Introduction

Strongyloides stercoralis is an intestinal nematode that colonizes and reproduces in the upper small intestinal mucosa [1]. Infection in immunocompetent hosts is self-limited but in immunocompromised patients it can be complicated and cause hyperinfection [1]. Herein, we report a case of hyperinfection syndrome with gastric and duodenal involvement and complicated with syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH).

Case Report

The patient is a 60-year-old female from the Dominican Republic who had lived in Spain for 10 years and was diagnosed with acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura with central nervous system involvement. Two months after the diagnosis she was admitted due to exacerbation of her illness with severe thrombocytopenia, in this case without neurologic symptoms. The evolution was slow, requiring high doses of corticosteroids, several sessions of plasma exchange, and rituximab to achieve remission of the hematological disease. After finishing plasma exchange and when the corticoids were being withdrawn, the patient began to experience persistent pyrosis, nausea, vomiting, and oral intolerance. Physical examination highlights epigastric tenderness. Blood tests showed hyponatremia (sodium 119 mEq/L, reference values 136-146) and leukocytosis with eosinophilia (20,790 leukocytes/µL with 18% of eosinophils). The patient presented euvolemic hyponatremia with criteria of SIADH (plasma osmolality 258 mOsm/kg, reference values 275-300; urine osmolality 588 mOsm/kg, reference values 50-1,200). Upper endoscopy was performed, and it showed esophageal, gastric, and duodenal mucosa with edema and erythema (Fig. 1). Moreover, there were superficial erosions and thickened folds in the duodenum. Gastric and duodenal biopsies were taken.

Fig. 1: Upper endoscopy image showing esophageal (a), gastric (b), and duodenal (c) mucosa with edema and erythema.

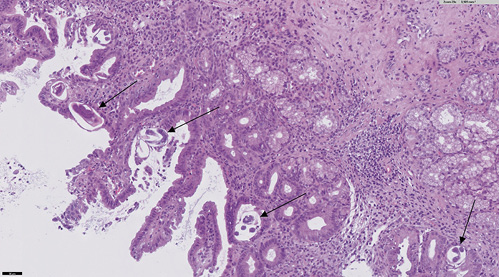

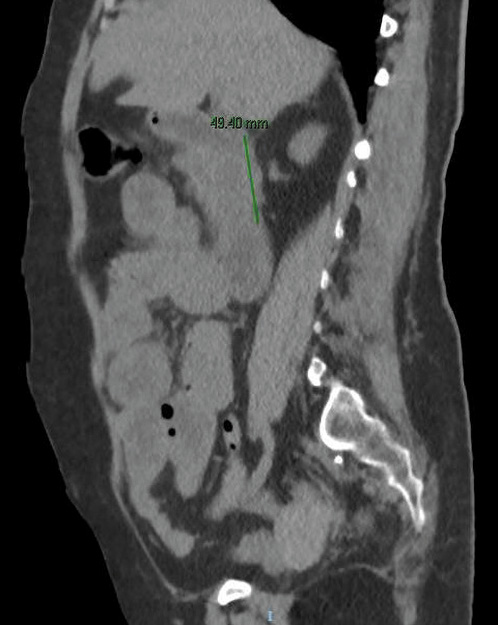

An abdominal computed tomography was performed (without intravenous contrast because the patient was allergic). It showed dilation of the second and third duodenal portions, with wall thickening and rarefaction of the adjacent fat, in relation to inflammatory changes that seemed to affect a segment of about 5 cm (Fig. 2). Symptoms persisted, so a magnetic enteroresonance was done and mild dilation and slight inflammatory changes were found which affected a segment of about 3 cm of the second duodenal portion. The involvement seemed to have improved since the previous computed tomography. The histological study of gastric and duodenal biopsies showed colonization of acini by S. stercolaris in both the antrum and the duodenum (Fig. 3). A stool test confirmed infection with this parasite. Treatment of S. stercolaris hyperinfestation with ivermectin and albendazole was initiated, with progressive tolerance and clinical improvement. She completed 18 days of treatment with antihelminthic drugs until repeated stool tests showed no presence of the parasite. Five months later the patient had a new exacerbation of acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, which was treated again with glucocorticoids, plasma exchange, and rituximab, but did not show any gastrointestinal symptoms and stool tests remained negative with prophylaxis with ivermectin.

Fig. 2: Abdominal computed tomography image without intravenous contrast showing dilation of the second and third duodenal portions, with wall thickening and rarefaction of the adjacent fat, in relation to the inflammatory changes that seem to affect a segment of about 5 cm.

