INTRODUCTION

Epoxy resins are widely used as adhesives or coatings in construction, production of sports equipment, cars, boats, airplanes, wind blades, etc.1,2They are a frequent cause of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), being among the most common occupational skin sensitizers in industrialized countries.3,4Epoxy resin based on diglycidylether of bisphenol A is the most widely used and is the main responsible allergen, but sensitization can also develop to other components, including hardeners and reactive diluents.5,6This sensitization is observed in workers who handle unhardened epoxy resin and it happens through direct contact and through airborne exposure.3 An old study from our department showed a frequency of allergic reactions to epoxy resin equivalent to reports from other countries.5 However, there has been a slight increase in the frequency of allergic reactions to epoxy resins in recent years, which we relate to the implementation of a large wind turbine blades production plant in our region. Wind turbines blades production workers represented 40.9% of total patients with ACD to epoxy resin.5,7,8The aim of the present study was to evaluate the prevalence of contact allergy to epoxy resin and its components among wind turbines blades production workers with suspected contact dermatitis as well as to characterize its clinical pre-sentation and its occupational consequences.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective study of the clinical data and patch test results of wind turbine blade production workers with dermatitis studied at the Allergology Department of the Dermatology Service of the Coimbra Hospital and University Center between January 2012 and August 2019. Patients were tested with the European baseline series, epoxy resins components and additional series (Chemotechnique Diagnostics®, Vellinge, Sweden) according to other exposures. Patch tests were applied using Finn Chambers® on Scanpor Tape® for 2 days and the results were read on day-2 or 3 and day-4 to day 7, according to the recommendations of the European Society for Contact Dermatitis.9 Only 1+ or more intense reactions were considered. Occasionally, a semi-open test was performed with products from the workplace, after confirming their pH: A drop of the resins, paints or glues was painted on the tissue tape (Fixomull®), left to dry at air temperature and then applied directly on the back of the patient without any chamber.

RESULTS

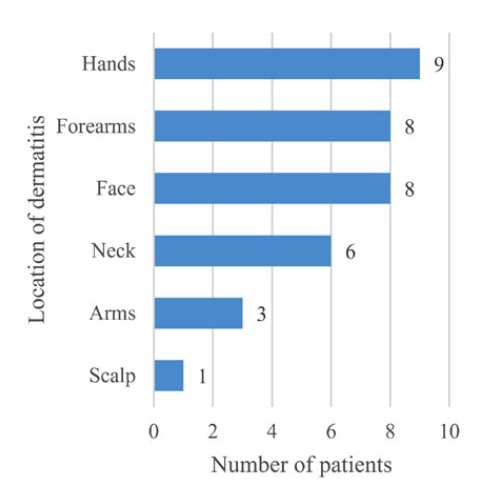

From a total of 3049 patients tested, we identified thirteen wind turbine blade production workers, nine men (69.2%) and four women (30.8%), aged 21 to 56 years (mean 35.9 years ± 8.4), one patient (7.7%) with atopy (asthma). Seven patients (53.8%) had hand dermatitis and airborne dermatitis (face, neck and arms), two (15.4%) had exclusively hand dermatitis and four (30.8%) predo-minantly airborne dermatitis. Regarding the location of the lesions, we found a greater involvement of the hands (n=9; 69.2%), the forearms (n=8; 61.5%), the face (n=8; 61.5%) and the neck (n=6; 46.2%) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Location of dermatitis lesions presented by patch tested wind turbine blades production workers.

All patients handled glues, resins and/or paints in their work activity (preparation or application) and pointed out the chemicals used at work as a triggering factor for injuries, although they used protective equipment that was regularly changed (2 pairs of gloves during direct contact, safety goggles, face masks and insulating suits) and the ventilation of the factory was adequate, as we could document in a visit to the factory. The time in the job until the onset of the dermatitis varied between 1 month and 3 years, with less than 1 year in seven patients (53.8%). In three patients (23.1%) it was not possible to determine the time of exposure prior to the onset of dermatitis (Table 1).

