Introduction

Obinutuzumab is a humanized glycoengineered type II anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody used in B-cell mediated malignancies. Compared with the well-known rituximab, obinutuzumab mediates an enhanced in-duction of antibody dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity and direct cell death. Consequently, it has been associated with a higher rate of toxicity [1]. Diarrhea is a common side-effect reported in more than 10% of patients [2, 3].

Nevertheless, no clinical, endoscopic, or pathologic features have specifically been reported for obinutuzumab-induced gastrointestinal adverse events. In fact, herein is presented the first case report of an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)-like pancolitis induced by obinutuzumab.

Currently, several drugs, infections, vascular and immune disorders are known to simulate IBD, not only clinically but also histologically. In fact, a holistic and comprehensive clinical assessment with close communication between clinicians and pathologists is crucial for the differential diagnosis between most entities [4].

Drug-induced enterocolitis is usually unspecificand may have pancolonic involvement in 27% of patients [4]. Its mechanisms may range from direct vasoconstriction or dysbiosis to direct cytotoxicity and immune activation. Immune checkpoint inhibitors, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and mycophenolate mofetil are known examples of drugs able to induce enterocolitis. Moreover, some reports have suggested a possible relation between rituximab and de novo or exacerbation of previous IBD and microscopic colitis [4-7].

In a rituximab-associated colitis cohort, gastrointestinal symptoms began on average more than 8 months after drug initiation and included diarrhea (56%), abdominal pain (27%), blood or mucous per rectum (16%), and vomiting (16%). Endoscopic abnormalities were more common in symptomatic patients showing both ulcerative and non-ulcerative features, with pancolonic involvement in 58% of cases. Histological characteristics included mixed inflammatory infiltrate, erosions, ulceration, reactive epithelial changes, and apoptotic bodies [8]. The present case describes a similar obinutuzumab-induced pancolitis with clinical, endoscopic, and histologic features resembling IBD, therefore imposing an exhaustive differential diagnosis.

Case Report

A 47-year-old female with previous medical history of stage IV follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma was treated with R-CHOP chemotherapy (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) followed by rituximab-only maintenance, with prolonged clinical remission. After 7 years of complete remission, the disease relapsed and the patient was submitted to a new induction cycle with obinutuzumab-bendamustine chemotherapy with clinical response and subsequent transition to obinutuzumab-only maintenance.

After 1 year of treatment, the patient presented to a gastro-enterology appointment with a 3-month history of diarrhea, occasionally accompanied by blood and fecal urgency. She denied fever, night sweats, weight loss, abdominal pain, tenesmus, rectal mucus or pus discharge, mucocutaneous or musculoskeletal symptoms. Physical examination including anorectal examination was unremarkable.

Laboratory studies revealed iron-deficiency anemia (hemoglobin level 10.6 g/dL), with microcytosis (VGM 73.8 fL), hypo-chromia (HGM 23.8 pg), and iron deficiency (iron 25 μg/dL, ferritin 44.9 ng/mL, transferrin saturation 8%). Leukocyte and platelet counts were normal. C-reactive protein was 1.69 mg/dL (reference range <0.5 mg/dL), fecal calprotectin was 928 mg/kg (reference range <50 mg/kg), and protein electrophoresis showed hypogammaglobulinemia. No signs of dehydration or malnutrition were found. Stool cultures isolated Campylobacter jejuni. Ova and parasite stool tests were negative. In this context, the patient was prescribed azithromycin 500 mg for 3 days without any symptom improvement.

