was performed.

Continuous variables were compared using Student’s t or Mann-Whitney tests, whereas categorical variables were compared using χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. Multivariable analysis was performed using logistic regression. Variables clinically and statistically significant on univariable comparisons were included in this analysis. Final models were selected based on a backward stepwise approach.

A p value of 0.05 indicated statistical significance (2-tailed). Analyses were performed with SPSS software, version 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

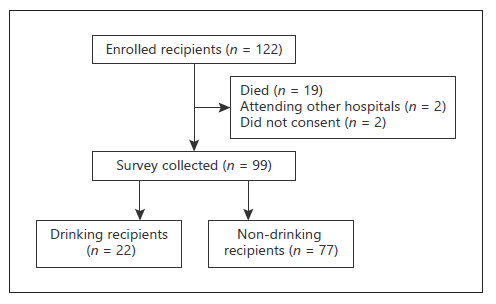

In 2019, 122 patients who received an orthotopic LT at CCH were considered. After the exclusion of recipients who had died (n = 19) or were followed up at an institution abroad (n = 2), a total of 101 patients were asked to participate in the study. Among these 101 patients, only 99 (81.1% of all) patients freely agreed to participate in the telephone interview and were therefore included in the study (shown in Fig. 1).

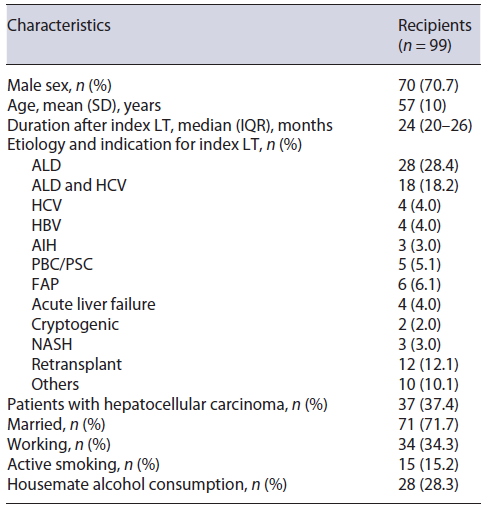

Overall, the mean (SD) age was 57 (10) years, and 70 (70.7%) patients were males. Forty-nine (49.5%) patients underwent ALD-related LT, and 12 (12.1%) index LT procedures were retransplants (3 originally transplanted due to ALD). Median (IQR) follow-up time after index LT was 24 (20-26) months (minimum of 18 months). All baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Characterization of Alcohol Consumption Post-LT

Among all responders (n = 99), alcohol consumption after LT was reported in 22 (22.2%) recipients. Of these, 6 (6.1%) had ALD-related LT and 16 (16.2%) did not have ALD prior to LT. Regarding the patterns of alcohol consumption post-LT, 14 (14.1%) patients had a drink monthly or less and 8 (8.1%) drank 2 to 4 times a month. On a typical drinking day, 18 (18.2%) patients described consuming one or 2 drinks and the remainder no more than 3 or 4 drinks. One (1.0%) patient reported having drunk at least 6 drinks on one occasion. When asked about the type of alcoholic beverage usually consumed, 12 (12.1%) patients reported wine consumption preferably, 9 (9.1%) beer, and one (1.0%) liquor instead. No patients reported alcohol-related injuries whether self or toward others. All post-LT drinking recipients were considered low risk (score <8) as per AUDIT score (median [IQR] of 1 [1-2] and maximum of 4). All drinking recipients with ALD-related LT reported that they drank less after LT.

Risk Factors for Alcohol Consumption Post-LT: Study of Associations

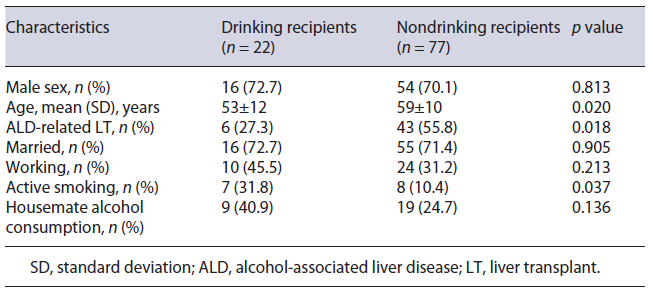

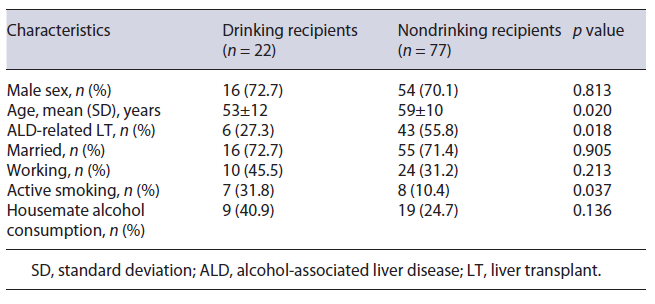

Younger age (53 vs. 59 years, p = 0.020), non-ALD related LT (72.7 vs. 44.2%, p = 0.018), and active smoking (31.8 vs. 10.4%, p = 0.037) were all significantly more prevalent in drinking LT recipients than in abstinent ones (Table 2). Male sex (72.7 vs. 70.1%), married status (72.7 vs. 71.4%), working status (45.5 vs. 31.2%), and living with a housemate who consumed alcohol (40.9 vs. 24.7%) were all more common in drinking LT recipients than in abstinent ones, but those differences did not reach statistical significance. Among drinking LT recipients, the median (IQR) AUDIT score was similar between ALD-related LT and non-ALD-related LT (1 vs. 1, p = 0.914).

