Introduction

The measures implemented to combat the COVID-19 pandemic altered the daily lives of all. As societies had to lockdown activities, businesses, and services, and populations were restricted to confinement at home, victims of domestic violence were kept closed in abusive relationships, with increased risk of violence (1, 2).

Domestic violence is a comprehensive term that includes many forms of abuse - physical, psychological, emotional, sexual, and financial - in an intimate or dependent family relationship (3, 4). Historically conceived as a problem of the private domain, domestic violence is currently recognized as a crime and represents a significant public health problem affecting the health and wellbeing of victims, their families, and communities (5-9). It often escalates from threats and verbal assault to life-threatening violence, and victims may suffer different forms of abuse and violence simultaneously (10). Progressive scientific knowledge has shown that domestic violence is a gendered phenomenon, with differences in the magnitude, dynamics, and contexts underpinning domestic violence against women and against men (9). Also, domestic violence is a quite transversal phenomenon across society, affecting all ages and any socioeconomic or cultural group, with complex and deeply entrenched underlying causes, and is often not officially reported (2, 11-14).

The domestic violence phenomenon during the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to follow patterns of previous pandemic events (15), where subsequent social isolation, economic instability, loss of income, and associated stress and family conflicts were strongly connected with increased risk of violence (16-18). But in the current pandemic there is a legal imposition to confinement at home, thus the domestic violence prevalence may be higher than that reported in other catastrophe situations (15, 19, 20). Reports of an increase in domestic violence during the pandemic have been emerging worldwide. Comparing April 2020 with the same period in the previous year, the WHO observed an increase of 60% of emergency calls from women subjected to intimate partner violence in European member states (21). France reported a 30% increase in cases of domestic violence since March (22). Germany and Spain also recorded increases in domestic violence reports and need for emergency shelter (23, 24). In contrast, an 8.6% decrease in complaints of domestic violence was registered in Portugal between January and September 2020 compared to the same period in 2019, and a similar trend was observed in Italy (23, 25).

ocumenting the early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on domestic violence has been challenging due to under-reported cases and under-utilization of social services by victims (20). There is a growing and immediate need to understand the occurrence of domestic violence during this pandemic. Such evidence is key to help develop effective strategies to prevent violence and assist victims. In the face of the lack of evidence on domestic violence in times of pandemic, the NOVA National School of Public Health in collaboration with Ghent University launched the research project “Violence in Intimate Relationships in Times of COVID-19: Gender Inequalities and (New) Contours of Domestic Violence?” This project aimed to better understand the impact of lockdown measures on domestic violence and shed light on help seeking by victims during this crisis. In this study we examine the occurrence of domestic violence, associated factors, and help seeking during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and methods

The project consisted of an online survey conducted between April and October 2020. The survey was disseminated through partner networks, digital social networks, social media, and community institutions working within the scope of violence. After clicking on the link of the survey, potential participants accessed information on the study and the consent form. Only respondents who gave informed consent were able to participate in the survey. The inclusion criteria were being >16 years old and living in Portugal.

Data were collected using a structured, closed-ended questionnaire administered through the Qualtrics software program. Among other questions, participants were asked about their sociodemographic characteristics, victimization in 3 forms of violence (psychological, physical, and sexual), and help seeking. The questionnaire was developed by Ghent University based on the UN-MENAMAIS Study questionnaire (26), drawn on a set of validated instruments (27-30). Minor adaptations were made to the national context in terms of language and the response options to some questions (e.g., level of education). To ensure cross-country comparability, all proposed changes were agreed by both country research teams. The questionnaire was pretested among a convenience sample of individuals who met the inclusion criteria to ensure comprehensibility and solve operational errors.

Descriptive analysis was performed to analyze sociodemographic characteristics and domestic violence outcomes. Bivariate associations between sociodemographics and reported domestic violence, including psychological, physical, and sexual violence, were assessed using χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests when appropriate. Bivariate logistic regression analyses stratified by sex were performed to estimate the crude odds ratios (OR) and 95% CIs of factors associated with reported domestic violence. A significance level <0.05 was used. Data analysis was performed using IBM-SPSS Statistics version 26.

