Introduction

Supported accommodations (SAs) are specialised mental health services that provide housing and psychosocial rehabilitation for people with serious mental disorders and complex needs 1. Despite their wide variation worldwide, overall, they focus on the development of living skills to promote greater autonomy and social inclusion and facilitate recovery 1,2.

Globally, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected mental health services, with many closing or decreasing activities 3-5. In addition, it has been associated with a negative impact on the well-being of healthcare workers (HCWs) 6-9. People with a previous history of mental disorders have also been considered at risk, but findings have been contradicting 10,11.

Very few studies have been conducted on the impact of COVID-19 on SAs despite their specificity and their importance to a community mental health system 12-19. The few studies conducted in this setting have been mostly qualitative and included limited numbers of SAs and different rehabilitation services besides SAs 12,14-19. In addition, only a few studied the factors associated with outcomes in residents and the staff 12,13. Nevertheless, these studies pointed to several challenges in the provision of care in SAs, with many having to cancel daily activities and decreasing contact with residents 14-18. Data regarding the impact on residents have been contradictory 12,13,15,17-19. While some reported that residents presented none to mild symptoms of anxiety, depression, and stress, others reported anxiety, distress, sleep impairment, or exacerbation of pre-existing mental disorders 12,13,15,17-19. Regarding SAs’ staff, the limited existing studies have pointed to a negative impact of the pandemic on their well-being 14,16,18.

Given the specificity of SAs, it seems fundamental to better understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on these services. In particular, it is important to understand what changes occurred in SAs, the impact on residents and the staff, and factors associated with worse outcomes, using a quantitative methodology and including SAs only.

This study is the first part of a larger one on the impact of COVID-19 on SAs in Portugal. Here, we aimed to quantitatively analyse how the staff of different SAs assessed work challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic, the impact of the pandemic on the staff, and how they perceived the impact on residents. We also aimed to analyse associations between the staff’s assessments of work challenges and their sociodemographic characteristics, and also between the staff’s assessments of work challenges and the impact of the pandemic on themselves.

Methods

Study Design and Selection of Participants

A cross-sectional study was conducted on the staff of SAs for people with serious mental disorders in Portugal. Nationally, SAs typically vary according to the support provided, ranging from maximum support, where residents present high disability levels and in-person support is provided 24 h/day, to minimum support, where residents present low disability levels and in-person support is usually provided a few hours per week.

As a first step, to identify the existing SAs nationwide, contacts were made with the Ministry of Health, religious orders, public psychiatric hospitals, and a governmental website on social organisations was consulted 20. In total, 60 SAs were identified, and an email inviting them to participate in the study was sent to each. Of these, 42 SAs agreed to participate (70% response rate). Upon acceptance, a second email was sent to the managers of each SA with an online link to a questionnaire which was asked to be filled out by all the staff of the SAs, including the manager. A letter explaining the study and encouraging staff participation was also included and asked to be distributed among all professionals. Data were collected between January and July 2022. The final analysable sample was composed of professionals of 32 SAs from the 42 that initially accepted to participate (i.e., a 53.3% adherence considering the 60 nationally identified SAs).

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by an Ethics Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from every participant, and data confidentiality was guaranteed.