To avoid overfitting the models, we included up to 3 variables in the final models of the multivariable analysis (Table 3). Using logistic regression, while ALD-related LT was associated with lower odds of alcohol intake post-LT (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] [95% CI] 0.17 [0.04-0.72]), active smoking was associated with higher odds of alcohol use following transplant (aOR [95% CI] 8.12 [1.72-38.24]).

Discussion

Main Findings and Comparisons with Previous Studies

The main finding of our cross-sectional study was that less than a quarter of LT recipients consumed alcohol following a median of 2 years after transplant. Additionally, all drinkers post-LT had a low-risk pattern as per AUDIT. Finally, alcohol consumption was more prevalent in patients transplanted for non-ALD than those who had ALD prior to LT. In fact, ALD-related LT was independently associated with lower odds of drinking alcohol following transplant.

Up to 2 years after LT, alcohol consumption in our co-hort was within the range described in the literature [11, 23]. However, when considering heavy alcohol consumption, according to the AUDIT-C score, we found a lower relapse rate than previously reported. Actually, we found no heavy alcohol consumption after LT (median AUDIT score of 1). This finding is especially important as it has been established that the higher the quantity of alcohol consumed, the worse the effect on graft function [24, 34]. While our median follow-up time post-LT was higher than in previous studies (24 vs. 19 months), that may not be such a substantial difference, especially because it has been suggested that the longer the time since LT, the higher the alcohol consumption risk [4, 36, 37].

In our study, the most prevalent variables associated with alcohol consumption were younger age, non-ALD-related LT, and active smoking. Alcohol consumption post-LT has been reported to be more common in young-er patients, much like in our cohort [13-16]. Active smoking has also been a well-established risk factor associated with alcohol consumption [11]. According to Ehlers et al. [12], those who resumed smoking after LT were 1.79 times more likely to also drink alcohol.

Interestingly, in our cohort, there was a higher prevalence of alcohol consumption in non-ALD-related LT recipients in comparison to those with previous ALD. There are few studies addressing alcohol consumption in non-ALD-related LT recipients. According to those, there seems to be similar alcohol use between these subgroups or a higher prevalence in the ALD subgroup [30, 38, 39]. A study by Faure et al. [30], wherein 46.7% of patients were transplanted with ALD as a primary indication (comparable to our cohort with ALD-related LT in 49.5%), showed that among the drinking patients after LT, 57.6% of those had non-ALD as the primary indication for transplant but with previous excessive alcohol consumption. In the present study, we did not address previous excessive alcohol consumption, irrespective of LT indication.

In our study, there was no quantification of alcohol consumption before LT. After LT, only qualitative categories from AUDIT were used. Moreover, there seems to be an underestimation of the drinking behavior prior to LT in patients diagnosed with liver diseases other than ALD [40]. Using a screening protocol, Ursic-Bedoya et al. [40] identified, in a timeframe of 6 years, that 72% of the LT candidates experienced excessive alcohol use at some time in their life and only 40% of them were labeled as ALD as the primary indication.

In Portugal, alcohol has been the psychoactive substance with the highest experimental prevalence of consumption, estimated as 86.4% of the general population at any time during life according to a 2017 report [41]. In Portugal, alcohol consumption is generally socially accepted, affordable, and easily accessible, which has led to an onset of alcohol consumption at progressively younger ages [42]. Such wide availability of alcohol remains a challenge in the management of all post-LT patients too.

In our cohort, all drinking recipients with ALD-related LT reported that they drank less after LT. This finding is in line with other studies suggesting that a substantial reduction in alcohol intake following LT may be a relevant endpoint, besides total abstinence. Such reduction in alcohol consumption has been associated with a decrease in overall morbidity, mortality, and health costs, and an improvement in psychosocial status [34].

Some limitations should be considered when interpreting our results. First, drinking behavior was self-reported, and only during the first-year post-LT therefore recall bias may have played a role. Although the questionnaire was conducted telephonically by an unfamiliar physician and confidentiality was ensured, it is known that patients tend to underreport their alcohol consumption [43]. Second, no biochemical screening tools were used to further assess alcohol intake, even if they lack often sensitivity and specificity. Third, the study included only one transplant center, thus caution should be taken when extrapolating these results to other settings. Fourth, at our center, there was no formal surveillance protocol to assess the risk of alcohol intake post-LT, and no addiction experts to help us monitor that risk. Therefore, alcohol in-take could have gone unnoticed and underreported in medical charts.

Despite these limitations, we think that our study adds to the literature as it reports on the prevalence and sever-ity of alcohol use post-LT, based on an easy-to-use and widely accepted validated tool (AUDIT), and using a reasonably large cohort from Portugal. Moreover, it describes possible characteristics that clinicians may need to consider as possible drivers of the risk of alcohol resumption post-LT. Finally, these data raised awareness of the need of taking detailed alcohol use history, irrespective of LT indication, and to adopt a standardized approach to screen alcohol consumption post-LT in all patients, during each visit. This could also include scheduled formal assessments by addiction experts. Future large and multicenter studies, with further tools for alcohol intake surveillance and a longer follow-up period, are needed to improve our knowledge of the alcohol-related behavior of candidates and recipients of LT.