Introduction

Climate change is one of the most, if not the most, important societal challenges of our time 1. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the world has been warming up at an unprecedented rate and is now approximately 1°C warmer than any time before 1850. The global temperature will continue rising until mid-century, independent of future emissions. The impacts of climate change are currently being observed globally. These include more frequent, longer, and more intense heatwaves, drought, heavy precipitation episodes, storms, and wildfires 2. Climate change mitigation - addressing its causes to prevent its worsening - is crucial but cannot provide solutions to ongoing impacts, especially irreversible ones 3. As recognized under the Paris Agreement 3, adaptation to a changing climate is vital. Therefore, many countries, especially in Europe, are deploying adaptation policies 4.

Health risks of climate change include several types of diseases (respiratory, cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, vector-borne diseases, and allergies), injuries, malnutrition, mental health issues (anxiety, depression), and increased mortality 5-7. Many of the health-related harms caused by climate change may be minimized or avoided with timely and efficient adaptation; nevertheless, there is currently an adaptation deficit concerning health 2,8. Moreover, adaptation strategies need to be carefully designed as they may both benefit and harm health 9. As an example, the ill-planed creation of green spaces, widely recognized as an adaptation measure with health co-benefits, may increase issues such as allergens, pests, and insects, while using air conditioning to reduce heat-related mortality and morbidity in urban areas may increase the emissions of greenhouse effect gases and thus aggravate the urban heat island effect 5.

Health vulnerability to climate change is shaped by geographical, social, and economic factors. Risk is not the same everywhere nor for everyone 8. It is important to understand how the negative impacts of climate change translate locally and to implement contextually appropriate and efficient adaptation measures at the local level.

Cities are especially vulnerable as urbanization generates exposures and vulnerabilities that interact with climate phenomena in a way that amplifies risk. For example, the urban heat island may aggravate the impact of heatwaves 7,10, while soil consumption and urbanization may increase vulnerability to flash floods during intense precipitation periods 11. Coastal cities are vulnerable to rising sea levels, floods, and storms 8. Urban vulnerability is growing, thus increasing the risk that climate change poses to urban populations 8,12. Most of the world’s population currently lives in urban areas, and the number of city dwellers is expected to further increase during the following decades 13. This renders urban vulnerability to climate change even more concerning. Socio-economic inequality further aggravates climate change impacts as certain groups, like deprived people, older people, children, and people living with chronic diseases, are more vulnerable to its health impacts 7,8,14. Consequently, adaptation solutions should ensure equity and environmental justice 9.

Considering both the observed and expected negative impacts of climate change on health and the increasing vulnerability of cities and their populations, it matters to develop and implement local adaptation measures that address the health and well-being of city dwellers. Therefore, it is important to understand how cities are including health concerns in their adaptation initiatives and what factors might favour or hinder adaptation, and, specifically, the inclusion of health aspects.

Porto is located in northern Portugal, a European country in the Mediterranean region, which is a hotspot for climate change 15. Portugal is highly vulnerable to climate change 12. Risks include rising sea levels, coastal erosion and overtopping, floods (including urban flash floods), more frequent and intense periods of drought and water scarcity but also of extreme precipitation, higher maximum temperature, more frequent and intense heatwaves, fire hazards, desertification of parts of the territory, negative economic impacts, and social disturbances 12,16-18. Negative impacts on health are also expected, related to heat, air pollution effects, and increased risk of transmission of vector-borne diseases 19. As a result, health services are expected to face increasing demand 17. Given Portugal’s vulnerability to climate change and its level of socio-economic inequality, vulnerable groups are expected to suffer severely. It is thus likely that adaptation to climate change will become one of the most pressing issues of Portuguese environmental policy 20.

Portuguese cities, Porto among them, present several features that render it an interesting case for the study of local adaptation to climate change. These features result from specific vulnerabilities shaped by the city’s geographic position, certain structural characteristics of the Portuguese society, and how both interact and translate locally. Porto is thus a case of intrinsic interest 21 that may enable learning about local adaptation in urban contexts, namely, in Portugal and southern Europe.

This study aims to qualitatively investigate if, and how, public health aspects are included in climate change adaptation planning in Porto (Portugal). Specifically, this study seeks to assess (1) reported climate change risks, with a focus on health risks, and (2) the incorporation of public health aspects in adaptation efforts, as well as obstacles and opportunities to do so.

This article consists of a single case study of Porto, Portugal, about the inclusion of health concerns in local climate change adaptation. However, it resulted from an international multiple case study on the same subject, which has been published elsewhere 22.

Materials and Methods

Case Description

Porto has an area of 41.42 km2 and circa 232,000 inhabitants. It is the centre of the Porto Metropolitan Area (PMA), an urban region composed of 17 municipalities, spreading over 2,040 km2 and with more than 1.7 million inhabitants 23,24. Besides its geographical features (a southern European coastal and riverine city) and climate, it presents several vulnerabilities to climate change health-related risks, such as an ageing population, socio-economic inequality, poor outdoor and indoor thermal comfort, and energy poverty, as discussed below.

