Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), that includes Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), is a chronic, idiopathic inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract. IBD is characterized by an early onset with a relapsing-remitting disease course that requires lifelong treatment. Unpredictable course and challenging complications or symptoms affect the quality of life (QoL) of IBD patients [1], so providing tools to manage the disease and encouraging patients to play an active role in disease management are of utmost importance. A higher level of disease-related knowledge is associated with the development of more adaptive coping among IBD patients [2]. Moreover, knowledge has relevant implications for health outcomes. A higher level of knowledge is associated with reduced healthcare costs [3] and reduced need for step-up strategy in IBD patients [4]. Finally, knowledge measurement tools evaluate educational programs’ effectiveness and identify “gaps” in knowledge [5].

For this purpose, three questionnaires are available. First, in 1993, the Patient Knowledge Questionnaire was developed; however, it is rarely used [6]. Then, Eaden et al. [7], in 1999, published the Crohn’s and Colitis Knowledge (CCKNOW) score; although widely applied, given the emergence of numerous innovative therapies, it currently does not adequately reflect treatment-related knowledge. Recently, Yoon et al. [8] developed a questionnaire, the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Knowledge (IBD-KNOW).

IBD-KNOW is a 24-item questionnaire assessing up-to-date knowledge about IBD, which includes aspects of anatomy, function, diet and lifestyle, epidemiology, general knowledge, medication, complications, surgery, reproduction, and vaccination [8]. The IBD-KNOW was developed and validated in English among patients from various populations.

The main objective of this study was the translation of the IBD-KNOW into Portuguese language and its validation. We also aimed to assess the predictors of a high level of disease-related knowledge and evaluate the association between knowledge and QoL and therapeutic adherence in patients with IBD.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

We conducted an observational, cross-sectional study that included the translation into Portuguese, validation, and application of the IBD-KNOW questionnaire. All participants received a letter explaining the study and gave their written informed consent.

Translation

The English version of IBD-KNOW was translated into Portuguese by two independent bilingual individuals (Portuguese and English). The translations were evaluated, reconciled, and back-translated by two gastroenterologists with English proficiency and experience in following patients with IBD. The back-translators had no prior knowledge of the content of IBD-KNOW. Moreover, a group of five IBD patients filled out the preliminary version to assess comprehensiveness. Finally, the previous gastroenterologists made minor changes to obtain the final translation (online suppl. File 1; for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/ 000530628).

Preparation of the Questionnaire

A multimodal self-administered form was developed, including questions regarding (1) sociodemographic data (age, gender, educational level, employment status), (2) clinical information (IBD subtype, date of IBD diagnosis, family history of IBD, smoking status, previous IBD-related hospitalization and surgery, current medications), and (3) sources of IBD knowledge information. The form also included three questionnaires: the translated IBD-KNOW, the Portuguese version of the Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (SIBDQ) [9], the Portuguese version of the Morisky Adherence Scale 8-item (MMAS-8) [10], and yet the visual analogue scale (VAS) for perceived know For the 24 items of the IBD-KNOW, three choices (“true,” “false,” and “don’t know”) were applicable, with a maximum score of 24 points. We calculated the mean IBD-KNOW score and assessed the factors affecting the level of knowledge. Total higher values of the IBD-KNOW questionnaire represented higher knowledge of the disease.

The SIBDQ was applied to assess health-related quality of life (HRQoL), consisting of 10 questions scored by a 7-point Likert scale. An absolute SIBDQ score of less than 50 was considered a poor QoL. Medication adherence was assessed with the MMAS-8, which includes seven dichotomous (Y/N) and 1 item of the 5-point Likert Scale. A MMAS-8 score equal to 8 meant good adherence. Finally, we applied a VAS for self-awareness about IBD knowledge. It consists of a 10 cm long line, with a mark at the beginning corresponding to very poor knowledge (0) and another at the end corresponding to very high knowledge (10).ledge.