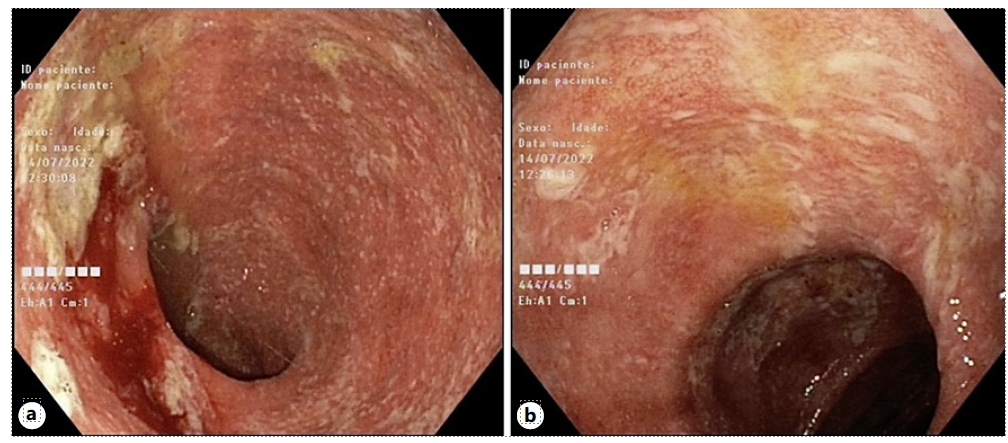

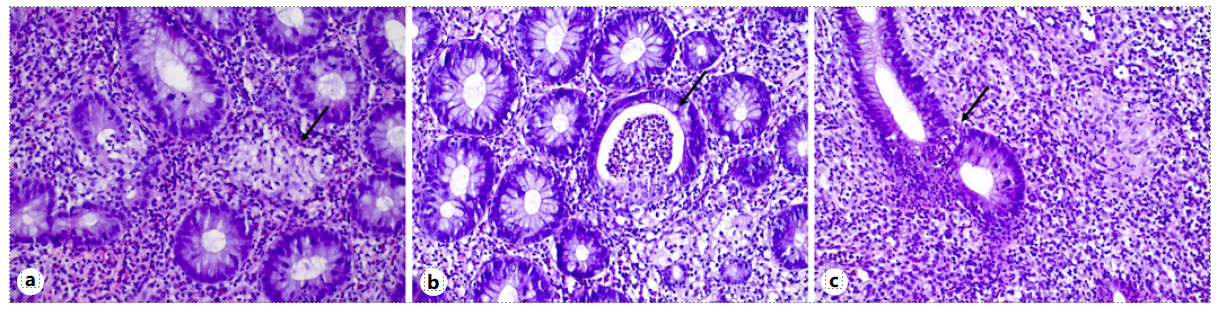

Ileocolonoscopy was performed revealing normal ileal and rectal mucosa. However, the colon mucosa was diffusely erythematous, friable, and superficially ulcerated, with focally adherent exudate (shown in Fig. 1a, b). Colonic biopsies showed a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with focal architectural distortion, cryptitis, crypt abscesses, apoptosis, and epithelioid granulomas (shown in Fig. 2a, c). Acid-fast bacilli smear was negative. Cytomegalovirus was negative by immunohistochemistry.

Considering all clinical, pathological, endoscopic, and histologic findings, we postulated the hypothesis of an obinutuzumab-induced pancolitis. Therefore, in collaboration with the hematooncologist team, the drug was suspended and the patient was kept under close surveillance.

