Introduction

Oral potentially malignant disorders (OPMDs) are clinical manifestations defined as benign changes with areas of modified epithelium that present a high risk of transformation into oral cancer.1 According to the literature, leukoplakia is the most common OPMD, with an estimated worldwide prevalence of 4.3% and an annual rate of malignant transformation of around 1.56%.2,3

Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia, a distinct condition, has a high risk of malignancy, with a rate of 9.3% per year, followed by erythroplakia, with a prevalence between 0.01% and 0.83% and an annual malignant transformation rate of 2.7%.2,3 Clinical entities such as oral lichen planus, oral lichenoid lesions, and oral submucous fibrosis have an anual malignant transformation rate of 0.28%, 0.57%, and 0.98%, respectively. 3 In turn, there is no consensus on the malignant transformation rate of actinic cheilitis, with values such as 3.07% and 14%.4,5

Patients with OPMD may present significant health-related symptoms, such as pain, burning sensation, functional limitations, and psychosocial impairment, due to anxiety and the burden of a chronic disease with the potential for malignancy.6,7 Recent studies indicate that these symptoms may negatively impact the oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) of individuals affected by such disorders.7-10 Furthermore, research using psychological questionnaires in these patients found increased stress, anxiety, and depression levels when compared to the control group.11,12 However, despite the rise in new cases of patients with OPMD in recent decades, the literature is scarce regarding the impact of oral problems on quality of life, anxiety, and depression in these individuals.13

OHRQoL assessment is based on the effect of oral conditions on patients’ daily activities, well-being, and quality of life.

Therefore, analyzing such outcomes allows the clinician to identify functional limitations, psychosocial aspects, and responsiveness to the management of oral symptoms and, thus, adapt treatment strategies aimed at comprehensive care and improving patients’ OHRQoL.14

Owing to the lack of specific questionnaires for assessing the OHRQoL of individuals with OPMD adapted to diferente sociocultural contexts,15 studies have used nonspecific questionnaires such as the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) and the Oral Health Impact Profile Short Form (OHIP-14) as data collection instruments. Nevertheless, most of these studies have focused on assessing quality of life only in patients with oral lichen planus.16-19

Given the social, epidemiological, and clinical relevance of the topic, the present study aimed to assess the OHRQoL and possible correlated anxiety and depression in patients with oral potentially malignant disorders.

Material and methods

This cross-sectional study was carried out from February 1, 2022, to January 31, 2023, at the Oral Injury Reference Center of the State University of Feira de Santana. It was part of a larger project and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the State University of Feira de Santana, with CAAE: 46614221.3.0000.0053.

The present study is part of a larger methodological study based on the exploratory factor analysis of 20 patients for each item analyzed.20 Thus, this study’s population was obtained using the non-probabilistic, consecutive serial sampling technique.

The inclusion criteria for this research were patients aged 18 years or older who had received a clinical diagnosis of OPMD by two examiners specialized in stomatology, with or without a histopathological diagnosis of mild, moderate, or severe epithelial dysplasia, and who, after reading the informed consent, agreed to participate in the research. On the other hand, we excluded patients with a clinical diagnosis of OPMD and a histopathological diagnosis of carcinoma in situ and patients with decompensated metabolic syndromes (diabetes mellitus, systemic arterial hypertension, autoimmune diseases, and any other disease).

The Oral Health Impact Profile-14 (OHIP-14), the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) questionnaires were used to collect data, in their respective versions validated for Brazilian Portuguese.21-23

The OHIP-14 was applied to assess individuals’ perception of the impact of oral dysfunctions on their quality of life, measuring how these dysfunctions affected their physical, psychological, and social well-being. This instrument is a reduced version of the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP) composed of 14 items grouped into 7 dimensions: functional limitation, physical pain, psychological discomfort, physical disability, psychological disability, social disability, and disability in performing daily activities.24 Patients responded to each alternative of the OHIP-14 according to the frequency of the events as “never”, “rarely”, “sometimes”, “repeatedly”, and “always”, structured on a Likert scale from 0 to 4, respectively. OHIP-14 was measured using the additive method, with the total score ranging from 0 to 56 and higher scores indicating a worse OHRQoL.25

The GAD-7 instrument aims to screen for generalized anxiety. It consists of seven items structured on a four-point scale where 0 corresponds to “never,” 1 to “several days,” 2 to “more than half the days,” and 3 to “almost every day.” The total score can range from 0 to 21 points. The items assess the following aspects: feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge; being able to stop or control worrying; worrying too much about diferente things; difficulty relaxing; being restless; becoming easily upset or irritable; feeling afraid as if something terrible could happen.26 In screening for anxiety disorders, a score of 8 represents a reasonable cutoff point to identify probable cases of generalized anxiety disorder. In this case, further diagnostic evaluation is necessary to determine the presence and type of anxiety disorder.27,28

