Introduction

New adhesives called universal or multimode adhesives have been recently developed. These adhesives are more versatile and, theoretically, can be used with or without acid etching in both dentin and enamel.1,2

Universal adhesives applied on dentin have been shown to have high bond strength values using both the self‑etch (SE) and etch‑and‑rinse (ER) techniques. This feature may be due to the presence of special amphiphilic monomers, such as methacryloyloxydecyl dihydrogen phosphate (MDP) or glycerol phosphate dimethacrylate (GPDM), that promote chemical bonding to the tooth.3,4,5Some studies have shown that both the SE and ER techniques achieve comparable bond strength values on dentin.3,5On enamel, the bond strengths of non‑universal adhesives are always higher with the ER mode compared to the SE mode.6,7

Laboratory and clinical results do not always show a direct correlation. Whether in vitro results also occur in vivo is yet to be confirmed. Moreover, clinical trials investigating the effectiveness of universal adhesives are limited, despite the importance of evaluating their clinical performance.8,9In general, non‑carious cervical lesions (NCCLs) are considered ideal for determining adhesives’ clinical effectiveness because they provide minimal, if any, macro‑retention; thus, all retention relies solely on the adhesion effectiveness of the adhesives tested and an ineffective bonding results in restoration loss.10

Furthermore, in these lesions, the restoration is bonded to both enamel and dentin, access is simple and does not require complicate restorative techniques, and restoration is also possible with a low C‑factor.10,11

Some clinical studies8,9,12conducted with universal adhesives on NCCLs reported no differences in the universal adhesive behavior when applied using the SE or the ER technique.

Other studies have demonstrated the superiority of the ER technique compared to the SE technique.1,13This randomized, double‑blind clinical study aimed to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of a universal adhesive applied with two different application strategies SE and ER on NCCLs.

The null hypothesis was that there was no difference in clinical performance between the ER and SE application modes.

Material and methods

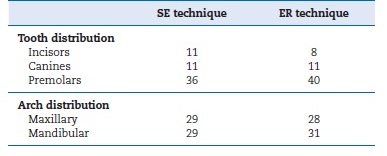

This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement.14 The study was a double‑blind, randomized clinical trial that took place in the clinic of the Faculty of Dental Medicine of the University of Lisbon. All participants were informed about the study’s nature and objectives, but were not aware of what lesion received the treatments under evaluation. The Local Ethics Committee reviewed and approved the protocol and the consent form for this study. Based on pre‑established criteria, 26 participants, 15 females and 11 males, with NCCLs in incisors, canines, and premolars (Table 1) were selected. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before treatment.

As inclusion criteria, participants had to be at least 18 years old and in good general health. They needed to have at least 20 teeth in occlusion and an acceptable oral hygiene level.

Their lesions had to be nonretentive, non‑carious, and deeper than 1 mm. The lesions had to involve both the enamel and dentin of vital teeth without mobility. The cavosurface margin could not involve more than 50% of the enamel.15

Every tooth included in the study was in occlusion and proximal contact with the adjacent tooth. All patients were given oral hygiene instructions before operative treatment.

Patients with heavy bruxism habits, xerostomia, poor oral hygiene, severe or chronic periodontitis, or smoking habits were excluded from the study.8,9

The same operator restored all lesions. The operator was not blinded to group assignment when administering interventions, but the participants were. Each patient received at least two cervical restorations: one with the ER technique and the other with the SE technique.

Before isolation with the rubber dam, the operator anesthetized the teeth with lidocaine 2% with epinephrine 1:80,000 (XilonibsaR 2%; Inibsa, Barcelona, Spain). All teeth were then cleaned with pumice and water using a rubber prophylactic cup to remove the salivary pellicle and dental plaque. They were then rinsed with water and dried. The operator did not prepare any additional retention or bevel, following the American Dental Association (ADA) guidelines.16

The teeth were randomly assigned, using randomization tables, for restoration with either of two application procedures: Adhese Universal (ADH, Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein) in the ER mode (ADH‑ ER) or Adhese Universal in the SE mode (ADH‑SE). A total of 117 cervical lesions were restored: 59 with ADH‑ER and 58 with ADH‑SE. Only a maximum of three restorations per group was placed in one patient so that, per patient, restorations prepared following the two different protocols were mutually compared.