Results

In total, 1,062 participants responded the online survey. Their characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Overall, 146 participants (13.7%) reported having suffered domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 1). There was a trend of lower age associated with more domestic violence being reported. Also, a higher proportion of participants who perceived difficulties in making ends meet during the pandemic reported domestic violence (17.7%). Differences in reported domestic violence between women and men and across educational levels were not statistically significant.

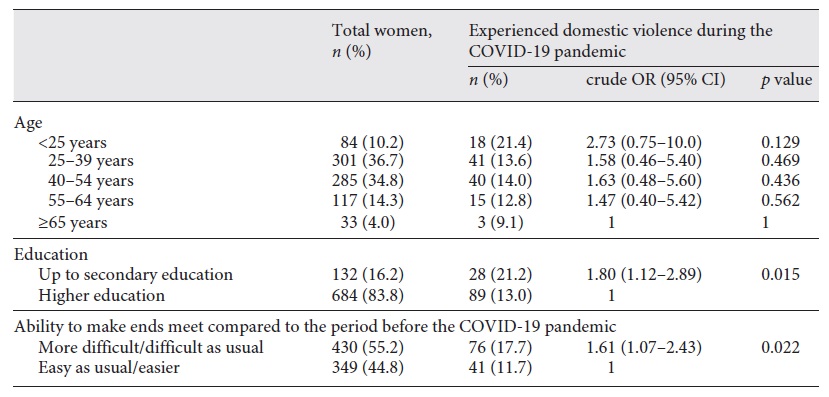

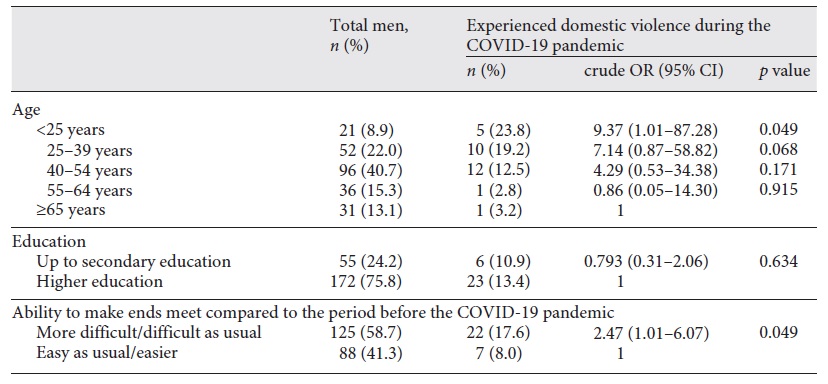

Bivariate logistic regression analyses stratified by sex showed that for women reported domestic violence was more likely among those with up to secondary education compared to higher education (Table 2). In both sexes, reported domestic violence remained more likely among those reporting difficulties to make ends meet during the pandemic and was also higher among those of younger age (although not statistically significant among women; Tables 2, 3).

Table 2 Reported experience of domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic and associated factors among women (n = 826)

Table 3 Reported experience of domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic and associated factors among men (n = 236)

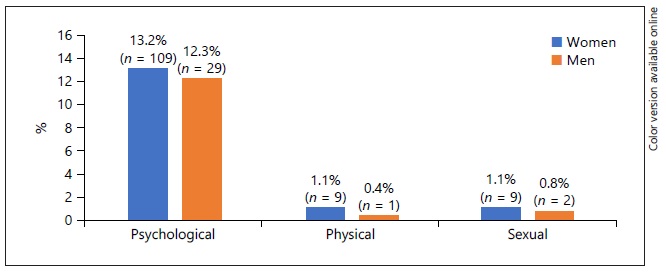

The perpetrator of the abuse was mostly a partner/ex-partner (47.3%, n = 69), but for some victims it was a parent/stepparent (17.8%, n = 26), a child/stepchild (8.9%, n = 13), a sibling/stepsibling (1.4%, n = 2), or someone else the victim was currently living with (2.7%, n = 4); 32 participants (21.9%) did not report who the perpetrator was. Regarding the form of violence, a significant proportion of participants reported psychological (13.0%, n = 138), sexual (1.0%, n = 11), and physical violence (0.9%, n = 10) during the pandemic. A total of 11 participants suffered concurrent forms of violence: psychological and physical (4 women and 1 man), psychological and sexual (2 women and 2 men), and psychological, physical, and sexual (2 women).

