Introduction

Food insecurity (FI), which can be defined “as limited or uncertain access to sufficient, nutritious food for an active, healthy life” 1, is a worldwide public health problem. Traditionally present in low- and middle-income countries, FI is also of concern among high-income countries 2,3. FI has been shown to lead to adverse health outcomes 4-6, such as mental health issues 7-9, poor diet quality, and non-communicable diseases, such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases 10.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has had an unprecedented impact 11 since approximately mid-March 2020, not only on the population’s health, but also on social systems worldwide 12. The inherent social and economic response to the COVID-19 pandemic has shown a negative influence on people’s working status, causing job losses and lay-offs, which may have decreased families’ incomes 13,14. Taken together, these changes may lead individuals and their families to become vulnerable to FI, increasing its prevalence and related health discrepancies, particularly among already at-risk population groups. Unfortunately, the aforementioned unprecedented nature of this pandemic seems to have created a window of opportunity for new households to be affected by FI 15.

In the USA 13,16,17, unprecedented levels of FI have been reported. Over the past 5 years, the US Department of Agriculture estimates of FI has been between 11 and 12% 16, while during the pandemic it more than tripled to 38% 17. In Portugal, before the pandemic, the results from a large national study, National Food and Physical Activity Survey (IAN-AF), showed that from 2015 to 2016, 10.1% of families in Portugal experienced FI 18. From these study, it was also clear that families with monthly incomes below the national minimum wage, and families with low education levels, have significantly more FI 18. Moreover, and considering data collected after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, and in the middle of a period of universal confinement, the ReactCOVID study, conducted by the Directorate-General for Health throughout the national territory, showed a much higher prevalence of FI - 32.3% 19.

Considering this, and in light of Goal 2 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) - “End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture” 20 - it is of the utmost importance to explore the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the population’s food security status. Therefore, this study aimed to characterize the scenario of FI in a sample of Portuguese residents during the COVID-19 pandemic and to explore its related sociodemographic characteristics.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

A virtual cross-sectional snowball sampling survey was carried out. Being a Portuguese resident with 18 years of age or older were the inclusion criteria to participate in the study. The questionnaire was prepared online and, first, it was disseminated through social networking channels, namely Facebook®, Instagram®, LinkedIn®, WhatsApp® groups, and Twitter®. Secondly, the questionnaire was disseminated by using the personal mailing lists of the researchers involved.

Recruitment took place between November 2020 and February 2021 and included 929 participants. Of those, 882 participants were included in the present study, as they had complete data on food security status. Full and detailed information on the study methodology can be found elsewhere 21.

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Data on sex, age, and education were collected. Education was classified as ≤12 completed schooling years, bachelor’s degree, and master’s degree or higher. For working status, a composed variable was created based on information on working status in January 2020 and on working status during the COVID-19 pandemic, by classifying individuals as: “remained employed,” “became unemployed,” “remained unemployed,” and “other” (including students, housewives, and retired participants).

Information on marital status was also collected, and participants were classified as married or in a civil partnership or single. Household size was accounted for the number of individuals living in the same house, and was classified into three categories: “1 person,” “2 persons,” and “≥3 persons.” Household income perception was as classified as “insufficient,” “need to be careful about expenses,” “enough to meet needs,” or “comfortable.” Participants were also asked about their parish of residency, which was categorized into NUTS II categories: North, Center, Alentejo, Lisbon Metropolitan Area, Algarve, and Islands (Azores and Madeira) 22.

Food security status was assessed using the US Household Food Security Survey Module: Six-Item Short Form 23. Participants were asked about the food eaten in their households and whether they could afford the food they need, related to the previous 12 months. The sum of affirmative responses to the six items in the module corresponds to the household’s raw score on the scale. The individuals’ household food security status was assigned as follows: “food secure” if the number of affirmative responses was equal to or less than one, “low food secure” if between two and four affirmative answers, or “very low food secure” if the number of affirmative responses was five or six.

To complement, an open-ended question was added for participants to comment on their experiences and perceptions of food security status changes since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the scale used for food security status assessment not being fully validated for the Portuguese population, previous studies among Portuguese individuals have reported good internal consistency 24,25.

Statistical Analysis

The sample characteristics were reported as counts and percentages for categorical variables, and as the mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables. χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests were employed to compare categorical variables, as appropriate. For continuous variables, Student’s t-test or analysis of variance were used.

Logistic regression models were performed, and the odds ratio (OR) and the respective 95% confidence intervals (CI) were computed. For these analyses, food security status as food security and FI (including low and very low food security) was used. The final model was adjusted for education, working status during the COVID-19 pandemic, and household income perception.

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) 26. A significance level of 5% was used.

