Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Vista. Revista de Cultura Visual

On-line version ISSN 2184-1284

Vista no.13 Braga June 2024 Epub June 30, 2024

https://doi.org/10.21814/vista.5484

Thematic Articles

Decolonial Twists and Turns of the Tupinambá Cloak: Three Women Artists and Their Work on the Artefact that Became an Icon of Brazilian Identity

1 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ensino e Relações Étnico-Raciais, Instituto de Humanidades, Artes e Ciências, Universidade Federal do Sul da Bahia, Bahia, Brazil

Este trabalho analisa as apropriações artísticas e simbólicas em torno do manto indígena tupinambá por meio do trabalho de três artistas brasileiras: Glicéria Tupinambá, Lívia Melzi e Lygia Pape. A partir da análise visual de suas poéticas, e estabelecendo uma reflexão entre estas criações e a dimensão iconográfica do artefato em determinados marcos históricos, pretendemos entender como as obras destas artistas estão entrelaçadas à lógica da arte contemporânea, levando em conta a contribuição que os estudos interdisciplinares podem ter para a compreensão deste momento em que as artes vêm sendo atravessadas por uma mudança de paradigma associada ao movimento decolonial, o que tem se reverberado na potencialização da natureza política e ativista do campo estético. Para além do debate sobre a repatriação de objetos de interesse etnográfico, apresentamos um estudo de caso envolvendo o percurso destas três artistas, cujas poéticas são analisadas a partir da metodologia da crítica da arte e de uma base teórica multidisciplinar, englobando autores da teoria e da história da arte, além dos estudos culturais e decoloniais. Não há dúvidas que a devolução do manto reacendeu de forma bastante expressiva os debates sobre a devolução de artefatos expropriados durante o período colonial brasileiro. Porém, nossa intenção é apontar para a importância do resgate das técnicas e dos gestos implementados pelas artistas, que permitem que novos mantos sejam realizados e reapropriados simbolicamente, fato congruente com a reflexão acerca do fazer político nos campos da estética e da museologia.

Palavras-chave: mulheres artistas brasileiras; manto tupinambá; arte indígena; decolonialidade; estudos decoloniais

This study delves into the artistic and symbolic appropriations of the indigenous Tupinambá cloak through the work of three Brazilian women artists: Glicéria Tupinambá, Lívia Melzi and Lygia Pape. Based on a visual analysis of their poetics and juxtaposing their creations with the iconographic dimension of the artefact in key historical milestones, we intend to understand the interconnectedness of these artists' works with contemporary art practices. In doing so, we seek to recognise the role of interdisciplinary studies in understanding this pivotal moment in art history, characterised by a paradigm shift influenced by the decolonial movement. This movement has notably elevated the political and activist dimensions of the aesthetic field. Besides discussing the repatriation of objects of ethnographic interest, this case study traces the artistic trajectories of these three artists, whose poetics are examined through the lens of art criticism. This analysis is underpinned by a multidisciplinary theoretical framework that draws from various authors from fields such as art theory and history, as well as cultural and decolonial studies. There is no doubt that the return of the cloak has significantly reignited debates about the return of artefacts expropriated during Brazil's colonial period. However, we intend to point out the importance of recovering the techniques and gestures used by the artists to create and symbolically re-appropriate new cloaks, which is congruent with the reflection on political making in the fields of aesthetics and museology.

Keywords: Brazilian women artists; Tupinambá cloak; indigenous art; decoloniality; decolonial studies

1. Introduction

In June 2023, Brazil was surprised by the announcement of the restitution of one of the best-preserved Tupinambá cloaks (Seta, 2023; Figure 1), a remnant from the colonisation period that had been kept in European institutions. The cloak, which will be returned to Brazil, is part of the ethnographic collection of the Nationalmuseet, Denmark's national museum, and will be integrated into the collection of the National Museum in Rio de Janeiro.

Following confidential negotiations, the Nationalmuseet announced the restitution through an official statement, highlighting that the donation represents a singular and substantial contribution to the restoration of the Brazilian museum's collection, which had suffered extensive damage during a major fire in 2018.

The return of the Tupinambá cloak marks an iconic moment in the "decolonial shift in Brazilian art" (Paiva, 2022, p. 15). A constant element in the colonisers' records of the former territory of Pindorama, the cloak is directly associated with the anthropophagic rituals of the Indigenous Tupinambá people, thus contributing to a rich cultural cartography surrounding the construction of an exotic symbolism of Brazil. Despite being declared extinct by the Brazilian Government in the 19th century, the Tupinambá continue to thrive, with active communities such as those residing in the Tupinambá Indigenous land of Olivença, located in the southern region of Bahia.

This study examines the artistic and symbolic appropriations of the cloak through the work of three women artists: Glicéria Tupinambá, Lívia Melzi and Lygia Pape. Based on an analysis of their poetics and by drawing parallels between these creations and the iconographic dimension of the artefact within certain historical milestones, our goal is to understand how a community reimagines its artefacts (Braga et al., 2022) or how the past is constantly reconfigured through images (Didi-Huberman, 2000/2008). In addition to the debate on the repatriation of ethnographically significant objects, our analysis focuses on the interpretation of artistic-cultural endeavours. This examination is conducted through the methodology of art criticism and supported by a multidisciplinary theoretical framework that incorporates insights from art theory and history, as well as cultural and decolonial studies.