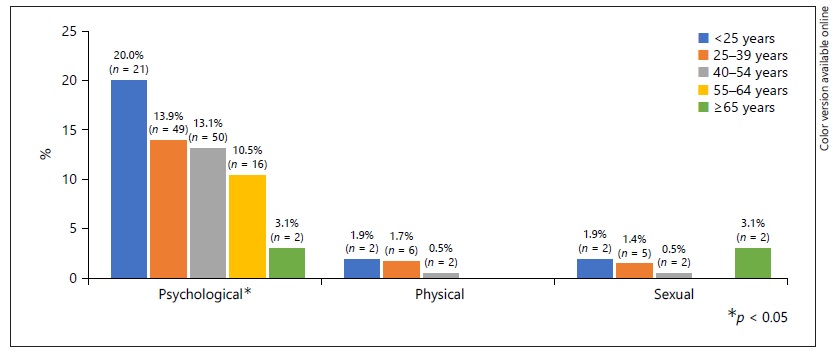

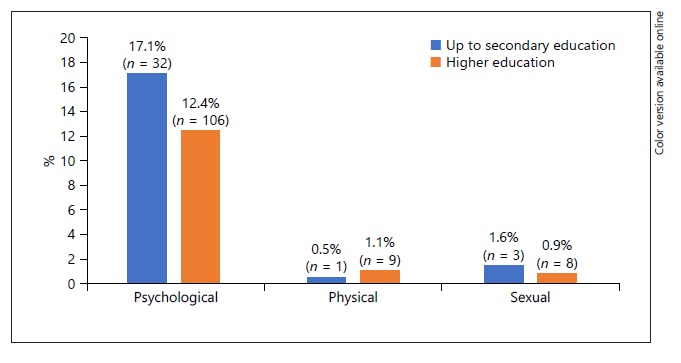

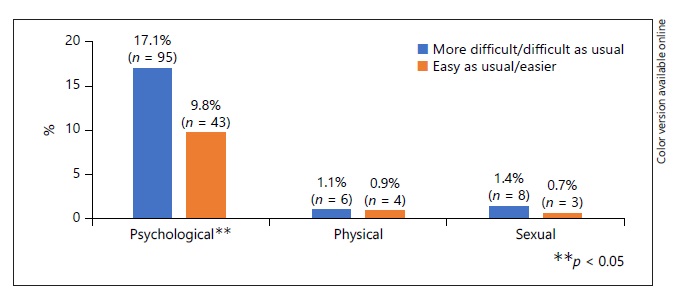

Women were more exposed to any form of violence than men, though differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 1). Younger participants (<25 years old) reported the highest proportion of psychological and physical violence (Fig. 2). The older the participants, the less the reported psychological abuse. Nevertheless, among the elders (≥65 years old), a high proportion reported sexual violence (3.1%). Participants with up to secondary education reported particularly high rates of psychological violence during the pandemic (17.1%; Fig. 3). Also, 1.6% of those with up to secondary education reported sexual abuse. Among participants with higher education, a significant proportion reported psychological and physical violence. Participants who perceived difficulties in making ends meet during the pandemic were more prone to suffer psychological violence and reported high rates of sexual and physical violence (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Reported psychological, physical, and sexual violence by perceived ability to make ends meet compared to the period before COVID-19.

