Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) represents the second most common cause of cancer morbidity and mortality in Europe. The screening of average-risk individuals by faecal occult blood testing followed by colonoscopy for positive cases can significantly reduce CRC incidence and mortality. The long-term efficacy in preventing CRC has been associated with the quality of the screening programme, namely, with colonoscopy quality [1].

Colonoscopy quality is greatly dependent on the quality of bowel preparation, affecting all colonoscopy performance measures [2]. The standard recommendation for bowel preparation includes an oral laxative in a split regimen for morning/early afternoon exams or full-dose regimen for late afternoon exams [2].

To improve bowel cleansing, some adjunctive drugs have been tested; however, their role remains controversial. One of these drugs is simethicone, an inexpensive, safe, non-absorbable substance which reduces the surface tension of gas bubbles and thus prevents foam in the colon. Theoretically, simethicone might present several benefits, such as improving the quality of mucosal visualization, the adenoma detection rate (ADR), and the caecal intubation rate (CIR). Furthermore, it also reduces abdominal distension, increasing patient tolerance and comfort, and decreasing the time spent in bubble removal. Previous studies have evaluated the effect of adding simethicone to the bowel preparation laxative on the overall preparation [3-7].

In a meta-analysis of seven randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing bowel preparation with between 80 mg and 300 mg of simethicone or without simethicone, the numberof bubbleswas lowerinpatientswhohadtaken simethicone; nonetheless, no difference in colon cleanliness was found [8]. Recently, two RCTs have reported that supplemental simethicone (1,200 mg) with 2 L of polyethylene glycol (PEG) can improve bowel preparation, bubble score, ADR, and bowel preparation tolerability [3, 6]. A subgroup analysis of a meta-analysis assessing four RCTs found that oral simethicone (400-1,200 mg) increased ADR [5]. The only study assessing the role of simethicone (480 mg) added to a split dose of 4 L of a PEG preparation found no improvement on ADR or bowel preparation. However, it resulted in lower bubble scale scores and a lower intra-procedural use of simethicone [4]. Furthermore, the optimal timing of oral simethicone addition remains undetermined [9, 10]. In summary, previous studies were mostly from Eastern countries, used low-volume PEG-based regimens or non-PEG-based agents, used simethicone in suspension, have shown conflicting results and only one study assessed colonoscopy results in a CRC screening setting.

Our primary aim was to assess the effect on the adequate bowel preparation rate of adding a higher dose of oral simethicone to a split-dose bowel cleansing regimen of 4 L of PEG, compared to a split-dose bowel cleansing regimen of 4 L of PEG without simethicone, in a pure CRC screening setting. Our secondary aims included assessing the impact on bubble rate, intraprocedural use of simethicone, ADR, CIR, and patient tolerability to the bowel preparation regimen in both regimens.

Materials and Methods

Patients

This was a single-centre, randomized, endoscopist-blinded, controlled trial conducted at the Portuguese Oncology Institute of Coimbra, Portugal, from June 2019 to September 2022. The inclusion criterion was patients aged between 50 and 74 years, inclusive, scheduled for colonoscopy after a positive faecal immunochemical test (FIT) promoted by the regional CRC screening programme. Exclusion criteria were similar to those of the CRC screening program: (1) previous diagnosis of CRC; (2) presence of known genetic susceptibility syndromes related with CRC; (3) personal history of inflammatory bowel disease; (4) presence of gastrointestinal complaints (significant changes in gastrointestinal transit in the last 6 months or evidence of gastrointestinal bleeding); (5) a normal colonoscopy in the last 5 years; (6) known or suspected gastrointestinal obstruction or perforation; (7) toxic megacolon; (8) major colonic resection; (9) pregnant or at risk of becoming pregnant or lactating women; (10) known or suspected hypersensitivity to the ingredients of bowel preparation or to simethicone.

All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the study protocol was approved by the Portuguese Oncology Institute of Coimbra Ethics Committee (reference number: 06/2019). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. This study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03816774).

