Introduction

Extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma (ESS) is an unusual, aggressive primary tumor of the deep soft tissues with a high rate of metastasis1. It was first described in 1969 as a paravertebral “round cell” tumor similar to Ewing’s sarcoma2,3 caused most often by a translocation t(11;22)(q24;q12) and t(21;22)(q24;q12), resulting in the establishment of the EWS-FL1 fusion gene and overexpression of the FLI protein-14,5.

ESS is prevalent in men and in the second decade of life at the time of diagnosis6,7. Its most common symptom is a fast-growing mass, with an average progression time of 5 months before diagnosis8, mainly in the paravertebral spaces.

This report is about a 21-year-old female patient with a relapsed tumor with rapid and aggressive growth, surgically approached in another service, and without histopathological analysis, so the scope of this report is to highlight the importance of the diagnostic method and elucidate possible differential diagnoses in the clinical management of the tumor.

Case report

A 21-year-old previously healthy woman was referred to a specialized dermatology service due to an asymptomatic nodule in the right lumbar region that had been growing rapidly and progressively for 2 months (Fig. 1A and B). The patient reported that she was rushed to the emergency department and underwent surgical exercises at the beginning of her condition. Ten days after the procedure, she presented pain, local edema, and a relapse of the lesion, being treated with two consecutive percutaneous drainages.

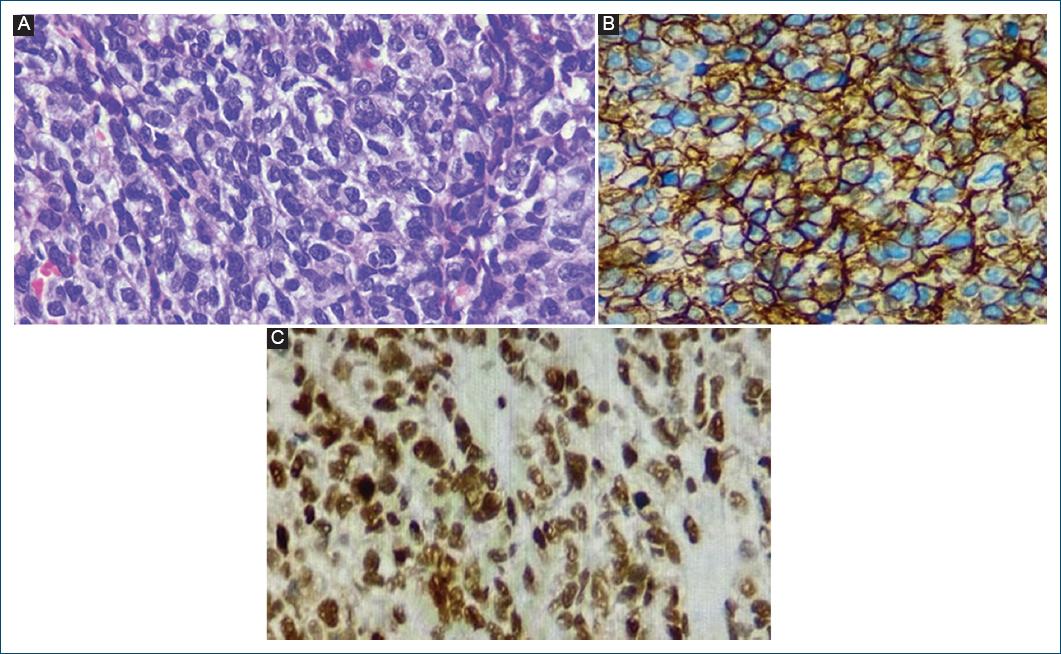

Dermatological examination revealed a 10 × 10 cm solid nodular lesion with a smooth, erythematous, and telangiectatic surface, with areas of ulceration and fistulization located on the right flank. An incisional biopsy was conducted, and the histopathology confirmed an undifferentiated malignant neoplasm with dense, homogeneous layers of small, round blue cells, a nucleus with regular chromatin in large proportion when compared to the cytoplasm, mitotic patterns, as well as extensive necrotic areas infiltrating the hypodermis (Fig. 2A). Immunohistochemistry highlighted diffuse positivity for CD99 (Fig. 2B) and FLI-1 (Fig. 2C) and was negative for muscle antigens (1A4 and desmin), CD34, S100, EMA, and CD30, therefore supporting the diagnosis of extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma.

Figure 2 A: histopathology showing a cluster of small round blue cells. Hematoxylin and eosin, 400×. B: CD99-positive diffuse in the membrane. C: FLI-1-positive diffuse in the nucleus.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed an expansive mass on the posterior wall of the right thoracoabdominal transition. The extent of the lesion involved only soft tissue adjacent to the perivertebral muscle tissue, measuring 8.3 × 10 × 4.6 cm, with vascular infiltration and contrast enhancement around it. The MRI also disclosed that it did not involve bones. After confirming the diagnosis, the patient was referred to Clinical and Surgical Oncology and underwent extensive surgical excision, with reconstruction using a transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous graft and flap (Fig. 1B). She is currently being treated with chemotherapy (vinblastine, vincristine, and cyclophosphamide).

Discussion

Ewing’s sarcoma is the second most common malignant bone neoplasm in young adults, after osteosarcoma6. ESS, on the other hand, is an uncommon primary tumor of the deep soft tissues, corresponding to 15-20% of cases in Ewing’s sarcoma family of tumors9.

ESS is more common in men, with an average age of 17 at the time of diagnosis6,7. Its main clinical finding is a fast-growing mass, with or without local pain, and an average size of 2-3 cm7. The main sites of extraskeletal involvement include the paravertebral spaces, followed by the lower extremities, and then the head and neck10. Poor prognostic factors are age over 14 at the time of diagnosis, primary tumor volume over 200ml, and the presence of metastasis1.

At present, the diagnosis of ESS is mainly based on pathological and immunohistochemical findings. Histologically, it is composed of layers of small, round blue cells with round, hyperchromatic nuclei and scarce cytoplasm. On immunohistochemistry, it is positive for CD99 (a cell surface glycoprotein encoded by the MIC2 gene) and FLI-1, which has greater specificity than CD9911.

In this scenario, imaging is essential to evaluate the location of the tumor and its extent, the possibility of metastasis, and, consequently, the organs involved, thus guiding appropriate clinical management. The MRI findings coincide with recent studies that characterize the radiological features of the disease, such as low signal intensity in T1, similar to muscle, high intensity in T2, and heterogeneous enhancement12,13.

The first course of treatment is surgical excision of the tumor, combined with chemotherapy. Radiotherapy is used in cases where the patient is unable to undergo surgery or still has positive margins after resection. The 10-year survival rate is 91%7.

The diagnosis of ESS is challenging due to its unusual prevalence and the various differential diagnoses that subcutaneous nodules have. High awareness is required in the case of circumscribed, fast-growing lesions in the paravertebral regions and lower extremities of young people. Due to their aggressive nature and high rate of metastasis, diagnosis should be carried out promptly. Histopathological analysis is the gold standard and cannot be ignored. Imaging, on the other hand, evaluates and monitors tumors and metastases. Complementary assessment and correct treatment help with early diagnosis, improve prognosis, and give patients a better quality of life.