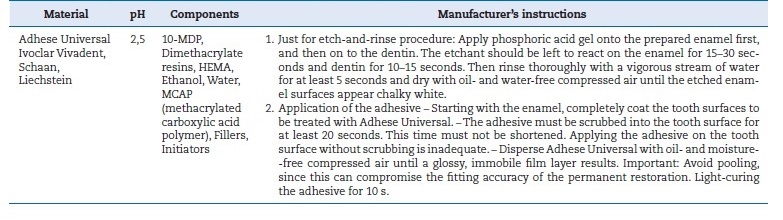

The adhesive Adhese Universal (ADH) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Table 2). The resin composite (Tetric EvoCeram, Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein) was applied in increments of up to 2 mm, each one light‑cured for 40 seconds under an LED light‑curing unit (Elipar S10; 3M ESPE, Seefeld, Germany) with a light intensity of 600 mW/cm2 (6 J/cm2). The curing light’s output was periodically verified at >600 mW/cm2 with a radiometer (Curing Radiometer P/N 10503, Kerr, Orange, CA, USA) throughout the study. The restorations were finished immediately with fine‑grain diamond burs (Diatech Dental AG, Heerbrugg, Switzerland). Polishing was performed with rubber points (Astropol, Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein).

Table 2 Components, composition (information supplied by the manufacturer), and application mode of the tested adhesive.

Two calibrated independent experienced dentists evaluated the restorations with the aid of a 2.5x‑magnification dental loupe at baseline and after 6 months. They were unaware of which material had been used; thus, the study was double‑blind.

Each restoration was documented by photographs. The examiners were calibrated before the baseline evaluation, evaluating 15 restorations representing each score for each criterion, from 15 different patients with cervical restorations that did not participate in this study. Each examiner evaluated each restoration on two different time points, on two consecutive days. Cohen’s kappa statistic was used to analyze the interexaminer agreement. An intraexaminer and interexaminer agreement of at least 85% was required for the evaluation to begin.17

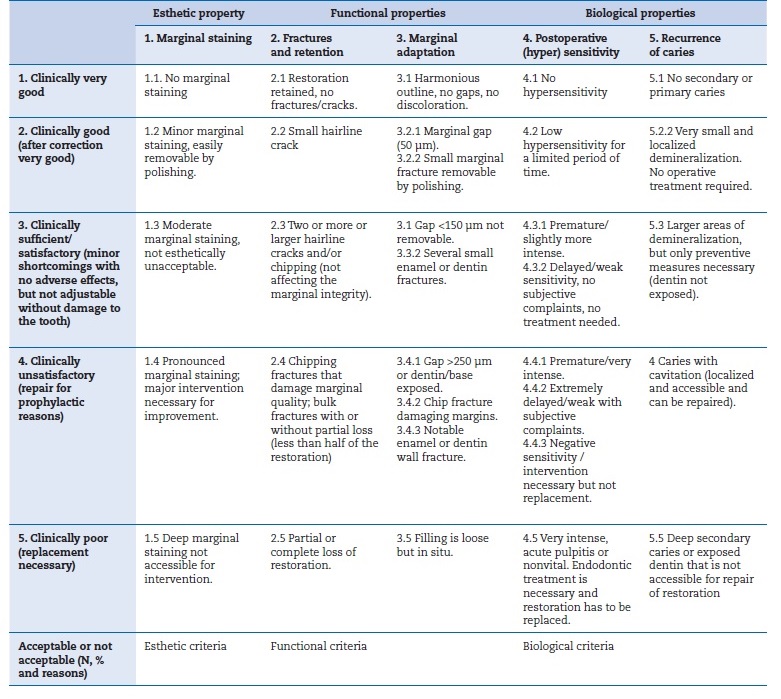

The restorations were evaluated under the World Dental Federation (FDI) criteria (Table 3).18,19Both examiners evaluated all the restorations once and independently; any discrepancy between evaluators was resolved chairside.

