Introduction

Infant mortality is an important collective health data, as it is an indicator that represents the quality of care provided to mothers and children born alive in a territory, reflecting the socioeconomic and health development conditions and access to available resources to this end. In addition, infant mortality rates also document the risk of a live birth dying in the first year of life and are used for planning, managing, and evaluating policies and actions of maternal childcare.1

The reduction of infant mortality is on the United Nations (UN) agenda, with the goal of eliminating infant death from preventable causes by 2030. Between 2007 and 2017, 511 thousand children died in Brazil; of these, more than 338 thousand deaths were due to preventable causes.1 Among these stands out the sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), which accounts for 1,762 deaths in children under one year of age observed between 2007 to 2017 in national territory.1 In 2018, 136 children under one year died from SIDS, and 39 from suffocation and accidental strangulation in bed.2

SIDS is defined as unexpected death in children under one year of age during the sleep period without the possibility of determining the cause, even after a thorough investigation, being the most prevalent cause of infant mortality in developed countries and the third leading cause of infant mortality in general.3-5 A classic epidemiological study by the American Academy of Pediatrics reported that babies undergoing SIDS were, on average, eleven weeks old, with a peak incidence of SIDS between two and four months of life and 90% of cases occurring before the age of six months.6

Regarding the main causes of SIDS, the literature indicates biological factors, such as pregnancy complications, prematurity, and low birth weight; family factors, including babies not breastfed, age of the mother, multiparity, and unhealthy maternal habits; and cultural factors, such as sleeping position, bed environment (surface, loose bedding, presence of objects), shared bed use, and prenatal care.3,4,7-9 Socioeconomic disadvantage, with low education and maternal income, are also pointed out, linked to the lack of access to prenatal care.10

Despite the complexity of this phenomenon, advances have been made in approaches to prevent SIDS , with the most useful being the management of the supine sleeping position (belly up) and rigid sleeping surface.11 One study showed that information about children’s/babies’ correct sleeping position is often disseminated through social media, with only 25% being conveyed by health professionals.3 This data is alarming since the lack of information regarding the topic eventually causes a delay in the implementation of preventive measures aiming to reduce the number of SIDS cases.12 Health education, through the development and dissemination of public maternal health policies to guide health teams, parents, family members, educators, and caregivers, is highly relevant in this setting.

In view of the above, this study sought to investigate the knowledge of puerperal women admitted to a public teaching hospital about sudden death syndrome in babies and its preventive measures, aiming to support the development of educational and preventive measures at hospital level.

Materials and methods

This was a qualitative descriptive study of frequency of responses carried out in the context of a Multiprofessional Residency in Health program in urgency and emergency setting of a public teaching hospital in the countryside of Paraná, Brazil.

All puerperal women admitted to the maternity ward of the referred hospital on the days of the extension project from October to December 2019 were included.

Semi-structured interviews with an average duration of ten minutes were carried out using a semi-directed script based on the Brazilian Society of Pediatrics’ recommendations for prevention of sudden death.11 The variables assessed included age, skin color, marital status, school education, profession, working status before pregnancy, number of children, history of abortion or stillbirth, number of prenatal consultations, gestational age at the beginning of prenatal care, type of delivery, and smoking and alcohol consumption habits during pregnancy.

To investigate women’s knowledge of sudden death, the following initial questions were posed: “Have you heard about sudden death? Could you explain what you understand about sudden death?” To assess women’s knowledge of preventive measures for sudden death, the following questions were also posed: “In your opinion, what is the best position for your baby to sleep? For what reason?”; “Regarding your baby’s ideal sleeping habits, do you believe it is better for him/her to sleep alone or in the same bed with parents? For what reason?” and "Do you believe the baby should sleep with a toy or without a toy, with a pillow or without a pillow? For what reason?".

Women were approached during hospitalization, at a time considered favorable and without prejudice to routine care. After trained researchers explained the study objectives, women were invited to sign a formal consent for collection, analysis, and dissemination of the analysis of retrieved data. After data was collected, the researchers provided training regarding preventive measures for sudden death, based on recommendations of the American Society of Pediatrics.13

Participant interviews were fully transcribed and handled through a qualitative data analysis technique, and descriptive statistics were obtained for all closed questions.

This study was conducted in accordance with the rules of Resolution 466/2012 of the National Health Council and the Declaration of Helsinki and received ethical appraisal from the Brazilian Research Ethics Committee under the CAAE protocol: 122001619.6.0000.0105, decision: 3.297143.