Identification and Measurement of Variables

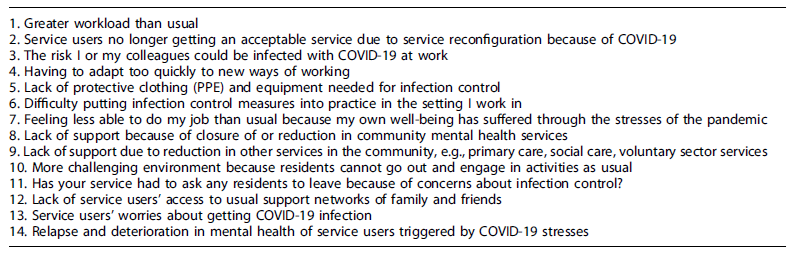

A questionnaire based on the instrument “COVID-19: what’s happening in mental health care?” developed by Johnson et al. 14 was used. The original questionnaire was developed to measure the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health care according to the staff of different mental health settings across the UK. An extended group of clinicians, researchers, and people with lived experience was involved, with additional input from experts in specific mental healthcare fields. Afterwards, it was pilot tested for length, acceptability, and relevance. The first section of the questionnaire was to be answered by the staff from all mental health services, which was then followed by sections aimed at the staff from specific settings, including SAs. In both sections, the staff were asked to rate the relevance or the presence of several work challenges during the pandemic, including problems faced by residents from the staff’s perspective. For example, for certain work challenges such as “greater workload than usual,” the staff were asked to rate its relevance during the pandemic as “not relevant,” “slightly relevant,” “moderately relevant,” “very relevant,” or “extremely relevant.” For items such as “has your service had to ask any residents to leave because of concerns about infection control?,” ratings included “yes” or “no.” Possible work challenges during the pandemic included, for example, greater workload, the risk of being infected at work, staff feeling less able to do the job than usual because their own well-being had suffered through the stresses of the pandemic, lack of access of residents to usual mental health services, and relapse and deterioration in the mental health of residents triggered by COVID-19 stresses. The questionnaire aimed to provide an overview of the impact of the pandemic, and thus, no score is yielded. For the current study, and due to the instrument’s length, 14 items of the original instrument were selected upon review of the most significant literature on the topic and consensus between the research team (see Table 1). A forward translation to Portuguese was done independently by two individuals, after which both versions were compared, and a preliminary version of the instrument was jointly decided. A back-translation of this initial version was then conducted, and items that did not retain their original meaning were re-translated and back-translated again. This questionnaire was then administered online to the staff of SAs.

Work Challenges

For this study, the work challenges included from the original instrument addressed workload (item 1), service acceptability (item 2), worries regarding infection (item 3 and item 13), work adaptations (item 4), protective clothing (item 5), infection control (item 6), support from community services (item 8 and item 9), challenging environment (item 10), and access of residents to social networks (item 12) (see Table 1). Due to the small sample size and its relatedness, items addressing protective clothing and infection control were transformed into one variable, as well as items addressing support from community mental health services and other services in the community. To study the association between work challenges and the impact on the staff, all items, except item 11, were included.

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Staff and Residents

Items “feeling less able to do my job than usual because my own well-being has suffered through the stresses of the pandemic” (item 7) and “relapse and deterioration in residents’ mental health triggered by COVID-19 stresses” (item 14) were used to assess the impact of COVID-19 on the staff and the perceived impact of COVID-19 on the residents, respectively (see Table 1).

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Staff

Sociodemographic characteristics were assessed using adapted questions from the original instrument and included gender (male/female), age (under 25/25-34/35-44/45-54/55-64/65 or over), profession (psychologist/nurse/occupational therapist/social worker/other), having a leadership role (yes/no), years working in mental health (years), caring for children under 18 (yes/no), caring for elderly or disabled relatives or friends (yes/no), the staff’s SA type of support (minimum/autonomy training SAs/moderate/maximum), and the staff’s SA location (Lisbon Metropolitan Area LMA/North/Centre/South/Insular Region). Age was categorised into “less than 45” and “45 or over” since worse COVID-19 outcomes were associated with increasing age; profession into “technical team” (which included psychologists, nurses, occupational therapists, and social workers) and “support workers,” given their different main tasks; years working in mental health into “less than 3 years” and “3 years or over,” to distinguish between those working in mental health since the pandemic and those who had been working before; staff’s SA type of support into “minimum” (which included minimum support SAs) and “moderate to maximum” (which included “autonomy training,” moderate, and maximum support SAs), to distinguish between those which usually provide more periodic support and those providing daily support; and staff’s SA location into “LMA” and “outside LMA,” due to the predominance of SAs in the LMA.