Results

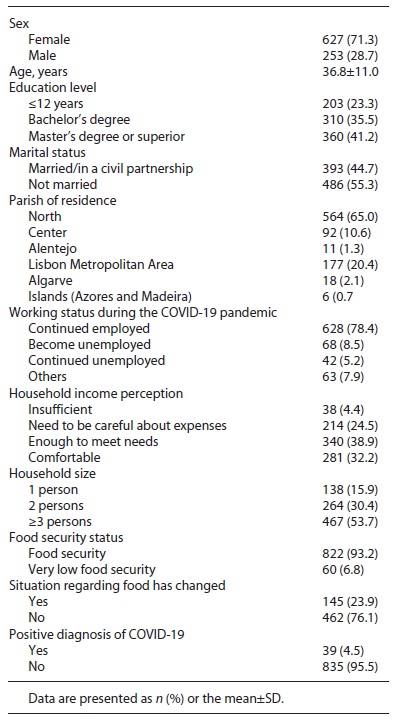

Most participants were women (71.3%), 76.7% had a university degree, 44.7% were married, and 65% lived in the country's northern region. In addition, participants had a mean age of 36.8 (SD 10.9), and most were employed and had continued to be employed since the pandemic started (78.4%). Concerning the food security status of the households, 6.8% were described as being food insecure: 5.0 and 1.8% reported low and very low food security status, respectively (Table 1).

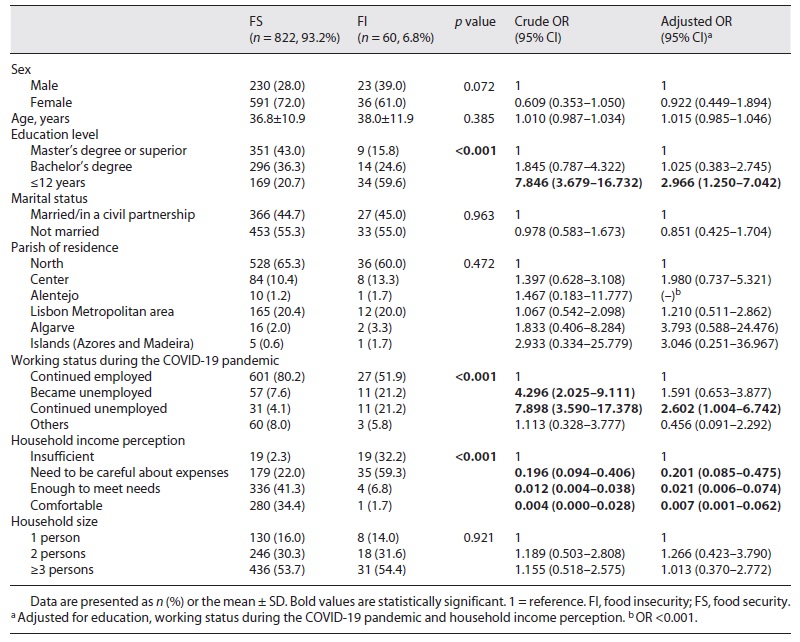

Individuals belonging to a food-insecure household were more often women (p = 0.072), with lower education level (≤12 years of schooling; p < 0.001) and had a slightly higher mean age (p = 0.385), compared with food-secure households. Also, participants from food-insecure households were more likely to remain unemployed (p < 0.001) and to refer to the need to be careful about expenses (p < 0.001) compared with individuals from food-secure households (Table 2).

Individuals with ≤12 years of education (OR 7.846; 95% CI 3.679-16.732), unemployed before and since the beginning of the pandemic (OR 7.898; 95% CI 3.590-17.378), and those who became unemployed (OR 4.296; 95% CI 2.025-9.111) were significantly more likely to experience FI (Table 2). Moreover, participants reporting the need to be careful about expenses (OR 0.196; 95% CI 0.094-0.406) were less prone to belong to a food-insecure household (Table 2).

Furthermore, independent of working status during the COVID-19 pandemic and household income perception, those with lower educational levels have almost three times greater odds of being in the FI category (OR 2.966; 95% CI 1.250-7.042), compared to those in the master’s degree or superior educational level group. Also, participants who were unemployed before and since the beginning of the pandemic (OR 2.602; 95% CI 1.004-6.742) and those reporting the need to be careful about expenses (OR 0.201; 95% CI 0.085-0.475) remained more likely to be food insecure (Table 2).

Discussion

In a sample of Portugal’s residents, a prevalence of FI of 6.8% was found. Characteristics such as being less educated (≤12 years of schooling), unemployed, and having a perception of insufficient household income were observed to be associated with greater odds of being in an FI household in Portugal. Additionally, when asked about their perception of household income, we observed that those perceiving the household income as “comfortable,” “enough to meet needs,” and “need to be careful about expenses” were negatively associated with FI, compared with those who categorized their income as “insufficient.”