Selection of Patients and Measurement of Patient’s Knowledge

Patients were chosen to participate by convenience, with the invitation addressed to patients who attended the IBD outpatient clinic or the Gastroenterology Day Care Unit at Setúbal Hospital between July and November 2021. Patients who met the following criteria were included: older than 18 years; diagnosis of CD or UC at least 3 months before; at least one previous IBD outpatient visit; and signed informed consent. We excluded patients who completed less than 80% of the IBD-KNOW questions. We asked 15 patients to fill out the IBD-KNOW questionnaire twice with a minimum interval of 1 month.

Validation of Questionnaire

Since there are no external criteria for IBD-related knowledge, validity and discriminatory ability were assessed by (1) applying the IBD-KNOW questionnaire in different groups expected to have different levels of IBD-related knowledge, (2) demonstrating the association between IBD-KNOW scores and surrogate markers of IBD-related knowledge, and (3) assessing the correlation between IBD-KNOW and perceived self-awareness of the disease.

Therefore, the IBD-KNOW questionnaire was submitted to 3 groups of non-IBD volunteers with different levels of IBD knowledge (eleven gastroenterologists, ten nurses, and ten non-medical professional volunteers). For the second hypothesis, the IBD-KNOW score should positively correlate with disease duration. The score should also be higher in patients with higher education; however, it should not differ according to gender and disease type (CD or UC). Furthermore, we analysed convergent validity by assessing the correlation between the IBD-KNOW and the VAS for disease self-perceived knowledge.

Reliability was determined as test-retest reliability (reproducibility) and internal consistency. We assessed reproducibility, asking 15 patients to answer the questionnaire twice, with a minimum interval of 1 month, to decrease the possibility of recalling previous answers (recall bias) [8, 9, 11-13].

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS - Statistical Package for the Social Sciences - version 25.0, with a significance level set at p < 0.05. The normality of variables was verified. Descriptive analysis determined the absolute and relative frequency for categorical variables, the mean ± standard deviation for normal continuous variables, and the median and interquartile range for non-normal ones. Fisher exact tests were used to compare categorical variables. To analyse the association between the score of IBD-KNOW-IBD and sociodemographic and clinical variables, the Mann-Whitney U test, the Kruskal-Wallis H test, Spearman’s correlation, and Student’s t test. Variables significantly associated with high IBD-KNOW score in univariate analysis were included in multiple logistic regression analyses. The internal consistency of the IBD-KNOW was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, which was considered high for alpha values ≥0.70. Reproducibility was assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficient, considered appropriate if ≥0.70. We calculated the sample size calculation for intraclass correlation [11, 13, 14].

Results

Patients

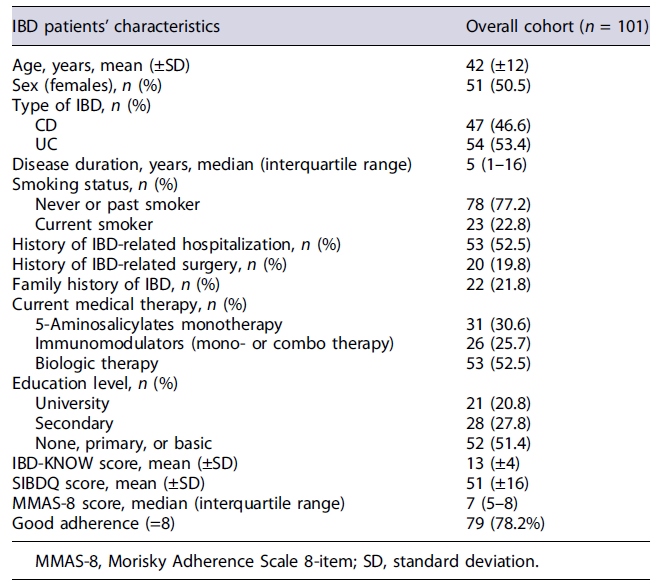

From July to November 2021, 108 patients with IBD completed the multimodal questionnaire; we excluded 7 patients from the final analysis due to less than 80%completion of the IBD-KNOW questionnaire. Thus, we included 101 patients (54 with UC and 47 with CD); the mean age was 42 (±12) years, with a similar number of female (n = 51) and male (n = 50) patients. The mean duration of IBD was 5 years, and most patients were treated with biologics (n = 53). Almost one-fifth of patients (19.8%) had undergone surgery at least once when they completed the questionnaire. Of the patients enrolled, 21 (20.8%) had a university degree. The socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants at the time of completing the questionnaire are shown in Table 1.

