Introduction

Tuberculosis is an infectious disease caused by the bacillus Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and until the COVID-19 pandemic, it was the leading cause of death from a single infectious agent [1]. About 25% of the world’s population is infected with M. tuberculosis; however, only a small proportion will develop disease during their lifetime, with immunocompromised individuals being the most susceptible group. Although pulmonary tuberculosis is the most frequent manifestation, the involvement of other organs (extrapulmonary tuberculosis) is not negligible, and recent data show that, in some countries, extrapulmonary tuberculosis constitutes up to 30%of all active tuberculosis [2].

Gastrointestinal (GI) tuberculosis is an unusual form of extrapulmonary tuberculosis, although its prevalence may be underestimated due to its nonspecific clinical presentation. The ileocecal region is the most frequently affected site, followed by the colon and small intestine, while the stomach and esophagus are rarely involved [3]. We present a rare case of primary gastric tuberculosis with nonspecific clinical presentation and unsuspected endoscopic appearance, which made this diagnosis challenging.

Case Report

We present a case of a 46-year-old Portuguese woman, who was referred to the Gastroenterology Outpatient Clinic due to epigastric pain, early satiety at meals, and loss of >25% patient’s total weight for 3 months. Her past medical and family histories were irrelevant. The patient denied any other symptoms, and physical examination showed no changes. Laboratory tests (including blood count, coagulation, electrolytes, renal function, liver tests, and C-reactive protein) were normal. An upper GI endoscopy revealed diffusely hyperemic gastric mucosa, which was biopsied (antrum and gastric body). The patient was treated with pantoprazole 40 mg bid and domperidone 10 mg tid but without effect. Gastric biopsies revealed chronic gastritis with some atrophy and marked inflammatory activity with rare non-necrotizing epithelioid granulomas. No acid-fast bacilli (AFB) (Ziehl-Neelsen staining) were observed, and immunohistochemical for Helicobacter pylori was negative.

For investigation of granulomatous gastritis, a careful clinical history (without epidemiological context for tuberculosis) and additional laboratory tests were carried out: interferon gamma release assay negative; angiotensin-converting enzyme 45 U/L (reference range, 8-52 U/L); anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies negatives, fecal calprotectin 502 mg/kg (reference value: <50 mg/kg), and negative stool culture and ova and parasite analysis; HIV and VDRL negatives; erythrocyte sedimentation rate 10 mm/h (reference range: 0-20 mm/h); β2-microglobulin 1.3 mg/L (reference value: <2 mg/L); and normal peripheral blood smear. Chest and abdominopelvic CT scan did not reveal pulmonary nodules, lymph nodes, or digestive tract thickening. Colonoscopy with terminal ileoscopy and biopsies was performed - with no changes.

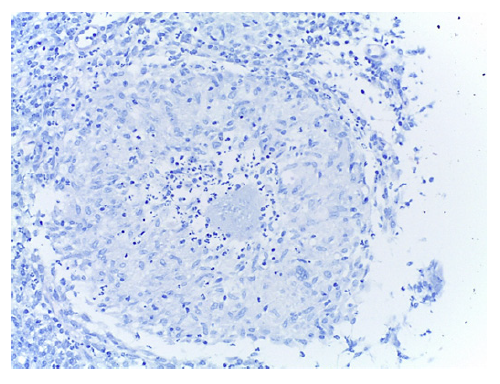

Six months later, after an extensive workup that was inconclusive, an upper GI endoscopy with biopsies was repeated. Once again, endoscopic findings were nonspecific, and the biopsies showed non-necrotizing epithelioid granulomas. Culture (Löwenstein-Jensen medium), immunohistochemistry (MPT64), and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (GeneFinder TB) for M. tuberculosis were negatives. H. pylori was detected and treated with bismuth subcitrate potassium 140 mg qid, metronidazole 125 mg qid, and tetracycline 125 mg qid for 10 days.

