Introduction

Common variable immunodeficiency disorder (CVID) is a heterogeneous condition characterized by impairment on B-cell differentiation and antibody production. Patients with CVID present a wide range of clinical manifestations, including recurrent bacterial infections, autoimmune disorders, and lymphoproliferative disorders [1, 2]. The prevalence of CVID ranges from 1 per 50,000 to 1 per 25,000 and is the most frequently diagnosed symptomatic primary immunodeficiency in adulthood [3]. According to the diagnostic criteria from the International Consensus Document on CVID, the diagnosis of this disease requires low serum IgG levels, low serum IgA and/or IgM levels, impairment of vaccine response to at least 1 antigen, and exclusion of secondary causes of hypogammaglobulinemia [4].

Gastrointestinal manifestations in CVID are common, caused by infectious agents (such as Giardia lamblia, Campylobacter jejuni, and Salmonella) and also in the setting of a noninfectious gastrointestinal inflammatory disorder characterized by chronic watery diarrhea and small bowel sprue-like histological changes - CVID enteropathy. A small subset of patients exhibit a rare and severe form of this former condition, leading in some cases to a severe state of cachexia [3].

Case Presentation

A 33-year-old refugee Afghan man was admitted to the emergency department due to chronic watery diarrhea (5-7 non-bloody liquid stools per day) and weight loss (loss of 30% of body weight) in the previous 6 months, associated with marked fatigue that limited the performance of his daily activities. The patient denied having abdominal pain, fever, anorexia, arthralgia, or similar symptoms among his cohabitants.

Past medical conditions included a presumptive diagnosis of celiac disease (CD) 10 years before his admission, when he presented a 6-month clinical condition of watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, and bloating, with no other symptoms. The patient underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy, which revealed macroscopic alterations compatible with CD; however, neither biopsies nor other diagnostic exams were performed at the time. He has been on a gluten-free diet ever since.

The patient had not taken any medications (including over-the-counter drugs and supplements) or antibiotics in the previous 3 months. He had moved to Portugal 4 months prior to the admission, as a war refugee, after staying for a short period in a refugee camp. He also denied prior gastrointestinal surgeries and family history of gastrointestinal disorders.

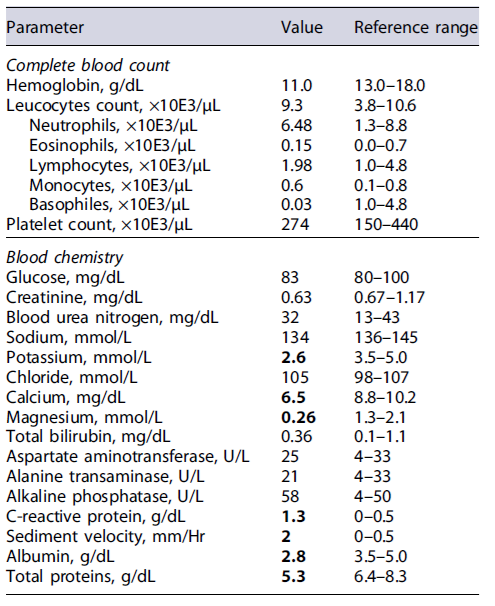

Physical examination revealed a poor nutritional status, with a body mass index of 12.9 kg/m2 (weight 35 kg), and marked skin pallor. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable, and there were no signs of peripheral edema or ascites. At the emergency department, laboratory studies revealed severe electrolyte imbalances (hypomagnesemia and hypokalemia) and hypo-albuminemia (Table 1). An abdominal ultrasound was also performed, and no signs of chronic liver disease, ascites, or bowel wall thickening were present. Due to severe cachexia and electrolyte imbalances, the patient was admitted to the medical ward.