Statistical Analysis

For all analyses, we categorised answers “not relevant,” “slightly relevant,” and “moderately relevant” into “not relevant to moderately relevant,” and answers “very relevant” and “extremely relevant” into “very to extremely relevant.” This was due to the sample size obtained on some of the responses which would hinder the analysis as well as to clearly distinguish participants who felt at least very relevant work challenges from those who did not. Absolute and relative frequencies were used to describe categorical data. Bivariate and multivariable analyses, consisting of multilevel/hierarchical logistic regression models, were conducted to assess associations while considering possible SAs effects. To study the association between work challenges and the staff’s sociodemographic characteristics, impact on the staff, and the staff’s perception of the impact on residents, sociodemographic characteristics were considered as independent variables, while work challenges, impact on the staff, and the staff’s perception of the impact on residents were considered the dependent variables. To study the association between work challenges and the impact on the staff, work challenges were considered as independent variables while the impact on the staff was considered the dependent variable. As a first step, all variables whose association with the outcome yielded a correspondent p < 0.25 were included in multivariable analyses 21. Sociodemographic characteristics associated with either dependent or independent variables were considered potential confounders in the multivariable analyses between work challenges and the impact of the pandemic on the staff. Estimated crude (OR) and adjusted odds ratios, their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and p values are presented, as well as intra-class correlation values. VIF analyses were used to investigate possible multicollinearity among the explanatory variables, and model assessment and model fit were performed. RStudio (version 1.2.5033) was used for statistical analysis, including DescTools and lme4 R packages 22.

Results

Staff’s Sociodemographic Characteristics

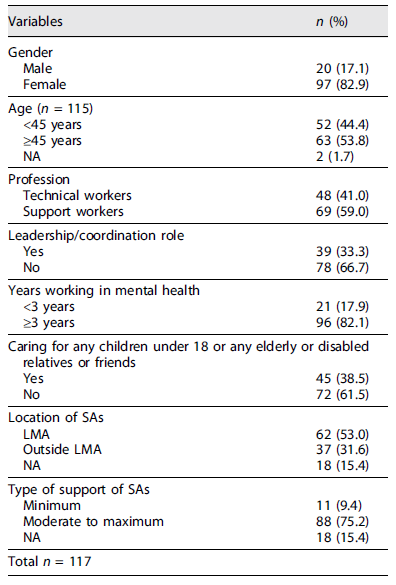

In total, 117 participants from 32 SAs have responded. The staff’s sociodemographic characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Work Challenges during COVID-19 and the Impact of the Pandemic on the Staff and Perceived Impact on the Residents

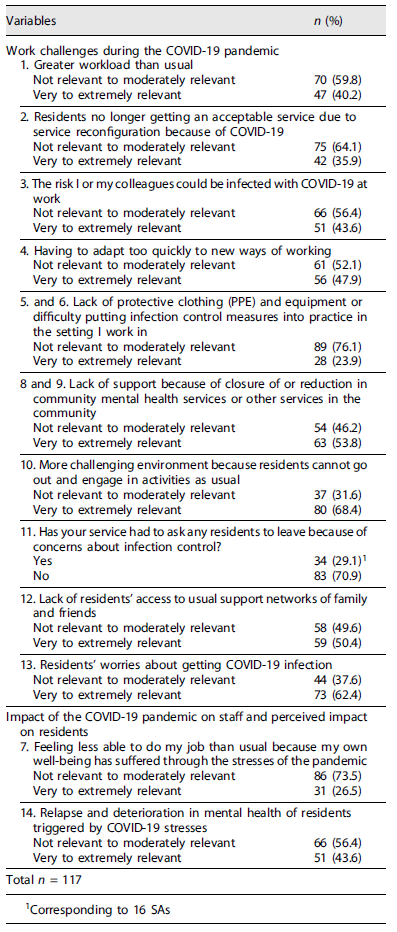

The most reported challenges were (see Table 3) a challenging environment (68.4%), residents’ worries about COVID-19 infection (62.4%), lack of support from community services (53.8%), and lack of residents’ access to usual social support networks (50.4%). Regarding the impact of the pandemic on the staff and the residents, 26.5% of the staff reported feeling less able to do their job than usual because their well-being had suffered, and 43.6% reported relapse and deterioration in the mental health of residents.