The climate of Porto is temperate. Summers are dry and mild, while winters are cool and rainy. Annual precipitation varies between 1,000 and 1,200 mm, and the average yearly temperature is between 13°C and 15°C 25. But it is also demanding for human health due to high levels of seasonal, monthly, and daily variability and seasonality 26,27. Expected local climate change effects include heatwaves, diminution of total accumulated precipitation, increase of extreme precipitation episodes, and sea level rise 25. Warming is already occurring and is expected to increase in the future, with heat waves becoming longer and more intense 27. The city has limited ability to offer comfortable indoor and outdoor temperatures 28. This is all the more concerning as Porto, like Portugal in general, has an ageing population 26. The ageing ratio of the country is 167 older adults per 100 young people, a value that increases to 216.5 in Porto alone 29. Furthermore, part of the population does not resort to artificial systems to keep the houses at a comfortable temperature, often because it lacks the resources to do so 26. This reflects the national reality, as Portugal is one of the European countries where energy poverty is more widespread, with considerable vulnerability to both indoor heat and cold. While the Portuguese climate is mild, residential buildings are often old, inefficient, and of poor quality. Moreover, energy prices are high, the welfare system is inefficient, and the country presents high socio-economic inequality 30,31. The issue of inequality is especially pressing in Porto: using data from Statistics Portugal 23,32, we calculated that the proportion of beneficiaries of the Social Integration Income (an integration programme directed at people in situations of extreme poverty that includes a basic cash benefit in return for abiding by the terms of a contract intended to promote social integration) corresponds to 2.5% of the Portuguese population, a number that rises to 6.5% in Porto alone. Despite its mild climate, and while excess winter mortality is a well-established phenomenon, Portugal suffers from one of the highest rates of excess winter mortality in Europe 33. This is a reality that is not expected to significantly change with climate change. However, excessive heat-related summer mortality, which has also been commonly observed in Portugal during heatwaves 34,35, may increase 30.

In 2015, a new National Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change (ENAAC) recognizing the importance of the local scale of adaptation and later prorogated to 2025 was approved. In the following year, Porto’s Municipal Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change (EMAAC) was, together with the EMAACs of other 25 municipalities, developed under ClimAdaPT.Local, a project that contributed to building adaptation capacity at the municipal level 36. Later, in 2018, PMA published Metroclima, which is relevant for its 17 municipalities.

Procedures

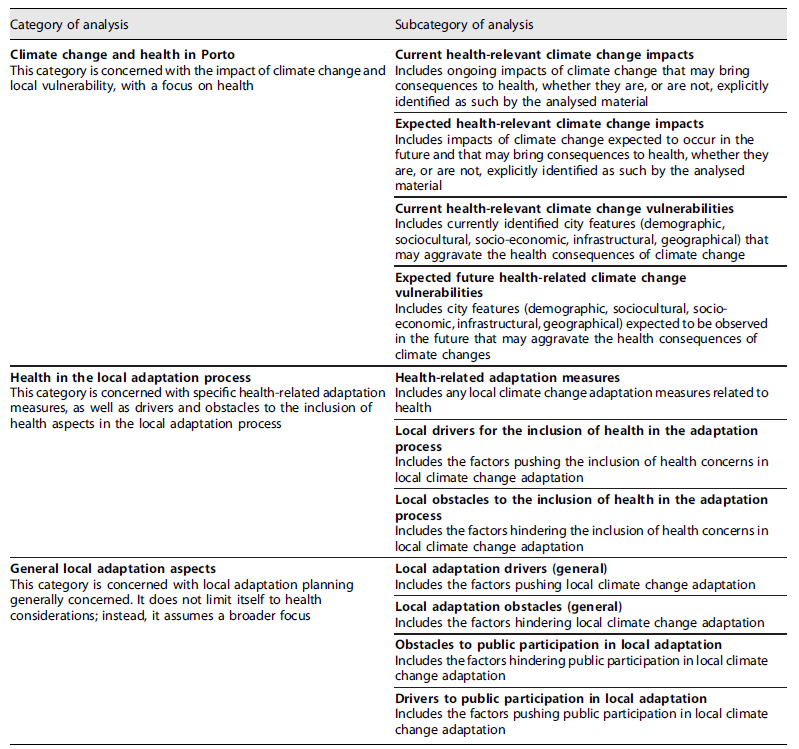

We analysed both the Municipal Climate Change Adaptation Strategy (EMAAC) 25 and the Metropolitan Plan of Adaptation to Climate Change, Metroclima 37, which is relevant because Porto is part of the PMA. These documents were selected for this study because, unlike sectorial plans, they focus on climate change adaptation in a holistic way and are key to all aspects of the local adaptation strategy for Porto and the PMA. We also conducted semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders to deepen our perspectives on the issue. The interview guide is supplied as online supplementary material (online suppl. file 1; for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000540747). Our purposeful sample included six key stakeholders, three men and three women, with ages between 46 and 60 years old at the time of the interviews, all of them selected as information-rich cases 38. We selected local stakeholders with considerable knowledge about local climate change adaptation but also with different professional roles and institutional affiliations, to ensure both richness of information and diversity of perspectives. All interviewees are (or were until recently) connected to institutions headquartered in Porto. The sample included two city planners, two academic researchers, one public health officer, and one politician. The small number of interviewees is justified both by our purpose of gathering information about the local adaptation process from a few information-rich key stakeholders as a way to supplement the analysis of official documents and by the low number of people working locally on the topic of our study. All interviews were conducted over the Zoom platform in March 2021, in Portuguese language, by the same author, and recorded for transcription. The duration of the interviews ranged from 49 min to 1 h and 24 min. For confidentiality and anonymity reasons, we will not match any interview content to professional or institutional roles or demographic data, although doing so could allow the reader to better frame the content. Both the documents and interviews were subjected to a qualitative content analysis 39 using NVivo software (Release 1.0). One author used a previously generated categorization matrix to analyse the materials with flexibility to create new analytical subcategories during the analytical process if needed, always within the bounds of the initial matrix. The result of this procedure was discussed with another author. The final analytical matrix is presented in Table 1.

