Introduction

Iron deficiency is a common condition among the general population and patients admitted to hospitals [1-4]. Correction of iron deficiency improves quality of life by reducing symptoms of anaemia, increasing sensitivity to erythropoietin stimulating agents, as well as resolution of related conditions [1-4]. Total body iron replacement is common practice in hospital settings for patients intolerant of oral iron supplements, those with malabsorptive conditions, or those with poor medication adherence [3, 4].

Previous research has demonstrated the safety of iron polymaltose (IPM) up to 1,500 mg, administered as a rapid 1-h infusion with the average replacement doses ranging from 1,300 to 1,500 mg [3-5]. However, despite increased medication cost and the 1,000 mg dose per week limit resulting in the need for multiple presentations, ferric carboxymaltose is the preferred iron infusion due to its primary advantage of ultrarapid administration over 15 min [6].

A 2017-2018 pilot study demonstrated expected rates of mild and moderate adverse events (AEs) without serious reactions for the administration of up to 1,500 mg IPM over 15- and 30-min intervals [7]. This sufficiently powered study aimed to validate the results of the pilot, comparing the safety of the ultrarapid IPM infusions to previously published results for 1- and 4-h infusions. Ultrarapid IPM infusions would yield significant benefits for patients requiring total body iron replacement in a single treatment session and reduce nursing time and direct medication costs compared to slower infusions and newer parenteral iron products.

Materials and Methods

This was an open-label, single-centre, phase 4 safety study conducted at a tertiary hospital that provides medical, surgical, women’s health, and intensive care services in Victoria, Australia. Participants were recruited if they were admitted to the study site or presented to the hospital’s infusion centre with a diagnosis of iron deficiency of any cause requiring replacement with intravenous IPM, with calculated doses of up to 1,500 mg inclusive.

Doses were calculated based on patients’ actual body weights and haemoglobin results using the Ganzoni equation from the product information, with adjustments for any blood transfusions. Participants with history of chronic kidney disease (CKD) had their doses capped at 1,000 mg as per local guidelines.

Potential participants were identified via receipt of iron infusion orders by the hospital’s pharmacy department. Consent was obtained from participants’ treating teams and written informed consent from patients. Patients were excluded if their calculated dose exceeded 1,500 mg of iron or if they were unable to provide informed consent. Study participants were administered IPM, diluted in 250 mL of sodium chloride 0.9%, intravenously over 15 min via infusion pumps by nursing staff. Nursing staff were educated on potential AEs and provided with written instructions for monitoring requirements of vital signs. These measures were performed before the infusion, at 5-min intervals during the infusion, followed by 1 h of observations at 15-min intervals, and recorded in the electronic health record system. Infusions were delayed for participants recovering from infections or surgery, until C-reactive protein (CRP) measures were under 100 mg/L and participants were afebrile. Participants who experienced AEs were able to complete the infusions at a slower rate or, if the reactions were severe, had their infusions stopped and restarted only after medical review and if it was considered safe to do so.