Sample size calculations were performed using the G*Power Program Statistical Analysis (G*Power Program, Dusseldorf, Germany) with an α=0.05, a power of 80%, and a two‑sided test.20,21The minimal sample size was 50 restorations per group in order to detect a difference of 20% among the tested groups.

The results were analyzed statistically by a paired chi‑square test - McNemar test (SAS Institute Inc., SAS/STAT 9.3 User’s Guide, Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc., 2002‑2010) - with an α=0.05, to compare differences between baseline and 6 months. A generalized estimating equation modeling analysis was also used to compare the two techniques while controlling potential clustering problems due to multiple teeth from the same patient.

Results

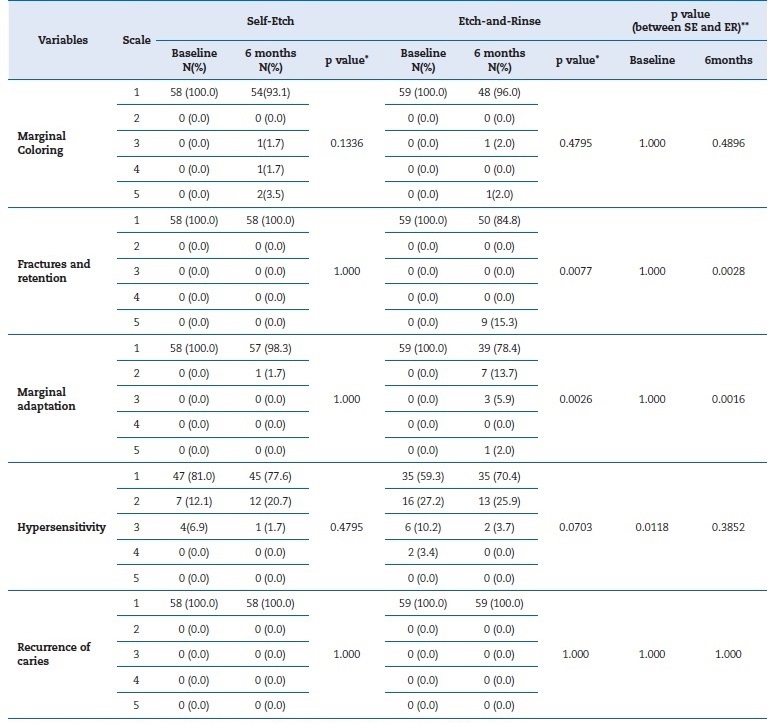

Results from the restorations’ evaluation are presented in Table 4, summarized as frequencies and proportions. Strong agreement between the examiners was found, with a kappa value of 0.87. Recall rates were at 100% for all follow‑ups.

Table 4 Number of evaluated restorations for each experimental group classified according to the World Dental Federation (FDI) criteria

* From McNemar test, and categories 2‑5 were combined for the test; ** From GEE model analysis.

In the ADH‑SE group, no differences were found in the performance of restorations between baseline and the 6‑month follow‑up (marginal coloring: p=0.1366; fractures/retention: p=1.000; marginal adaptation: p=1.000; hypersensitivity: p=0.4795; recurrence of caries: p=1.000). However, in the ADH‑ER group, significant differences (p<0.01) were found regarding both fractures/retention (p=0.0028) and marginal adaptation (p=0.0016).

At baseline, significant differences were found between the two techniques on hypersensitivity (p=0.0118) (proportion of no hypersensitivity: 81% in the ADH‑SE vs. 59% in the ADH‑ER group). However, at 6 months, no differences were observed in postoperative sensitivity between these techniques (p=0.3852).

