Introduction

Nail matrix nevi (NMN) are often considered in the differential diagnosis of acral melanoma, as they both present with melanonychia as a common feature1. In fact, congenital NMN frequently combine semiologic features of irregularity and asymmetry with a multicomponent pigmentation of the nail plate and surrounding tissue that could suggest malignancy1. Despite the invasive nature and emotional distress associated with nail matrix biopsy, it is crucial in cases with a high level of suspicion1,2. In this context, we report a case of congenital nail matrix nevus with recent suspicious changes, exploring its clinical and dermoscopic features.

Case report

A 49-year-old female patient was referred to our dermatology department due to a 1-month evolution of pigmentation in the proximal nail fold, associated with a longstanding longitudinal melanonychia on the second toe’s nail.

The patient reported having melanonychia since the 1st year of life and that it had not changed until a month before.

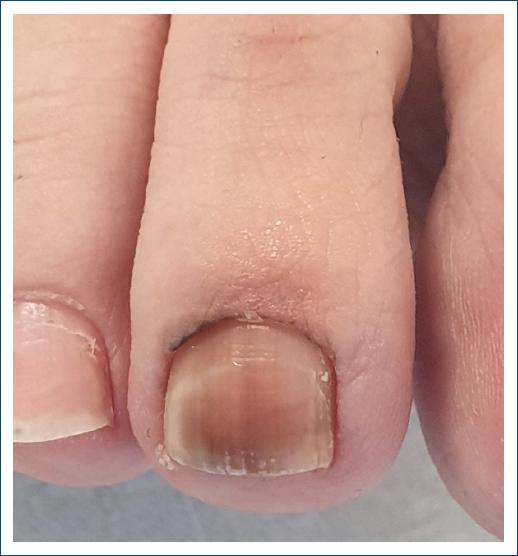

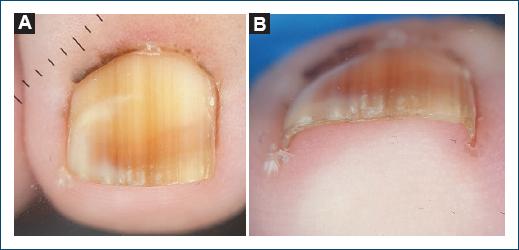

Physical examination showed light brown irregular longitudinal melanonychia covering over two-thirds of the nail without dystrophy, along with irregular monochromatic dark brown pigmentation in the proximal nail fold (Fig. 1). Dermoscopy revealed irregular light and dark brown longitudinal microlines in the dorsal nail plate and dark brown diffuse irregular pigmentation in the proximal nail fold (Figs. 2A and B).

Figure 1 Clinical findings of the nail plate – light brown irregular longitudinal melanonychia covering over two-thirds of the nail without dystrophy, along with irregular dark brown pigmentation in the proximal nail fold.

Figure 2 Dermoscopy of the nail. A: dermoscopy view of the nail plate: irregular light and dark brown longitudinal microlines with blurred lateral borders, covering over two-thirds of the nail plate, and dark brown diffuse irregular pigmentation in the proximal nail fold. B: dermoscopy view of the distal edge of the nail plate: irregular light and dark brown longitudinal microlines in the dorsal nail plate without any pigmentation in the hyponychium.

Recent changes prompted a nail matrix biopsy. The nail matrix biopsy was performed under local anesthesia with a proximal digital block. Subsequently, a tourniquet was applied, the proximal nail fold was retracted, and the nail plate was avulsed (Fig. 3). A tangential incisional biopsy was performed, and finally, the retracted fold and the avulsed nail plate were sutured.

Figure 3 Intraoperative view of the nail matrix biopsy showing the light and dark brown fibrillar pattern of the nail matrix.

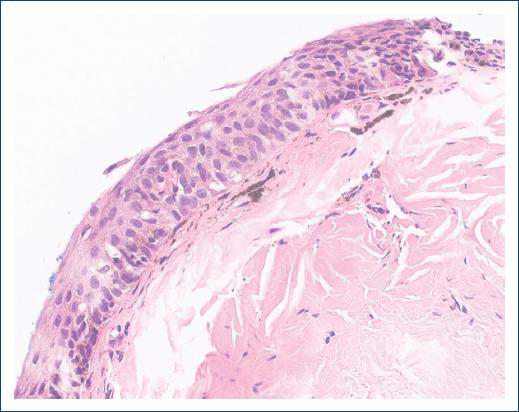

Histopathological examination revealed hyperpigmentation of the basal layer of the epidermis and coexisting melanophages in the dermis, without melanocytic junctional proliferation or dysplasia of the nail matrix, consistent with a nail matrix nevus (Fig. 4).

Figure 4 Histopathology of the nail matrix – hyperpigmentation of the basal layer of the epidermis and coexisting melanophages in the dermis, without melanocytic junctional proliferation or dysplasia (hematoxylin and eosin stain).

At the 3-month follow-up, the patient did not exhibit new changes in the nail or periungual tissue, and no dystrophy was observed.

Discussion

Congenital NMN are rare, with limited documented cases described in the literature1. They frequently exhibit clinical and dermoscopic distinctive features such as irregularity, asymmetry, and multicomponent pigmentation affecting the nail plate with or without involvement of the periungual tissues, raising concerns about potential malignancy1-3. The main clinical and dermoscopy feature of congenital NMN is the irregular pattern, defined by longitudinal microlines, irregularity in width, space, color, triangular shape, polychromasia, and irregular periungual pigmentation1. Furthermore, the most prevalent dermoscopic pattern of the periungual pigmentation has been described as a distal fibrillar (“brush-like”) pattern1.

The notable characteristic of melanonychia extending into the periungual tissues, known as Hutchinson’s sign, is traditionally associated with acral melanoma2,3. In addition to acral melanoma and congenital NMN, other differentials associated with Hutchinson’s sign include ethnic variations, trauma, systemic diseases, and drug adverse effects2,3.

Due to the rarity of congenital matrix nevi, there is a lack of consensus regarding their management. However, in the majority of congenital NMN cases, conservative management suffices, with clinical follow-up, including clinical photography and dermoscopy2. Performing a nail matrix biopsy is mandatory in suspicious cases, although it may have a risk of permanent scarring1,4,5.

Histopathologic analyses of nail matrix biopsies in congenital NMN are infrequent in the literature. Nevertheless, some cases have been described as junctional NMN or as functional melanocytic activation1. In our case, the biopsy showed features of melanocytic activation. In addition to congenital NMN, other causes of melanocytic activation include pregnancy, chronic trauma, nail-biting, drug adverse effects, and systemic diseases4, none of which were present in our case.

Aggressive procedures, such as complete excision involving the entire length of the nail matrix, are reserved for situations where melanoma cannot be ruled out even after an expert review of clinical and histopathologic findings2. However, subungual melanoma cases arising in congenital NMN are exceptionally rare, casting doubt on the accuracy of diagnoses1,6. Furthermore, there is currently no data in the literature regarding the evolution of congenital NMN into adulthood and their risk of malignant transformation.

Conclusion

This case highlights that congenital NMN frequently manifest clinically and dermoscopically alarming characteristics, mirroring those observed in subungual melanoma. This resemblance is particularly evident in the presence of the Hutchinson’s sign. Notably, the diagnostic criteria established for adult subungual melanoma may not be directly applicable or reliable when evaluating congenital NMN.