The PHQ-9 assesses the presence of depressive symptoms in the last two weeks before the questionnaire application. The symptoms assessed consist of anhedonia; feeling depressed or without hope; sleep problems; tiredness or lack of energy; change in appetite; feelings of guilt or worthlessness; difficulty concentrating; feeling slow or restless; suicidal thoughts.29

The nine items are assessed on a four-point scale where 0 corresponds to “never,” 1 to “several days,” 2 to “more than half the days,” and 3 to “almost every day,” resulting in a total score that can range from 0 to 27 points. For this instrument, based on the sum of the items, a cutoff point ≥ 10 presents better screening performance in detecting major depressive disorder.30

Patients’ general information and clinical status were collected using a sociodemographic and clinical data assessment form containing the participant’s data; clinical data of the acute disease, including clinical diagnosis, histopathological characteristics, whether there were symptoms and treatment for the OPMD; and previous clinical data regarding lifestyle habits and oral hygiene.

Patients who were followed at the Oral Injury Reference Center for OPMD were screened regarding the inclusion and exclusion criteria by evaluating their clinical records. Then, patients who agreed to participate in the research signed the informed consent form.

The instruments were applied through interviews, in which participants verbally answered the alternatives in each questionnaire. The interviewers were previously trained to obtain the data. The information collected was recorded in a database generated on the REDCap platform.31

Because this research was developed during the COVID-19 pandemic, the prevailing biosafety measures recommended by the World Health Organization and the Ministry of Health were followed.

A descriptive analysis was performed to characterize the sample for statistical analysis. Categorical variables were described using absolute and relative frequencies, while numerical variables were presented as mean and standard deviation.

The relationship between the variables quality of life, depression, and anxiety was established using Pearson’s correlation coefficient with a 95% confidence interval. The qualitative assessment of the degree of correlation between the variables was based on the Callegari-Jacques classification.32 All analyses were performed using the statistical software GraphPad Prism version 9.0.3 (GraphPad Software, San Diego - CA, USA), and the significance level adopted was p<0.05.

Results

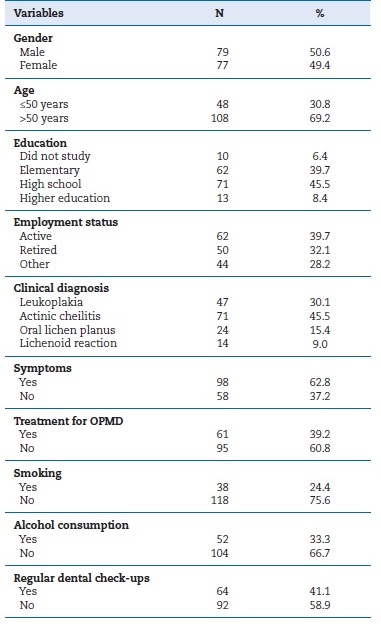

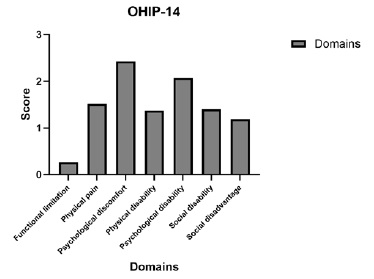

A total of 157 patients were interviewed, but one participant was excluded for not presenting all four instruments completed. The final sample had 156 patients, with a mean age of 55.3 (±14.17) years, ranging from 19 to 87 years. Table 1 describes the other sociodemographic and clinical data of the participants. The OHIP-14 presented a mean score of 10.24 (±10.10), which can be classified as a slight change in the OHRQoL in patients with OPMD. The OHIP-14 items were grouped into their respective domains and prioritized according to their impact on the patients’ quality of life, as shown in Figure 1. There was a predominance of psychological discomfort-“feeling uncomfortable” and “feeling stressed,” followed by psychological disability-“difficulty relaxing” and “feeling embarrassed,” and physical pain-“discomfort when eating” and “severe pain in the mouth.”