Randomization: Sequence Generation and Allocation Concealment

Patients were randomly (1:1) divided in two groups: 500 mg of simethicone plus 4 L of split-dose PEG versus 4 L of split-dose PEG without simethicone, following a computer-generated list of random numbers, without any restriction or blocking. The computer-generated random allocation sequence was independent of patients. Enrolment was performed by a gastroenterologist not involved in the endoscopic procedure through a scheduled appointment 1-2 weeks before the colonoscopy. Patients were informed about the aims, procedures, benefits, and likely risks associated with their participation in the study and gave written informed consent prior to their enrolment. The allocation of patients was concealed using sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes.

Bowel Preparation Protocol and Colonoscopy Procedure

All patients were instructed to consume a low-fibre diet 3 days prior to the date of the procedure. On the afternoon before the examination day, patients were required to follow a clear-liquid diet only. The intervention group used a PEG split dose plus simethicone: 2 pills of 125 mg of simethicone 15 min before the PEG dose on the previous evening, plus 2 pills of 125 mg simethicone 15 min before the PEG dose ending 3 h before the colonoscopy schedule. The comparison group used the same PEG split dose without simethicone. PEG was chosen because the Portuguese-organized CRC screening offers this laxative free of charge in the primary care centre, and it is the only laxative provided by the screening programme.

Regarding the bowel preparation schedule, patients took 3 L of PEG on the previous evening (or 2 L if the procedure was scheduled after 11:00 a.m.) plus 1 L of PEG (or 2 L if the procedure was scheduled after 11:00 a.m.) in the morning of the procedure, ending 3 h before the colonoscopy. As all procedures were scheduled until 4:00 p.m., there were no evening colonoscopies requiring a same-day full bowel preparation regimen. Before the procedure, the nurses who were not blinded for group inclusion asked patients about compliance and tolerability to the prescribed cleansing regimen and simethicone prescription, if applicable.

Colonoscopies were performed under deep sedation by experienced endoscopists (>1,000 colonoscopies per year) blinded to the study groups. All colonoscopies were performed using high-definition colonoscopes with narrow band imaging (EVIS EXERA III CV185 or CV190, Olympus Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Histological analyses were performed by experienced pathologists (>1,000 gastrointestinal analyses per year) who were also blinded to the study groups.

Outcome Measurements

Patient characteristics included age, gender, occurrence of gastrointestinal symptoms during preparation, compliance to bowel preparation instructions (diet, dose, and time of PEG, dose and time of simethicone pills). Patient self-assessment of the willingness to repeat the scheme was evaluated by a visual analogue scale (1-10; 1 representing the most unfavourable outcome and 10, the most favourable). Colonoscopy data in-cluded the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS) score, a bubble scale as reported by Lazzaroni et al. [11] (registered in the ClinicalTrials.gov site), and the Colon Endoscopic Bubble Scale (CEBuS), intraprocedural use of simethicone (recorded as a categorical variable: yes or no), CIR, withdrawal time, number, size, location, and histological type of polyps or CRC.

The BBPS score standard protocol was followed. Each individual segment score was added to calculate a total composite score. Adequate bowel preparation was defined as total BBPS ≥6 and ≥2 in each segment [12, 13].

