Introduction

Acute respiratory infections are the leading cause of pediatric hospitalization worldwide.1 Bronchiolitis, asthma, and pneumonia are the primary causes of hospital admission and have a significant impact on hospitalization costs.2 Viral infections are the main etiology of these diseases and are also a major cause of morbidity in infants and children.3 Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), rhinovirus (RV), and influenza virus are the most common, but other viruses also play a critical role in these diseases.4 Although most respiratory viral infections occur throughout the year, there is a clear seasonal variation for certain viruses.5

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was first detected in December 2019 in Wuhan, China.6 On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) a pandemic.7 The first case in Portugal was reported on March 2, 2020.8 In response to the pandemic, general non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) were implemented to prevent and control SARS-CoV-2 transmission, including social distancing, use of protective equipment (masks and face shields), reinforcement of personal hygiene measures (hand hygiene and respiratory hygiene/coughing etiquette), and environmental hygiene measures.9) These measures were not specific to SARS-CoV-2 and thus had a potential impact on the transmission of other respiratory viruses as well.10

The initial adoption of NPIs coincided with the end of the 2019-2020 winter season in northern hemisphere countries, where published data showed a premature end to viral seasonality, a significant decline in infectious diseases, and a reduction in medical visits (<68%) and hospital admissions (<45%).11,12 In the southern hemisphere, measures to mitigate the transmissibility of the new virus were implemented prior to the local peak of RSV and influenza infections. Data showed historically low levels of RSV and influenza, as well as a decline in the detection of respiratory viruses and related hospital admissions, immediately following the implementation of COVID-19-related restrictions.13-15

The SARS-Cov-2 pandemic and the implementation of NPIs were associated with a lower transmission of all airborne viruses.16 Additionally, the higher incidence of the novel coronavirus may have competed with other viruses, potentially leading to a decrease in the overall incidence of viral respiratory infections.17 Taken together, these factors may have contributed to changes in the rates and characteristics of pediatric hospitalizations for respiratory infections.

The aim of this study was to compare pediatric hospitalizations for respiratory infections before and after the emergence of SARS-CoV-2. The specific objectives were: a) to analyze the number, type, and seasonality of respiratory infections; b) to describe the microbiological agents associated with respiratory infections; and c) to evaluate the type of clinical approaches used, including diagnostic tests and therapeutic measures.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

This was an observational retrospective study of hospitalizations due to respiratory infections (non-SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV-2) in the pediatric ward of Centro Materno-Infantil do Norte (CMIN) at Centro Hospitalar Universitário do Porto (CHUPorto), Portugal, between April 2018 and March 2021. The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of CHUPorto. Informed consent was waived, as this was a retrospective study using data solely from electronic clinical records. The STROBE statement for reporting observational studies was followed.18

Participants, data collection, and variables

Inclusion criteria comprised all hospital admission episodes of pediatric patients (aged 0-17 years, inclusive) with a length of stay greater than 24 hours, and at least one of the following principal or secondary diagnoses according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10): A37, A15, R06.2, H66, M35.81, J00, J01, J02, J03, J04, J05, J06, J09, J10, J11, J12, J12.81, J13, J14, J15, J16, J17, J18, J20, J21, J22. The predefined exclusion criterion was the absence of electronic clinical records, which could hinder diagnosis classification.

Two strategies were employed to obtain a comprehensive list of hospitalizations meeting the inclusion criteria: 1) search in the administrative databases of the Information Department of CHUPorto; and 2) search in the clinical databases of the Pediatric Department of CHUPorto. After cross-checking all admission episodes, data were collected by the research team using electronic clinical records.

Demographic and administrative data were retrieved, including age, gender, length of hospital stay, and ICD-10 diagnosis. Additionally, data on the clinical presentation of the disease, diagnostic workup, and therapeutic interventions performed during hospitalizations were analyzed.