Results

A total of 61 puerperal women with an average age of 25 years were included in the study. Most were single (52.5%), had a single child (41%), had not completed high school (49.2%), had been working prior to pregnancy (65.6%), and had a family income of up to one minimum wage (29.5%) or between one and two minimum wages (29.5%). Regarding general health aspects, 19.7% of women had seven prenatal consultations, 29.5% started prenatal care at eight weeks of pregnancy, and 73.8% had a normal delivery. Most women had not smoked (86.9%) or consumed alcohol (82%) during pregnancy.

The analysis of women’s knowledge of sudden death showed that 42.6% had no knowledge of the topic, 32.8% had heard about it but did not know how to explain it, and 24.6% linked the phenomenon to cardiac arrest or suffocation during the baby's sleep.

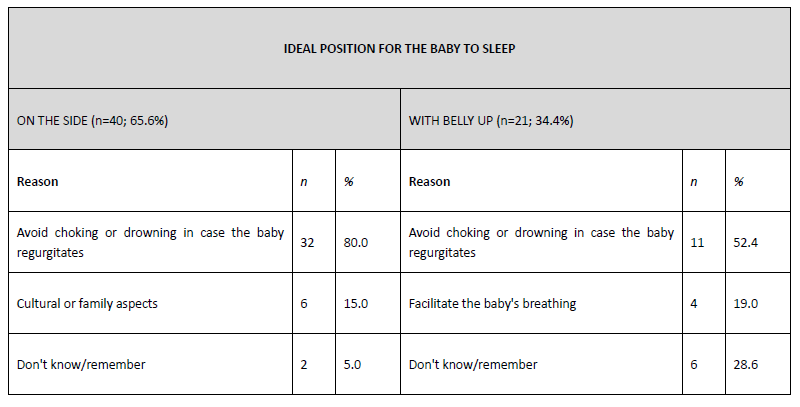

Tables 1 and 2 depict women’s perceptions regarding sudden death in childhood and preventive measures, with indication of the respective prevalences. The results showed that 65.6% of women answered in favor of the lateral sleeping position, and 34.4% considered that the belly-up sleeping position was the most correct.

Below are transcripts of women’s answers, indicating choking or drowning prevention as the main reasons for the choice of the baby’s lateral (LP) or belly-up (BP) sleeping position:

“[...] I prefer it aside, because if she chokes it is easier to throw what is in her mouth.” (LP, 29 years old)

“On her side, so as not to drown, because on her back she will swallow again and drown.” (LP, 39 years old)

“On the side, right? Because if you throw up you will already play. And if you have your back, you’ll swallow again.” (LP, 28 years old)

“In the past, it would be on the side, but today I know it’s belly up, according to what I saw, if he vomits, it makes noise, I don’t know if it’s better or not. But he does not run the risk of drowning because we are going to listen and he throws it out a bit”(BP, 36 years old)

“[...] so they told me it’s belly up, without a pillow, or anything, I think it’s like that. I think it’s not to choke.” (BP, 21 years old)

“Belly up and head turned to the side, so as not to be in danger of drowning.” (BP, 22 years old)

Other reasons pointed out for the choice of the baby’s sleeping position included cultural and family aspects and the argument that the position would facilitate baby’s breathing.

“Belly up. Because this way the air circulates and it is better to breathe. ” (BP, 22 years old)

“[...] my mother always told me that the best is on the side. (LP, 27 years old)

“Beside. I did that with my other daughter already” (LP, 22 years old)

“I think that on the side, right? I’ve always heard that it’s like this.” (LP, 17 years old)

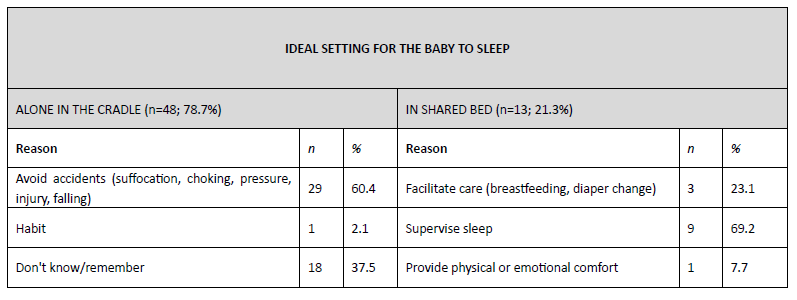

Regarding the ideal setting for the baby to sleep, 78.7% of puerperal women believed that the baby should not share the bed with parents, but most women with other children said that they shared the bed with the baby (52.9%). Ninety-five percent of women stated that the baby should sleep without a toy, and 53.3% thought that newborns should use a pillow. The same answers were provided regarding the other child, with 94.1% of women reporting not leaving toys in the cradle and 64.7% using a pillow.