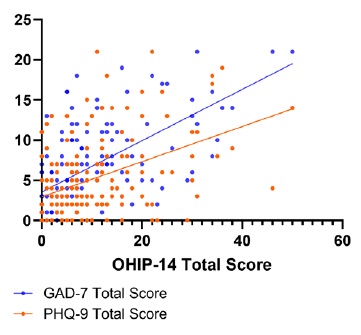

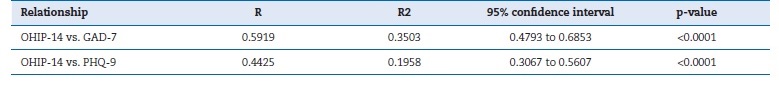

Regarding GAD-7 and PHQ-9, their mean and standard deviation scores were 6.83 (±5.43) and 5.20 (±4.97), respectively. Based on the cutoff points adopted for each instrument, approximately 39.7% (n=62) of the interviewees were probable cases of generalized anxiety, and 17.9% (n=28) had depressive symptoms. Figure 2 shows the relationship between the total scores of OHIP-14, GAD-7, and PHQ-9, analyzed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient, in which a 95% confidence interval was adopted. A moderate positive correlation was identified between OHIP-14 and GAD-7 (R=0.5919) and between OHIP-14 and PHQ-9 (R=0.4425), with a p<0.0001 for both relationships (Table 2).

Discussion

Understanding the sociodemographic and clinical profile of patients with OPMD in a given population is of the utmost importance for identifying associated risk factors, planning prevention strategies, and obtaining an early diagnosis.33 In the present study, there was a prevalence of males, with a mean age of 55.3 years, and more than half of the sample was over 50 years old; these findings are similar to those found in previous studies with Brazilian populations.34-37

Regarding clinical diagnosis, the prevalence of actinic cheilitis stands out, representing 45.5% of the sample. Araújo et al.34 state that this OPMD appears to be frequent in northeastern Brazil. Thus, the high prevalence found in the present study may derive from the location of the Reference Center in the interior of Bahia, a region under high levels of ultraviolet radiation.38

Given the impact of oral problems on the patient’s general health and well-being, assessing OHRQoL has become useful for identifying at-risk populations and is essential for developing interventions aimed at comprehensive care.39 Thus, this study aimed to evaluate the OHRQoL and possible correlated anxiety and depressive states in patients with OPMD, using the OHIP-14, GAD-7, and PHQ-9 questionnaires.

The results demonstrated a low impact of OPMD on the OHRQoL of this sample’s patients, given the average score of 10.24 on a scale of 0 to 56. However, this finding differs from a study conducted in Spain using the same collection instrument to assess the perception of OHRQoL in patients with oral lichen planus. Those authors identified a worse quality of life in patients with OPMD, with an average score of 28.01. When comparing the clinical form of oral lichen planus lesions, they found a worse quality of life associated with the group with ulcerative lesions than those with reticular presentation, with an average value of 28.84.17 In fact, evidence suggests that patients with erosive oral lichen planus present greater changes in OHRQoL, given the painful symptoms associated with its more severe clinical presentation that cause discomfort during meals and difficulty speaking, swallowing, and maintaining oral hygiene care.18,19

The prevalence of actinic cheilitis in the present study suggests that this disorder may be associated with discrete changes in the patient’s OHRQoL. The clinical presentation of this OPMD may explain this finding, since its initial characteristics include smooth, pale areas with dryness and fissures in the vermilion region of the lower lip. Given the slow development of the lesion,2 the clinical changes are often not valued by the patient and, due to their anatomical location, are not directly associated with a commitment to oral health. Longitudinal studies are required to validate this association.

The percentage of individuals diagnosed with leukoplakia in this study may have also contributed to the discrete OHRQoL changes, since the clinical presentation of this disorder initially consists of a white or grayish plaque, usually flat, which may blend with the normal mucosa.2 There are no reports of associated painful symptoms in most cases.37 The presence of the lesion is usually imperceptible to the patient.

When evaluating the OHIP-14 domains, the results of this sample indicated a prevalence of psychological discomfort, followed by psychological disability and physical pain. These findings agree with the studies by Liu et al.40 and Vilar-Villanueva et al..17 The presence of symptoms associated with the OPMD in some of the patients interviewed appeared to be related to their response to the psychological discomfort, psychological disability, and physical pain domains. In the presente study, no direct association was made between OPMD and its symptoms and the prevalence of these domains. However, a study carried out on the impact of stomatological diseases on OHRQoL demonstrated that patients with symptoms related to the sensation of dry mouth, pain or burning in the mouth or tongue, and the presence of ulcers presented a worse OHRQoL in terms of psychological discomfort, physical pain, and functional limitations.41

Among questionnaires aimed at measuring OHRQoL, the OHIP-14 is an instrument validated for the Brazilian contexto used in clinical research.21,42 However, given the diferences found, the results of this study reinforce the need for a specific quality of life questionnaire for patients with OPMDs adapted to different contexts,8 such as Brazil.15

Furthermore, due to OHIP-14’s subjective nature, Alvarenga et al.43 suggested that factors such as the patient’s personality profile and sociodemographic aspects, like housing situation, marital status, and education level, could interfere with the perception of oral health status and, consequently, with the results of studies using this model. In this sense, given the discrete OHRQoL changes in the patients in this sample, future studies should compare OHRQoL questionnaires with the clinical condition and sociodemographic variables in patients with OPMD.