Validity

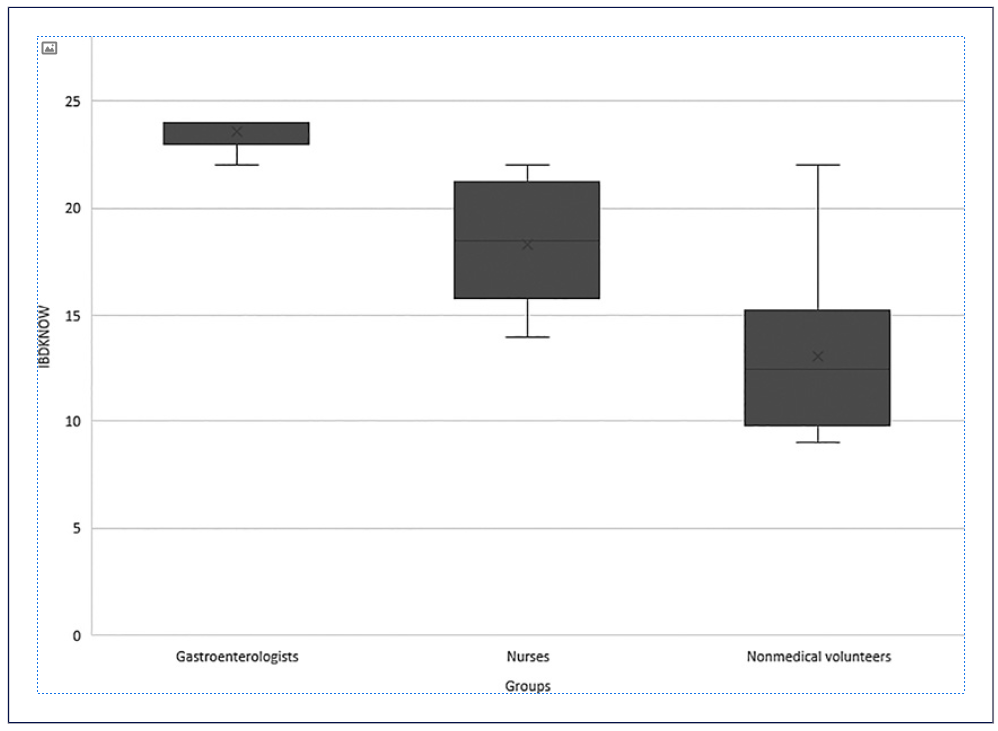

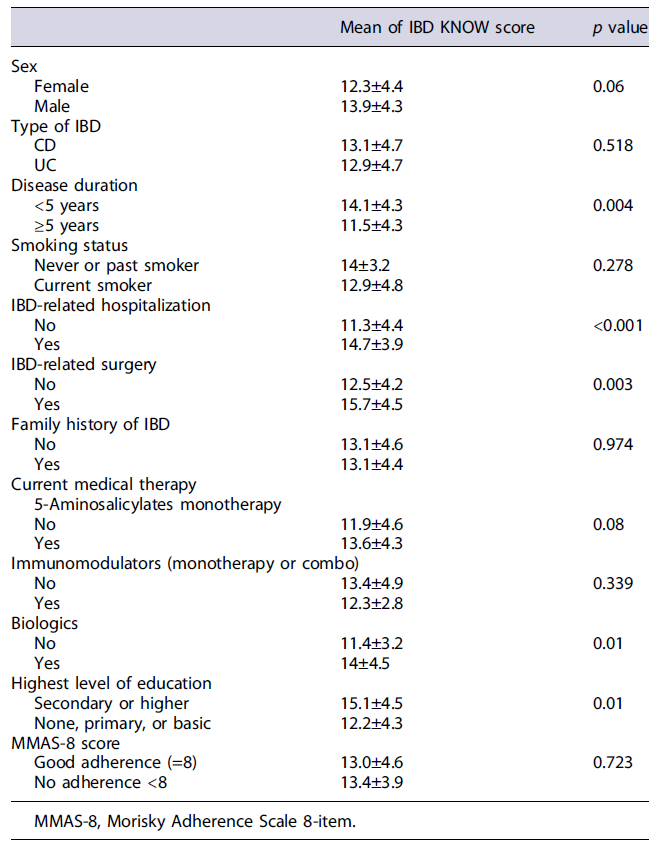

The IBD-KNOW questionnaire was first tested on the three groups of non-IBD volunteers with different expected levels of IBD-related knowledge, including ten non-medical volunteers, ten nurses, and eleven gastroenterologists (seven seniors and four fellows). The mean questionnaire score was significantly different between the three validation groups (12 non-medical, 18 nurses, and 23 gastroenterologists; p < 0.001) (shown in Fig. 1). In addition, the IBD-KNOW score was positively correlated with disease duration (r = 0.606; p < 0.001). The score was also higher in patients with higher level education (secondary or higher vs. primary education or lower: 15.1 ± 4.5 vs. 12.2 ± 4.3; p = 0.01) and did not differ according to gender (female vs. male: 12.3 ± 4.4 vs. 13.9 ± 4.3; p = 0.06) and IBD subtype (CD vs. UC 13.1 ± 4.7 vs. 12.9 ± 4.7; p = 0.518) (shown in Table 2). IBD-KNOW score showed a moderate but significant correlation with VAS for perceived knowledge (r = 0.45, p < 0.001).

Evaluation of IBD-Related Knowledge

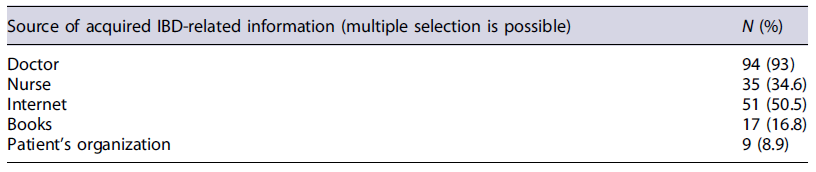

Patients acquired IBD-related knowledge mainly from doctors and the Internet. The sources of information related to IBD are summarized in Table 3.