At 6 months, significant differences were detected between groups regarding fractures/retention and marginal adaptation (p<0.01). The ER technique had a lower proportion of FDI criteria’ level 1 than the SE technique (84.8% vs. 100% for fractures/retention and 78.4% vs. 98.3% for marginal adaptation). Nine restorations were lost at 6 months in the ADH‑ER group according to the FDI criteria. No restorations were lost due to caries.

There were no dropouts in this study, so all patients were evaluated at baseline and at 6 months. Representative images of restorations are presented in Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6.

Figure 2 Photographs after 6 months of tooth 34’s restoration by the etch‑and‑rinse technique and tooth 45’s restoration by the self‑etch technique

Figure 4 Photographs after 6 months of tooth 44’s restoration by the self‑etch technique and tooth 45’s restoration by the etch‑and‑rinse technique

Discussion

The clinical success of resin composite restorations depends on effective adhesion to enamel and dentin. Clinical studies are the first level of scientific evidence to evaluate the effectiveness of dental adhesives.22

Since universal adhesives have only recently been introduced, most studies found in the literature are laboratory tests, mainly microtensile bond strength tests. The results from these in vitro studies on dentin are very similar between the ER and SE techniques.3,8,23For enamel, it seems that etching the enamel prior to universal adhesive application improves bond strength because etching creates microporosities that are readily penetrated by the adhesive.24,25,26,27,28,29

Although in vitro studies can help us understand the behavior of adhesives,30,31clinical trials with controlled and standardized study designs are the ultimate test to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of universal adhesives, preferably in NCCLs.32

This study was designed following the recommendations of the ADA. These indicate that each group should have at least 30 restorations, with a minimum of 25 patients in the initial phase of the study and 20 patients after six months, as well as a gender and age balance between study groups. In this study, a universal adhesive’s clinical performance was evaluated at baseline and after 6 months. One hundred seventeen NCCLs were restored in 26 patients, with the adhesive applied in SE and ER modes, combined with a resin composite. Each patient received at least two cervical restorations to ensure that they had a restoration from each technique, to control various environmental factors (such as oral hygiene, saliva composition, and diet).33

Due to the expulsive configuration of the NCCLs, the retention of restorations depends on a strong and stable bond of restorative material to dentin. The occurrence of structural changes in enamel and dentin resulting from age, such as dentin sclerosis, may negatively impact the quality of that bond and, consequently, the retention and longevity of cervical restorations.34This is of special concern with NCCLs where dentin is often sclerotic and, thus, more mineralized than normal dentin.35,36In fact, Mjor27 attributed the rather poor success scored with adhesives in clinical trials (in contrast to laboratory results) to the extreme variety of dentin composition and structure found clinically.37,38

Reactive sclerosis occurs in response to slowly progressive or mild irritations like mechanical or chemical erosion and abrasion in response to severe insults, like aggressive operative procedures, attrition, and caries.37,39 Several studies show that dentin sclerosis increases with age,37,39,40which may explain why greater restoration losses have been found in older patients: patients aged 21‑40, 41‑60, and 61‑ 80 years had restoration losses of 31%, 62%, and 75%, respectively.41However, other studies have shown that retention failures cannot be associated with substrate type only,34confirming that the process of adhesion involves multifactorial aspects. Indeed, a clinical study (2000)42had an equal number of restoration failures in sclerotic and non‑sclerotic lesions, indicating that the negative interaction between dentin sclerosis and the clinical retention of adhesive systems is yet to be confirmed. In this study, there was no relationship between age and restoration loss.

A period of 6 months to 1 year seems to be sufficient to predict an adhesive’s clinical behavior accurately.43 In fact, in this study, the 6‑month evaluation period was sufficient to detect significant differences in the performance of the tested adhesive system, which belongs to a novel family of universal adhesives for which there are insufficient clinical studies.