The ICD-10 diagnoses for each hospitalization were classified as upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) or lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs; Table 1). Influenza was considered as a separate group. Considering the first case of COVID-19 identified in Portugal, the years were divided into the following subgroups: year 1 (Y1) from April 2018 to March 2019; year 2 (Y2) from April 2019 to March 2020; and year 3 (Y3) from April 2020 to March 2021. Y3 was considered the ‘COVID-19 year’.

Table 1 Classification of respiratory tract infections based on ICD-10.

| Upper respiratory tract infections | Lower respiratory tract infections | Influenza | |||

| ICD-10 | Disease | ICD-10 | Disease | ICD-10 | Disease |

| J00 | Acute nasopharyngitis (common cold) | J12 | Viral pneumonia, not elsewhere classified | J09 | Influenza |

| J01 | Acute sinusitis | J12.81 | Pneumonia due to SARS- associated coronavirus | J10 | Influenza due to identified influenza virus |

| J02 | Acute pharyngitis | J13 | Pneumonia caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae | J11 | Influenza, virus not identified |

| J03 | Acute tonsillitis | J14 | Pneumonia caused by Haemophilus influenzae | ||

| J04 | Acute laryngitis and tracheitis | J15 | Bacterial pneumonia, not elsewhere classified | ||

| J05 | Acute obstructive laryngitis (croup) and epiglottitis | J16 | Pneumonia due to other infectious organisms, not elsewhere classified | ||

| J06 | Acute upper respiratory infections of multiple and unspecified sites | J17 | Pneumonia in diseases classified elsewhere | ||

| H66 | Suppurative and unspecified otitis media | J18 | Pneumonia, organism unspecified | ||

| J20 | Acute bronchitis | ||||

| J21 | Acute bronchiolitis | ||||

| J22 | Unspecified acute lower respiratory infection | ||||

| A15 | Respiratory tuberculosis | ||||

| A37 | Whooping cough | ||||

| R06.2 | Wheezing | ||||

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS® version 27 (SPSS IBM, New York, NY, USA). Continuous variables were described using means and standard deviations (SD) when the variable had a symmetric distribution, and using means, 25th centiles (P25), and 75th centiles (P75) when the variable had a nonsymmetric distribution. Categorical variables were described using absolute and relative frequencies and compared using Pearson’s chi-squared test. Comparison of the frequency of hospitalizations per year was performed using a one-sample proportion test. The analysis was conducted under the assumption that data were missing completely at random, i.e. there were no systematic differences between missing values and observed values. Therefore, full information was used, not just complete data. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all inferential analyses.

Results

All hospitalization episodes identified according to the inclusion criteria had adequate electronic clinical records, and no episode was excluded. Between April 2018 and March 2021, there were 783 hospitalizations of pediatric patients with a diagnosis of respiratory infection at CMIN (Table 2). Of these, 687 involved patients with only one hospitalization during the considered 3 years, while the remaining 96 episodes were repeated hospitalizations (40 patients with 2 admissions, 4 patients with 3 admissions, and 1 patient with 4 admissions). There was a significant decrease in the number of hospitalizations in Y3 (73% reduction from Y1 to Y3 and 67% reduction from Y2 to Y3; p<0.001), along with a concomitant decrease in all absolute frequencies of hospitalization diagnoses. In Y3, the median age of admission was significantly higher than in previous years (Y1: 10 months, Y2: 5 months, Y3: 20 months; p<0.001).

Table 2 Characteristics of the study population.

| 04/2018 - 03/2019 | 04/2019 - 03/2020 | 04/2020 - 03/2021 | TOTAL | |

| Total admissions | 374 (47.8) | 308 (39.3) | 101 (12.9)* | 783 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 162 (43.3) | 127 (41.2) | 46 (45.5) | 335 (42.8) |

