Introduction

Nijmegen breakage syndrome (NBS) is a rare genetic disorder (1:100000) caused by mutations in the NBN gene, which is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern.1 With more than 60 variants described, the NBN gene, located on chromosome 8q21, is the only gene identified to date in the genetic basis of NBS.2 The protein product of the NBN gene is nibrin, which plays a key role in regulating the activity of proteins involved in the end-processing of normal and mutated DNA double-strand (DDS) breaks caused by ionizing radiation.2),(3 When DDS breaks are not repaired, they result in genomic instability, gene mutations, or chromosomal rearrangements that can lead to malignancy, particularly of lymphoid origin.4 Nibrin also plays a role in lymphocyte maturation and immunoglobulin class switching, resulting in immunodeficiency characterized by recurrent sinopulmonary infections and increased radiosensitivity.

The main clinical feature of NBS is progressive and severe microcephaly, which affects the facial phenotype, resulting in a prominent midface, sloping forehead, and retrognathia.2 The nose is usually long and beaked, but may also be upturned with anteverted nostrils.2 Mild to moderate intellectual impairment is often present, and female patients usually develop primary ovarian insufficiency.2

The diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion and is confirmed by molecular genetic analysis.

Case reports

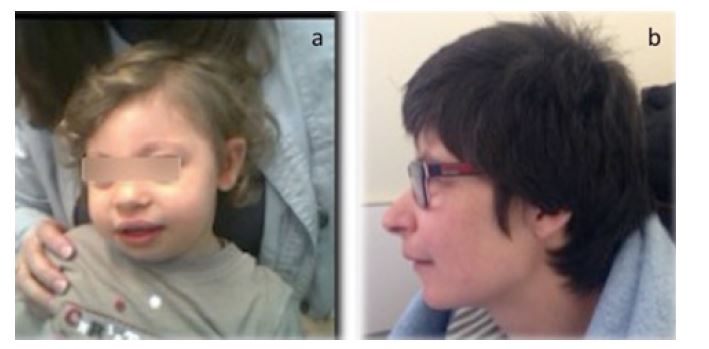

Case 1. An 18-month-old male of Ukrainian ancestry was referred to the hospital for severe microcephaly noted at birth. He presented a “bird-like” face (Figure 1a) and a café au lait spot on the right lumbar region. He had severe lymphopenia (686/mm3) with low CD4+ counts (CD4 375/mm3; CD4% 28.4; Table 1). There was no relevant family history and the parents were not consanguineous. Molecular genetic analysis revealed a homozygous pathogenic variant, c.657_661delACAAA(p.Lys219Asnfs*16), confirming the diagnosis of NBS.

The child maintained regular follow-up. He is currently six years old, has moderate speech delay, and is receiving speech therapy and global developmental stimulation. Microcephaly was progressive (less than the 3rd percentile, standard deviation -4.86) and the boy maintained severe lymphopenia with low CD4+ counts. Prophylactic cotrimoxazole was administered during the first three years of life. To date, he had no severe infections or signs of malignancy.

Case 2. A four-year-old girl was referred to the immunodeficiency center for recurrent respiratory infections. She had severe microcephaly (below the 3rd percentile, standard deviation -3.79), prominent midface, sloping forehead, receding mandible, and long, prominent nose (Figure 1b). The initial study revealed immunoglobulin deficiency and lymphopenia with low CD4 counts (Table 1). At the age of five, she was hospitalized for severe autoimmune hemolytic anemia, with good response to steroids. She had a favorable course throughout childhood and adolescence, with moderate intellectual disability and recurrent respiratory tract infections, which were treated in the outpatient setting. The girl was transferred to the adult immunodeficiency clinic at the age of 18 years, clinically stable.

At the age of 33, she presented with severe hemolytic anemia and severe lymphopenia and cryoglobulinemia, and was diagnosed with lymphoplasmocytic lymphoma. She was treated with a chemotherapy regimen (five cycles of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, and prednisone), with initial clinical remission. Six months later, a control computed tomography (CT) scan showed pulmonary relapse and the girl was started on a new chemotherapy regimen (four cycles of rituximab and bendamustine). She experienced clinical deterioration since cycle four, and a new biopsy of a mass lesion confirmed progression to high-grade diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. She was started on palliative treatment with cyclophosphamide and rituximab, with no response and a fatal outcome in four months.

The patient fulfilled clinical and analytical criteria for NBS and had several chromosomal abnormalities: 46,XX,t(2;13)(p21;q14),t(6;10)(q21;p15),t(7;11)(q32;q23.2). Molecular genetic testing for the most common abnormalities in the NBN gene at that time (including the founder mutation in exon 6, c.657_661del5) was negative. Genomic array (array-CGH) showed the presence of the 6q23.1-q23.2 deletion associated with lymphoplasmocytic lymphoma.

Discussion

The diagnosis of NBS is based on characteristic clinical manifestations, chromosomal instability, increased cellular sensitivity to ionizing radiation in vitro, cellular and humoral immunodeficiency, and homozygous pathogenic variants in the NBN gene.

Patients have a high susceptibility to infections, usually involving the respiratory tract (chronic sinusitis, recurrent bronchitis, pneumonia). Opportunistic infections are also common. Early diagnosis of NBS is important to prevent severe recurrent infections.

There is no specific treatment for NBS. Intravenous immunoglobulin may be given if immunoglobulin levels are low, and appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis may be instituted.

Unnecessary exposure to all forms of ionizing radiation for diagnostic purposes should be avoided unless absolutely necessary. Because of the high sensitivity to radiation treatment and chemotherapy, the radiation dose should be limited and chemotherapy protocols should be tailored to individual tolerance.2,4 In these patients, it is reasonable to reduce the chemotherapy dose by up to 50%, especially with anthracyclines, methotrexate, alkylating agents, and epipodophyllotoxins. The use of monoclonal antibodies and kinase inhibitors or bone marrow transplantation with reduced-intensity conditioning can be considered in selected cases to replace radiotherapy and some antineoplastic agents, as performed in Case 2.1,4

The major complication associated with chromosomal instability is the development of cancer, primarily of lymphoid origin. As many as 40% of malignancies are diagnosed before the second decade of life, and the most common types are non-Hodgkin lymphoma, predominantly diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma.4 Patient prognosis remains poor.

Malignancy should be carefully assessed, as it may occur several decades after diagnosis. The patient in Case 2 presented with lymphoma in the third decade of life, with an initial remission followed by a fatal course, which is common in these patients. Early diagnosis must be made by examinations that do not involve the use of ionizing radiation. However, this patient underwent two chest X-rays and three CT scans between diagnosis and follow-up because these studies are more accessible than magnetic resonance imaging. The impact of this amount of ionizing radiation on the final outcome is unknown.

The present two cases illustrate the importance of close and long-term follow-up of NBS patients from childhood to adulthood, as some comorbidities may be prevented or reduced with early treatment. In addition, genetic counseling should be offered to parents of affected patients, as NBS is an autosomal recessive disorder and prenatal testing for increased risk pregnancy or preimplantation genetic diagnosis for NBS can be performed.2