Introduction

Exacerbation of ulcerative colitis (UC) is a frequent cause of hospitalization in a gastroenterology service, commonly with rectal symptoms relating to ulcerative proctitis. Infectious proctitis (IP) shares common clinical and endoscopic findings with ulcerative proctitis, thus necessitating methodical differential diagnosis.

Men who have sex with men (MSM) present increased risk of IP and, in this population, sexually transmitted infections are the leading cause of IP [1]. Recent data suggest a rise in the frequency of IP in this population [2]. The most commonly involved pathogens are Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, herpes simplex virus 2, and Treponema pallidum[3].

Infectious etiologies of proctitis should be searched whenever a patient presents with presumed ulcerative proctitis. In addition to a complete clinical history and physical examination, a complete microbial study should be performed [4]. Stool samples for culture and molecular testing as well as serology and pathology may be useful to determine a causative agent [5].

The authors present the case of a MSM who presented with rectal symptoms presumed to be related to a relapse of previously diagnosed UC. Cytomegalovirus (CMV), Blastocystis hominis and Chlamydia trachomatis were identified after extensive microbial workup. The aim of this report is to focus on the importance of microbial testing for an effective differential diagnosis between inflammatory bowel disease exacerbation and its infectious mimics.

Case Report/Case Presentation

In May 2018, a 62-year-old male presented at the emergency department with a 3-day history of bloody diarrhea (>10 bowel movements per day with blood in 3/4 of bowel movements), tenesmus, urgency, and recent weight loss. His symptoms occurred predominantly at night. The patient was followed at the gastroenterology clinic since 2015 for UC, in remission under oral and topical salicylates. His medical history was also remarkable for HIV infection diagnosed in 2011, currently under antiretrovirals (abacavir/lamivudine + raltegravir), with undetectable viral load and good CD4+ T lymphocytes counts (632/μL); perforated CMV colitis in 2014, resulting in left hemicolectomy; cured hepatitis B in 2012, cured syphilis in 2003; chronic kidney disease, and rheumatic valve disease. The patient reported unprotected anal sex with men. The subject lived in an urban area and denied recent travels.

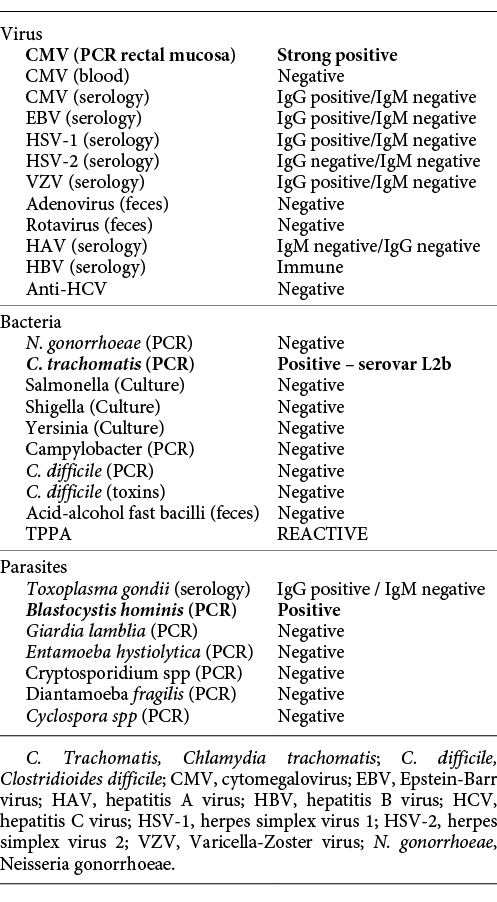

On physical examination, the patient had no fever, was hemodynamically stable (blood pressure 127/60 mm Hg, heart rate 64 beats/min) and had only tenderness on lower abdominal quadrants. He had no adenopathy. Laboratory results revealed new-onset anemia (haemoglobin 11 g/dL), mild hypoalbuminemia of 35 g/L (normal range 38-51 g/L), and mild elevation of inflammation markers, with a C-reactive protein (CRP) of 40 mg/L (normal range <3 mg/L). Abdominal radiograph was unremarkable. Rectosigmoidoscopy displayed loss of normal vascular pattern, edema, erythema, exudation, and coexistence of deep and superficial ulceration localized to the distal rectum, with an endoscopic Mayo subscore of 3 (Fig. 1). Biopsies showed moderate chronic active proctitis, with cryptitis but no crypt abscesses or granulomas. There was no evidence of cytopathic effects of CMV infection. Immunohistochemistry for CMV was negative. Workup for infectious causes is resumed in Table 1.