Results

Climate Change and Health in Porto: Climate Change Impact and Health

The analysis of EMAAC and Metroclima presents Porto as a city where climate change already has an important impact, including on the health of its population. Globally considered, those documents reveal an increase in admissions and mortality in the four main hospitals of the PMA during episodes of both extreme heat and cold; changes regarding precipitation, with increasing episodes of both extreme precipitation and drought; such as high waves; heavy precipitation and storms resulting in structural damage; power supply interruption; dislodgement; and injuries. According to Metroclima, outside Porto, but within the PMA, there are several locations at risk of forest fires, which may negatively affect health in Porto by increasing air pollution 8.

Regarding the expected impacts of climate change in Porto, the most serious risks are related to sea level rise, heavy precipitation and flooding, and higher temperatures and heatwaves. EMAAC identifies many direct and indirect impacts of climate change, several of them potentially costly for health: retreating from the coast; urban flooding; restrictions concerning water consumption and supply; worse water quality; infrastructural damage; fall of trees; landslides; dislodgements; more frequent rescue operations; higher levels of noise due to changes in traffic patterns; higher domestic consumption and expenditure with electricity and water; restrictions concerning open-air activities; and more frequent episodes of ozone excess. Considering this, the “intensification of health damage” and the “clogging of emergency and clinical care channels” are also expected. Disease outbreaks are expected due to emerging diseases (particularly vector borne) arriving from tropical and subtropical climates. According to Metroclima, forest fires (in Porto’s neighbouring municipalities), strong winds, and drought will also occur more frequently and out of season.

Interviewees expressed concern with most of these impacts, namely, sea level rising and coast overtopping, vector-borne diseases, water and air (including indoor air) quality degradation, heavy precipitation and flooding, and extreme temperatures. Regarding the latter, although an increase in temperature is expected in Porto, two interviewees suggested that extreme cold episodes were more concerning than heatwaves:

We will also have an increase in temperature, but also an increase in cold weather episodes. Therefore, we have climatic extremes, but in Porto more people die from cold than from heat.

Climate Change and Health in Porto: Local Vulnerability and Health

Our analysis reveals a concern with the increased vulnerability of older adults, immunosuppressed persons, children, and poorer people, aggravated by the generally poor quality of housing, which presents inadequate energy efficiency and thermal comfort: older adults and the immunosuppressed are more susceptible to temperature variations, while socio-economically deprived individuals lack the resources to keep comfortable indoor temperatures by using artificial systems. According to EMAAC, more than 53,000 Porto residents, all at least 65 years of age, are expected to become vulnerable to indoor heat due to heatwaves. Many of the above vulnerabilities interact and amplify each other as illustrated by the following quotes:

In Porto, there are still signs of deterioration of the built property, especially the oldest one. I am referring to the housing property. That brings some difficulties, in face of extreme temperatures, because the houses are not adequately prepared. Because they are old buildings, they are not adequately prepared and, usually, older people, thereby fragile, live in those old buildings. In this aspect, I think, there is a lot of work to do, while, in other countries, these changes have already been put up for the best. (Interview 1)

Yes, in Porto there is an absolute stratification of climate impacts, regardless of climate change, on different social groups. Because it is evident that the climatic effects for people who have good houses, with good quality construction, and money to pay for the necessary energy to acclimatize, to do what is lacking, are much lower than the impacts for people with low economic resources. From this point of view, Porto is a paradoxical city, that is, a city with profound social inequality. (Interview 5)

Other vulnerabilities presented by our data as a whole include the economic crisis; the high cost of energy; the dissolution of solidarity ties in deprived areas; high water consumption; low number of CO2 sinks; insufficient information about the local climate; fragmentation of green space; soil impermeabilization; the use of inadequate temperature thresholds to issue warnings; the current mobility model; the modern way of life; negligence and low interest for climate change adaptation within the PMA; atmospheric pollution; urbanistic pressure; deficiencies of the water management system; wildfire-prone areas within the PMA; the risk of infrastructure disruption; and the high density and degree of consolidation of the urban infrastructure.

Health in the Local Adaptation Process: Inclusion of Health in Local Climate Change Adaptation

EMAAC presents a range of measures explicitly related to the impact of climate change on health. They include topics such as the capacitation of the population concerning climate change issues; vector-borne diseases; allergies; melanoma; health services capacity; social support networks and vulnerable group support; heat islands; heat and cold waves; accessibilities for rescue vehicles; and on foot and bicycle mobility. Metroclima presents suggestions such as promoting healthy lifestyles, support to vulnerable groups, healthcare access, air quality monitoring, and food supply quality.