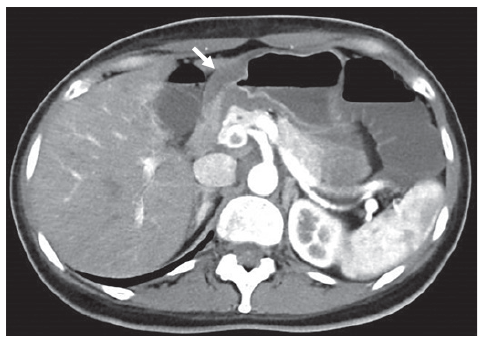

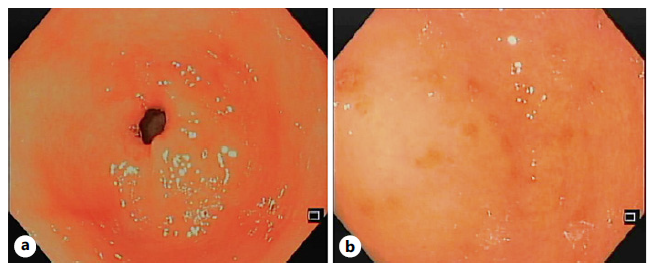

The patient had worsening epigastric abdominal pain and persistent vomiting, unable to tolerate an adequate oral intake, so she was admitted to the Gastroenterology Department. At that time, an abdominopelvic CT was repeated revealing slight (13 mm) concentric parietal thickening of the gastric antrum (shown in Fig. 1). An upper GI endoscopy showed some gastric erosions (shown in Fig. 2), and biopsies were taken from body and antrum of the stomach. Bite-on-bite biopsies were performed in the antrum, and gastric juice was also collected for microbiological study.

Given the suspect of tuberculosis, a bronchoscopy was performed. Bronchial secretions and bronchoalveolar lavage were negative for M. tuberculosis in AFB staining (Ziehl-Neelsen), culture (Löwenstein-Jensen medium and BACTEC MGIT 960), and PCR (GeneXpert MTB/RIF). Capsule endoscopy excluded lesions in the small intestine.

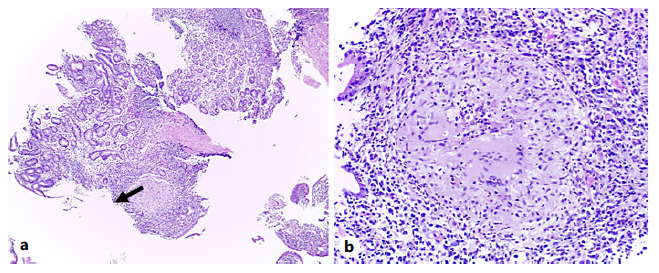

Deep biopsies of the gastric antrum would reveal numerous epithelioid granulomas with central necrosis in the lamina propria (shown in Fig. 3, 4). AFB stain (Ziehl-Neelsen) and M. tuberculosis culture (Löwenstein-Jensen medium and BACTEC MGIT 960) were negative in both gastric juice and biopsies. PCR for M. tuberculosis in fresh samples of the antrum were negative, but positive in paraffin-embedded tissue (GeneFinder TB), thus making the diagnosis of gastric tuberculosis.

Fig. 3 a Hematoxylineosin stain (×4). Antrum-type gastric mucosa with moderate to severe chronic gastritis, with moderate activity, mild atrophy, and expansion of the lamina propria by inflammatory infiltrate, reactive lymphoid aggregates, and an epithelioid granuloma (arrow). b Hematoxylineosin stain (×20). Epithelioid granuloma with central necrosis, some neutrophils, and Langhans-type multinucleated giant cells.

The patient was referred to Infectious Diseases and started treatment with isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol for 2 months, followed by 7 months of isoniazid and rifampin. There was a slow but complete clinical response at the end of treatment. Endoscopic reassessment with biopsies 3 months later was unremarkable, and fecal calprotectin was 95 mg/kg.

Discussion

Gastric tuberculosis is a rare entity, accounting for 0.5-3% of GI tuberculosis cases [4]. Several factors have been described that seem to be responsible for the rare gastric involvement, namely, (1) low pH in the gastric lumen, which has a bactericidal role; (2) the absence of lymphatic follicles; (3) the local immunity induced by the integrity of gastric mucosa; and (4) fast gastric emptying [3-5]. Most cases of gastric tuberculosis occur in patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis [6, 7], due to swallowing infected sputum, but it may also be secondary to hematogenous or lymphatic spread and contiguous spread from the adjacent organ. When no other tuberculosis foci are identified after an extensive workup, it is called primary gastric tuberculosis. The latest is a rare form of gastric tuberculosis, sometimes occurring in the context of ingestion of infected milk products and meat [3-5]. Interestingly, our patient did not have an epide-miological context nor a state of immunosuppression that would increase the risk of infection, which makes the case even more particular.

