Introduction

Although most COVID-19 patients recover completely without sequelae, some require evaluation and management for persistent or new symptoms.1 Long COVID, post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection, or post-COVID syndrome are terms introduced in the literature to describe illness in persons who report persistent symptoms post-acute COVID-19. 2-3 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention propose the term post-COVID conditions (PCC) for symptoms that develop during or after COVID-19, continue for three months from the onset, and are not explained by an alternative diagnosis. 4 Data has been consistent in suggesting that symptoms and post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 can persist even in mild to moderate disease, challenging primary care to determine the medium and long-term effects of this disease. 2-3

In this cross-sectional study, we aimed at estimating the proportion of COVID-19 patients that presented PCC, describing their baseline characteristics and main persisting symptoms.

Methods

We interviewed adult patients who had recovered from mild to moderate COVID-19 confirmed by PCR testing from November 2020 to April 2021 at the Primary Care Health Unit Barão Nova Sintra, Porto, using a structured questionnaire, twelve to sixteen weeks after disease onset.

Our health unit is localized in the centre of the second biggest city in the country, it serves approximately 12,300 urban patients. Throughout the COVID outbreak, we maintained a combined response of face-to-face consultation and telephone surveillance through a national COVID-19 surveillance platform (TraceCOVID). 5

Inclusion criteria were a positive PCR test for SARS-COV-2, more than eighteen years old, and active consent.

Exclusion criteria were age under eighteen years, the impossibility of establishing a telephone call after three attempts at different times on the same day, institutionalization, no active enrolment at the unit (less than one medical or nursing contact in the last three years), refusal, dying during data collection period or be under end-of-life care. We also exclude patients who had severe COVID-19 defined by British Thoracic Society Guidance (which includes intensive care unit or high-dependency unit admission, patients discharged with a new oxygen prescription, patients with protracted dependency on high inspired fractions of oxygen, continued positive pressure ventilation and bi-level non-invasive ventilation). 6

Patients were offered an assessment by a medical team after ambulatory COVID-19 recovery or discharge from the hospital. Demographic and clinical characteristics were extracted from the TraceCOVID. The modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea scale was used to evaluate breathlessness. The terms ‘feeling anxious’, ‘memory disturbance’, and ‘feeling depressed’ were used according to the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC-2).

Associations between baseline characteristics and PCC were evaluated by Pearson’s chi-squared test. Multiple logistic regression models were built to explore which baseline characteristics were associated with a higher incidence of PCC; odds ratios (OR) with (95% CI) were estimated. Stata was used for analyses. Oral informed consent was obtained from all the participants. The study had a favorable opinion by the Ethics Committee for Health of the Northern Regional Health Administration (CES ARSN).

Results

Of the 738 patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV--2 in the study period, we excluded 241 (32.6%) patients: 85 (35.3%) were younger than 18 years, 57 (23.7%) did not answer the telephone call, 51 (21.2%) were nursing home residents, 13 (5.4%) had no active enrolment at the unit, 12 (5.0%) refused to provide consent, 10 (4.1%) had died, eight (3.3%) were under end-of-life care and five (2.1%) had severe COVID-19.