Relationship between the Staff’s Sociodemographic Characteristics and Work Challenges, the Impact of the Pandemic on the Staff, and the Perceived Impact on the Residents

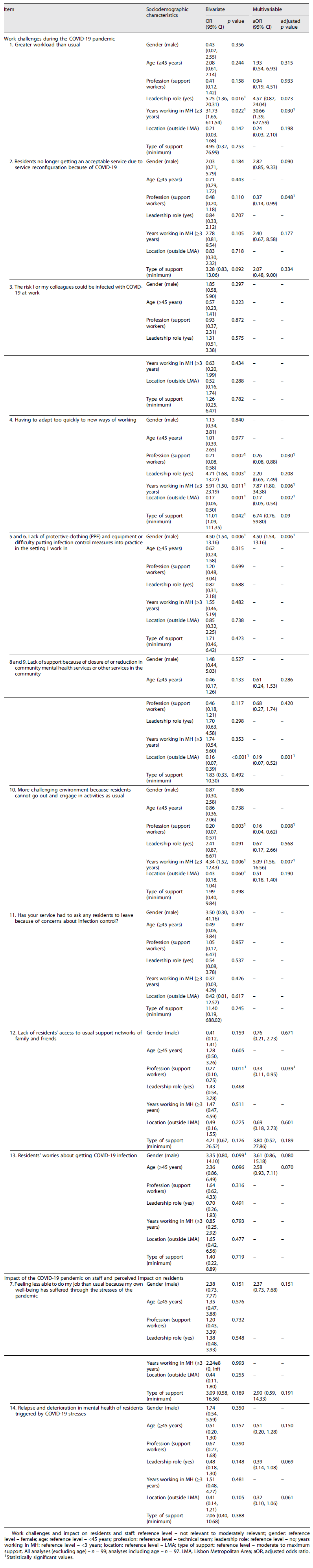

Compared to technical workers, support workers had a decrease in the odds of reporting residents no longer getting an acceptable service, having to adapt too quickly to new ways of working, a challenging environment, and a lack of residents’ access to usual support networks (see Table 4). Staff working in mental health for 3 years or longer had greater odds of reporting having to adapt too quickly to new ways of working and a challenging environment. Staff from SAs located outside LMA had a decrease in the odds of reporting having to adapt too quickly to new ways of working and a lack of support from community services. Male staff had greater odds of reporting lack of protective clothing (PPE) and equipment or difficulty putting infection control measures into practice.

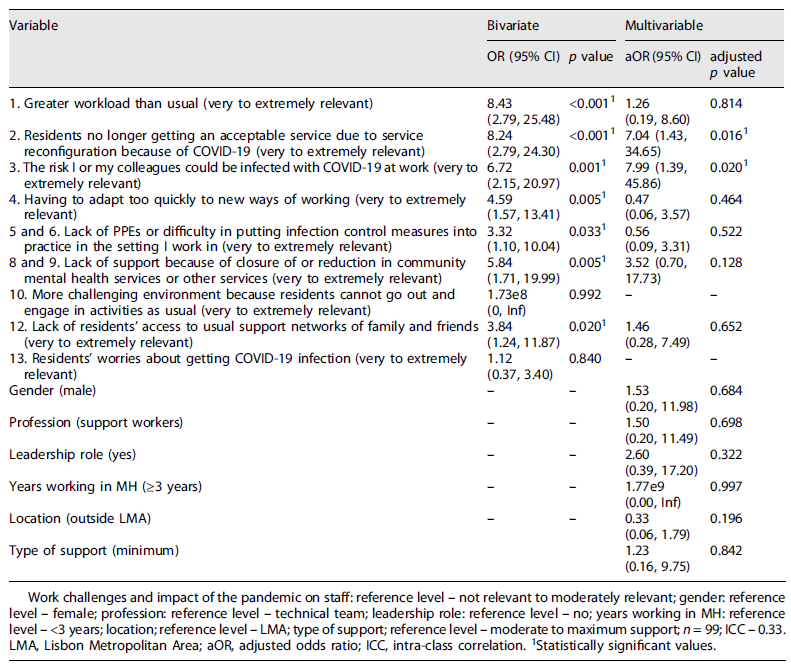

Relationship between Work Challenges and the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Staff

Residents no longer getting an acceptable service (OR = 7.04, 95% CI (1.43, 34.65), p = 0.016) and the risk of being infected at work (OR = 7.99, 95% CI 1.39, 45.86, p = 0.020) were significantly associated with the staff feeling less able to do their job than usual because their well-being had suffered (see Table 5).