The primary outcome was the overall AE rate during the IPM infusions [3, 4, 7]. Secondary outcomes included delayed AE rates during the week post-infusion and the severity of acute and delayed AEs graded as mild, moderate, or severe. Mild acute AEs were defined as those that did not require a change in the infusion rate, treatment, or prolongation of hospital stay; moderate AEs required an interruption or change to the infusion rate, minor treatment such as analgesia, or additional monitoring; and severe AEs included those that required cessation of the infusion without intention to restart and where patients required urgent medical attention with administration of resuscitation or severe allergic reaction medications such as adrenaline, hydrocortisone, or parenteral antihistamine, or prolongation of hospitalization (more than 1 day) [3, 4, 7]. Delayed AEs were graded as mild for those not requiring treatment, moderate where minor treatment was required, and severe for those that required attention of a local doctor or hospital presentation [3, 4, 7]. Additional secondary outcomes were the rates of AEs as compared to historical controls of 1- and 4-h infusions from a retrospective study conducted at the same study site between June 2013 and May 2015 [4] and the participant willingness for repeat ultrarapid infusions of IPM if clinically required. In the retrospective study, the dilutions selected by clinicians included either the 1-h infusions of IPM up to and including 1,500 mg in 250 mL of sodium chloride 0.9% or the 4-h infusions of any calculated dose to be administered in 500 mL of sodium chloride 0.9%, both infused after a 15-min test dose infusion at 40 mL/h [4]. All participants who experienced severe AEs during the infusion were reviewed by an independent medical consultant to adjudicate if the AE was infusion rate related. Data collected by investigators were obtained from patients’ medical records and in-cluded patient demographics, aetiology of iron deficiency, pre-infusion pathology, blood transfusions in the previous fortnight, comorbidities, preadmission medications, and any premedications used. IPM dose, risk factors for adverse effects to iron such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), raised inflammatory markers, and the use of concurrent immunosuppressive therapies were also recorded [3]. Bedside nursing staff recorded AEs on supplied data collection forms which included duration and time to onset, treatments used to manage the AEs, infusion rate adjustments, and whether participants required cessation or reinitiation of infusions after medical assessment. Delayed AEs data were obtained by the study investigators from the participants via telephone 1-week post-infusion or in person where participants remained hospitalized at the study site. Participants were asked about the nature and duration of delayed AEs and whether medical attention was needed. During follow-up, participants were also asked regarding their preference to receive IPM infused at the ultrarapid rate if repeat prescription was indicated.

Statistics

The study was powered to 80%, with two-sided significance set at 5%, requiring 275 patients to detect a change in severe adverse reactions of 3% from an estimated 1% to the previously set cut-off of 4% [3, 4]. This study size also powered the study to detect a total AE change of 5.7%. Allowing for loss to follow-up, 300 patients were planned for enrolment into the study.

Fisher’s exact test was used to compare total AE rates and severities against previously published results for IPM 1- and 4-h infusions [3, 4]. All statistical testing was completed using SPSS Computer Program, Version 25.0. (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Ethics

The study received Drugs and Therapeutics Committee ap-proval and approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee at the study site with reference number AM/50300/PH-2019-189648(v2). The study is registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12619000272190p) and Clinical Trial Notification number CT-2019-CTN-00594-1.