| Male | 212 (56.7) | 181 (58.8) | 55 (54.5) | 448 (57.2) |

| Age (months) | ||||

| Median (SD) | 10 (38) | 5 (42) | 20 (69)* | 8 (46) |

| Age group, n (%) | ||||

| [0-6[ months | 148 (39.6) | 159 (51.6) | 26 (25.7) | 333 (42.5) |

| [6-12[ months | 61 (16.3) | 49 (15.6) | 15 (14.9) | 124 (15.8) |

| [12-24[ months | 61 (16.3) | 36 (11.7) | 13 (12.9) | 110 (14.0) |

| [2-6[ years | 74 (19.8) | 35 (11.4) | 22 (21.8) | 131 (16.7) |

| [6-10[ years | 7 (1.9) | 9 (2.9) | 5 (5.0) | 21 (2.7) |

| [10-18[ years | 23 (6.1) | 21 (6.8) | 20 (19.8) | 64 (8.2) |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | ||||

| Median (SD) | 5 (6) | 5 (7) | 5 (6) | 5 (7) |

| Diagnosis group, n (%) | # | |||

| URTI | 46 (12.3) | 35 (11.4) | 4 (4.0) | 85 (10.9) |

| LRTI | 313 (83.7) | 261 (84.7) | 96 (95.0) | 670 (85.6) |

| Flu | 15 (4.0) | 12 (3.9) | 1 (1.0) | 28 (3.6) |

| Specific diagnoses, n (%) | ||||

| Acute otitis media | 13 (3.5) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (1.8) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 23 (6.1) | 27 (8.8) | 3 (3.0) | 53 (6.8) |

| Pharyngitis/Tonsilitis | 7 (1.9) | 6 (1.9) | 1 (1.0) | 14 (1.8) |

| Laryngitis/Croup | 4 (1.1) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.6) |

| Bronchitis | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.5) |

| Bronchiolitis | 210 (56.1) | 185 (60.1) | 35 (34.7)* | 430 (54.9) |

| Pneumonia | 115 (30.7) | 83 (26.9) | 61 (60.4)* | 259 (33.1) |

| Whooping cough | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 4 (0.5) |

n, number; SD, standard deviation. *p<0.001 for differences between 04/2020-03/2021 and the previous years. #p=0.015 for differences in the frequency of diagnosis groups between 04/2020-03/2021 and the previous years

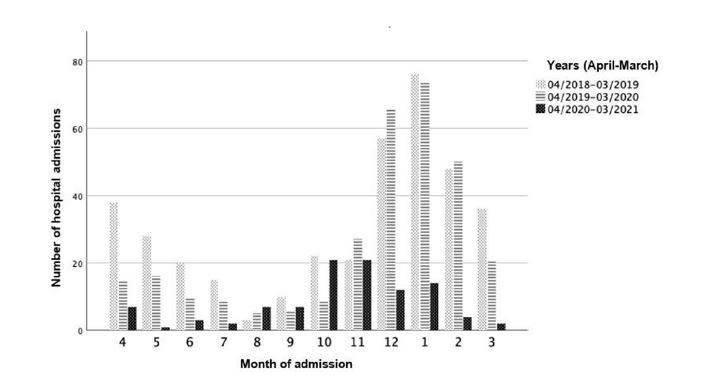

Monthly seasonality was similar in Y1 and Y2, with a higher proportion of hospitalizations for respiratory infections in the winter months (December-February) and significantly fewer hospitalizations in the summer months (July-September; Figure 1). In contrast, in Y3, the number of admissions remained constant between April and September, with a slight increase between October and January.

There was a significant decrease in the incidence of URTI and a corresponding increase in the incidence of LRTI in Y3 (p=0.015; Table 2). Within the LRTI group, there was a significant decrease in the incidence of bronchiolitis admissions and a significant increase in the incidence of pneumonia admissions in Y3 (38% decrease from Y1 to Y3; 42% decrease from Y2 to Y3; p<0.001; and 96% increase from Y1 to Y3; 124% increase from Y2 to Y3; p<0.001, respectively).

The clinical presentation was significantly different between Y1/Y2 and Y3, with a higher proportion of vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain and a lower proportion of cough, respiratory distress, and hypoxemia in Y3 (Table 3).