Discussion

S. stercolaris is a human parasite that is endemic in tropical, subtropical, and temperate regions like Southeastern USA, South Asia, Latin America, and sub-Saharan Africa [2-6]. The incidence of strongyloidiasis is increasing in many developing countries and it is facilitated by international travel and immigration [3]. It is estimated that about 30-100 million people are infected worldwide [2, 4].

The lifecycle of S. stercolaris is complex because it completes its entire cycle within the human host [2, 4]. Free-living larvae penetrate the skin and migrate to the lungs via venous circulation [2-4, 6, 7]. They break into the alveolar spaces, ascend through the tracheobronchial tree, and are swallowed with sputum [4, 6, 7]. After reaching the gastrointestinal tract, they invade the small bowel and live buried in the crypts [2, 3, 6, 7]. The most affected sites are the duodenum and the upper jejunum, where the larvae develop into adult worms [2-4, 7, 8]. Adult female worms usually reside under the intestinal mucosa, where they shed eggs [3]. Fertilized eggs produce new larvae that exit into the intestinal lumen and are excreted in the feces [3, 4, 6, 7]. The life cycle includes autoinfection through the intestinal mucosa or perianal skin, especially in immunocompromised hosts [2-4].

Immunossuppression can lead to hyperinfection syndrome and disseminated disease [2-5, 7]. Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome occurs when the normal life cycle is augmented, resulting in massive infection of the gastrointestinal tract, the circulatory system, and the lungs [9]. Disseminated strongyloidiasis is when the parasite extends outside of the traditional lifecycle and invades the central nervous system, the liver, the kidneys, and other organs [2-5, 7, 9]. However, involvement of the stomach has relatively rarely been reported [1, 5, 7]. Disseminated strongyloidiasis often occurs in hyperinfection syndrome [9]. Hyperinfection syndrome can progress to organ failure and death [3, 5]. Hematologic malignancies, transplantation, immunosuppressive drugs such as corticosteroids, human T-lymphotropic virus type-1 (HTLV-1), HIV-1, and another immunosuppressed states are risk factors for S. stercolaris hyperinfection syndrome [2-4].

Symptoms are frequently nonspecific, like vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and weight loss [3, 8], although half of the infections are asymptomatic [2, 4, 6]. Malabsorption syndromes, gastrointestinal bleeding, intestinal obstruction, SIADH, and sepsis have also been described [2-4, 6, 8]. SIADH has been related to systemic strongyloidiasis hyperinfection and likely attributed to central nervous system or pulmonary involvement, although the mechanism is not clear [4, 10]. Tariq et al. [4] reviewed previous reported cases of SIADH in Strongyloides infection and found only 8 cases. All of them recovered with antihelminthic treatment [4].

The relatively nonspecific clinical and imaging features and the low sensitivity of routine parasite tests make the diagnosis challenging and delayed [4, 10]. Peripheral eosinophilia is variable [4, 8, 10]. Definitive diagnosis is usually made on direct visualization of larvae in stool or in clinical specimens such as intestinal aspirates or biopsies from endoscopy [10]. Single fecal sample examination has a low sensitivity due to the low parasite burden or intermittent excretion [4, 10]. Repeated examinations with up to 7 stool samples may increase the sensitivity [4, 10]. Serologic tests may be used to overcome the limitations of stool tests, with a greater sensitivity and a high negative predictive value, which is useful for exclusion of S. stercoralis infection [11]. The most common endoscopic findings are mucosal edema, erythema, friability, white villi, erosion, and pseudopolyps [8].

The treatment of choice for S. stercolaris hyperinfection is ivermectin [2]. The alternatives are benzimidazole-based agents like albendazole and thiabendazole [2]. The optimal duration of antihelminthic treatment for hyperinfection or disseminated strongyloidiasis is uncertain [11]. It is recommended that the treatment be continued until the symptoms have resolved and stool tests are negative for at least 2 weeks [11]. For patients with persistent immunosuppression whose symptoms have resolved, ivermectin once monthly can be given as prophylaxis [11].

To conclude, we present the case of a patient with hyperemesis and oral intolerance in relation to duodenal inflammation caused by S. stercolaris. She suffered from reactivation of chronic infestation due to immunosuppression in the context of the treatment of purpura thrombotic thrombocytopenic. S. stercoralis infection and hyperinfection syndrome are rare in our environment. Apart from the low prevalence, the diagnosis of the infection is challenging. The lack of specific clinical features results in frequent misdiagnosed cases. Moreover, in this patient there was gastric involvement and SIADH, which have rarely been reported.