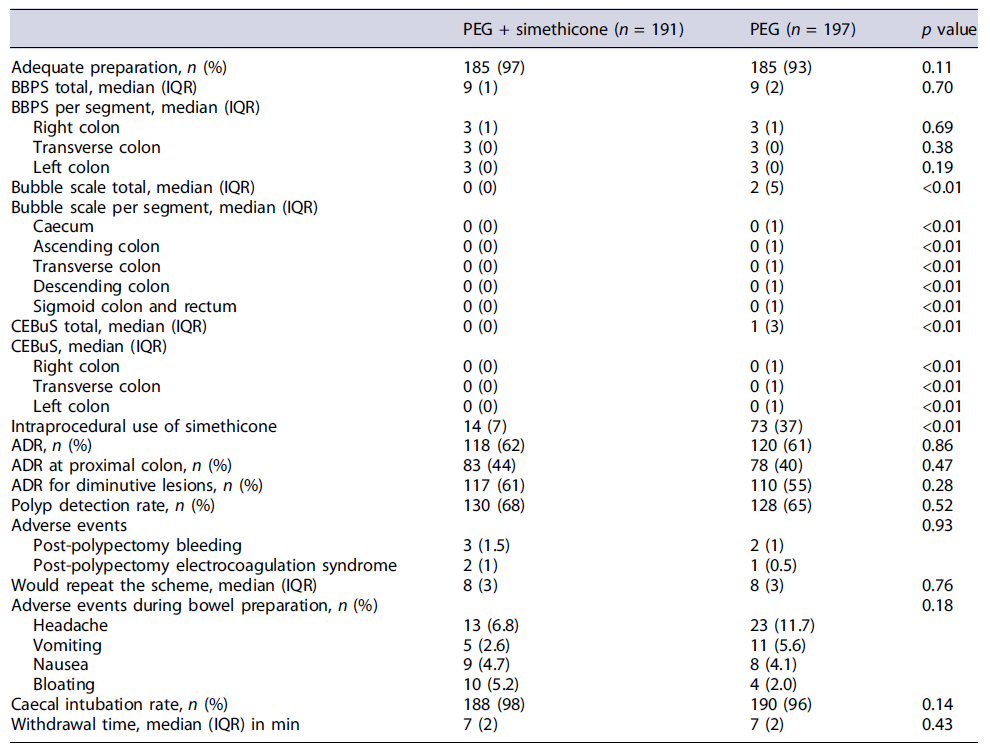

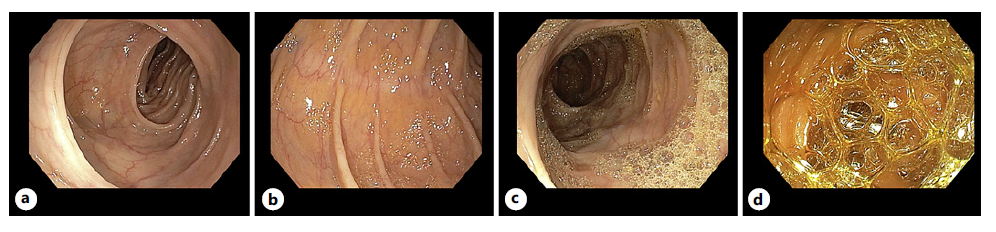

The original bubble scale used in this study was an adaptation from the previously described scale [3, 6, 14]. The score ranged from 0 to 3 (0 [bubbles in <5% of the surface], 1 [bubbles in 5-50% of the surface], 2 [bubbles in >50% of the surface], and 3 [bubbles filling the entire lumen]), as shown in Figure 1, and were determined separately for 5 segments (caecum, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid, and rectum). After the study protocol design, our group published a two-phase evaluation study of a new bubble scale, the Colon Endoscopic Bubble Scale (CEBuS), which was also used in the results [15]. CEBuS is a three-grade scale defined as follows: 0 - no or minimal bubbles, covering <5% of the surface, not hampering mucosa visibility; 1 - moderate number of bubbles, covering between 5 and 50% of the surface, affecting mucosa visibility, and requiring additional time for removal; 2 - severe bubbling, covering >50% of the surface, obscuring mucosa visibility, and requiring additional time for removal (both grade 0 and grade 1 are similar in both scales; CEBuS grade 2 is a combination of grades 2 and 3 of the original scale). In CEBuS, the colon is divided into 3 segments: caecum/ascending colon, transverse colon, and descending/sigmoid colon.

Fig. 1 Bubble scale. a 0: bubbles <5% of the surface. b 1: bubbles 5-50% of the surface. c 2: bubbles in >50% of the surface. d 3: bubbles filling the entire lumen.