The prevalence of FI was lower than previously described in Portuguese households before the COVID-19 pandemic. In the IAN-AF Survey 2015-2016, a prevalence of FI of 10.1%, was reported 18. Also, Maia et al. 24, found a higher prevalence estimate of FI in middle- and older-aged urban adults in Portugal (16.6%) at the time of the 2008 economic crisis recovery.

More recently and during the COVID-19 pandemic, Madeira (an island belonging to Portugal), estimated that 33.6% of adults and their families were at risk of FI 27. In comparison to our sample, this group of participants was older (55.1% ≥60 years), more often reported being in a difficult or very difficult financial situation (55.1%), had a low educational level (48.3%), and 38.1% were unemployed.

Furthermore, after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, and amid general lockdown, the ReactCOVID study reported a prevalence of FI, weighted for the Portuguese population, of 32.3% 19. The prevalence found in these studies is much higher when compared to ours. However, the discrepancy in the results could be justified by the use of different scales, limiting comparisons.

Education is a crucial social determinant of health 28. Previous studies have found that a low educational level is associated with FI 29,30. Concerning household income perception, previous evidence, including Portuguese studies 24,31,32, reported that having a low or insufficient household income is positively associated with FI. This corroborates our findings as the individuals who had the perception of a comfortable household income were less likely to belong to an FI household.

Unemployed individuals showed a 2.6 greater odds of belonging to an FI household. It has been reported that being employed is consistently associated with lower odds of FI 33,34. Thus, this not only supports our findings, but previous research in Portugal has also stated that unemployed individuals were more likely to be food insecure 30.

Some limitations of this study should be mentioned. Given the limited resources available and time sensitivity of the COVID-19 outbreak, we adopted the snowball sampling strategy. The strategy was not based on a random selection of the sample, and the included sample may not reflect the actual pattern of the general population. Thus, the possibility of selection bias cannot be discarded. Nevertheless, the snowball sampling method is still very valuable and convenient nowadays - such as during the COVID-19 pandemic - in overcoming constraints due to the governments’ social physical distance measures. Also, the current data were collected through an online survey. Thus, there may be an underrepresentation of some groups of the population, such as those who were also more likely to experience FI, which cannot be discarded 35. Moreover, all data collected in the survey were self-reported, which may be subject to social desirability bias. Despite this possibility of social desirability bias, the fact that the survey was completed online and no personal information allowed for the identification of the participants could diminish this concern. Also, because this study has a cross-sectional design, inferences about causality cannot be made. Furthermore, despite the scale used for the food security status assessment not being fully validated for Portugal, previous Portuguese studies have reported good internal consistency 24,25.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had wide-ranging impacts on the lives of Portuguese residents, including increased health risks and disruptions to employment, schooling, and daily routines 36. This study relies on data collected over 3 months when many lockdown measures were applied across the entire country and aimed to examine the association between household FI and sociodemographic characteristics.

As for the strengths of this study, it can be pointed out that our study provides timely and important insights on the burden of FI during the pandemic. Indeed, before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the SDGs highlighted the relevance of monitoring and reducing FI 37. COVID-19 posed the threat of aggravation of FI and alterations of the SDGs goals, namely through food supply chain disruptions that create higher food prices and food shortage, especially in countries already affected by high levels of FI 38. Additionally, school children faced the lack of proper meals with the interruption of classes 39. Our study provides a relevant contribution regarding the scenario of FI and the identification of its sociodemographic associates during the COVID-19 pandemic, even using a younger and highly educated sample of adults.

Conclusion

Although the FI prevalence found was lower than those previously described in Portuguese households, this research concluded that FI is a critical aspect that affected the social and environmental status before the pandemic. Individuals with a lower educational level, who were unemployed before the pandemic, and those who became unemployed after the pandemic started, were significantly more prone to experience FI. The findings of this study also highlight the relevance of the development of public health policies to deal with this issue to promote food security, which is of the utmost relevance for the accomplishment of Goal 2 of the SDGs.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the participants who answered the questionnaire. This research initiative would not be possible without your participation.

Statement of Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Public Health of the University of Porto (CE20166). By accessing the questionnaire through the link, all participants were asked to give their informed consent according to the Ethical Principles for Medical Research involving human subjects expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki and the current national legislation. The questionnaire was confidential, and no data allowing personal identification were collected.

Funding

This work was financed by Portuguese Funds through FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., under the projects UIDB/04750/2020 and LA/P/0064/2020. This study was also supported by the PhD Grant 2020.09390.BD of Ana Aguiar, co-funded by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) and the Fundo Social Europeu (FSE) Program. Isabel Maia holds a PhD Grant (Ref. SFRH/BD/117371/2016), co-funded by the FCT and the POCH/FSE Program. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.