Table 1 Exposure time to onset of dermatitis.

| Time (months) | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| ≤ 1 | 2 |

| 2 - 6 | 3 |

| 7 - 12 | 2 |

| >12 | 3 |

| No information | 3 |

The time from the onset of dermatitis to performing patch tests varied between 5 months and 7 years (Table 2).

Table 2 Time from the onset of dermatitis to patch test.

| Time (months) | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| ≤ 6 | 3 |

| 7 - 12 | 5 |

| 13 - 18 | 2 |

| 18 - 24 | 1 |

| >24 | 2 |

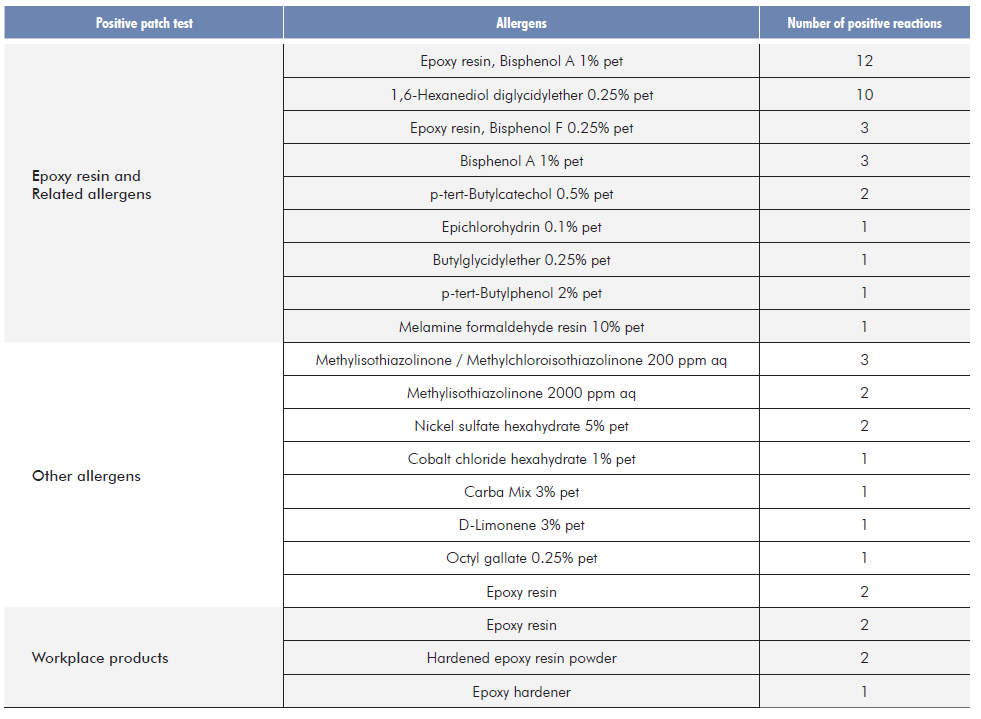

All patients were tested with the baseline series and epoxy resins components, and four patients (30.8%) were tested with additional series. Semi-open tests were performed on three patients (23.1%). Twelve patients (92.3%) had relevant positive patch tests (1+ to 3+) to epoxy resin of bisphenol A 1% pet from the European baseline series, four patients (30.8%) to epoxy resin of bisphenol F 1% pet, ten patients (76.9%) to 1,6-Hexanediol diglycidylether 0.25% pet, three patients (23.1%) to bisphenol A 1% pet, two patients (15.4%) to p-tert-Butylcatechol 0.5% pet, and butyl-glycidylether 0.25% pet, epiclorhydrin 0.1% pet, p-tert-Butylphenol 2% pet and melamine formaldehyde resin 10% pet were positive in one case each. One patient (7.7%) reacted only in a semi-open test with the epoxy resin from workplace. Two patients (15.4%) also reacted to the already hardened epoxy resin powder and one patient (7.7%) reacted to the epoxy hardener from workplace. Six patients (46.2%) had positive patch test reactions to other allergens, namely to methylchloroiso-thiazolinone/methylisothiazolinone 200 ppm aq (n=3; 23.1%), methylisothhiazolinone 2000 ppm aq (n=2; 15.4%) and nickel sulfate hexahydrate 5% pet (n=2; 15.4%), among others (Table 3).

