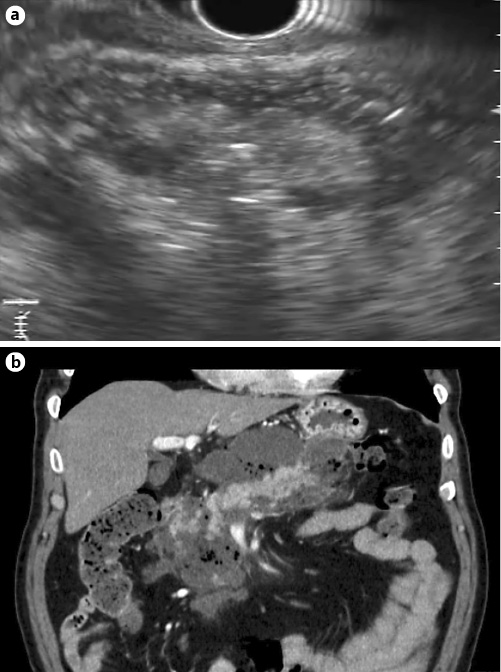

A 74-year-old male patient presented with epigastric pain radiating to the back, nausea, and vomiting. Laboratory tests revealed elevated amylase (873 U/L), and abdominal ultrasound confirmed the presence of gallstones. Mild lithiasic acute pancreatitis was established in the first 48 h according to the revised Atlanta classification. However, during the second week in hospital, the patient showed persisting vomiting and fever. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan displayed a complex peripancreatic collection surrounding the head, body, and tail of the pancreas, that contained gas, fluid, and necrotic pancreatic tissue on the unciform process (Fig. 1). Infected necrotizing acute pancreatitis was diagnosed, and broad-spectrum antibiotics were started. Invasive drainage intervention was considered, bearing in mind the clinical evolution and the necessity of a well-defined collection wall.

Fig. 1: a EUS showing a 14-cm, walled-off pancreatic necrosis (week 4). b A complex peripancreatic collection surrounding the head, body, and tail of the pancreas, and containing gas, fluid, and necrotic pancreatic tissue on the unciform process on an abdominal CT scan (week 2).

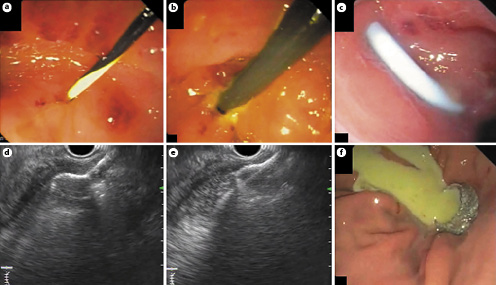

After 4 weeks, the patient maintained the initial symptoms, although clinically stable and without organ failure, under optimal medical therapy. CT scan and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) revealed a 14-cm, infected, walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WON), with a well-circumscribed wall and a mixed solid (estimated 70%) and liquid content (Fig. 1). Considering the size of the collection, EUS-guided drainage was performed by a multiple transluminal gateway technique (MTGT), using a linear echoendoscope (GF-UCT180, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) (Fig. 2). At first, a plastic double-pigtail stent (8.5 Fr/6 cm) was placed on the pyloric antrum, through direct transgastric puncture with a 19-G needle, followed by a 0.035-inch guidewire insertion. A 6-Fr cystotome was used to dilate and create access. Following plastic stent deployment, minor purulent drainage was observed. Taking into account the size of the collection, the prospect of insufficient drainage and the future possibility of a direct transluminal endoscopic necrosectomy (DEN) being performed, a second stent, a lumen-apposing metal stent (LAMS) (Hot AXIOSTM, 15 × 10 mm, Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) was positioned through the gastric body during the same intervention, followed by abundant pus drainage. Acknowledging adequate primary drainage in a clinically stable patient, a nasocystic catheter was not placed.

Fig. 2: Primary endoscopic procedure. a Guidewire insertion after direct EUS-guided transgastric puncture of the pyloric antrum. b A cystotome was used to dilate and create access. c Placement of aplastic double-pigtail stent. d, e EUS-guided deployment of the distal flange of LAMS. f Endoscopic view of the correctly placed LAMS exhibiting pus drainage.

After the procedure, the patient showed partial clinical improvement, maintaining intermittent epigastric discomfort, nausea, and early satiety.

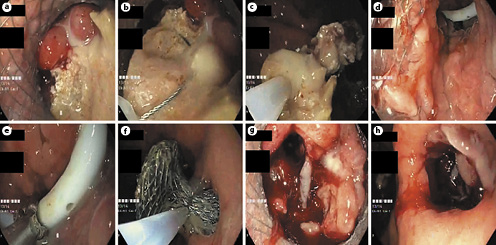

Six weeks later, a secondary endoscopic intervention using a gastroscope (GIF-H190, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) allowed the removal of all the necrotic debris via DEN, with a water-pump system irrigation and a snare (Fig. 3). The stents were removed during the procedure using rat-tooth grasping forceps for the plastic stent and a snare for the LAMS.

Fig. 3: Secondary endoscopic procedure. a Endoscopic view through the previously placed LAMS of the necrotic tissue inside of the peripancreatic collection. b, c Direct transluminal endoscopic necrosectomyusing a snare. d Endoscopic view of the inside of the collection after removal of the necrotic debris, revealing communication between the 2 placed stents. e Plastic stent removal using arat-tooth grasping forceps. f LAMS removal using a snare. g Endoscopic view of the inside of the collection after removal of necrotic debrisand the plastic stent. h Endoscopic gastric view after LAMS removal.

The patient was followed up at another hospital and was only transferred to perform endoscopic procedures. An earlier timing of the second procedure was initially programmed, but was delayed by logistical interhospital arrangements.

Drainage and/or debridement is recommended for patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis and infected necrosis [1, 2]. EUS-guided drainage has been increasingly used to treat infected WON, involving transmural placement of plastic or self-expandable metal stents [1-3]. The use of LAMS, besides allowing further DEN, possibly contributes to more efficient drainage, with less and shorter procedures [3]. MTGT aims to ease the drainage and minimize the number of necrosectomies, especially in large and multiple WON or when there is an otherwise suboptimal response [1, 4-5].