In this study, after 6 months, nine restorations failed as a result of debonding, which highlights the poor bonding efficacy of ADH when used with the ER strategy. Furthermore, at 6 months, the ER technique had poorer results than the SE technique for marginal adaptation (78.4% vs. 98.3%). The good performance of the SE restorations is likely due to the presence of an acidic functional monomer, 10‑MDP, because calcium ions (released upon the partial dissolution of hydroxyapatite) diffuse within the hybrid layer and assemble the MDP molecules into nanolayers.44This chemical interaction between hydroxyapatite and MDP creates a stable nanolayer, which can form a stronger area at the adhesive interface to both enamel and dentin, as both contain hydroxyapatite.45,46,47Results obtained with the ER technique can be explained by the incomplete infiltration of the deeply demineralized collagen network by the bonding resin, which occurs because the phosphoric acid can decalcify dentin more deeply than the adhesive can infiltrate.48,49 Due to this incomplete impregnation of the demineralized substrate, the adhesive interface is not impermeable, and, as a result, water and dentinal fluid can easily move through the adhesive interface with consequent nanoinfiltration.50,51,52

Marginal discoloration was observed with both techniques, but no statistically significant differences were found. In the ADH‑ER group, one restoration exhibited deep marginal staining and another presented moderate marginal staining; these were not esthetically unacceptable. Discolorations were observed in the gingival margins, where cementum or dentin are more likely found than enamel margins.53In the SE technique, two restorations showed deep marginal staining, one restoration exhibited pronounced marginal staining, and one restoration presented moderate marginal staining; these were not esthetically unacceptable. The discoloration was located at the enamel margin, which may suggest the importance of including enamel’s selective conditioning with phosphoric acid to obtain the best marginal seal of restorations.54ADH is considered a mild SE adhesive, as other available universal adhesives, because it presents a pH of 2.5. Due to their moderately high pH, these adhesives have limited interaction with enamel as they cannot condition enamel as effectively as in the ER technique, resulting in increased marginal changes.45In fact, some studies concluded that additional etching of the enamel cavity margins resulted in an improved marginal adaptation on the enamel side. However, this was not critical and did not affect the overall clinical success of restorations.55,56

Marginal discoloration may be a clinical sign of future restoration failure, but it does not imply the imminent need for replacement because these discolorations, if superficial, can be removed by polishing and routine finishing.10,57,58

In this study, no restoration had secondary caries, maybe because the participants selected for this study had good oral hygiene habits.57

In this study, there was a significant difference in postoperative sensitivity between the SE and ER techniques at baseline.

Postoperative sensitivity was higher with the ER technique, possibly because phosphoric acid removes the peritubular dentin and fully opens the dentin tubules,59 which the adhesive may not be able to seal completely afterward. In contrast, with the SE technique, the dentin surface is smear‑layer sealed, and there is a lesser tubule opening.60Nevertheless, there was no difference in postoperative sensitivity between the ER and SE modes, which may be explained by thepulp’s capacity to recover in cases of reversible pulpitis.61 Results from the literature indicate that a decrease or absence of hypersensitivity may occur over time in those with NCCL restorations.57,62,63

Regarding the effect of clinical co‑variables (degree of sclerosis, patient age, tooth type, and gender), no correlation was found between these co‑variables and the results presented in the two groups at the 6‑month evaluation.

For this study, FDI criteria were used as opposed to the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) modified criteria because authors of recent publications comparing the 6‑month clinical performance of adhesion strategies using FDI and USPHS‑modified criteria concluded that the FDI criteria are more sensitive than the USPHS‑

modified criteria to small variations in clinical outcomes.1,8,9,64

Although significant differences were found in this study with the 6‑month evaluation, it may be interesting to consider a longer follow‑up in future investigations. It would also be important to evaluate this adhesive system’s behavior with the selective‑etch technique, comparing it with the SE and ER techniques, to better evaluate its clinical performance.