Table 3 Clinical characteristics of the study population and comparison between Y1/Y2 and Y3.

| 04/2018 - 03/2019 | 04/2019 - 03/2020 | 04/2020 - 03/2021 | TOTAL | |

| Days of illness before admission, median (SD) | 3 (5) | 3 (4) | 3 (5) | 3 (4) |

| Clinical presentation, n (%) | ||||

| Cough | 304 (81.3) | 256 (83.1) | 66 (65.3)* | 628 (79.8) |

| Rhinorrhea | 217 (58.0) | 227 (73.7) | 57 (56.4) | 504 (64.0) |

| Dyspnea | 155 (41.4) | 160 (51.9) | 47 (46.5) | 365 (46.4) |

| Vomiting | 55 (14.7) | 74 (24.0) | 30 (29.7)+ | 160 (20.3) |

| Diarrhea | 20 (5.3) | 18 (5.8) | 16 (15.8)* | 55 (7.0) |

| Abdominal pain | 5 (1.3) | 12 (3.9) | 8 (7.9)# | 25 (3.2) |

| Respiratory distress | 284 (75.9) | 231 (75.0) | 56 (54.5)* | 573 (72.8) |

| Fever | 241 (64.4) | 189 (61.6) | 60 (59.4) | 492 (62.6) |

| Hypoxemia | 215 (57.5) | 191 (62.0) | 48 (47.5)¥ | 458 (58.2) |

n, number; SD, standard deviation. Comparisons between Y1-2 and Y3: *p<0.001; +p=0.012; #p=0.004; ¥p=0.022

Blood workup (specifically complete blood count, biochemistry [mainly electrolytes, renal function, and inflammation markers], and blood culture) was performed in a higher proportion of hospitalizations in Y3 (p<0.001 for blood count and biochemistry; p=0.022 for blood culture; Table 4). Conversely, nasopharyngeal aspirate for viral identification was performed in a lower proportion of admissions in Y3 (55.4% in Y3 vs. 78.1% in Y1 and 86.7% in Y2; p<0.001). In addition, computed tomography (CT) scans were performed in a higher proportion of patients admitted in Y3 compared to the other years (10.9% in Y3 vs. 3.7% in Y1 and 5.6% in Y2; p<0.001).

Table 4 Workup performed and treatments administered in the study hospitalizations.

| 04/2018 | 04/2019 | 04/2020 | |||||||

| - | - | - | TOTAL | ||||||

| 03/2019 | 03/2020 | 03/2021 | |||||||

| Microbiology, n (%) | |||||||||

| Viral Nasopharyngeal | 292 (78.1) | 267 (86.7) | 56 (55.4)* | 615 (78.5) | |||||

| Blood culture | 147 (39.3) | 107 (34.7) | 52 (51.5)¥ | 306 (39.1) | |||||

| Sputum microbiology | 84 (22.5) | 68 (22.1) | 18 | (17.8) | 170 (21.7) | ||||

| SARS-CoV2 PCR | 0 | (0) | 9 | (2.9) | 100 (99.0)* | 109 (13.9) | |||

| Blood, n (%) | |||||||||

| Hemogram | 224 (59.9) | 197 (64.0) | 82 (81.2)* | 503 (64.2) | |||||

| Biochemical | 220 (58.8) | 195 (63.3) | 82 (81.2)* | 497 (63.5) | |||||

| Chest image, n (%) | |||||||||

| X-ray | 201 (53.7) | 176 (57.1) | 64 | (63.4) | 441 (56.3) | ||||

| CT scan | 14 (3.7) | 8 | (5.6) | 11 (10.9)* | 33 | (4.2) | |||

| Treatments, n (%) | |||||||||

| Supplemental O2 | 229 (61.4) | 192 (62.3) | 50 | (49.5)# | 471 (60.2) | ||||

| Inhaled β-agonists | 186 (49.7) | 140 (45.5) | 38 | (37.6) | 364 (46.5) | ||||

| Inhaled steroids | 97 (25.9) | 60 (19.5) | 25 | (24.8) | 182 (23.2) | ||||

| Systemic steroids | 119 (31.8) | 81 (26.3) | 41 | (40.6)+ | 241 (30.8) | ||||

| Antibiotics | 150 (40.1) | 120 (39.0) | 46 | (45.5) | 316 (40.4) | ||||

| Antiviral | 23 | (6.1) | 29 | (9.4) | 2 | (2.0)++ | 54 | (6.9) | |

CT, computed tomography; n, number; Comparisons between Y1-2 and Y3: *p<0.001; ¥p=0.022; #p=0.018; +p=0.023; ++p=0.037