Below are quotes of the main reasons provided by women regarding the ideal setting for the baby to sleep (A - alone in the cradle; SB - in shared bed).

Home accidents were the main reason reported by mothers who believed that the baby should sleep alone in the crib, with no mention to the use of pillows or toys.

“Alone, because it is dangerous to roll over the child or fall. Without a toy and without a pillow, the toy is dangerous for them to put in their mouths.” (A, 38 years old)

“Alone, because there is no risk of me lying on top of her and she has more autonomy to move. No pillow and no toy, because it’s ideal, you know, it’s used for convenience.” (A, 29 years old)

“[...] We prefer her alone in the crib, but on the side of our bed, to avoid suffocation and the things that can be avoided. At first, no pillow.” (A, 24 years old)

“The best thing is in the cradle, so that there is no danger of drowning the baby or rolling over and hurting. Better without a toy, because they put it in their mouths and then they’ve seen it ... Now, pillow, I think who has to use it, to make it better for them to sleep.” (A, 27 years old)

On the other hand, ease of supervision of the baby’s sleep was a determining factor for mothers who supported bed sharing, who also showed no consensus regarding the use of pillows or toys.

“With me, it’s easier to take care. Toy I think is dangerous, then it is better without. Pillow, when it is small, better not to use it.” (SB, 23 years old)

“While he is young, the best is with his parents, you know, because he is afraid of drowning, and with us, then he wakes up and sees. I think without a toy and with a pillow, because it looks better for them, right?” (SB, 19 years old)

“In bed with us, it’s easier to take care. The toy helps to stay calm, and with a pillow.” (SB, 23 years old)

Discussion

This study evidenced a low level of adherence of puerperal women to prenatal consultations, with 19.7% attending a total of seven consultations during the current pregnancy. Although the ideal number of prenatal consultations is controversial, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a minimum of eight consultations for pregnant women with normal risk.14 Low adherence to prenatal consultations is one of the risk factors for SIDS reported in the literature.15

Studies show that non-adherence of pregnant women to prenatal care is strongly linked to socioeconomic factors, especially education and income. The underprivileged population tends to be assisted for failed and late pregnancies, normally starting after the first gestational trimester, which is also linked to access to prenatal care and quality of maternal health care, involving social support and health teams.10,16-18 Factors such as maternal age, number of children, absence of a spouse, unhealthy habits during pregnancy (as alcohol or other drug consumption), and lack of appreciation of prenatal care, among others, have also been associated with non-adherence to prenatal care.10,18 These findings may partially explain the low adherence of puerperal women to prenatal consultations observed in this study, as the study sample was mainly composed of women with low educational background and income. Still, it cannot be ruled out that the low adherence to prenatal care observed may be due to disruption of the actions of local and regional health services aimed at this population.

To improve maternal and childcare networks and reduce morbidity and mortality rates, the Brazilian Ministry of Health established Rede Cegonha.19 This initiative has the purpose of changing the whole process of care during pregnancy, with emphasis on improving the structure of health services to achieve an articulated care network, improving the environment of health services (basic health units and maternity units), linking pregnant women to maternity, and expanding and technically qualifying the health teams involved. The absence of bonding between health professionals and subjects also has an impact on their adherence to prenatal care. Pregnant women tend to develop high expectations towards the care provided, and when they do not find cordiality, respect, and attention, end up abandoning care for not meeting their expectations.10

Social support, which includes family support and support by the entire health team, goes beyond the positive influence on adherence to prenatal care, also encompassing the choice of habits and attitudes related to baby care. In the present study, most puerperal women were unaware of the phenomenon of sudden death syndrome in babies and had misconceptions about their preventive measures. Family influence may have a beneficial impact in this regard, as shown in a study where mothers were discouraged by their relatives from practicing co-bedding.20 On the other hand, this study also showed that the family can have a negative influence, namely in the choice of the baby’s sleeping position, with 15% of the choices of the lateral sleeping position being due to cultural or family influence. A similar result was found in another study, where more than 10% of mothers reported that the adoption of the baby’s lateral sleeping position was influenced by family and friends.21 This highlights that the family should be included in the health education process regarding the ideal baby’s sleeping position, maximizing the likelihood of women adhering to health recommendations.