ADR was defined as the proportion of patients undergoing colonoscopy in whom at least one histologically confirmed colorectal adenoma was detected. PDR was defined as the proportion of patients undergoing colonoscopy in whom at least one polyp was identified [16]. The withdrawal time was defined as the time spent from the caecum to the anal canal and inspection of the entire bowel mucosa at negative (no biopsy or therapy) colonoscopy and was calculated by time stamp on caecum and rectum photodocumentation [13].

Sample Size Calculation

To improve adequate bowel preparation rate (primary outcome) from 85% (value from our database) to 95% (target standard suggested by ESGE [13]), assuming a normal distribution and a power of 90% (α = 0.05), the calculated sample size of each of the 2 groups was 188. Allowing for a 10% dropout rate, the final sample size was 206 per group (412 patients overall).

Statistical Analysis

Normally distributed continuous variables were reported as mean and standard deviation, and skewed continuous variables were reported as median and interquartile range. Categorical data were expressed as absolute and relative frequency. Continuous variables with a normal distribution were compared between both groups using the Student’s T test, whereas the homogeneity of variance or Mann-Whitney U was used otherwise. Categorical variables were compared using the Pearson’s χ2 test or the Fisher test. A two-sided p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 27.0, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.).

Results

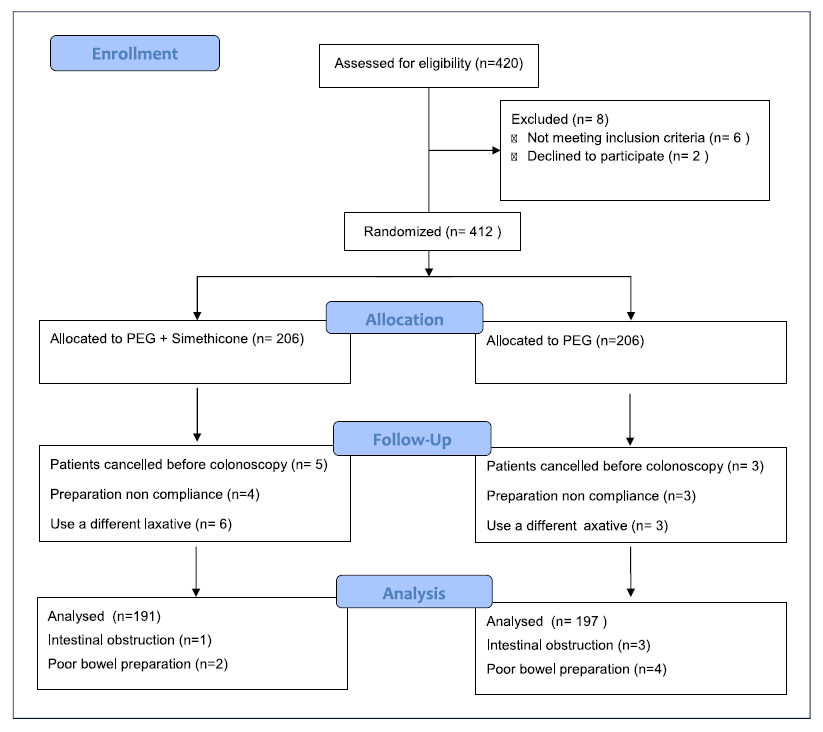

From June 2019 to September 2022, a total of 412 patients were enrolled in the study. Twenty-four patients were not included in the final analysis; therefore, 388 patients (191 PEG plus simethicone vs. 197 PEG alone) were analysed in the intention-to-treat (ITT) and 378 patients (188 PEG plus simethicone vs. 190 PEG alone) in the per-protocol (PP) analysis. The process of patient screening, inclusion, and exclusion is illustrated in Figure 2. The baseline clinical and demographic characteristics were comparable between both groups (Table 1).

Fig. 2 Flow chart of patient recruitment and randomization. PP, per protocol; ITT, intention to treat.