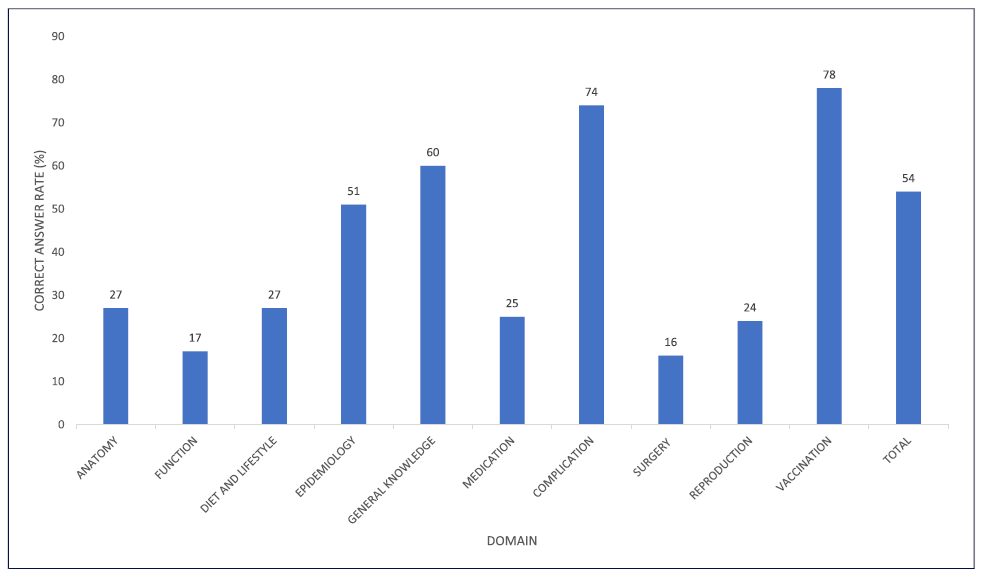

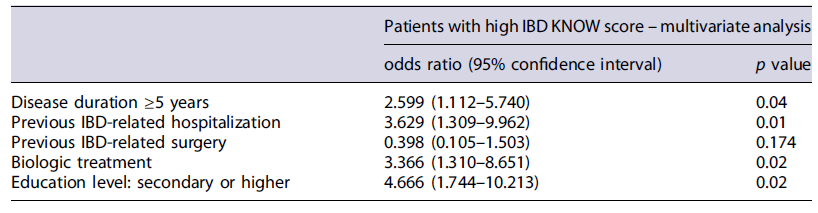

The mean IBD-KNOW questionnaire score was 13/24, with no significant difference regarding age, gender, and IBD subtype. The correct response rate was 54%; the “vaccination” domain performed the highest (78%). The vast majority of patients (74%) recognized the importance of colorectal cancer (CRC) screening in long-term disease. Among the ten domains of the IBD-KNOW, the correct response rate of the domains “reproduction” (24%), “function” (17%), and “surgery” (16%) was the lowest. The correct answer rate for each domain is shown in Figure 2. Univariate and multivariate analyses of the predictive factors for high IBD-KNOW are summarized in Tables 2 and 4, respectively. Multivariate analysis showed that a high IBD-KNOW score (higher than the mean score) was associated with longer disease duration, previous IBD-related hospitalization, current biological treatment, and a higher level of education.

Table 4 Multivariate analyses of predictive factors for high IBD-KNOW score (IBD-KNOW above the mean)

HRQoL in IBD patients (SIBDQ) showed no correlation with IBD-KNOW (r = −0.188, p = 0.383). There was no statistically significant association between adherence to IBD treatment (MMAS-8 = 8) and a mean IBD-KNOW score above the mean (p = 0.552).

IBD-KNOW - Internal Consistency and Reproducibility

We assessed the internal consistency between the 24 questions of IBD-KNOW. We obtained high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α 0.78). Fifteen patients filled out two sets of questionnaires within 1 month. The intraclass correlation was 0.90 (95% confidence interval 0.70-0.96).

Discussion

Patient education is a critical determinant for managing chronic diseases such as IBD. Patient empowerment has been shown to contribute to improved QoL and therapeutic adherence, with consequent improvement in the course of the disease [15, 16]. Therefore, an instrument that objectively measures IBD-related knowledge allows for identifying “gaps” in patients’ disease-related knowledge in order to improve information strategies. This is the first IBD-specifick knowledge questionnaire translated into Portuguese language, which has proven to be a valid and reliable tool to measure IBD-related knowledge in a Portuguese cohort.

There is no gold standard to assess IBD-related knowledge, and there are no previously validated questionnaires in Portuguese. The validity of the IBD-KNOW questionnaire was evaluated, showing that the mean score was significantly different between the groups of non-IBD volunteers, as previously reported in other studies that validated questionnaires assessing IBD-related knowledge [7, 8, 12, 17]. Furthermore, the IBD-KNOW was predicted to correlate with variables which are well-known markers of IBD-related knowledge [6, 7]; these findings were also corroborated by other questionnaire studies [12]. Finally, IBD-KNOW score was significantly correlated with self-perceived knowledge about the disease, similar to previous questionnaire validation studies [18, 19].

The questionnaire also demonstrated excellent test-retest reliability and the Cronbach α of the IBD-KNOW was high (0.78) facilitating comparison between groups of patients. The IBD-KNOW allowed quantification of patients’ level of IBD knowledge and highlighted specific areas where knowledge was lacking. The mean score for IBD-KNOW was 13, similar to the score reported in the original IBD-KNOW publication [8]. The mean score obtained in this study is better than that of Eastern IBD patients but lower than that of North American IBD patients [20]. The mean correct answer rate was similar to the original study [8].