Results

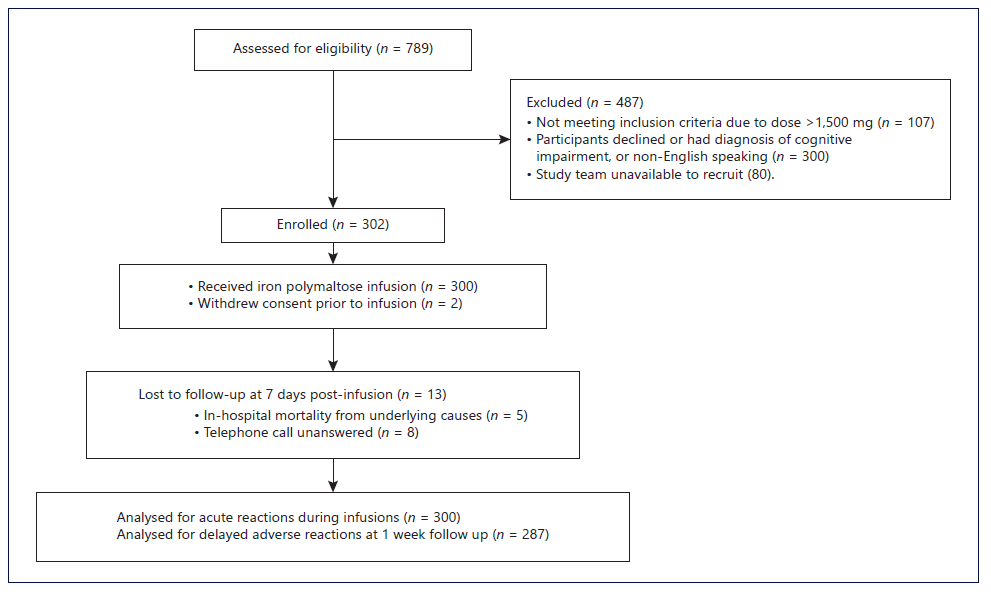

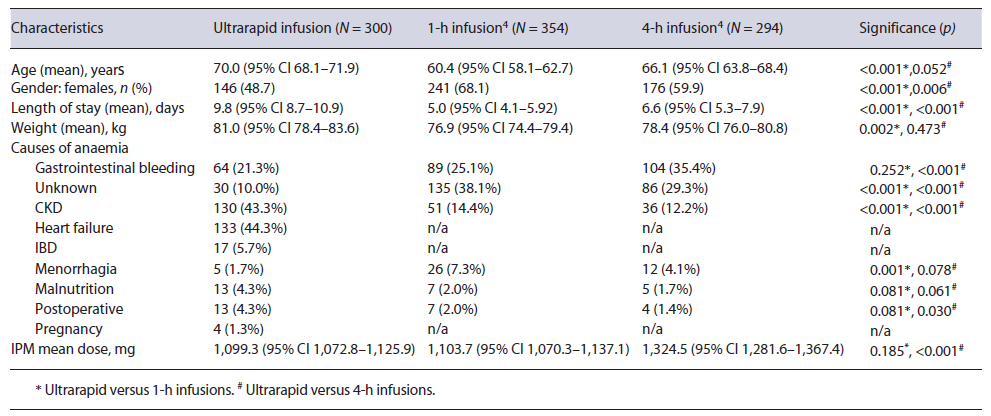

Over the study period (June 2019 to August 2021), 789 IPM infusions were prepared by the pharmacy department, with 487 patients not meeting the inclusion criteria (see Fig. 1). Two participants withdrew from the study prior to the iron infusions being given and were excluded from the final analysis. Three hundred infusions were administered, with 13 participants receiving multiple (two or three) infusions months to years apart. The mean age of the study participants was higher (70.0 years) than that of those included in the 1- and 4-h IPM infusions (60.4 and 66.1 years, p < 0.001 and 0.052, respectively), and there were also fewer female participants (see Table 1). The most common causes of iron deficiency were CKD, congestive cardiac failure (CCF), and gastrointestinal bleeding. Study protocol deviations occurred for 4 participants, where infusions were stopped without resumption at a slower rate after the resolution of mild or moderate AEs. The average dose of IPM administered was 1,099.3 mg (95% CI 1072.8-1,125.9), with 109 (36.3%) infusion doses within the range of 1,100-1,500 mg. These doses were lower compared to 1- and 4-h IPM infusions (p = 0.185, <0.001, respectively). Eighty-nine (29.7%) participants received blood transfusions due to severe anaemia, with an average of 2.7 units (95% CI 2.4-3.0) of blood being transfused within 2.9 days (95% CI 2.4-3.4) before the IPM infusion. Identified risk factors for AEs to iron infusions were: raised inflammatory markers in 149 (49.7%), immunosuppression in 54 (18%), and IBD in 17 (5.7%) participants.