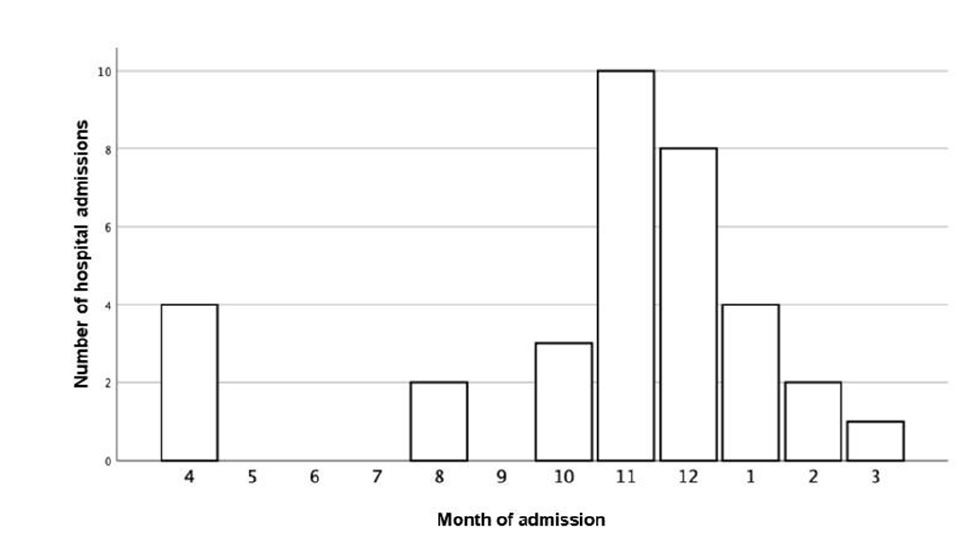

The main respiratory infection etiologies identified during the study period were viral (69.5%), specifically RSV (35.4%), followed by RV (17.1%), and influenza (6.4%; Table 5). Bacteria (in blood culture or sputum microbiology) were identified in 8.4% of cases, mainly, Haemophilus influenza (1.4%), Streptococcus pneumonia (0.9%), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (0.9%). In Y3, the proportion of identified viruses and bacteria was significantly lower (p<0.001 and p=0.013, respectively). As expected, there was a significant number of SARS-CoV-2 infections in Y3 (31.7%), with a higher incidence in November and December (Figure 2). There were two SARS-CoV-2 infections (0.6%) in Y2 (at the end of March 2020). Additionally, no admissions for SARS-CoV-2 infection were reported in May, June, July, or September 2020.

In Y3, fewer hospitalized patients were treated with supplemental oxygen (49.5% in Y3 vs. 61.4% in Y1 and 62.3% in Y2; p=0.018) or antivirals (2.0% in Y3 vs. 6.1% in Y1 and 9.4% in Y2; p=0.037; Table 4). Conversely, systemic steroids were more commonly used more in Y3 (40.6% in Y3 vs. 31.8% in Y1 and 26.3% in Y2; p=0.023).

Table 5 Viruses and bacteria identified in the study hospitalizations.

| 04/2018 - 03/2019 | 04/2019 - 03/2020 | 04/2020 - 03/2021 | TOTAL | |

| Virus, n (%) | 251 (67.1) | 236 (76.6) | 57 (56.4)* | 544 (69.5) |

| RSV | 131 (35.0) | 144 (46.8) | 2 (2.0)* | 277 (35.4) |

| Rhinovirus | 64 (17.1) | 47 (15.3) | 23 (22.8)* | 134 (17.1) |

| Influenza | 23 (6.1) | 26 (8.4) | 1 (1.0) | 50 (6.4) |

| Adenovirus | 22 (5.9) | 15 (4.9) | 5 (5.0) | 42 (5.4) |

| Enterovirus | 20 (5.3) | 19 (6.2) | 2 (2.0) | 41 (5.2) |

| Parainfluenza | 21 (5.6) | 15 (4.9) | 1 (1.0) | 37 (4.7) |

| Metapneumovirus | 18 (4.8) | 18 (5.8) | 0 (0.0) ¥ | 36 (4.6) |

| Bocavirus | 21 (5.6) | 13 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 34 (4.3) |