Some measures are not explicitly linked to health by these documents but are still related to it. EMAAC includes measures regarding water and river management; protection and management of the coast; land use; civil protection services; meteorological monitoring and forecasting; energy efficiency of buildings; and requalification of cliffs. It also includes the production of specific plans, such as an emergency plan for natural risks, a plan for protecting the coast against sea level rise and coastal overtopping, and a plan for extreme temperature episodes (both heat and cold). In Metroclima, there is a call for action concerning local climate monitoring; land use; coast management and protection; implementation of nature-based solutions that simultaneously contribute to climate change adaptation, improvement of life standards, and the exploitation of technological and scientific advancements; civil protection services preparedness; protection of at-risk structures; and protection of ecosystems.

Many of these measures were discussed during our interviews. Additionally, one interviewee explained how the local government is studying using fiscal incentives to promote beneficial ecosystem services:

So, we are also trying to study these ecosystem services. Because, deep down, we want to account for their value, right? And we even want to work here on a system of regulations and taxes that, in fact, looks at a century-old tree and realizes that it produces a set of ecosystem services for the community… and the owner, just for not cutting it, should already be compensated. Or, at least, he shouldn’t be overcharged. (Interview 3)

The abundance of measures related to different health-relevant impacts of climate change impacts suggests that, as two of our interviewees stated, health is an essential, transversal theme to local climate change adaptation planning:

From the start, when we have concerns such as, for example, the increase in green spaces, not only in the response that they have to give more in terms of the functioning of the ecosystem, to guarantee permeability, or oxygenation, but also very much as a space for interaction between people, designed to respond to an increasingly dependent population, older adults, etc. So, we are cautioning public health concerns. When we are working on a network of proximity equipment that ensures that populations can often overcome the need for access to certain goods and services through walking, we are contributing to health. So it is transversal, so we don’t have, let’s say, a specific chapter only directed to health, many of the options have this big objective. (Interview 6)

Health in the Local Adaptation Process: Drivers of Local Climate Change Adaptation and Health Inclusion

The interview data revealed a set of circumstances creating a favourable context for the implementation of local climate change adaptation in Porto. Some of these are described as being specific to the city, while others are wider in scope but locally relevant. Beginning with the latter, interviewees recurrently talked about climate change awareness in Portugal, which was described as being already significant, but still growing. According to them, this is especially so among the younger:

I think there is a great awareness among the new generations. The older generations, my generation and the others, have also been… because of a very simple thing: because of the extreme events that have been happening in the world. And… and people start to realize, even older adults… for example, my parents are almost eighty years old, they say: “man, there’s something strange going on here.” (Interview 4)

The increasing awareness in Portuguese society is related to a growing global awareness, and also to the importance of media attention to climate change, which EMAAC identified as an enabler of an awareness measure that seeks to introduce climate change topics in local schools. According to some interviewees, schools already work on the topic of climate change with students, contributing to increase awareness among the younger generations and, indirectly, older people. One interviewee also highlighted the role of local environmental organizations and public authorities.

There was also, in the interviewees’ discourses, a sense of urgency concerning climate action. This was often linked to the idea that such action must include adaptation (and the inclusion of public health concerns), for two reasons: some impacts are unavoidable or already irreversible and the activities that account for them cannot be extinguished:

Part of this problem will always be inevitable or irresoluble. In other words, we cannot stop the cities, we cannot stop the ships, we cannot stop the trains, we cannot stop the cars, we cannot stop the factories. However, and this has a lot to do with health, and with municipal management, we can improve the protective factors, such as physical exercise, healthy diet, good quality drinking water, as well as tackle risk factors, such as cardiovascular risk, substance abuse… there are various factors that we can leverage and then we could reduce the negative effects that climate change causes. (Interview 1)

The will to avoid future burdens also drives local adaptation. The possibility of avoiding or at least reducing the negative consequences of climate change for human health was seen by some interviewees as facilitating local climate change adaptation efforts as health is a topic to which both local decision-makers and the general population are sensitive:

(…) a way of raising awareness, (of) doing vertical pedagogy with policymakers, is to use health data, right? “But why do we need air quality measurement stations?” “Because there is a… here, look at the set of deaths that happen, right?” These things are not very close, but when we start to see, showing the data from Campanhã eastern Porto parish with considerable socioeconomic deprivation, where people die of cold, where people die, huh, the people who are the most vulnerable in this. Then this already affects them (policy makers) somewhat, right? (Interview 3)

(…) if there is a matter that is of unquestionable relevance for people and for the sustainability of communities etc., that issue is health. That’s why it had to be here on top, ok. (Interview 6)

Some of our interviewees told us about the increasing capacity of the local government to attract European funding to adaptation-related projects and about completed or ongoing actions funded by those mechanisms. According to one interviewee, the sustainable development goals defined by the United Nations also provide a favourable framework for the implementation of climate adaptation.

Zooming to the local level, we find several factors working as drivers of climate change adaptation. According to some of our interviewees, political awareness and commitment towards the issue by local decision-makers was a key driver to local climate change adaptation efforts. Another important factor, according to some interviewees, is the ability of several local stakeholders, including the municipal government, to work collectively to implement policies. Several interviewees stressed that local climate change adaptation in Porto adopts a multisectoral approach, including different municipal government departments and various municipal institutions. Several adaptation measures rely on the coordination among multiple actors, including stakeholders such as health professionals and health and climate change researchers, or in the optimization and exploitation of pre-existing networks and ties between different institutions and sectors. Both EMAAC and Metroclima share a participative approach, and their elaboration included the consultation of multiple stakeholders from Porto and the PMA, respectively.