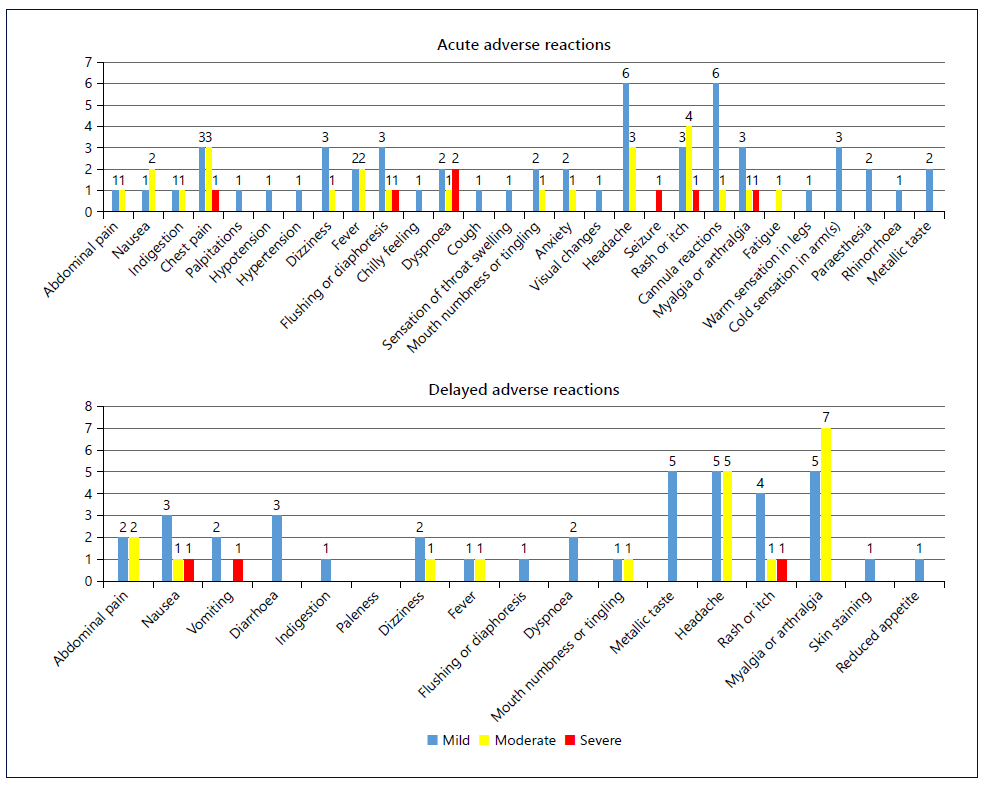

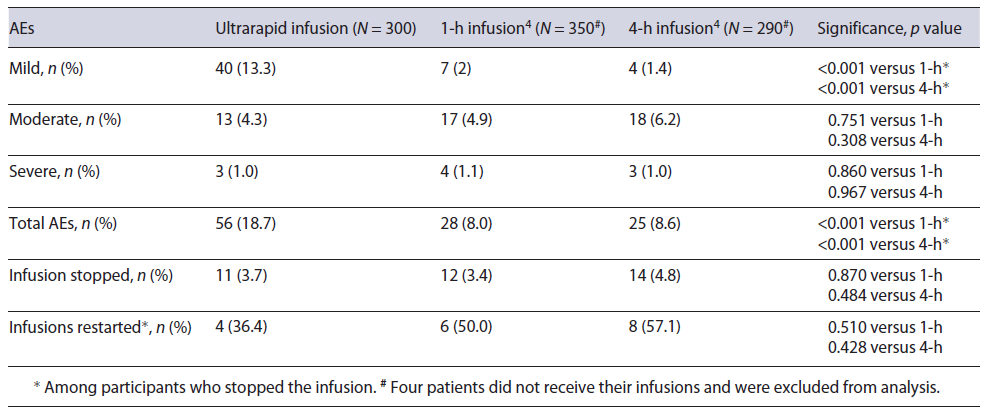

The primary outcome of acute AEs occurred during 18.7% of infusions. The secondary outcome of acute AEs severity comprised of mostly mild reactions (13.3%) with 1.0% graded as severe (see Table 2). The majority of acute AEs did not require treatment, with the most common events being: headaches, cannula site reactions, rashes and itch, as well as chest pain (see Fig. 2). Compared to the slower infusions, the total and mild AE rates were higher (p < 0.001) but similar for moderate and severe reaction rates (see Table 2) [4]. Acute infusion reactions were managed with antihistamines in 2.0%, hydrocortisone in 0.7%, adrenaline in 0.3%, and analgesics in 1.3% of infusions. One participant required antihistamine pre-medication on their second infusion after experiencing a rash during their first infusion a year earlier. There were no AEs during the second infusion. Three participants experienced a severe reaction during the infusion; two were considered allergic reactions with 1 patient experiencing a rash and the other experiencing dyspnoea and a seizure within 15 s of starting the infusion. The third was considered a rate-related reaction with fast onset and resolution of chest pain, back pain, and dyspnoea with infu-sion cessation. No treatment for the reaction or prolongation of hospital stay was required.