The domains “reproduction,”“medication,”“function,” and “surgery” had the lowest correct response rates, similar to those reported by the original study [8]. Reproduction is a well-known area of knowledge deficit [8, 17, 21]; a more focused questionnaire is available to address this issue [22]. The proportion of patients who recognized the importance of screening colonoscopy for CRC in long-term disease is higher than previously reported in the literature [23]. The question on vaccination showed a very high rate of correct answers, reflecting the knowledge gained from the recent vaccination campaign for COVID-19. Physicians and the Internet were the most important reported sources of information; these results are consistent with previous studies [2, 8, 20, 24].

In addition, we also studied variables with potential impact on the level of knowledge related to IBD. According to previously published studies, a higher educational level was positively correlated with higher scores [8, 12, 17, 20, 21], partly explained by the ease of understanding the more technical terms. Despite the attempt to simplify the response method (“true,”“false,” or “don’t know”)as opposed to traditional multiple-choice tests, in which the influence of education would tend to be greater [17], the level of education remained a determining factor for knowledge levels.

We found that disease duration (≥5 years), previous IBD-related hospitalization, and use of biologics are associated with higher score in multivariate analysis. These findings may be explained by direct exposure to IBD-related environments over an extended period, providing the patient with more opportunities to obtain disease-related information. Danion et al. [17] showed that an IBD diagnosis ≤3 years and the absence of anti-TNFα treatment for IBD are independent risk factors for low levels of knowledge. In addition, other studies corroborated that disease duration [8, 20], previous hospitalization for IBD [8], and use of biologics [20] affected IBD-KNOW scores. The need for step-up treatment strategy or the development of complicated disease (need for hospitalization or surgery) makes patients more concerned about their condition, which drives the search for information related to their illness. Contrary to the available literature [20], our study revealed no difference in IBD-KNOW score in patients with a family history of IBD, which may be due to the significant impact of direct exposure to IBD-related environments (e.g., hospitalization, surgery) among our patients compared to indirect exposure (e.g., family history).

Lack of knowledge about the chronic nature of IBD and fear of adverse drug effects are the most frequently reported causes of non-adherence among IBD patients, particularly those in clinical remission [25]. Few studies have addressed the impact of knowledge on adherence; however, knowledge appears to have a positive effect on compliance [26]. The MMAS-8 is a self-reported survey, and it was the first adherence scale validated in IBD [27], although there are conflicting data on its performance. This scale is more accurate for assessing adherence to oral therapy; previous data showed that only patients on immunomodulators had the MMAS-8 score positively correlated with knowledge [28]. Taking into account that half of our patients were on biologic therapy and these patients generally present with good adherence, it may have contributed to the lack of association between the level of knowledge and adherence in our cohort. Moreover, our patients had a higher adherence rate than that described in the literature [28].

The authors found no association between knowledge and HRQoL in this population. According to previously published studies [2, 29, 30], although education is desirable, knowledge does not necessarily translate into improved HRQoL and well-being. One reason for this finding is that higher knowledge about IBD empowers patients and also creates more anxiety [16].

Our study has several limitations. First, this study was conducted at a single centre, limiting our findings’ generalizability. Second, the relatively small sample size may influence our results. Third, patient association status (e.g., Portuguese Association of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Portugal) was not recorded, which is a well-known factor of better level of knowledge in the field of IBD. Finally, the present study was designed cross-sectionally, so it did not assess patients’ knowledge longitudinally. Therefore, further longitudinal studies and multicentre studies would be needed.

In conclusion, the Portuguese version of the IBD-KNOW is a valid and reliable instrument for measuring patients’ IBD-related knowledge. Further evidence of the validity and reliability of IBD-KNOW will be mostly based on its continued use in the clinical setting.

Considering the growing interest in patient-tailored care model, IBD-KNOW allows the identification of significant knowledge deficits and factors affecting the level of IBD-related knowledge. This is of great interest as it allows rethinking methods of informing patients to increase their health and well-being. IBD teams can develop educational programs that address potential knowledge gaps among IBD patients. Furthermore, IBD-KNOWs allow the objective assessment of the impact of these educational programs. Finally, future studies may explore the role the impact of IBD-KNOW score on patient behaviour (adherence), medical outcomes (medical acceleration), and QoL.