Discussion

SAs’ staff reported several work challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic, which were differently experienced across the professionals. Reporting that residents were no longer getting an acceptable service and the risk of being infected at work were associated with a negative impact on the staff.

A challenging environment due to COVID-19 regulations was the most frequently reported work challenge by the staff. This is aligned with studies reporting an association between restrictions to go out and residents’ distress 14,15. In one such study, the promotion of indoor activities helped occupy residents and maintain tranquillity, suggesting that, in future similar situations, this strategy may be helpful 15. Residents’ worries about COVID-19 infection were also frequently reported by the staff in the present study. Providing simple and understandable accurate information on COVID-19, including practical ways of how residents can protect themselves, may help minimise fears 23. On the other hand, reassuring SA compliance with safety measures, supporting residents, and limiting exposure to pandemic-related content on TV were adopted helpful strategies described by some authors and, thus, are suggested 15,18. Lack of support from community services was also frequently reported in this study. Worldwide, community services were indeed among the most affected mental health services during COVID-19 3. In response, many resorted to telemedicine but, frequently, unpreparedness and scarce resources hindered the transition to new technologies, which probably has also occurred in Portugal 3,24,25. To be prepared for potentially similar situations, it seems important to further analyse what hindered the support from community services and what was effective in tackling it. Aligned with what occurred in SAs worldwide due to mandatory lockdowns and visiting restrictions, the lack of residents’ access to usual social networks was another important challenge reported in the current study 14,15,17. Globally, some SAs sought to enable access to family and friends via new technologies, but again, several constraints may have limited this in Portugal. More than a third of the staff in the present study reported having to adapt too quickly to new ways of working, greater workload, and residents no longer getting an acceptable service. This is consistent with what happened in other mental health services worldwide, including SAs, due to staff shortages and unpreparedness 3,14,17. Aligned with other studies in SAs, the staff also reported infection-related worries in the current study 15,16. Interestingly, only roughly a quarter reported lack of PPEs or difficulty putting infection control measures into practice. On one hand, given a generalised lack of PPEs at the beginning of the pandemic and that data were collected in 2022, potential recall bias may partly explain these findings 26. Indeed, half of SAs’ had to ask residents to leave because of infection control issues, raising additional concerns about SAs’ structural conditions. In fact, a previous Portuguese study showed that more than half had no single bedrooms 27. On the other hand, the observation of COVID-19 consequences in other European countries (e.g., Italy) and fear of uncontrolled contagion influenced the way in which Portugal handled the pandemic 28-31. This fostered population compliance with infection control guidelines and contributed to very high vaccination rates in the country 28-31. Some useful strategies that Portugal adopted to face the pandemic (some indeed adaptable, at a microlevel, to SAs themselves) were, e.g., adapting the plans previously used to tackle pandemics; articulation between government, parliament, and other stakeholders (such as hospitals, researchers, and media); awareness and prevention campaigns; transparent communication; tackling misinformation and fake news; epidemiological surveillance; rapid updating of guidelines according to scientific evidence; and creating a task force to implement the vaccination plan 28-31.

Compared with the technical team, support workers reported fewer work challenges. Given that their main task is to monitor residents, it is possible that these did not have to substantially adapt their work nor had the burden of needing to justify the implemented COVID-19 restrictions to residents. Contrary to what was expected, the staff who already worked in mental health before COVID-19 reported more work challenges. It is possible that people who did not work in mental health before did not have any grounds for comparison between work conditions before and after the pandemic. Moreover, these were mostly younger and without children or elderly to take care of, which may have also contributed. Male staff more often reported a lack of PPEs or difficulty in putting infection control measures into practice, and the staff whose SAs were outside the LMA reported fewer challenges. However, the former may be better explained by the fact that most male workers were support workers (90% of male staff vs. 53% of female staff), who usually have closer and lengthier contact with residents; and the latter by the fact that only 16% of staff from outside the LMA had leadership tasks compared to 44% of staff from the LMA, which was associated with certain work challenges in the bivariate analyses.

