A 45-year-old female was referred to dermatology with a 1-year history of progressive skin induration of the limbs. She denied joint mobility restrictions and systemic symptoms.

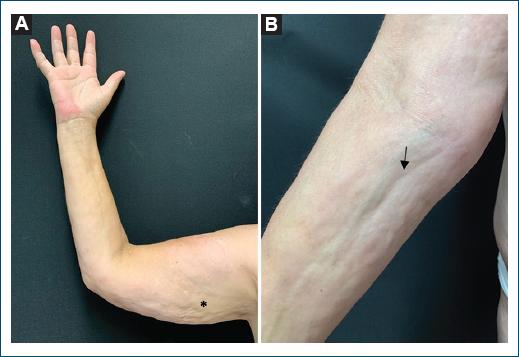

Clinical examination revealed symmetrical cutaneous induration and thickening of the legs, thighs, forearms, and arms with areas of orange peel-like appearance and skin depressions along the course of the superficial veins (“groove sign”) (Fig. 1A and B). Hands and feet were spared. Raynaud’s phenomenon was absent, and nail fold capillaroscopy was unremarkable. Laboratory findings demonstrated blood eosinophilia (1.9 × 109/L) and increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (120 mm/h).

Figure 1 Cutaneous induration and thickening of the right arm and forearm, with a “pseudo-cellulite” appearance on the arm (A: asterisk) and “groove sign” on the forearm (B: arrow).

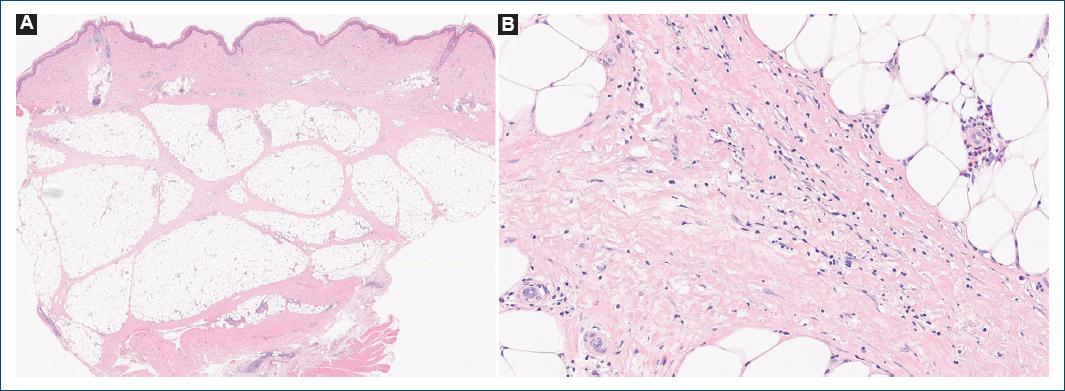

A full-thickness incisional biopsy was consistent with eosinophilic fasciitis, establishing the diagnosis (Fig. 2). The patient started treatment with prednisolone 1 mg/kg/day. However, considering the poor response, recently, weekly methotrexate was added.

Figure 2 A full-thickness incisional biopsy showed hypodermis septa thickness with a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, plasma cells, and occasional eosinophils extending into the lower dermis (H & E, magnification: A: ×1; B: ×40).

Eosinophilic fasciitis is a rare fibrosing disorder of muscle fascia of unknown etiology. Clinically, areas of orange peel-like (“pseudo-cellulite”) and linear depressions along the course of the superficial veins (“groove sign”) are characteristic1. This last physical finding is probably due to the relative sparing of the epidermis and superficial dermis around the vessels by the fibrotic process compared to the deep tissue2. A full-thickness biopsy including the fascia and/or magnetic resonance showing increased signal intensity within the fascia is crucial for diagnosis. The first line of treatment is systemic corticosteroids, which may be associated with corticosteroid-sparing agents, like methotrexate3.

Recognizing the clinical clues of eosinophilic fasciitis is important, as prompt diagnosis and treatment are essential to prevent the development of joint contractures, which are responsible for the high morbidity of this condition.