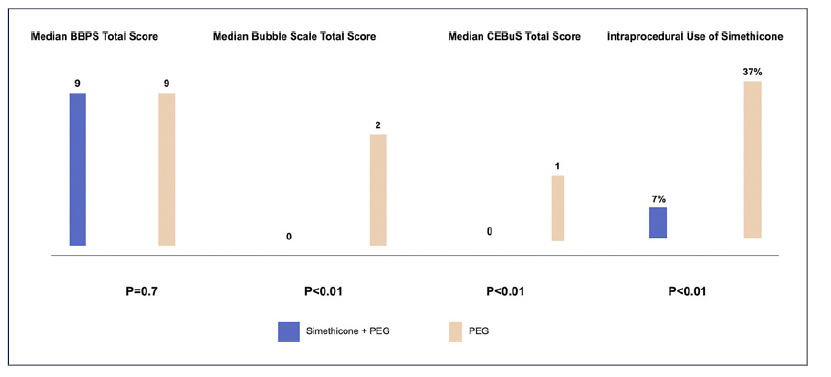

As for the primary endpoint BBPS bowel preparation, the adequate bowel preparation rate was not different between the PEG plus simethicone group versus the PEG alone group, with 97% versus 93% (p = 0.11). The median BBPS total score did not differ between the PEG plus simethicone group versus the PEG alone group (9 [1] versus 9[2], p = 0.70) for ITT and PP analysis. Also, no statistically significant differences were found between groups regarding segmental BBPS scores, both for ITT and PP analyses (Table 2; online suppl. material 1, see online suppl. material at https://doi.org/10.1159/000530866; Fig. 3).

Regarding bubble scale scores, there was a statistically significant difference between groups for the original scale of our study protocol, with patients in the PEG plus simethicone group presenting a better median total bubble scale score (0 [0] versus 2 [5] [p < 0.01]) under ITT and PP analysis. Segmental bubble scores were also significantly better in the PEG plus simethicone group, as shown in table 2 and online supplementary material 1. For CEBuS, patients in the PEG plus simethicone group presented a better CEBuS total score (0 [0] vs. 1 [3], p < 0.01) for ITT analysis and for PP analyses. These significantly better CEBuS score results for patients in the PEG plus simethicone group were also present in the right, transverse, and left colon. Regarding the intraprocedural use of simethicone, the need of simethicone was significantly lower in patients of the PEG plus simethicone group, with 7% versus 37% (p < 0.01) for ITT analysis and 7% versus 38% (p < 0.01) for PP analysis (Fig. 3).

For the ITT analysis, no significant difference was found between the PEG plus simethicone and PEG alone groups regarding PDR (68% vs. 65%, p = 0.52) and ADR (62% vs. 61%, p = 0.86). Furthermore, the ADR in the right colon (44% vs. 40%, p = 0.47) and the ADR for diminutive polyps (61% vs. 55%, p = 0.28) were similar between the PEG plus simethicone and the PEG alone groups, respectively. The results were similar for the PP analysis. The median number of detected polyps (1 [3] vs. 1 [3], p = 0.63) and adenomas (1 [2] vs. 1 [3], p = 0.97) did not differ between PEG plus simethicone and PEG alone groups, respectively (online suppl. material 2). Withdrawal time did not differ between groups: PEG plus simethicone group (7 [2] min) and PEG group (7 [2] min), p = 0.43. Finally, there was no significant difference in colonoscopy adverse events (2.5% vs. 1.5%, p = 0.93) between the groups.

Regarding patient tolerance to the bowel cleansing regimen, no difference was found between the PEG plus simethicone group and the PEG alone group (p = 0.18). Moreover, the willingness to repeat the bowel cleansing regimen did not differ between the PEG plus simethicone group and the PEG group (8 [3] vs. 8 [3], p = 0.76), respectively.

Discussion

The main result of our study was that adding sime-thicone to a split-dose PEG regimen for bowel preparation significantly improved the visualization of the mucosa by presenting better bubbles scores and demanding less simethicone to flush the colon during the procedure, without compromising tolerance or side effects. However, it did not improve the quality of the bowel preparation as assessed by the BBPS, and the ADR did not differ between groups.