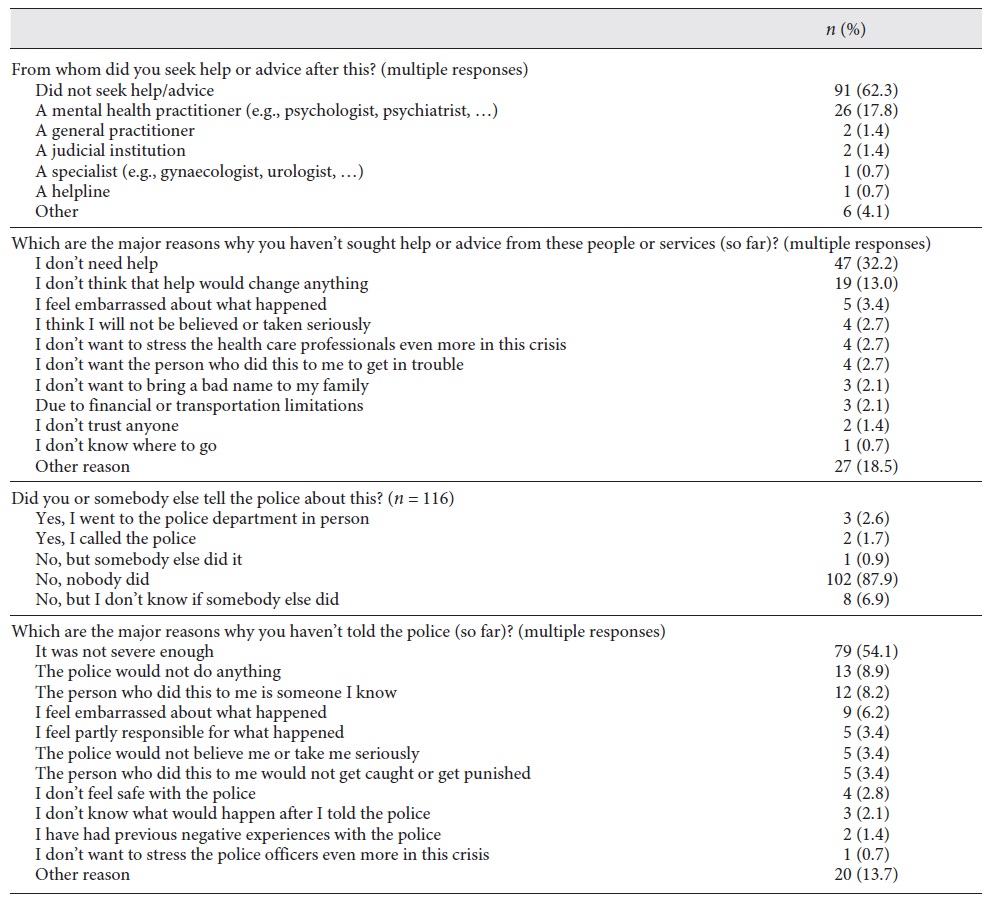

Table 4 describes help seeking during the COVID-19 pandemic by the participants who experienced any form of violence (n = 146). Most of the victims did not seek help (62.3%), and the main reasons were because they considered it was not needed (32.2%) and that help would not change anything (13.0%). Other reasons included feeling embarrassed about what had happened (3.4%), thinking they would not be believed or taken seriously (2.7%), not wanting to stress the health care professionals even more in this crisis (2.7%), not wanting the perpetrator to get in trouble (2.7%), not wanting to bring a bad name to their own family (2.1%), and financial or transportation limitations (2.1%). Around 19% of the victims reported other reasons, although no specification was made.

Overall, 38 participants reported having sought professional help, mainly from mental health professionals (17.8%), but also from a general practitioner (1.4%) and a judicial institution (1.4%), while 17 participants did not report if they had sought help. Only 4.3% of the victims sought police help - 2.6% went personally to the police department and 1.7% called the police. Around 88% stated they did not present any complaint to the police, and 6.9% did not complain but were unaware whether someone did. The main reason keeping victims from coming forward to form a complaint was not considering the abuse severe (54.1%). Some victims also pointed out they believed the police would not do anything (8.9%), that the person who committed the abuse was someone they knew (8.2%), and feeling embarrassed about what had happened (6.2%).

Discussion

This study provides evidence of domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic, in line with the literature suggesting a high occurrence of violence in times of crisis or disasters (15, 24). Domestic violence has strong implications for the health of the victims, including adverse mental health outcomes such as mood disorders and anxiety (31). Importantly, in our study most of the victims did not officially report the abuse or seek help.