Fig. 1 Rectosigmoidoscopy performed upon admission. Distal rectum revealing loss of normal vascular pattern, edema, erythema, exudation, and superficial ulceration.

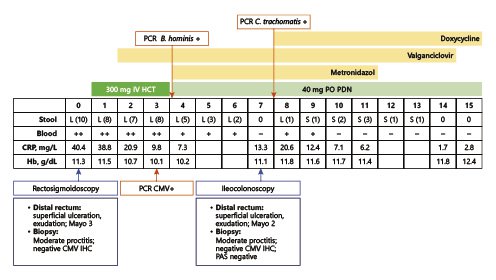

The patient was hospitalized, and intravenous glucocorticoids (hydrocortisone 300 mg IV perfusion over 24 h, with posterior switch to oral therapy) were instituted for presumed severe relapse of ulcerative proctitis. After 3 days of intravenous steroids, he had persistent bloody diarrhea (5 bowel movements per day, ≥3 occurring at night). An extensive microbiologic workup was performed. Opposite to the IHC study, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing was positive for CMV, and the patient initiated a 14-day course of valganciclovir. Moreover, B. hominis was identified by PCR of fecal samples, and antimicrobial treatment with metronidazole was started. The patient had a significant improvement, with fewer stools and improvement of rectal bleeding and recovery of hemoglobin values. The patient underwent ileocolonoscopy 7 days after admission, which displayed a slight improvement of rectal lesions (Fig. 2), with loss of normal vascular pattern, circumferential erythema, and exudation (Mayo endoscopic subscore 2). Biopsies of the rectal mucosa presented with moderate chronic proctitis; CMV immunohistochemistry was negative as was staining for Periodic Acid of Schiff-positive organisms. Furthermore, PCR of rectal exudates allowed the identification of Chlamydia trachomatis serovarL2b. Rectal lymphogranuloma venereum was diagnosed, and the patient was started on doxycycline. Anal condilomatous lesions were also present (Fig. 3). Biopsy revealed cytopathic characteristics of human papillomavirus infection, without signs of dysplasia. A chronogram of the patient’s clinical evolution and clinical workup is shown in Figure 4. Upon discharge, the patient had no symptoms, with normalized stool frequency and no rectal bleeding. He continued follow-up in the outpatient clinic and remained with remitting disease after 24 months under oral and topical salicylates.

Fig. 2 Ileocolonoscopy performed 7 days after admission. Distal rectum displaying loss of normal vascular pattern, circumferential erythema, and exudation.

Fig. 3 Anal condilomatous lesion. Biopsy revealed cytopathic lesions typical of human papillomavirus infection.

Fig. 4 Chronogram of clinical and analytical evolution. Dates and duration of therapeutics are also depicted. Days of hospitalization are counted in relation to admission (day 0). Stool: L, liquid; S, soft; number of bowel movements between round brackets. Blood in stools: ++ significative bleeding; + residual bleeding; - no bleeding; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CRP, C-reactive protein; Hb, haemoglobin; HCT, hydrocortisone; IHC, immunohistochemistry; IV, intravenous; PAS, Periodic Acid of Schiff; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PDN, prednisolone; PO, per os.