Indeed, for a long time, the city of Porto has had what I call the network of the networks, that is, the health sector, the safety sector, the local government, and the social action, are all aligned in the same strategy. All work and build a network of services in the city, and a network of local policies, which allow each of the Porto residents to obtain the most benefit in each of the network nodes, and always nearby. In other words, the institutional and organizational barriers fell a little bit, as well as a discourse that was very common in the eighties: “That’s not my concern” interviewer: hum. That now changed to “everything is everyone’s concern.” (Interview 1)

This network approach, namely contact with actors from the field of health, has revealed itself as important for the inclusion of certain health concerns in the adaptation process.

(…) many of the awareness-related measures that we have worked, we couldn’t have done it without that approximation to the ACES primary care units cluster colleagues. Namely, we understood that there was a prevalence of skin cancer, excessive exposure crossed with climate predictions, this will probably get worse, and so we did not have any awareness action prepared. I mean, we never associated those aspects, right? We did not realize the importance of sensitizing people to use solar protection, for example, right? (Interview 3)

EMAAC also presents some of its measures as opportunities to reinforce institutional cooperation. This suggests that institutional cooperation and adaptation implementation may reinforce each other. Concerning this, the Municipal Council for the Environment (a local consulting body for the environment and sustainability that includes representatives of local stakeholders) is identified as a favourable element regarding the implementation of some of the adaptation measures.

The importance of having not just a city adaptation strategy but also a metropolitan adaptation plan was also pointed out by interviewee 3, who stated that, because “climate change does not exactly have territorial borders,” some issues require a shared approach within the PMA. But these collaborative ties are not exclusively local or metropolitan. As stated earlier, the origin of the Porto EMAAC is related to the ClimAdaPT.Local project, which was led by the University of Lisbon and offered important capabilities:

So, this strategy EMAAC also allowed us to be helped (interviewer: hum-hum, yes) integrated in a wider project, which was ClimAdaPT ClimAdaPT.Local, that ultimately promoted the capacitation of the city council technicians to elaborate strategies. It was done simultaneously, so it also allowed us to enjoy a little and do some benchmarking with other cities in the country. (Interview 3)

Equally important, according to EMAAC and several interviewees, is the volume of relevant information about the city, its climate, and its population’s health that is currently available or being produced. Some of this information was produced by the local government itself, while other was generated by other stakeholders, namely within academia. In the words of interviewee 3:

I think that the City Council, the municipality, has never known itself so well. It is very well supported by studies.

We identified several initiatives and policies that predate EMAAC or are mostly independent from it, but that also contribute to local adaptation: the Municipal Health Plan and the contingency health plans elaborated by the General Directorate for Health, the Plano de Ordenamento da Orla Costeira (a specific plan for the coastal area), the improvement of the thermal comfort and energy efficiency of social housing buildings and other urban rehabilitation programmes, the warning systems already in place, existing vulnerable populations social support networks, existing events about the environment and sustainability, and urban farming projects.

Another aspect facilitating local adaptation measures is the existing consensus about their co-benefits. This is the case of green spaces, which EMAAC identifies as beneficial for the quality of life, health, biodiversity, tourism, and the image of the city and for the protection of the coast from urban pressure.

Finally, EMAAC identifies the revision of legislation and several plans as opportunities to integrate adaptation measures in important policy areas. Particularly important is the revision of the Municipal Master Plan, which allows for the inclusion of several measures in this crucial planning document.

Health in the Local Adaptation Process: Obstacles to Local Climate Change Adaptation and Health Inclusion

Some interviewees identified obstacles related to aspects or areas whereas others saw strengths and drivers to local adaptation. While the idea that climate change awareness is growing and already significant, some interviewees consider that this awareness is still low, both among the general population and decision-makers.

I think that the consciousness is very low. And that, frankly, even today, when we talk about the need to promote this adaptation, people often, even responsible decision-makers, look at this speech with a bit of incredulity, thinking that we are not… there is not yet the notion that a country with a relatively temperate climate and a balanced geographical position, like Portugal, has a significant exposure to climate change. It still often seems like it’s someone else’s issue. (Interview 5)

According to Metroclima, the levels of knowledge in the PMA are also low, including among officials and professionals belonging to many of its local governments. The same document claims that climate change is downplayed in the PMA and found low levels of co-accountability, which are presented as obstacles to local adaptation.

Conflicting with the idea that local adaptation decisions are supported by thorough and accurate data, EMAAC identifies the need to improve the mapping of flood-prone areas, while Metroclima repeatedly states that there are gaps in the information about the climate of PMA and discontinuities in the temporal series because of changes in the location of the monitoring stations, while also calling for a better monitoring network, aspects confirmed by interviewee 2. According to some interviewees, the low level of disaggregation of the available data, including health data, is another problem as it hinders fine-grained knowledge about the geographical distribution of diseases, impacts, and vulnerabilities:

In the case of Porto, I have a big problem with the public health indicators, because I never have disaggregated information. It is possible that the reality of Eastern Porto - I do not know for sure because I do not have disaggregated information - is slightly different from the Foz area (affluent neighbourhood), or from Western Porto. (Interview 1)

Furthermore, some relevant data can be difficult to access. For example, according to one interviewee, actors from the health sector are sometimes reluctant, due to ethical regulations and professional culture, to share data with other parties intervening in local adaptation. Moreover, knowledge can be difficult to operationalize when planning in specific contexts.