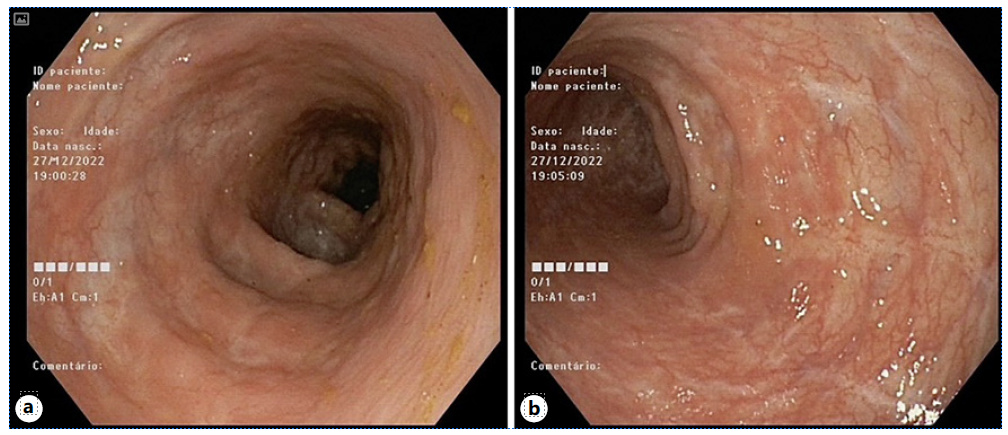

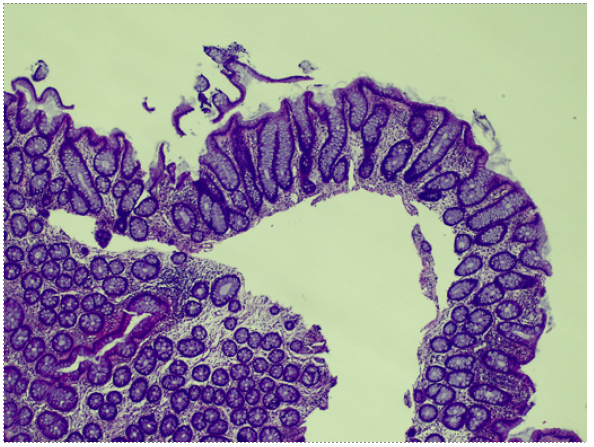

Three months after drug withdrawal, the patient showed complete resolution of symptoms, with 2 formed non-bloody stools per day without fecal urgency. Blood work showed resolution of anemia (Hb 13.1 g/dL) and a sharp decrease of fecal calprotectin (100 mg/kg). Endoscopic and histologic assessment demonstrated mucosal healing (shown in Fig. 3a, b), preserved mucosal architecture, inactive inflammation, and absence of granulomas (shown in Fig. 4a, b).

Fig. 2 a Epithelioid non-necrotizing granuloma delineation (arrow) in lamina propria and in relation to crypts (HE, 20 × 10). b Crypt abscess (arrow) (HE, 20 × 10). c Mixed inflammatory infiltrate, cryptitis, and apoptosis (arrow) (HE, 20 × 10).

Discussion

Throughout the last decades, numerous drugs and chemicals have been recognized as triggers for medication-induced enterocolitis and IBD flares [4]. In this context, a multidisciplinary assessment is crucial to correctly diagnose and manage these patients. In fact, by gathering all clinical, pathological, endoscopic, and histologic findings, the presented clinical case suggested a possible obinutuzumab-induced pancolitis.

The clinical presentation of de novo chronic bloody diarrhea with urgency in a 47-year-old patient could suggest IBD or malignancy [9]. However, the absence of weight loss, fever, abdominal pain, or extraintestinal symptoms did not support these hypotheses.

Regarding laboratory data, iron-deficiency anemia and elevation of fecal calprotectin could have suggested an IBD diagnosis [9]. However, these features are un-specific and the latter one has also been suggested to help predict disease activity and prognosis in drug-related colitis [6]. Endoscopically, the continuous colonic dis-ease resembled extensive ulcerative colitis, except for rectal sparing, which is atypical in a patient not on topical therapy and with no evidence of primary sclerosing cholangitis [9].

Endoscopic biopsies demonstrated both IBD-like features, such as architectural distortion, cryptitis, crypt abscesses, and noncaseating granulomas; and drug-induced features, such as mixed inflammatory infiltrate and apoptotic bodies [4, 5]. Noncaseating granulomas could have suggested a broad spectrum of differential diagnosis, including inflammatory (Crohn’s disease, sarcoidosis), infectious, or drug-induced diseases [4].

Regarding the possibility of de novo IBD, our patient achieved complete clinical, endoscopic, and histological remission with only supportive therapy, which is not typical or suggestive of IBD. However, there might still be a role for drug-induced immune dysregulation and dysbiosis as a trigger for a future IBD diagnosis[10].An IBD misdiagnosis in this context would have implied futile immunosuppression, with short- and long-term potential complications. Additionally, the temporal relation between drug introduction and symptom onset, nearly 1 year of sustained treatment before the beginning of symptoms, and the improvement after drug with-drawal were solid clues pointing to medication-related injury [4].

Moreover, the isolation of C. jejuni from stool culture was considered a confounding factor in this case. The chronic course and the absence of clinical improvement after antibiotics refute the hypothesis that this diagnosis was responsible for the clinical presentation [4]. The authors believe that the bacteria was an innocent by-stander in this case.

Despite the lack of literature, the authors propose the obinutuzumab-induced colitis’ pathogenesis relies on host immune dysregulation, through potent antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, phagocytosis, direct cell death, and dysfunction of B and T-regulatory cells, with consequent dysbiosis and abnormal mucosal barrier [8, 11]. The previous pro-longed exposure to rituximab might have enhanced this pathophysiology through previous cellular immune dysregulation and damage build-up on the colonic mucosa [12].

Additionally, grading severity according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events and managing it similarly to the well-known immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis seems plausible. Our patient presented with grade 2 colitis and medication withdrawal was enough to achieve complete clinical resolution. Nevertheless, in the absence of improvement or if a more serious clinical picture was noted, steroids or biologics might have been required. Resuming obinutuzumab can be considered, although permanent drug discontinuation might be advised [10, 13].

This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first case report of obinutuzumab-induced pancolitis presenting with not only clinical and analytical but also endoscopic and histologic IBD-like features. A thorough differential diagnosis and careful multidisciplinary approach were key to correctly manage this case which had therapeutic and prognostic implications.