| Coronavirus | 10 (2.7) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (1.0) | 12 (1.5) |

| CMV | 1 (0.3) | 4 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.6) |

| EBV | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) |

| SARS-Cov2 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.6) | 32 (31.7)* | 34 (4.3) |

| Bacteria, n (%) | 39 (10.4) | 22 (7.1) | 5 (5.0)# | 66 (8.4) |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 5 (1.3) | 6 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (1.4) |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 4 (1.1) | 3 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (0.9) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 4 (1.1) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (1.0) | 7 (0.9) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (2.0) | 5 (0.6) |

| Moraxella catharralis | 2 (0.5) | 3 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.6) |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | 3 (0.8) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.5) |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 3 (0.8) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.5) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.4) |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 3 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.4) |

| Staphylococcus coagulase | 3 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.4) |

| Staphylococcus capitis | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) |

| MRSA | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 0.0) | 2 (0.3) |

| Escherichia coli | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) |

| Bordetella pertussis | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (0.3) |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) |

| Acinetobacter baumanii | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.1) |

| Bordetella parapertussis | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) |

| Serratia marcescens | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) |

| Cupriavidus | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) |

CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV: Epstein-Barr virus; n, number; MSRA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; RSV: respiratory syncytial virus. Comparisons between Y1-2 and Y3: *p<0.001; #p=0.013; ¥p=0.039

Discussion

This study showed a 73% and 67% decrease in the number of hospitalizations occurring between April 2020 and March 2021 compared to the same months in 2018-2019 and 2019-2020, respectively (Figure 1). Similar data were observed in France, China, England, Australia, and Poland.12,19-22 The study also demonstrated that there was no peak in hospital admissions for respiratory infections during the winter months of 2020-2021, in contrast to the previous two years. This finding was also reported in a UK study, where RSV was identified in only 2% of patients admitted between April 2020 and March 2021, while SARS-CoV-2 was identified in 32% of patients during the same period .23

In Portugal, all teaching activities in schools were suspended in March 2020 and the first state of emergency was declared.24,25 On May 1, the use of masks/visors became mandatory in educational institutions for all staff and students aged 6 years and older.26 These measures may have had an immediate impact, as the present study showed a sharp decrease in hospitalizations between April and July 2020 compared to the same months in 2018 and 2019. Therefore, there was an immediate positive impact of NPIs on SARS-CoV-2 transmission, which is consistent with data in the literature.11,27

In September 2020, schools resumed, and this was likely the cause of the similar number of hospitalizations observed between September and November in the three years of this study. Additionally, there was an increase in the number of SARS-CoV-2 infections in October and November 2020.28 This is supported by this study’s data, as November 2020 was the month with the highest number of SARS-CoV-2-positive hospitalizations (Figure 2).

On January 21, 2021, the government again declared schools and daycare centers closed.29 Data from December 2020 to March 2021 showed a marked decrease in hospitalizations compared to the same period in previous years. As a result, there was no peak in respiratory infection hospitalizations typically seen in the winter months. Thus, the SARS-CoV-2 NPIs appear to have also reduced the transmissibility of other respiratory viruses, as observed in New Zealand.30

Regarding diagnostic groups, the increase in the incidence of pneumonia in Y3 can be explained by SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. As for bronchiolitis, several studies have shown an abrupt decrease following the implementation of SARS-CoV-2 NPIs.12,17 It has even been suggested that these types of infections do not become epidemics when non-pharmacological measures inhibit their transmission.31