Discussion/Conclusion

UC is a chronic inflammatory disease of unknown etiology. Extensive research in this field has postulated that UC derives from aberrant interactions between the immune system and environmental factors, such as the colonic microbiota, in a genetically predisposed host [6]. Typically, it follows a relapse-remitting course, and up to a quarter of patients have acute severe flares requiring hospitalization [7]. Infectious causes of colitis are important mimics of a pure inflammatory flare of UC. The evaluation of risk factors for infection with agents of colitis (immunosuppression, recent travels, sexual behavior, recent antibiotics) is essential [4, 7]. Venereal agents constitute the most common cause of IP [3]. Testing for these agents is advised for patients with known risk factors [5]. HIV infection should also be excluded [5]. The European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization recommends systematic microbiological testing in patients with relapsed UC, with particular focus in exclusion of C. difficileand CMV infections, which are known to impose more risk of complications and worse prognosis [4, 7].

This case is paradigmatic of the importance of an extensive diagnostic workup of mimics of UC flares, particularly infectious causes. We performed a broad diagnostic workup aiming to include several infectious etiologies of proctitis. During the course of this investigation, several infectious candidates for proctitis were identified, specifically CMV, lymphogranuloma venereum caused by C. trachomatis, and eventually B. hominis. The identification of one of these agents as the sole causative agent of this case of proctitis is difficult and it was guided by the integration of pathological findings and clinical improvement upon different treatments.

The extensive workup retrieved strong positive results for CMV PCR on rectal samples. Pathology did not show cytopathic effects of CMV and IHC was negative. Attending to the strong positivity of mucosal PCR, it was considered as clinically significant cause of infection [8], and treatment with valganciclovir was started.

Rigorous scientific data have yet to differentiate B. hominis as an innocent bystander or as an infectious agent. Some studies have described a potential pathogenic role for B. hominis. This parasite has been associated with diarrhea in immunocompromised patients, most importantly in individuals with HIV infection [9]. Nevertheless, most authors warrant treatment when other causes for the symptoms have been excluded, particularly in immunocompromised subjects.

Association between this agent and IBD is not completely understood. In 1991, abundant infestation was described as causative of relapse of UC. Treatment with metronidazole resulted in significant improvement of patient’s complains [10]. Also, it was found that patients with active disease (either persistently or intermittently) demonstrate higher frequencies of infestation [11, 12]. Nevertheless, the available data is conflicting. Nagler et al. [13]suggest that B. hominis is not an enteropathogen, and that its presence does not correlate with symptoms or evolution of IBD. More recently, no association was established between the presence of the parasite and IBD status (remission or flare). Moreover, in that study, the presence of B. hominis was a predictor of milder disease [14].

B. hominis was detected upon broad parasitological workup. Taking into account the existing evidence reporting the role of B. hominis in exacerbation of UC, in a HIV patient not responding to glucocorticoid, the risk-benefit relationship favors treatment. Although we cannot univocally indicate the parasite as the sole infectious agent, we cannot exclude its role in this particular case. The patient had a good response to metronidazole, which suggests that B. hominis was at least acting in synergy with other infectious agents.

Lymphogranuloma venereum was also diagnosed in this patient. Proctitis or proctocolitis is the most common manifestation of LGV, particularly in men who have sex with men and HIV, and its frequency has been rising [2, 15, 16]. Clinical manifestations resemble that of ulcerative proctitis. Endoscopic appearance is that of UC, with rectal ulcers, erythema and mucosal friability [15]. Confirmation of LGV is commonly obtained through PCR. In this case, the infection was confirmed, and genotyping allowed the identification of serovar L2b, which is predominant across LGV proctitis [15]. The patient was treated with oral doxycycline for 21 days. Resolution of rectal bleeding and normalization of bowel habits was registered. Treponema pallidum was also equated as co-infection agent, according to positive TPPA assay. Nevertheless, given the past history of syphilis and clinical improvement with treatment for other agents, TPPA positivity was regarded as marker of past exposure.

This report describes a patient with a severe relapse of ulcerative proctitis and the co-occurrence of multiple infectious agents acting as trigger or mimics of a pure inflammatory relapse. The differential diagnosis is often difficult and must be carefully supported by integration of clinical, analytical, microbiologic, and histologic data. This work highlights the importance of remaining aware of possible infectious etiologies, and the value of an extensive microbiological investigation, particularly in patients with known risk factor for IP.