Another relevant aspect in the literature is that more than 58% of mothers who opt for the supine position (belly up) report having received this guidance from a health professional, confirming the relevance of these professionals in the dissemination of guidelines for maternal and child health.21

In the present study, 65.6% of women stated that they were in favor of the baby’s lateral sleeping position, which represents a high percentage of women with an incorrect perception of the ideal baby’s sleeping position. In developed countries, the adoption of the ‘belly up’ position for children’s sleep (considered correct) is already a common habit and, together with a low prevalence of SIDS, is linked to better socioeconomic conditions.22 According to the same study, higher education and higher family income are associated with greater security in the adoption of the supine (belly up) position. It is worth mentioning that women interviewed in the present study had a low educational and socioeconomic background, which may predispose to greater resistance in the adoption of preventive measures to prevent SIDS.

The incidence of SIDS has decreased dramatically in countries that adopted policies to encourage the belly-up position. The first campaigns took place in Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. In the United States, the incidence of SIDS decreased by 50% after 1992, when the American Society of Pediatrics recommended the adoption of the supine sleeping position.23

Studies have shown that sleeping in prone position (belly down) substantially increases the likelihood of SIDS. An analysis of case-control studies showed an odds ratio for SIDS between 2.3 and 13.1 when using the prone to the detriment of the supine position.21 Although in the present study most mothers reported a preference for the side position, this should be avoided since the probability of the baby rolling to the prone position when lying on the side is greater than in the supine position.24

Regarding mothers’ perceptions of the ideal setting for the baby to sleep, most believed that it would be alone in the cradle, even though most reported having shared the bed with the baby in subsequent pregnancies. The establishment of a mother-child bond and maternal instinct, tiredness, fear, and care, as well as greater paternal participation, have been identified as key factors for adopting co-bedding, even if mothers are aware of formal guidelines.20 The testimonies retrieved in this research indicate the ease of breastfeeding and diaper change, sleep supervision, and emotional comfort as reasons for shared bedding.

A meta-analysis revealed a 2.89-fold increased risk of SIDS in babies who share the bed with parents compared to babies who do not, with an even greater risk for children under the age of three months.23 Bed sharing can increase the risk of SIDS by up to 15 times in children with additional risk factors (bottle use, for example) and with parents having smoking and alcohol consumption habits.23 It is crucial to provide professional guidance to these families as a way to change the social paradigm of the need for co-bedding for the establishment of a bond between mother and child. Studies stress the importance of physical care, especially breastfeeding and bathing, for newborns, but also of affection and exchange of glances as rich opportunities for implementing and increasing the interaction between mothers and sons.10,20

In this study, 53% of mothers reported using pillows for their babies. According to the literature, loose bedding accessories, such as blankets, bedspreads, pillows, plush toys, and sheep fur, increase the risk of SIDS by up to five times, regardless of the baby’s sleeping position. Death is believed to occur due to covering the baby’s head with these objects and consequent breathing difficulty and asphyxiation.9,25 These risk factors are particularly important in older babies, who can roll over objects.23 Multiple environmental and modifiable risk factors for SIDS have been reported (sleeping position, sleeping environment, smoking habits of parents), but interpreting whether certain evidence confirms accidental asphyxia is challenging and not fully conclusive.26

In view of this, it is crucial that health professionals emphasize the application of SIDS guidelines, especially in prenatal care and childcare, and foster strategies that positively contribute for puerperal women to mitigate risk factors for their children.5

This work has limitations that should be considered, such as the fact that it only included a single center and its small sample size. As strengths, it allowed to investigate the knowledge of mediate mothers about SIDS and its preventive measures, supporting the optimization of health education strategies for pregnant women, puerperal women, and the general population.

Final considerations

This study documented a low level of knowledge of puerperal women about SDIS and the practice of risky behaviors, such as positioning the baby on the side, using pillows, and sharing the bed with the baby. It also allowed to identify ease of care and supervision and physical and emotional comfort as main reasons for bed sharing with the baby.

In view of this data, educating parents and family members about prevention of sudden infant death should be a priority, with recommendations for accommodating the baby in the supine position in a proper and free sleeping space, especially during the first year of life, and for the baby to sleep in the same room as parents, but in the crib. These are simple preventive measures that should be initiated in the prenatal period and extended to the puerperium, as they can have a great impact on SIDS prevention.

Authorship

Emily Pavlovski de Paula - Writing - original draft

Cristina Berger Fadel - Methodology; Formal Analysis

Melina Lopes Lima - Data Curation; Investigation

Fabiana Bucholdz Teixeira Alves - Writing - review & editing

Luciane Patrícia Andreani Cabral - Writing - review & editing

Everson Augusto Krum - Writing - review & editing