There are also reports of difficulties in promoting dialogue and articulation between different actors, including the health sector. Communication between different actors, such as environmental organizations, academics, political decision-makers, the general population, and the above-mentioned health sector, is sometimes tense. EMAAC also identifies the need to articulate different actors as a factor conditioning the implementation of some of its measures, and, like Metroclima, detects difficulties in promoting cooperation between local governments to solve metropolitan-level issues. Interviewee 4 talked about a lack of a culture of institutional cooperation in Portugal that is locally translated and diagnosed a poor local culture of debate and public participation. While the local adaptation process seems to value and foster public involvement, the former is not exempt of difficulties, including communication difficulties and resistance to change, as stated in EMAAC.

Perceiving a low level of involvement of the health sector, another participant reasoned that this could be related to an overzealous view of the limits of institutional competencies, but also to limited resources, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic. Lack of resources and financial restrictions, in general, are also relevant issues according to EMAAC. Another interviewee considered that the economic difficulties that Portugal has been facing since the 2008 crisis limit mobilization regarding climate change. These limitations became more acute in the wake of COVID-19 and its social and economic consequences.

But we must not forget that we have been living through moments of economic crisis since 2008, and very strong ones. And therefore, the mobilization for these issues is hampered, isn’t it? (Interview 2)

An important obstacle is the short duration of political cycles, which introduces an element of uncertainty regarding long-term policies, since they may be disrupted by electoral change. This is an obstacle for the long-term process of local adaptation. Moreover, it renders the rhythm of politics much faster than the rhythm of scientific research.

So this is a barrier… the fact that we are talking of something that will occur in fifty years interviewer: right, and in hundred years. We begin to feel that no one questions that we are going to have a problem anymore, right? But, from there to taking truly disruptive options and investments during a political cycle, which is sometimes four years, I think this is a barrier, isn’t it? (Interview 3)

Some interviewees considered that climate change itself presents certain features that hinder adaptation, which is also stated in Metroclima. One of those features, as the above quote reveals, is its long-term nature. Climate change is also complex and surrounded by uncertainties. On the other hand, the process of local adaptation is necessarily negotiated between multiple interests and stakeholders, and, in a consolidated urban territory, has clear limitations imposed by the existing physical structure. Therefore, some measures may only be implemented at a limited scale, or may even be abandoned. Finally, the current mobility model in Porto, including several deficiencies in the public transportation system, was also identified as an obstacle both by EMAAC and some interviewees.

The analysed documents and interviews presented several other obstacles, although they are not as salient as the previous ones. These include technoscientific optimism, leading to a belief that human beings can manipulate nature with impunity; difficulties in changing the existing structures of the city (for instance, removing roads or adding green spaces); alarmism; lack of preventive measures for risk behaviours; lack of valuation of energy efficiency by the housing market; poor thermal comfort of houses; the need to reform public health service; the need to qualify city government professionals; technical difficulties concerning the monitoring of water resources and the improvement of thermal comfort; inequality; poor access to healthcare; undervaluation of the multiple benefits of green spaces; an ageing population; the distance between political power and common citizens; soil and water pollution; poor quality information circulating; and the criteria used to evaluate European funding applications that are sometimes detached from the Portuguese reality.

Discussion

The previous section reveals a planned local effort to promote local climate change adaptation and to address the health challenges posed by climate change. Diverse health-related risks are included in local adaptation planning and implementation; however, there are no explicit mentions of mental health concerns, which is consistent with previous research about local health-related adaptation 10. Also included is the elaboration of plans to deal with specific health-relevant climate change risks, such as natural risks, episodes of extreme temperatures, and sea level rise and coastal overtopping. Planning for disasters and emergency events is crucial, since their frequency and magnitude are expected to increase with climate change, as is their toll on public health 40. Multi-stakeholder involvement seems an important part of that effort. It also shows the steps taken towards policy integration in key areas such as water management, land use planning, and healthcare provision, as well as an effort to mainstream local climate change adaptation. Higher levels of policy integration and mainstreaming should lead to (and also result from) collective action 12. Because climate change vulnerabilities are transversal, adaptation must be integrated across policies to maximize synergies, prevent trade-offs, and address the relevant dimensions 41. This is also valid for the health dimensions of local adaptation: relevant vulnerabilities such as energy poverty and poor housing quality, social inequality, and ageing populations demand the integration of climate change and health concerns in broader policies. It is also worth noticing that many of these vulnerabilities are cumulative and amplify each other: firstly, individual health is directly related to the position in the social space: the more favourable the latter is, the better the former tends to be 42. Also, people with less economic resources will have a greater likelihood to live in inadequate houses and lack the resources to keep a healthy indoor temperature. On the other hand, health conditions, including chronic and degenerative diseases, have higher incidence on older people, especially in those from disadvantageous positions in the social space 43. Moreover, older people’s economic means often become more restricted 44. Thus, many health-relevant impacts of climate change, such as, for instance, heatwaves, are more concerning for these vulnerable people.

Like elsewhere 4, local adaptation is a somewhat recent issue in the agenda of this municipality. The process currently underway reveals health as a central theme for climate change adaptation. There is a clear recognition that climate change has, and will increasingly have, worrying health consequences. Health is the (sometimes indirect) subject of many specific adaptation measures. It also emerges as a major driver to adaptation, and a transversal theme that lies behind most adaptation options. This importance reflects the seriousness of climate change’s impacts on health even in cities located in affluent countries, which generally have ageing populations with a high prevalence of chronic diseases 7.