We found a significant difference in the mucosa visualization according to both bubble scale scores included in the study [15]. Previous studies have proven a significant reduction in bubble scale score when adding simethicone to bowel preparation, including with doses below 400 mg. However, the scales were subjective and had not been validated. This was the first study to use a validated bubble scale to prove the reduction of bubbles by adding simethicone to a PEG regimen [3, 4, 6, 17]. Another important finding of our study was the significant reduction of intraprocedural use of simethicone in the PEG plus simethicone group. This is of critical importance because recent studies have linked the intraprocedural use of simethicone to the transmission of multiple drug-resistant bacterial infections [18-20]. Although the available data have proven that there is association, although not causality, manufacturers, and the ESGE recommend that when simethicone is needed, it should be injected via the biopsy rather than the auxiliary water channel of the endoscope and at the lowest effective concentration [2, 7]. Our results showed a considerable reduction from 37% to 7% in the use of using simethicone by the channel during the colonoscopies.

Regarding the lack of improvement of the BBPS score, our result was in line with the results by Moraveji et al.[4] but differs from 3 Asian studies that found that simethicone significantly improved the BBPS [3, 6, 17]. However, some differences between our study and these 3 studies should be noted. These studies evaluated the effect of adding simethicone to low volume PEG solution without a split-dose regimen, the dose of simethicone was higher (1,200 mg), and colonoscopies were not performed in a screening setting. Moreover, the higher-than-expected proportion of adequate bowel preparation in our study should also be highlighted. The sample size was calculated for a 10% difference from 85% to 95%, whereas our control group showed 93%, hindering the study power.

Our data also show that adding simethicone to a PEG preparation did not result in an increase in ADR. Our outcome is in line with one RCT from the USA [4]. However, this result differs from another RCT from Asia specifically designed to establish a difference in the ADR. This study, which randomized patients to a 2-L PEG preparation, alone or in combination with simethicone, found a 7% increase in the ADR in the PEG plus simethicone group [3]. In another RCT from Asia, the ADR was 6% higher in the PEG plus simethicone group when a similar 2-L PEG preparation was used, although the study was not designed to establish a difference in ADR as a primary outcome [6]. The discrepancy between our results and the ones from Asia may be explained by the low-volume colon preparation agents used in those studies. Based on the available literature, it is reasonable to assume that the higher ADRs in their PEG plus simethicone groups on a 2-L PEG preparation seem to disappear once a 4-L preparation is used [4].

Regarding the tolerability and compliance, we did not find differences between groups. Our result is in line with most previous studies [4, 9].

Some limitations of our study are worth noting. Firstly, the simethicone dose (500 mg) was higher than the dose used in most studies included in the meta-analysis performed by Wu et al. [8] (<400 mg), which did not show a benefit of oral simethicone in bowel cleanliness and ADR. However, the simethicone dose is lower than two RCTs (1,200 mg) that demonstrated the effect of simethicone in bowel cleanliness and ADR [3, 6]. Secondly, the optimal timing of simethicone addition to PEG remains undetermined. In our study, simethicone pills were administered in a split-dose fashion as the laxative. Previous studies have used simethicone suspension and patients have been instructed to add it to the PEG container before drinking it [3, 4, 6]. Recently, one RCT including only morning colonoscopies demonstrated that simethicone addition to PEG in the evening of the day prior to colonoscopy can shorten caecal intubation time and improve bowel preparation and diminutive ADR in the right colon, compared with simethicone addition to PEG in bowel preparation in the morning of colonoscopy [9]. Thirdly, we reported a higher-than-expected proportion of adequate bowel preparations that could decrease the power of our study.

In summary, adding 500 mg of oral simethicone to a split-dose high volume PEG in a colonoscopy screening setting reduces the amount of bubbles in the colon, as evaluated by a validated bubble scale, and the intra-procedural use of simethicone but does not improve either the BBPS bowel preparation score or the ADR. Further studies are needed to define the effect of a higher dose of oral simethicone in a different schedule.