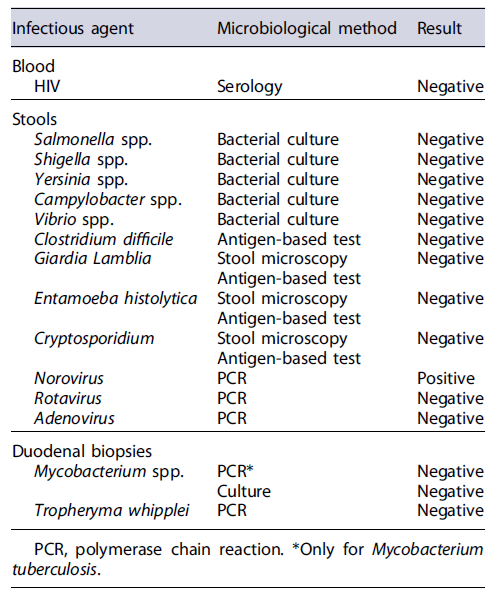

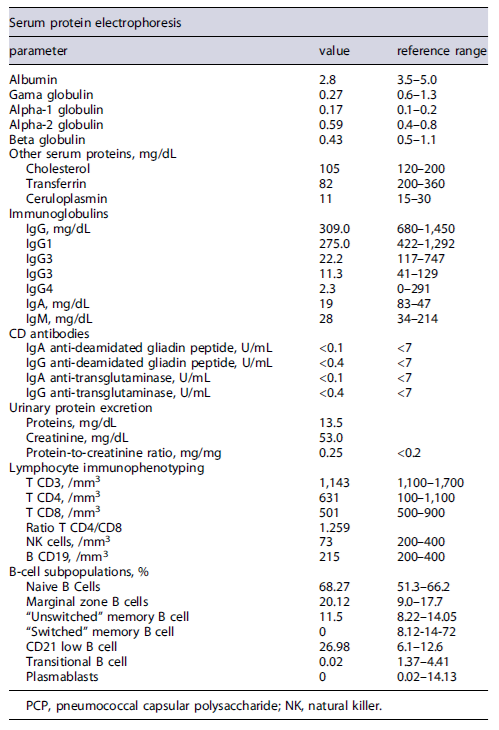

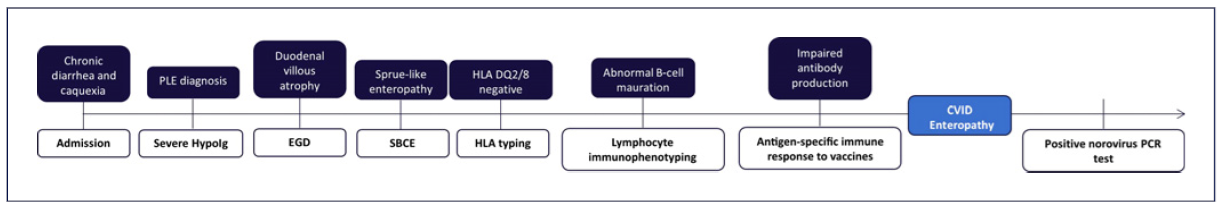

Initial workup included exclusion of infectious gastrointestinal agents (bacterial stool cultures and microscopic stool examination/stool antigen detection for parasites) and HIV serology (Table 2), which were all negative. Extended laboratory data (Table 3) also revealed low serum levels of several proteins, including severe hypogammaglobulinemia, and low urinary protein excretion. Due to the absence of signs of impaired liver function (normal abdominal ultrasound, normal liver enzymes, and no signs of altered mental status) or proteinuria in a patient with chronic diarrhea, the diagnosis of a protein-losing enteropathy (PLE) was made.

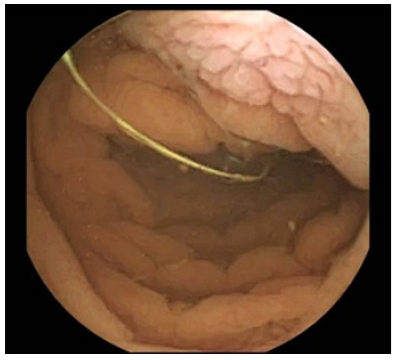

Given the past medical history of CD, the exclusion of refractory CD and intestinal lymphoma was imperative in this case scenario [5]. Despite a negative result of CD antibodies, the patient presented severe hypogammaglobulinemia, so negative serologies could not exclude CD-related complications. Therefore, the patient initially underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy, which demonstrated loss of duodenal folds and a granular appearance of the mucosa (Fig. 1). Duodenal biopsies were collected, revealing distortion of the glandular architecture, with atrophy and flattening of villi associated with an increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL) (>40 IEL/100 cells), and no evidence of granulomas, no thickening of the subepithelial collagen layer, or any signs of dysplasia/malignancy of enterocytes. Small bowel capsule endoscopy was later performed, revealing diffuse duodenal and jejunal villous atrophy, with no ulceration or other lesions (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy, revealing loss of duodenal folds and a granular appearance of the duodenal mucosa. EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy.