More than a quarter of the staff reported having felt less able to do their job because their well-being had suffered, consistent with studies reporting a negative impact of the pandemic on HCWs 6-8,14,16,18. Unexpectedly, given different staff reported different challenges, there was no difference in the impact of the pandemic across the staff, suggesting that other factors, such as psychological or social factors, may have influenced it. Indeed, studies have associated certain factors, such as poor coping mechanisms and social support, with worse outcomes for HCWs 32,33. Reporting that residents were no longer getting an acceptable service and the risk of being infected at work were associated with a negative impact on the staff. This is consistent with two studies in mental health services, in which the staff perceived that the inability to provide appropriate service and continue therapeutic activities during COVID-19 contributed to worse well-being, by causing feelings of powerlessness and increasing stress 16, 34. The risk of infection has also been associated with a negative impact on HCWs in other countries 7,16,34-36. Working in crowded places during a respiratory pandemic may comprehensibly cause fears of contagion and negatively impact the staff. Promoting self-care, good-quality communication and information updates, and support mechanisms at the workplace is, thus, suggested 23.

Aligned with some studies in SAs, more than 40% of the staff perceived a negative impact of COVID-19 on residents consisting of relapse and deterioration in their mental health 15,17,18. However, caution is needed when interpreting this, given most participants were support workers, who had no formal education in mental health, and, thus, more studies are suggested.

Some of the implications of our findings for SA management in Portugal may also apply at the international level. Overall, SAs need to be prepared for future pandemics, a difficult endeavour which includes having emergency plans, feasible and adaptable to similar situations; improving housing conditions and ensuring single bedrooms for all (or most) residents; increasing human resources or being able to rapidly hire them; equipping SAs with new technologies and fostering its sensible use; continuously articulating with local health authorities and updating guidelines according to scientific evidence and professional guidance; developing work and personal well-being support mechanisms to staff; supporting residents and providing simple and understandable up-to-date information; and being ready to promote safe indoor activities and social interactions within SAs. For at least some of these recommendations to be possible, especially since most SAs are run by the third sector, governments may need to step in, namely, providing financial and logistic support, and regular audits. Furthermore, the articulation between SAs and health authorities needs to be safeguarded, and formal guidance swiftly provided when needed. Since SAs are structures located in the community, employing and supporting many people, improving their conditions is also important from a broader public health strategy point of view. Implementing some of these measures will not only better prepare SAs for similar situations, but also help improve regular care.

This is one of the very few studies analysing the work challenges of SAs’ staff during COVID-19, and, to our knowledge, the first to analyse the association between work challenges and the staff characteristics and the impact of the pandemic on the staff. It included participants with diverse sociodemographic characteristics from 32 SAs with different types of support and locations. Given SA’s global variation and that most data come from a limited number of countries, or even organisations, having data from various SAs of different countries is fundamental to better comprehend what happened during COVID-19 and prepare for the future. This study also has some limitations. Small sample size affected the precision of some estimates. Despite its rationale, our choice on how to categorise items’ scorings regarding work challenges may have influenced results. Data collection in 2022, 2 years after the beginning of the pandemic, may have led to recall bias. Due to the cross-sectional design, reverse causation between the studied variables cannot be excluded. Finally, given that only the staff participated, aspects specifically related to residents must be interpreted with caution. Future research should focus on what hindered the support from community services, its impact, and effective ways to dealing with this issue. In addition, further analysing the impact of the pandemic on the well-being of residents and the staff using a qualitative approach is suggested.

Conclusion

Several work challenges occurred in SAs during COVID-19, and certain staff characteristics influenced its report, namely, profession and years working in mental health. According to the staff, the pandemic had a negative impact on the staff and the residents. Overall, the implications of our results may include improving structural conditions, increasing financial and human resources, fostering the use of new technologies, enhancing workplace support mechanisms, supporting residents, providing clear and up-to-date information, and promoting safe indoor activities. These implications range from structural and financial to more direct clinical ones and require concerted efforts not only from SA management but also from the authorities.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants for their contribution. We would also like to thank the support for the accommodations involved for their support.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Author 4 (AE of the Portuguese Journal of Public Health) did not participate in the review process of this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Author 1 designed the study, analysed data, and drafted the initial version of the manuscript. Author 2, 4, and 9 supervised the study design. Author 3 was involved in data analysis. All authors contributed to the study design, interpretation of results, and manuscript revision and read and approved the final manuscript.