This study showed a significant increase in the median age of patients admitted in Y3, similar to findings from another study, where hospitalizations increased, particularly among children between six and ten years old.16 As bronchiolitis is the leading cause of hospitalization in the first 12 months of life in developed countries, the observed decrease in these infections resulted in a proportional shift towards older hospitalized patients.32

Regarding symptoms, there was a significant increase in the frequency of vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain in this study. This may be attributed to the incidence of SARS- CoV-2 infection, as nearly a quarter of patients have been shown to present with gastrointestinal symptoms.33 Conversely, there was a significant decrease in the number of patients hospitalized with respiratory distress and hypoxemia, possibly due to a change in hospitalization criteria, as patients with less severe respiratory symptoms but with SARS-CoV-2 infection were admitted due to lack of knowledge about the course of the disease.

There was a significant decrease in viral identification in the present study (Table 5). Specifically, there was a significant decrease in RSV (2% in Y3 vs. 35% and 46.8% in Y1 and Y2, respectively). In contrast to these findings, the seasonality of RSV in China did not change in 2020.19

Interestingly, RSV was identified in 22.8% of hospitalizations between April 2020 and March 2021, an increased proportion compared with the previous two years. This was also observed in the UK and China, where it even became the most common respiratory virus across all age groups in 2020.19,23 In an Austrian study, rhino-/enterovirus infections in children up to 24 months occurred throughout the winter, independent of NPIs.34 As RSV is a major cause of asthma exacerbations in children, the increase in hospitalizations can be explained by more RSV infections in these children, coupled with fewer hospitalizations due to other viruses.35

There was a significant reduction in the use of oxygen therapy, consistent with the observed reduction in hypoxia. Additionally, there was a reduction in antiviral treatments, likely related to the decrease in hospitalizations due to influenza viruses. This study also showed a significant increase in the use of systemic steroids, which were administered to more severely hospitalized COVID-19 patients.36

The main strength of this study was the comprehensive clinical analysis of all hospitalized pediatric patients with respiratory diseases in one of the main tertiary referral hospitals in Portugal. However, the study also has limitations. It was a retrospective study, thus relying on adequate ICD-10 coding and clinical records. Two different strategies were used to mitigate missed codings. Patients with both primary and secondary diagnoses of respiratory infections were included, but it was not possible to analyze the specific differences between primary and secondary diagnoses and their implications for clinical presentation, length of stay, and treatment. Another study limitation was the lack of analysis of the subgroup of children hospitalized with chronic diseases, who may have had longer hospital stays, different bacterial isolates, and different treatments.

In the future, studies assessing the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of NPIs in different respiratory diseases and settings are essential. These studies have the potential to inform policy and public health decisions to implement durable interventions that can reduce not only the clinical burden of hospitalization for respiratory infections in children, but also the economic burden on national health systems and society as a whole.

Conclusions

This study showed a significant reduction in hospitalizations for respiratory tract infections following the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 and the implementation of measures to reduce airborne transmission. The study also showed that there was no peak in hospital admissions for respiratory infections during the winter months of 2020-2021, unlike the previous two years. A dramatic reduction in respiratory infections caused by the other respiratory viruses, especially RSV, was observed. This allowed to conclude that the NPIs implemented to reduce the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic were also effective in reducing the transmission of other viruses, with a direct impact on the reduction of pediatric hospitalizations for respiratory infections.

Authorship

Sara Monteiro - Formal Analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Data Curation; Visualization; Writing - original draft

Luís Salazar - Investigation; Data Curation; Visualization; Validation; Writing - review & editing

João Oliveira - Investigation; Data Curation; Visualization; Validation; Writing - review & editing

Mariana Souto - Investigation; Data Curation; Visualization; Validation; Writing - review & editing

Lurdes Morais - Investigation; Data Curation; Visualization; Validation; Writing - review & editing

Ana Ramos - Investigation; Data Curation; Visualization; Validation; Writing - review & editing

Manuel Ferreira-Magalhães - Conceptualization; Methodology; Data Curation; Investigation; Formal analysis; Supervision; Visualization; Validation; Writing - review & editing