The findings indicate that domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic is transversal to both sexes and across different age groups. The high rates of reported domestic violence found against women (either psychological, physical, or sexual) extends the existing literature on the nature of this phenomenon, which is generally described as a gender-based crime where women are mostly victims (2, 14). Among female participants, domestic violence affected all age groups but varied with educational level, affecting disproportionately those with secondary education compared to higher education.

A significant proportion of victimized men, especially of psychological abuse, was also found in our study, which deserves attention. In this group domestic violence was independent of education but was significantly higher among younger individuals. While the concept of masculinity has been used to understand embodied practices and structural reinforcement of gender-based violence against women within patriarchal systems of power, little research has explored male victims’ vulnerability and help seeking (32-34).

The findings indicate that the younger the participants, the more the reported domestic violence, in line with the literature (35). In addition, a relevant finding is that a particularly high proportion of elder participants reported sexual violence. Globally, there are limited official estimates of sexual abuse of older persons. There may be a risk that sexual abuse against this group is overlooked since, due to ageism, they may be seen as asexual, and thus sexual abuse may be considered unlikely to occur (36).

An association was found between perceived financial difficulties triggered by economic crisis during the pandemic and domestic violence, either among women or men. Research on the initial effects of the pandemic shows an aggravation of social inequalities, with increasing unemployment and loss of income that, in addition to isolation during the confinement of lockdown, have been drivers of domestic violence (37, 38).

In our study, the majority of the victims did not seek professional help or present a complaint to police authorities. Some of the most common reasons reported by participants for not seeking help are consistent with the literature, including playing down the significance of the abuse, feelings of shame and embarrassment, and sense of lack of support and distrust from the services, among others (38). Seeking help from health services, community associations, or the police may have also been reduced in the face of the restrictive measures to combat the pandemic that impacted the office hours of many institutions.

The limitations of this study must be acknowledged. Due to the sampling procedure, results may not reflect the situation of the population in general. Volunteer bias cannot be excluded and, being an online study, it might have included particularly those with digital literacy. Social desirability bias potentially led to under-reporting of experiences of violence. Nevertheless, the anonymous online nature of this survey might have contributed to minimizing those effects. Overall, the burden of domestic violence could be under-represented. Given the relatively low numbers, which hindered further complex analyses, results must be treated with caution. The wide dissemination of the survey allowed a sample of 1,062 participants to be reached, with a high participation of respondents with higher education. Although the study design led to the inclusion of mainly highly educated groups, this can be considered a strength of the study as these groups are not frequently included in research on domestic violence (6, 35).

In conclusion, although progress has been made in efforts to prevent psychological, physical, and sexual violence, this study shows that there is a need for investment in specific support systems for victims of domestic violence to be applied to pandemic contexts, especially targeting those in more vulnerable situations, potentially underserved, and who do not access online platforms or have limited digital literacy. To our knowledge this is one of the largest community-based surveys conducted so far on domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic in Portugal. It provides insights to inform public policies regarding management mechanisms of domestic violence while examining the vulnerabilities of the system, which will be valuable should lockdown measures be repeated or re-instituted in the future.

Statement of ethics

The study was approved by the Ethics Commission of the NOVA National School of Public Health (ref. CE/ENSP/ CREE/1/2020). The research conforms with the guidelines for hu- man studies and was conducted ethically in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Anonymity of participants and confidentiality of data were guaranteed. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Funding sources

This study was co-financed by the Foundation for Science and Technology, under the financing program “GENDER RESEARCH for COVID-19,” with the following project partners: NOVA Na- tional School of Public Health (ENSP-NOVA), NOVA School of Social Sciences and Humanities (NOVA FCSH), University Insti- tute of Maia (ISMAI), and School of Criminology, Faculty of Law, University of Porto.

Author contributions

A.E.G., A.R.P., I.K., and S.D.: concept and design. A.E.G., A.R.P., M.J.L.d.C., A.E.G., V.D., J.Q., A.M., and S.D.: acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data. A.E.G., A.R.P., and S.D.: draft- ing of the manuscript. A.E.G., A.R.P., A.M., M.J.L.d.C., A.E.G., V.D., J.Q., I.K., and S.D.: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. S.D. and A.E.G.: supervision.