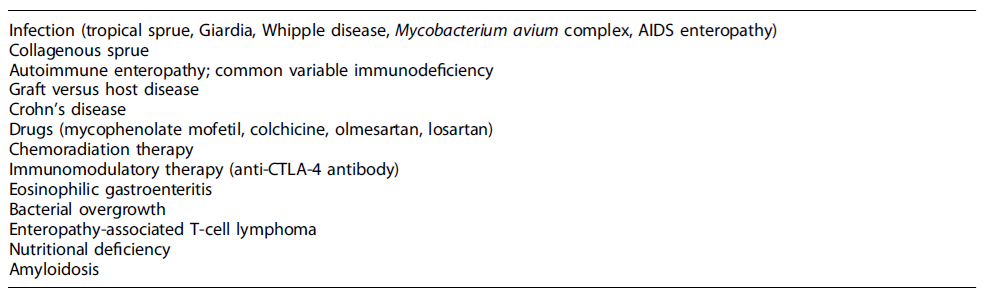

At this point, the physicians were standing before a non-ulcerative PLE, with small bowel villous atrophy and increased IEL, of unknown etiology, with multiple possible differential diagnoses (Table 4). Given his past medical history, refractory CD was initially the most likely diagnosis [5]. Nevertheless, HLA-DQ typing excluded HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 haplotypes, ruling out the initial diagnosis of CD [6].

Concerning other potential differential diagnosis, HIV, bacterial, and parasitic infections were previously excluded. Duodenal biopsies allowed the exclusion of intestinal tuberculosis and Whipple disease. As for intestinal lymphoma, T-cell receptor rearrangement analysis of intestinal lymphocytes did not identify a monoclonal pattern, excluding this condition.

Given that the patient exhibited nonselective hypogammaglobulinemia, an undiagnosed CVID could explain this clinical scenario. Lymphocyte immunophenotyping revealed absence of isotype-switched B memory cells (IgM-/IgD-/CD27), transitional B cells, and plasmablasts. An impairment of B-cell differentiation was evident, establishing the diagnosis of CVID in this clinical setting. This was also corroborated with functional antibody tests, denoting poor immune response to tetanus and pneumococcal immunization.

Later on, due to the fact that patients with CVID and severe hypogammaglobulinemia may develop a PLE related to chronic norovirus infection, PCR testing in stool samples for this agent was carried out, and a positive result was obtained. The final diagnosis of CVID enteropathy with symptomatic norovirus infection of the gut was established.

The patient went through a prolonged hospitalization, with a slow improvement of his gastrointestinal symptoms and body weight. Before the final diagnosis was established, he had initiated oral prednisolone (1 mg/kg/day) and parenteral nutrition. However, due to the scarce clinical improvement and after obtaining the final diagnosis, he was started on intravenous prednisolone (1 mg/kg/day) combined with immunoglobulin replacement therapy (IRT), targeting IgG levels above 1,200 mg/dL (40 g every 4 weeks), and ribavirin treatment (200 mg every 12 h). Concerning nutritional support, the patient initiated parenteral nutrition combined with oligomeric enteral nutrition, followed by a transitory period of polymeric enteral nutrition, and finally a personalized dietary plan with food fortification. After a 3-month hospital stay with an exhaustive investigation, the patient was discharged with clinical and nutritional follow-up in the outpatient clinic, monthly IRT, ribavirin (in order to complete 6 months of antiviral therapy), and weaning of prednisolone.

Discussion

Small bowel villous atrophy is the histopathological hallmark of many chronic enteropathies, which can manifest clinically with a malabsorption syndrome. CD is the most prevalent condition in this context, especially in Western countries. However, differential diagnosis and clinical management of non-celiac enteropathies are still challenging because of their rarity and overlapping clinical and histopathological features [7].