The few reported cases of gastric tuberculosis show that the clinical presentation is nonspecificand variable, from dyspeptic symptoms to acute GI bleeding and gastric perforation [4]. This characteristic along with the low index of suspicion for this entity, especially in non-endemic regions, is responsible for delayed diagnosis. Abdominal pain and vomiting were the main symptoms in this case, and according to a recent systematic review [8], they are present at diagnosis in 43.5%and 64.4% of cases, respectively. Constitutional symptoms associated with tuberculosis such as anorexia, weight loss, night sweats, fever, and fatigue may also be present. More rarely, presentation with an acute condition like upper GI bleeding or perforation has been described [4].

With regard to endoscopic findings, in our case, there were no specific lesions, only small erosions. However, ulcerated or hypertrophic gastric lesions, often causing strictures and mimicking gastric neoplasms, are consistently described in the literature [4, 5, 7, 8]. Lesions are more frequent in the lesser curvature of the gastric antrum, next to the pylorus, due to the presence of lymphoid follicles in this location and the high incidence of gastric ulcers in this topography, which break the integrity of the mucosa [8].

M. tuberculosis isolation proved to be the most challenging step in this case. Published data regarding the diagnostic sensitivity of the different methods in GI tuberculosis are mostly based on cases of intestinal tuberculosis. Interferon gamma release assay has a diagnostic sensitivity of 77-84%, failing to distinguish between latent and active infection. AFB staining, such as Ziehl-Neelsen, has a low diagnostic sensitivity (17-31%). M. tuberculosis culture has a high specificity, but a very variable sensitivity (usually less than 50%), being considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of intestinal tuberculosis. Disadvantages of the culture are the prolonged incubation time (6 weeks) and allowing only qualitative analysis [9, 10]. Histologically, the most typical findings are granulomas and caseous necrosis. Histopathological examination has a sensitivity of around 68%, and these findings are highly influenced by factors such as the number and quality of biopsies [9]. PCR examination has a very high specificity and a sensitivity ranging from 22 to 65%. Currently, there are fully automated real-time PCR methods (e.g., GeneXpert) that have a higher sensitivity (81-95.7%) and allow simultaneous detection of mutations related to the resistance of M. tuberculosis to rifampicin [9]. In summary, if diagnostic suspicion is high, several diagnostic methods should be explored. The PCR test is one of the most sensitive tests and should be used early.

The diagnostic yield of these methods may be com-promised in cases of gastric tuberculosis since the pathological findings may be present only in the sub-mucosa [8, 11]. Bite-on-bite biopsies (bites are taken sequentially at the same location to expose the sub-mucosa), as well as endoscopic ultrasound-guided biopsies, may be particularly useful in allowing the acquisition of histological material from deeper layers [12]. Although the bite-on-bite biopsy technique has a low diagnostic yield (23.3%) compared to endoscopic ultrasound-guided biopsy, it should be considered as an initial approach as it is cheaper, safer, and universally available [13, 14].

From the study carried out, it should be noted the elevation of fecal calprotectin around 10 times the upper limit of normality. Fecal calprotectin, a protein released by neutrophils, is a sensitive marker of in-flammation of the GI tract, being elevated not only in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) but also in infectious diseases. The usefulness of this marker in the differential diagnosis of IBD and tuberculosis is limited since both entities show high values of the biomarker,

although very high values (>1,000 mg/kg) are sugges-tive of IBD. Studies have shown that a decrease in the fecal calprotectin level after antituberculosis therapy is an important indicator of therapeutic response in GI tuberculosis [15-18].

Antituberculosis drugs are the cornerstone of gastric tuberculosis treatment [7, 19]. Regarding the duration of treatment, although many physicians still consider a longer therapy (9-12 months) to be safer in terms of cure and risk of recurrence compared to the standard duration for pulmonary tuberculosis, there are several recent studies showing that 6-month regimens have been shown to have similar efficacy to 9-month regimens in recent studies [2, 3, 12]. Endoscopic and surgical approach should be reserved for more complex situations, such as cases of obstruction of the gastric tract outlet, GI bleeding, or perforation [4, 19].

In conclusion, primary gastric tuberculosis is a rare entity, whose clinical and endoscopic presentation can be very nonspecific. It is essential to have a high index of suspicion for this pathology, particularly in patients with an epidemiological context, to avoid delay in diagnosis and treatment. Bite-on-bite biopsies showed to be a cost-effective method in obtaining material for histological diagnosis.