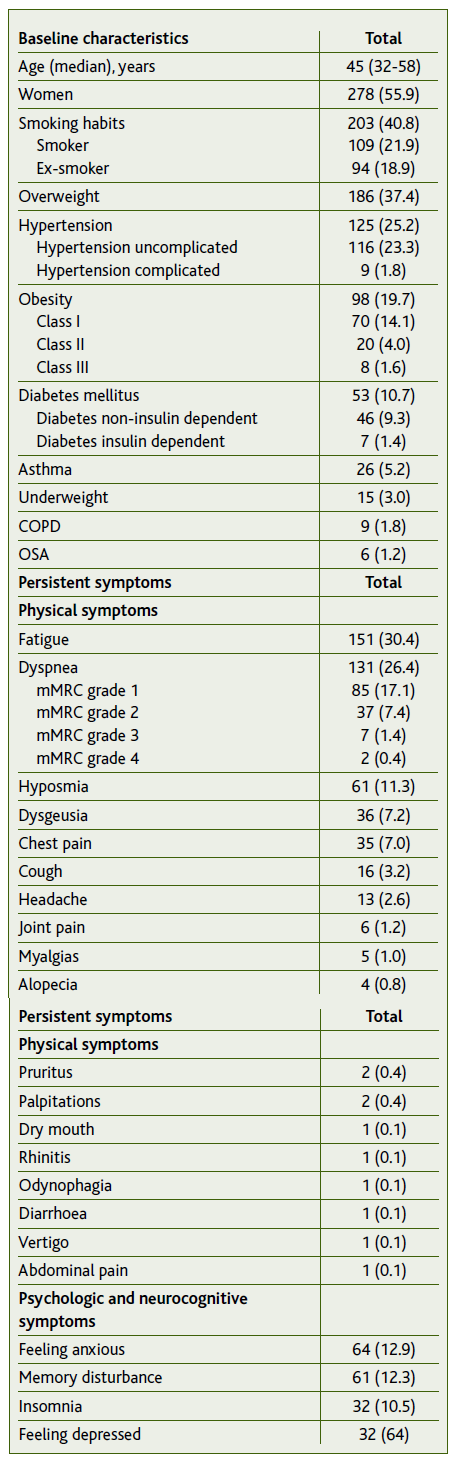

We included 497 (67.4%) patients, mainly women (55.9%), with a median age of 45 (32-58) years. All included patients were unvaccinated against COVID-19 since at the time the vaccination wasn’t generalized to the general population. The most prevalent risk factors were smoking habits (n=203, 40.8%) and excess body weight (n=186, 37.4%). Two hundred and sixty-one (52.5%) patients reported having completely recovered from COVID-19. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the study population and the main features in the post-COVID infection medical assessment.

Discussion and conclusion

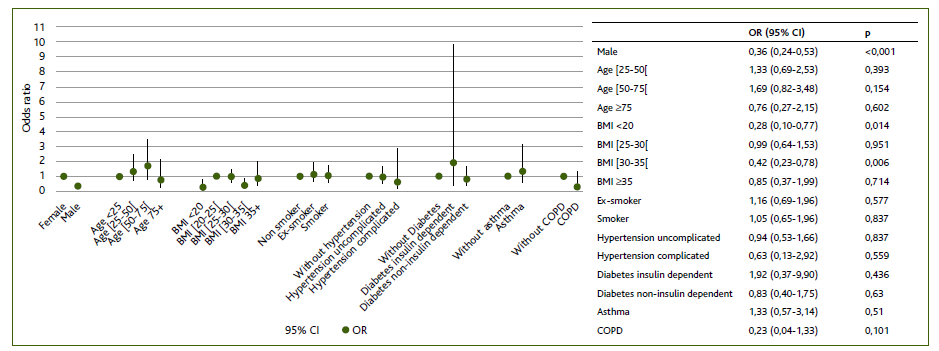

The cumulative incidence for PCC twelve to sixteen weeks after disease onset, in mild to moderate COVID-19, was 47.5% (n=236). The most frequent symptoms were fatigue (n=151, 30.4%) and dyspnea (n=131, 26.4%). After adjusting for covariables (Figure 1 male gender was found to be associated with lower odds of PCC (OR=0.36, 95% CI: 0.24-0.53, p<0.001). Body Mass Index (BMI) <20 (OR=0.28, 95% CI: 0.10-0.77, p=0.014) and BMI [30-35[ (OR=0.42, 95% CI: 0.23-0.78, p=0.006) seemed to have less persistent symptoms when compared to the BMI [20-25[. No other baseline demographic or clinical features were found to be significantly associated with PCC.

Figura 1 Multiple logistic regression model for the outcome of at least one persistent symptom 12 to 16 weeks after mild to moderate COVID-19 onset. The 95% CI of the odds ratios has been adjusted for multiple testing. Definition of abbreviations: BMI = Body mass index; COPD = Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CI = Confidence interval; OR = Odds ratios; p = p-value.

Series have reported the incidence of persistent symptoms ranging from 40 to 90% of patients as observed in our study. However, data are often limited by a lack of control groups and surveillance, selection biases, the severity of infection, as well as follow-up and characteristics of the clinical evaluation. 7 Some studies suggest that the female sex may be at higher risk for certain PCC manifestations, which require further studies to clarify. However, much remains ambiguous about PCC, particularly its risk factors. 8

Limitations in our study include symptoms related to other conditions that may have occurred after diagnosis, heterogeneity in the validation of symptoms among the medical team, anthropometry collected by a telephone call when outdated from the clinical record, as well as the relatively small sample size to detect minor associations.

In conclusion, our study suggests that PCC persists in a large subset of non-severe diseases. Physicians should continue to monitor these patients in order to identify and treat post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection, particularly in what concerns primary care. It would be useful to repeat our study in a vaccinated population to assess the incidence of PCC.

Patient’s consent

Oral informed consent was obtained for the publication of this study with approval by the institution’s Ethics Committee.

Authors contribution

Conceptualization, TGO, HSA, IBP, MJF, MDA, ABM, and AFB; methodology, TGO, HSA, IBP, MJF, MDA, ABM, and AFB; software, TGO, HSA, IBP, MJF, MDA, and CC; validation, TGO, HSA, IBP, MJF, MDA, CC, ABM, and AFB; formal analysis, TGO, HSA, IBP, MJF, MDA, and CC; investigation, TGO, HSA, IBP, MJF, and MDA; resources, TGO, HSA, IBP, MJF, MDA, CC, ABM, and AFB; data curation, TGO, and CC; writing - original draft preparation, TGO, HSA, IBP, MJF, and MDA; writing - review and editing, TGO, CC, ABM, and AFB; supervision, CC, ABM, and AFB. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.