Despite the fact that the patient did not report a personal history of recurrent infections, severe hypogammaglobulinemia on laboratory studies was the first feature that raised the suspicion of CVID [2]. This was corroborated by the demonstration of a poor response to immunization and absence of switched memory B cells, transitional B cells, and plasmablasts [1]. Furthermore, other secondary causes of immunodeficiency were not evident, namely, HIV infection, medications, and hematological malignancies. However, a PLE might, per se, cause immunoglobulin depletion, which made the clinicians seek other possible conditions [8].

The previous misdiagnosis of CD in this patient was a confounding factor and caused a delay in the diagnostic workup, given that a CD-related complication had been primarily assumed [9]. Unfortunately, the lack of standardized endoscopic protocols, availability of diagnostic procedures, and awareness of rare diseases in developing countries had led to the initial misdiagnosis [10, 11].

Even though gastrointestinal manifestations occur in 20-60% of CVID patients, these rarely lead to severe nutritional deficits [12]. In contrast, the authors present a severe case of PLE caused by CVID enteropathy. In fact, a small subset of CVID patients present a malabsorption syndrome, requiring hospitalization and nutritional support [3].

Regarding medical treatment, due to the difficulty of gathering a large number of patients to conduct randomized controlled trials and heterogeneity within the CVID enteropathy, the optimal induction of remission strategy in severe cases is yet to be defined. Medical treatment involves not only IRT but also an immunosuppressive strategy, given that mucosal damage and inflammation are caused by an immunoregulatory dysfunction similar to inflammatory bowel disease [13]. Corticosteroids have shown to induce a positive clinical response in these patients [9, 13], as well as some corticosteroid-sparing agents, namely azathioprine [14], infliximab [15], and vedolizumab [12]. Nevertheless, histological improvement seems to be inconsistent [16].

As described by some authors, these patients exhibit a very slow improvement of clinical manifestations and nutritional status, requiring a prolonged hospitalization [9]. Refractoriness to oral therapy, due to the extensive involvement of the small bowel, demanded a change to the intravenous route. Combined with IRT and antiviral therapy, this immunosuppressive strategy led to a positive clinical response.

Severe intestinal malabsorption in CVID demands the exclusion of norovirus. CVID patients present a cytotoxic aberrant immune response to the chronic infection caused by norovirus, leading to epithelial damage and mucosal villous atrophy [16]. The pathogenicity of norovirus has been further associated with symptomatic and histological improvements observed after viral clearance in several case reports [17, 18]. Unfortunately, for this particular scenario, there are no approved antiviral agents. The decision to start this patient on ribavirin came from the fact that previous authors had reported viral clearance in the norovirus enteropathy associated with CVID after its introduction [3, 19, 20].

Concerning nutritional strategy, after a course of parenteral nutrition, the patient received oligomeric enteral nutrition. Severely ill patients with malabsorption syndromes may benefit from formulas containing peptides and medium-chain triglycerides, as stated by the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) guidelines [21]. Furthermore, polymeric formulas may worsen gastrointestinal symptoms, as opposed to formulas with amino acids [22].

As noted throughout the case description, several other differential diagnoses were considered in this context (Table 4). Infectious causes had to be excluded, namely, Whipple disease, giardiasis, HIV infection, and Mycobacterium species. Additionally, gastrointestinal infections are common in refugee camps due to overcrowding and poor hygiene conditions [23]. Tropical sprue could also fit in this clinical context, given that the patient was from an Asian country, where this condition is highly prevalent [24].

Crohn’s disease and autoimmune enteropathy were also two possible differential diagnoses, requiring further diagnostic procedures (colonoscopy and anti-enterocyte antibodies, respectively). However, given the diagnosis of CVID, these procedures were not performed during the patient’shospital admission [7].

Conclusions

The authors report an exceptional case of a rare non-ulcerative enteropathy in a severely malnourished patient. As previously stated, a PLE with small bowel villous atrophy has a wide range of differential diagnosis, demanding a thorough and exhaustive investigation (Fig. 3). Fortunately, despite the delay in the final diagnosis, the patient had a positive outcome. Clinicians should always keep in mind CVID as an alternative diagnosis in a patient with a PLE. Although IRT is the mainstay of CVID treatment, immunosuppressive therapy is frequently needed to improve mucosal absorption and nutritional status of these patients.