Thirteen (4.3%) participants, including three participants who experienced acute infusion AEs (one severe and two moderate), were lost to follow-up (see Fig. 1). The secondary outcome of delayed AEs occurred in 36 (12.5%) participants. Similar to the acute reactions, mild reactions accounted for the majority of delayed AEs (7.3%), with a severe reaction reported in one participant (0.3%). The majority of participants (95.1%) available for follow-up indicated they would accept IPM infusions at ultrarapid rates, if required again.

Participants with a history of IBD had an association for a higher rate of acute AEs compared to those without IBD (29.4% vs. 18.0%, respectively, p = 0.331), but this was not statistically significant. Those with raised inflammatory markers had non-statistically significant lower AE rates (15.4% vs. 21.9%, respectively, p = 0.183). Similarly, associations between AEs and participants on immunosuppressive therapy (including corticosteroids), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin 2 receptor blockers, and who received blood transfusions within a fortnight prior to iron therapy were not identified (see online suppl. Table 1; for all online suppl. material, see https://www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000527794). Participants with CCF or CKD experienced less frequent AEs compared to the rest of the study population (12.0% vs. 24.7%, p = 0.005 for CCF; 12.3% vs. 24.1%, p = 0.011 for CKD). There was no age difference between participants who experienced AEs and those who did not (70.2 vs. 70.0 years, respectively).

Post hoc analysis identified a correlation between iron dose and the rate of acute AEs: 25.7% of participants receiving doses greater than 1,000 mg versus 14.7% of participants receiving between 500 and 1,000 mg (p = 0.021). Severe reactions were also higher where doses were greater than 1,000 mg at 1.8% versus 0.5% among participants receiving between 500 and 1,000 mg (p = 0.299) but not statistically significant.

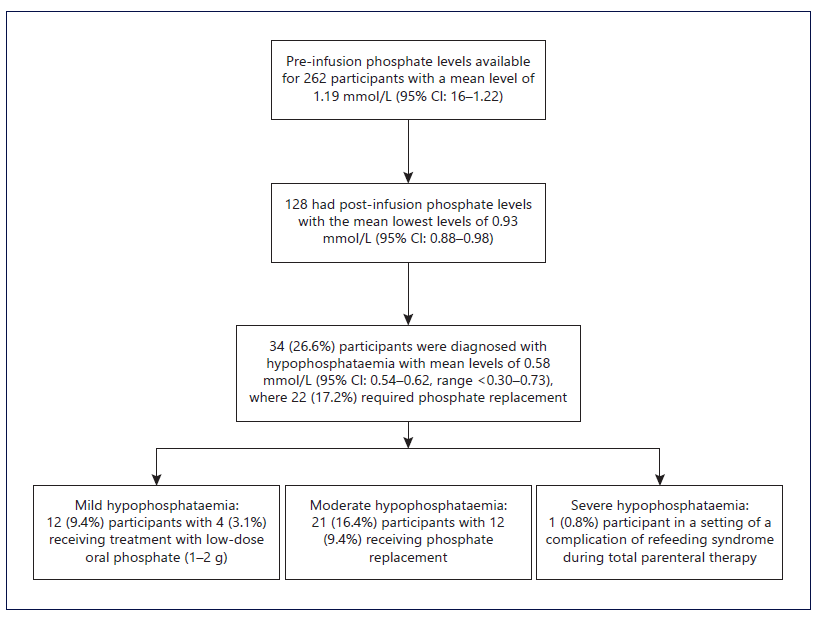

Additionally, in post hoc analysis, another iron infusion-related AE of hypophosphataemia (<0.75 mmol/L) was identified in 34 out of 128 (26.6%) participants with available post-infusion levels (see Fig. 3). The average time to hypophosphataemia post-infusion was 7.8 days (range 1-24 days), with most reaching nadir within 15 days and only three participants experiencing nadir between days 20-24. Normalization of phosphate levels was achieved on average 3.0 days (range 0-8 days) after the nadir, with 22 (17.2%) participants requiring phosphate replacement.

