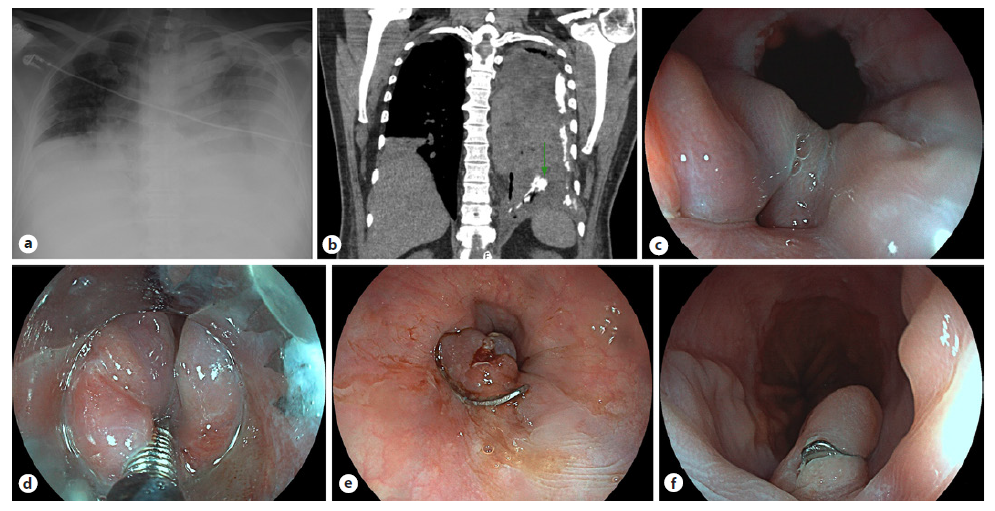

A 74-year-old woman, with the history of obesity (body mass index: 38.05 kg/m2), obesity-hypoventilation syndrome, and hypertension, was referred to endocrinology consultation due to symptomatic recurrent hypoglycemia for 15 years with worsening during the last 4 months. Computed tomography revealed a 2-cm hypervascular pancreatic isthmus mass compatible with a neuroendocrine tumor. Fasting insulin (53 µIU/mL, normal range: 3-25) and C-peptide (5.23 ng/mL, normal range: 0.93-3.73) were elevated during severe hypoglycemia, allowing the diagnosis of insulinoma. Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) was consistent with a neuroendocrine tumor adjacent to the main pancreatic duct (MPD; shown in Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Hypoechoic 18-mm lesion in the pancreatic isthmus, in close proximity to the MPD (arrow, a) and to the splenicmesenteric confluence (arrows, b). The lesion is hypervascular (color Doppler, b) and reveals a predominantly blue elastography pattern (c). These features are compatible with a neuroendocrine tumor.

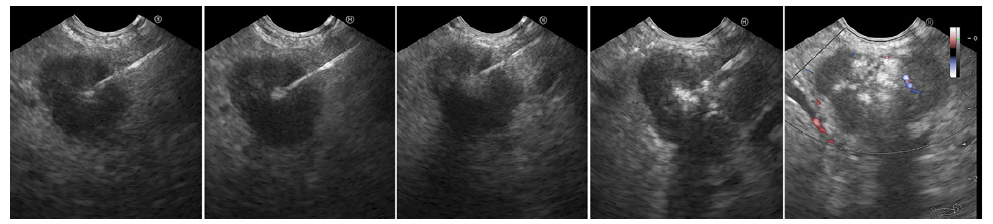

GaDOTA-NOC-PET was otherwise unremarkable. Diazoxide was started with inpatient dose titration to 150 mg three times daily (t.i.d.). However, she developed a hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome. A lower dose was restarted (50 mg t.i.d.), but generalized edema developed. Considering these adverse events in a patient unfit for surgery, diazoxide was suspended and EUS-guided alcohol ablation (EUS-AA) was performed. Using a lineararray echoendoscope (EG-3270UK Slim Ultra-sound Video Endoscope, Pentax, Tokyo, Japan; HI VI-SION Preirus Hitachi Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan) and a 25-gauge needle (EchoTip, Wilson-Cook, Win-ston-Salem, NC, USA), a total of 0.9 mL of absolute alcohol (fractions of 0.1 mL, three passes) was injected with partial hyperechoic filling (shown in Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. First EUS-guided alcohol ablation session. A hyperechoic filling of the tumor is noticed from left to right with remaining hypoechoic areas (right).

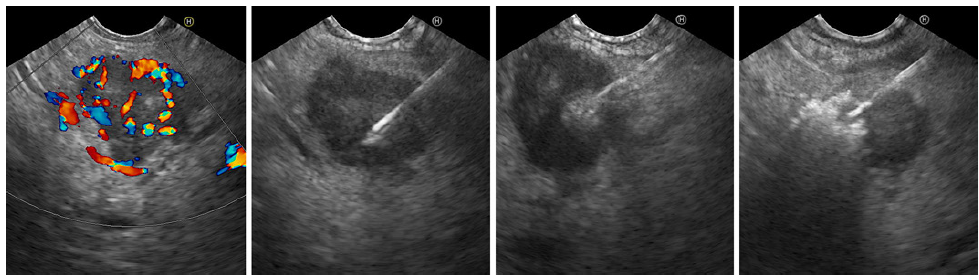

Two mall hypoechoic areas were left untreated to prevent MPD injury. She experienced incomplete response and underwent a second ablation, 3 months later, with equal injection volume (five passes). Two small MPD-adjacent hypoechoic areas persisted (shown in Fig. 3). Prophylactic rectal indomethacin and intravenous hydration were administered. Prophylactic antibiotics were not used. She was discharged after glycemic profile stabilization, 8 and 3 days following the first and second sessions, respectively. No adverse events or further hypoglycemia occurred. Fasting insulin normalized. The patient remains asymptomatic after 6 months. Since symptom relief was the treatment goal and given the very low risk of malignant transformation, no further imaging was performed.

Fig. 3. Residual hypervascular lesion at the start of the second EUS-guided alcohol ablation session (color Doppler, left). Hyperechoic tumor filling is shown from left to right.

Pancreatic insulinomas are rare tumors with an incidence of 4 cases per million per year [1]. They are more frequent in the pancreatic head and often have indolent courses [2]. Surgery is the treatment of choice [3]. Medical therapy is considered in poor surgical candidates, diazoxide being the most used. However, side effects are frequent and the underlying cause is not addressed [4].

Insulinoma EUS-AA was described in 2006 [5]. Reported cases were systematically reviewed, with a total of five pancreatic neck insulinomas submitted to EUS-AA [2]. The median insulinoma size was lower than ours (13 vs. 18 mm), and still the median alcohol injection volume was larger (1.55 vs. 0.9 mL, per session). That may be justified by the absence of standardized recommendations and by the MPD proximity in our case, increasing the risk of pancreatitis and alcohol-induced duct stricture [2]. EUS-guided radiofrequency ablation is an alternative to EUS-AA with similar results. However, higher costs and lower availability limit its use. Our case supports previous evidence regarding the role of insulinoma EUS-AA in the absence of surgical indication. Small alcohol volumes with repeated sessions may be effective and safer for MPD-adjacent lesions.