We presented a set of circumstances that act as drivers of local adaptation in Porto and of the inclusion of health in this process. Some of them are related to the local features of Porto, while others are indissociable from the broader context where the city is inserted.

Porto is the centre of the second largest and most populated urban area of the country. In addition to several private higher education institutions, it has a large public university and a large public polytechnic institute, and the education levels of its population are higher than the national average. It is also, within the Portuguese context, a municipality with high income and a large budget 45. Our results also suggest that Porto has considerable levels of social capital 46. Therefore, the local government should have a higher ability than most Portuguese municipalities to access both material and immaterial (e.g., knowledge and expertise) resources. Having access to relevant knowledge and information increases the ability to access material resources through funding opportunities. Indeed, European funding for local adaptation can be difficult to navigate 41, thus requiring expertise; furthermore, appliances to funding require some previous investment in risk and vulnerability evaluation and some knowledge about adaptation options 12. The case of Porto shows how access to certain resources is essential for local adaptation concerning health: access to knowledge and data through academics yielded important health information that informs the process, while access to the same type of resources through the health sector was at the origin of specific health-related adaptation measures. If, as the case of Porto suggests, available resources increase the ability to gather additional resources, this raises relevant issues of inequity across different cities 12.

Some specific funding opportunities are available to Porto because Portugal is a European Union (EU) member state. The EU has its own adaptation strategy and provides incentives to local adaptation, including funding opportunities 41. European policies provided an important push to the development of Portuguese climate policy 20, including climate change adaptation: following an EU directive, Portugal has a National Strategy to Adaptation to Climate Change since 2010 20,36. Later, in 2019, the country approved a National Action Plan for the Adaptation to Climate Change 18. Since the turn of the century, climate change adaptation has acquired increasing importance in Portuguese climate policy 36. As we mentioned, Porto’s EMAAC was one of 26 EMAACs developed under the ClimAdaPT.Local project, which was funded by the European Economic Area (EEA) Grants and Fundo Português de Carbono. Porto is also a member of the Covenant of Mayors and the Eurocities international networks, which offer opportunities for exchanging best practices and support capacity building for local adaptation policies 41. Previous research suggests that Portuguese municipalities belonging to international networks are better prepared to implement both mitigation and adaptation policies 12. Thus, local adaptation seems driven not only by local but also by the national and European contexts, although care must be taken when linking the former to the national and European adaptation plans: previous research was unable to identify a direct link between the European, national, and local adaptation strategies 4, while others have argued that local Portuguese polities lack adequate guidance from national and European strategies concerning adaptation 12.

Our results also highlighted a set of barriers 47 that the local adaptation process faces, sometimes in (seeming) contradiction with the drivers of climate change adaptation that we identified. Perceptions about climate change are important to adaptation, because they are related to climate action support 48, including support for difficult and unpopular measures 49. However, while growing awareness of climate change and its impacts, both among decision-makers and the population, was pointed out as a driver for local adaptation, several interviewees claimed that this awareness is still low. Some interviewees pointed out that, in Porto, like in Portugal in general, awareness is increasing but is still recent, which may help to understand this contradiction. Recent Eurobarometer surveys show high - and growing - levels of concern related to climate change and support to climate action among the Portuguese population 30. Yet several authors have also suggested that this does not translate into sound knowledge about the issue, nor in effective mobilization 20,49,50. Portuguese society seems to be characterized by high levels of climate change awareness but lower levels of knowledge and effective mobilization, which may help to explain the former dissonance in our data. This is certainly a relevant issue: we have seen that health is an important concern; however, if its relationship with climate change is not widely understood, its power as a driver for climate change adaptation will be reduced.

Likewise, the difficulties related to the participation and involvement of the general population may be explained by certain structural characteristics of the Portuguese society: Portugal has a fragile culture of political mobilization 51,52 and low levels of participation in environmental organizations. This should not be dissociated from a certain institutional resistance to the inclusion of citizens in the decision processes and a lack of public debate 50. Considering this, attempts to involve the public should meet difficulties. This will also hamper the power of health as a driver: the public may share a concern about it; it may even understand the relationship between climate change and health, but if there is no collective mobilization to push the issue, its effectiveness as a driver will be reduced, and its implementation might be socially unbalanced.

Another apparent contradiction in our data requiring an explanation is how an abundance of relevant data is seen as a factor that facilitates local adaptation by some interviewees, while other interviewees and the documents we analysed identify relevant data-related flaws, such as important limitations and discontinuities concerning climate monitoring, unsatisfactory levels of data disaggregation, and difficulties accessing important data, including both climate and health data. European local polities typically face important data gaps concerning future climate trends and extreme events, future socio-economic impacts of climate change, available adaptation options, and the costs and benefits of adaptation processes 41. Consequently, the limitations of the available climate data are unsurprising. On the other hand, we have seen that Porto, because of its dimension and available resources, has been able to gather data and knowledge to support its local adaptation policies. However, our data suggest it still faces some challenges in this matter. This could be the reason why available data are evaluated differently by distinct interviewees. The limitations concerning the existence, granularity, and availability of both climate and health data are important issues since continuous and accurate monitoring of both climate and public health variables is crucial to integrate health benefits in adaptation policies 7,9.