Discussion

The results of this study have demonstrated similar outcomes to the original rapid (1-h) infusion study of IPM, with acute infusion reactions reported at a rate of 18.7% versus 24.0% [3]. However, delayed reaction rates were significantly lower in our cohort with a reported rate of 12.5% versus 26.3% [3]. These differences may be related to a wider spectrum of doses used in the current study, as the rate of acute reactions was 25.7% in patients who received dose above 1,000 mg, which approximates the results from the 1-h infusion study of doses between 1,000 and 1,500 mg [3]. The rates of moderate-to-severe AEs were comparable to both 1-h and 4-h infusions, despite the differences in the population ages, gender, and comorbidity profiles [4].

A similarly designed study of ferric carboxymaltose among patients with iron deficiency anaemia, aged on average 42.4 years, with 87.5% female patients, 12.5% with CKD, 11.3% with IBD, and 21.3% with uterine haemorrhage, provides an effective comparator population [8]. The AE rates were not significantly higher (18.7% vs. 15.0%) and almost identical when comparing doses between 500 and 1,000 mg (14.7% vs. 15.0%) [8]. Importantly, the rate of delayed adverse reactions with ultrarapid IPM was less than half of that reported in ferric carboxymaltose-treated patients (12.5% vs. 29.3%, respectively), including for doses between 1,100 and 1,500 mg [8].

In addition to the similar safety outcomes, this study confirmed that the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin 2 receptor blockers, corticosteroids, and immunosuppressants did not increase the rate of IPM infusion AEs, as was observed in the study of slower infusions [4]. We also confirmed that participants with diagnosed CKD or CCF had significantly lower AE rates compared to the rest of the study participants, a finding that was also observed in the retrospective study of slower infusions [4]. CKD and CCF were frequently diagnosed together among the study participants, and it is unknown if the lower rate is specific to one or both conditions. CKD is associated with reduced immune system function, and this may have contributed to the lower adverse reaction rate [9].

The higher rates of overall acute AEs observed in this study compared to the retrospective study of the slower infusions were considered likely to be due to the prospective methodology. Milder reactions such as paraesthesia, warm, and cold sensations in limbs, metallic taste, and fatigue may not have been documented or even reported in usual practice. These types of AEs contributed to over 20% of all adverse reactions recorded.

The AEs of hypophosphataemia occurred at significantly lower rates using IPM (26.6%) compared to the recent study of ferric carboxymaltose (>70%) [10]. Only 0.8% of participants receiving IPM experienced severe hypophosphataemia compared to 11.3% with ferric carboxymaltose [10]. Most of the hypophosphataemia occurred within the first week after IPM administration and recovered within a few days, whereas with ferric carboxymaltose, the nadir was at 14 days posttreatment and persisted to day 35 [10].

The main study limitations are the single-centre and open-label study design, with a geriatric population, and high prevalence of CCF and CKD. However, given the prevalence of iron deficiency in patients with renal and cardiac failure, this study provides a reliable reference for managing iron deficiency in this cohort. Another limitation included bedside nursing staff recording AEs, with several deviations from the study protocol identified, including recording the adverse reactions by incorrect severity and subsequently not reinitiating infusions, which may have contributed to the results presented. Additionally, post-infusion phosphate levels were checked in less than half of participants during their hospitalization, which would require further study to evaluate the extent and severity of hypophosphataemia with IPM. Notwith-standing the limitation, the included results add to the current knowledge about the AE with this iron product, and given the size and prospective nature of the study, the results support a change in practice.

Based on the similar AE rates for moderate and severe reactions to those of the slower infusions and ferric carboxymaltose, the ultrarapid IPM infusions could be considered a safe alternative. The benefits of this option include reduced nursing time, infusion equipment, and medication cost compared to the use of ferric carboxymaltose for average doses (1,300-1,500 mg), which in Australia is fivefold that of IPM. With ferric carboxymaltose, there is also a direct cost to patients with loss of time to attend second infusions and increased risk of AEs such as extravasation and skin discolouration from additional cannulations [11, 12].

Conclusion

Ultrarapid (15-min) infusions of IPM have been shown to offer a feasible alternative to slower infusions over 1 and 4 h with comparable safety and high patient acceptability. This option would also provide a more convenient and less costly alternative to ferric carboxymaltose infusions, with fewer delayed AEs. Further research on faster administration of larger IPM doses is warranted.