According to the literature, patients with erosive oral lichen planus suffer anxiety and depression, which negatively impact their quality of life.16 Rana et al.,44 when comparing the quality of life among patients with OPMD, oral cancer, and cancer recurrence, observed that although patients with OPMD reported less impact on their quality of life, they reported higher rates concerning mood and anxiety due to the possibility of changes in the mucosa.

When analyzing the presence of psychological disorders, this study’s results showed that 39.7% and 17.9% of the sample may present generalized anxiety and depressive symptoms, respectively. These findings corroborate a qualitative study conducted in India, in which patients with OPMD reported feelings of frustration and depression because of their oral condition and the impairment of their psychological well-being.8

Vilar-Villanueva et al.17 identified that patients with oral lichen planus had higher scores compatible with anxiety and depression than the control group. Unlike the present study, they found a higher percentage of patients with depressive symptoms (64.6%) than with anxiety (35.4%).17

Psychosocial impairment in individuals with OPMD may be mainly associated with the possibility of malignant transformation and how coping with the disease may interfere with daily activities, well-being, and social interaction. Furthermore, the presence of painful symptoms concomitante with the diagnosis in younger patients seems to contribute to more anxiety symptoms than in older individuals.45

However, the present study identified a higher percentage of probable cases of anxiety in a sample mostly composed of middle-aged individuals. The identification of possible cases of anxiety and depression in this population is essential when considering the patient’s perspectives during decision-making.8 Recognizing the presence and severity of psychological distress associated with managing chronic diseases and appropriately treating it contribute to a marked improvement in quality of life.46 Suggesting associated psychological treatment can also be beneficial in monitoring patients with OPMD.16,17,47 Given the possible cases of anxiety and depression in this sample, we sought to check for a relationship between psychoemotional disorders and OHRQoL perception in these individuals.

The results demonstrated a statistically significant moderate positive correlation between the total scores of OHIP-14, GAD-7, and PHQ-9. A similar finding was reported by Yang et al.,48 who related the OHIP-14 with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in patients with oral lichen planus, and observed that OHRQoL was positively correlated with anxiety (r = 0.449; p = 0.000) and depression (r = 0.500; p = 0.000). On the other hand, Vilar-Villanueva et al.17 identified no statistical significance between HADS and OHIP-14. Nonetheless, they found that the presence of psychological disorders was associated with higher scores in psychological discomfort, psychological disability, and physical pain domains of the OHIP-14.17 Assessing OHRQoL can be challenging due to its latent concept.

However, understanding such aspects allows health professionals and services to view the patient as an individual inserted into unique life contexts with different perceptions of health. Thus, they can develop personalized treatment plans that are not exclusively curative but also promote health.42

Similar to the limitations found by Ashshi et al.,49 the cross-sectional design of the present study does not allow determining the causality of the discrete changes in OHRQoL and the presence of anxiety and depression in these patients. Furthermore, the sample size may have been affected by the pandemic period,49 when part of the population felt apprehensive about attending dental services due to the possibility of contamination with COVID-19.

Moreover, these results only represent the condition of individuals treated at a single dental service and cannot be generalized to all patients with OPMD in Brazil and other sociocultural contexts. Nevertheless, the present study reinforces the importance of assessing OHRQoL in this population to promote individualized approaches for each case, as well as the need for referrals and the establishment of public health policies.

Finally, it is crucial to emphasize the need for future research on the correlation between anxiety, depression, and dysplasia severity in OPMD patients. The objective of this assessment is to better understand the psychological impairment associated with the progression of dysplasia, which can aid in developing more comprehensive therapeutic interventions.

Clinically, this investigation may help in the early identification of high-risk patients, allowing a multidisciplinar approach that includes the appropriate management of psychological aspects alongside clinical dysplasia treatment.

Conclusions

This study concludes that, according to the mean OHIP-14 value obtained, a slight change was observed in the OHRQoL of the patients in this sample, with a prevalence of psychological discomfort, psychological disability, and physical pain domains.

Concerning the presence of psychological disorders in patients with OPMD, possible cases of generalized anxiety and the presence of depressive symptoms were identified, besides a significant positive correlation between the perceived OHRQoL and the levels of anxiety and depression. Therefore, these results support future studies to evaluate the quality of life in patients with OPMD in different sociocultural contexts and reinforce the need for multidisciplinary care in monitoring these individuals, to improve psychological and social well-being.