Finally, while the ability to promote a cooperative approach between different sectors and institutions, which lies, at least partly, in previous work and existing networks, was identified as a driver of local adaptation and part of its policy, the data also point out to difficulties in promoting joint action among multiple stakeholders. This contradiction may reflect actual tensions and ambiguities: concerning cooperation with the health sector, for example, we have collected accounts about difficulties concerning communication and data sharing but also accounts about successful moments of cooperation. It is important to consider that urban management has traditionally relied on a “siloed” approach, which may limit the integration of health considerations into urban planning and the participation of some key actors, namely, from the health sector, in the adaptation process 9. This stresses the importance of collaborative approaches and of cases of stakeholder involvement.

We also revealed some barriers that are relevant to many other cities, namely, the difficulty that quick electoral cycles pose when dealing with climate change and the complexity of adaptation processes, which must find an equilibrium between multiple interests and avoid having “losers.” This is an important issue as, even in affluent countries, deprived groups have less ability to adapt 6. The complexity, uncertainty, and long-term nature of climate change are barriers to political action and may undermine political leadership and commitment 41: uncertainty inhibits investing scarce resources in adaptation because the return will also be uncertain. This is all the more important considering that lack of appropriate leadership is a barrier to adaptation 41,47. Additionally, the sociodemographic trajectory of the population, which contributes to shape health vulnerability, is also uncertain 6. Climate change requires thinking and acting in the long term, which may be hardly compatible with short political cycles (in Portugal, local governments are elected for a term of 4 years). Long-term measures implemented by a local government may be disrupted by the next elected local government; therefore, it is easier to implement reactive, instead of preventive, measures. This barrier is even more significant when awareness is low and there are gaps in the available knowledge and data 41. Better data may foster political commitment and action by reducing uncertainty, while greater public awareness and knowledge may favour support to difficult measures. Our results suggest that awareness about the health risks of climate change may work as a means to contour this barrier as it is a topic likely to resonate with both decision-makers and the general population.

The need to balance multiple interests in local adaptation implies that some adaptation options end up being abandoned. This may have two pernicious consequences: firstly, as some measures are dropped, local adaptation might end up being less ambitious than what was envisioned by initial planning. Secondly, because social actors have unequal abilities to push their interests forward in the public arena, disadvantaged groups - who are also more vulnerable to the negative effects of climate change - may become “losers” of this process. Adaptation implies a careful equilibrium that may require important trade-offs 41, including potential health trade-offs 9. As adaptation may carry health benefits but also aggravate health risks and inequalities, this is also important when considering health concerns in local adaptation processes. The extensive involvement of stakeholders and adequate communication may help to prevent this undesirable outcome 9,12.

Our research has some strengths and limitations that must be considered. Beginning with the strengths, we presented a detailed, nuanced, and context-sensitive analysis about the inclusion of public health concerns in local climate change adaptation planning. We have payed attention to how different contextual factors (local, national, and international) may contribute to shape relevant local policies. Furthermore, our investigation contributes to increasing our knowledge about an under-researched topic 53.

Considering the limitations of the study, our data would have been enriched if we also interviewed stakeholders from the environmental movement. We also did not analyse sectorial plans that might be relevant to local adaptation change and the inclusion of health aspects in the former, even if that is not their main focus (e.g., the Municipal Health Plan). It could also have been valuable to evaluate the level of implementation of the measures presented by the plans we analysed.

To conclude, the case of Porto reveals the crucial importance of health to local adaptation processes: it is both an essential issue and a powerful mobilizing topic. Local adaptation is shaped by factors situated in different contextual levels. Growing awareness to climate change and national and international adaptation incentives present important opportunities for local adaptation initiatives. Existing local networks are also of crucial importance. However, both climate adaptation and health are transversal issues, requiring mainstreaming and policy integration. To achieve this, and to surpass the complex obstacles that both local adaptation and the inclusion of health aspects in the former present, a strong articulation between different levels of governance, as well as an inclusive approach involving local stakeholders from different areas, including the population, is needed. It is important to acknowledge that climate change is a challenge of great complexity. To face it, local polities will have to make the best of their resources, including using social capital to multiply resources and involve multiple stakeholders to prevent undesirable trade-offs and imbalances. Even though we conducted a case study, our results may be relevant to other cities, especially to coastal Mediterranean cities, which should share some vulnerabilities and obstacles with Porto. This relevance should increase for such cities that are also part of EU member states.

Statement of Ethics

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Public Health of the University of Porto, Approval No. CE20175. Due to COVID-19-related restrictions and recommendations concerning personal contact, the interviews were conducted over the Internet, using the Zoom platform. As a result, informed consent in oral form was collected at the beginning of each interview and documented through audio recording.

Author Contributions

José Pedro Silva: study design, data acquisition, curation, analysis, and interpretation, writing - first draft, writing - reviewing and editing, and approval of the final version; Gloria Macassa: conceptualization, study design, writing - reviewing and editing, and approval of the final version; Henrique Barros: writing - reviewing and editing and approval of the final version; and Ana Isabel Ribeiro: study design, data analysis and interpretation, writing - reviewing and editing, and approval of the final version.

Data Availability Statement

Both the Municipal Climate Change Adaptation Strategy and the Metropolitan Plan of Climate Change Adaptation are public documents and can be found online. The interview transcripts are confidential to preserve the anonymity of participants and the confidentiality of interviews.