Follow-up in further consultations or by a phone contact to assess the evo-lution of their dermatitis, four patients (30.8%) had to give up their work with significant improvement in symptoms, and three (23.1%) were transferred to another workstation without exposure to epoxy, also improving dermatitis. In six patients (46.2%) it was not possible to ascertain the evolution of complaints.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that all wind turbines blades production workers with suspected ACD reacted to epoxy resin and related allergens. The perception of the health risk associated with chemicals used at work was common to all patients. The time of work exposure necessary to develop complaints of dermatitis was short. This short period of time to raise awareness of epoxy resins already appears on the Portuguese occupational diseases list (Regulatory Decree No. 76/2007, of 17 July), which imposes only 15 days of exposure to epoxy resins for contact dermatitis to be considered an occupational disease.10 The lag time until diagnosis was long, which can translate a devaluation of complaints by worker and the occupational and family doctors. In our study, in addition to direct exposure, airborne exposure was an important form of sensitization to epoxy products, which is in line with other studies.1,3Although resins themselves are the most important sensitizers, several other curing agents and reactive diluents have been described as contact allergens.5,6,11In our study, 1,6-hexanediol diglycidylether, commonly used as a resin diluent, proved to be an important sensitizer in ten patients (76.9%). This has been most often associated with airborne dermatitis due to its high volatility, however, we have not been able to find this association.11 We emphasize the need for patch testing with components currently in use in epoxy resins to improve the diagnosis of contact allergy.5,11One patient reacted only to the epoxy resin from the workplace, which highlights the need for patch testing with products used at work to increase diagnostic sensitivity.11 During a visit to the workplace, we could see the implementation of protective measures for workers, mostly based on the use of personal protective equipment. However, we found that the tasks performed impose a long exposure time which, associated with the high sensitization potential of epoxy resins and their permeation through gloves and other equipment, can explain the high frequency of ACD in wind turbines blades production workers.2,4Sensitization and contact allergy is attributed to the unhardened resin, however two patients had positive patch tests to the hardened resin powder, which indicates that there is some danger eventually related to incomplete polymerization of epoxy compounds.3 Resolution of the dermatitis observed in seven patients (53.8%) who left the company or were assigned to another workstation in the same company demonstrates the good prognosis when the exposure ceases, corroborating other studies.5,7,8However, allergy to epoxy resin has considerable consequences. A total of 30.8% of the patients in the current study have had to change jobs; this has affected their income negatively, and they are limited in their choice of work. We also emphasize the importance of the occupational disease participation that contributes to the best epidemiological study of occupational diseas12 gives patients the right to disability repair which, however, takes long and is often incomplete in Portugal.

CONCLUSION

With this study we found that epoxy resin and its components are the main cause of dermatitis among wind turbines blades production workers and they can sensitize and induce contact dermatitis both through direct contact and airborne exposure. Even with the use of adequate personal protective equipment, exposure to epoxy resins in this sector of activity is high enough to sensitize the workers. We reinforce the importance of improving personal protective equipment and, especially of using collective protection measures to minimize exposure. In addition, occupational physicians should instruct workers to follow skin care programs to decrease the possibility of sensitization and should implement health surveillance protocols that allow early diagnosis. A worker sensitized to epoxy resin is permanently incapacitated for his usual work, so the participation of occupational disease becomes essential.

Apresentações

15º Fórum Nacional de Saúde Ocupacional, 21 e 22 de novembro de 2019, Lisboa, Portugal