There is no doubt that the restitution of the cloak has significantly rekindled debates about the restoration of artefacts expropriated during Brazil's colonial period. However, we intend to underscore the significance of recovering the techniques and gestures employed by the artists. These techniques enable the creation of new cloaks and their symbolic reappropriation, aligning with broader reflections on political agency within the fields of aesthetics and museology. Nevertheless, it is crucial to highlight that the return of the Tupinambá cloak makes significant contributions to multiple dimensions of the issue. It illustrates how art can drive different fields of influence, including museology, which is currently grappling with one of its most significant challenges to date: the decolonisation of collections.

The cloak falls into a category of artefacts whose original symbolism encompasses numerous attributes that are unfamiliar to Western culture. Mbembe (2018), referring to African culture and its forms of producing artworks and rituals, explains that an object exists only in relation to a subject, who, in a reciprocal state, bestows subjectivity upon any inanimate entity. This would be an impossible world to reconstruct within the confines of the Western museum universe, where objects are enduring proof of Europe's crimes of plunder and genocide.

By incorporating the Tupinambá cloak into their poetics, these artists redefine its power, pushing the boundaries of art's ontology to its limits. Particularly in the case of the artist Glicéria, this experience becomes an example to follow, almost a model for discussions about historical reparations and how we can engage with objects that, as Mbembe (2018) suggests, serve as mediators between humanity, ancestry, and vital power, vehicles of energy and movement, living materials cooperating with existence itself. Glicéria delves into the essence of the cloak's composition, tapping into its enchanted vitality, thereby proving that historical reparations cannot be superficially addressed through a mere "civilised" return of what was stolen. She seems to advocate that Indigenous peoples will not be content with the restitution of soulless objects.

Above all, we propose to understand how the works of these artists are intertwined with contemporary art practices. In doing so, we seek to recognise the contribution of interdisciplinary studies in understanding this pivotal moment in art history, characterised by a paradigm shift associated with the decolonial movement. This movement has notably elevated the political and activist dimensions of cultural production. The enduring dialogue between cultural studies and art history has revolved precisely around navigating visual culture beyond the perspective of representation (Gilroy, 1993; Mercer, 2012). Confronted with the phenomenon of the global decolonial shift in the arts, which prompts discussions about dismantling the Eurocentric artistic canon, our research directed its focus towards exploring the interplay between contemporary art and poetics centred on the theme of decoloniality. We conceive both socially engaged art and decolonial thought as elements rooted in the praxis of social transformation. Castellano (2021) contends that there is significant value in fostering dialogue between these traditions, as they share common goals and can complement and enhance one another. Such dialogue fosters experiences and challenges that disrupt the logic of neoliberal capitalism.

Our proposal aims to contextualise the projects of these three artists within the symbolism of the Tupinambá cloak within a broader framework of progressive action and thought in the arts. We aim to highlight the heterogeneous ways in which these creative currents contribute to understanding contemporary art experiences. Furthermore, we intend to explore how these exercises in radical imagination can inspire new artistic approaches. To do so, we situate Lygia Pape's work as a pivotal point (given her belonging to a previous generation) for comprehending the conceptual pillars that underpin contemporary art, which in Brazil at the time predominantly focused on issues of national identity through highly experimental propositions. Subsequently, we aim to analyse how the works of Glicéria and Melzi fit within the context of a new generation of artists whose poetics align with the decolonial agenda. Their works emphasise themes of ethnicity, race, and gender, thereby strengthening the connections between social injustice, territoriality, ecology, and other pertinent aspects. The term "decoloniality" serves as a fundamental conceptual framework to illustrate how the system of colonialist power has endured beyond historical colonialism, persisting in contemporary asymmetrical social and cultural relations that have been perpetuated over the past centuries (Walsh, 2009), evident in the operations of imperialism (Ballestrin, 2017). Decolonial thinking, stemming from a racial focus and its intersectional engagement with issues such as gender and ethnicity, has directly challenged the standards of Eurocentric art historiography. These shifts have influenced Latin American historiography, as evidenced by studies across various areas: (a) proposals conducted under the terminology "decolonial" of the modernity/coloniality/decoloniality group (Dussel, 2003; Mignolo, 2010; Quijano, 2005; Walsh, 2009); (b) theories related to Latin American, Asian and African studies (Canclini, 2015; Césaire, 1950/2020; Fanon, 2021; Said, 1978/2007; Spivak, 1985/2018); and (c) theories specifically addressing contemporary Indigenous art (Borea, 2021; Esbell, 2018; Lagrou, 2013; Pitman, 2021; Rojas-Sotelo, 2023; Suckaer, 2017).

2. About the Cloak's Return to Brazil

We must go back in time to understand the iconographic power of the Tupinambá cloak in the Western collective imagination. Its origins can be traced to the myriad narratives of European explorers in the Americas who, upon their return to the old continent, disseminated their epics with illustrations that sparked fervent interest in European society.

Within this framework, travelling scientists and artists are part of the protohistory of globalisation. They became - directly or indirectly agents in the production of the visual culture of the natural world that circulated and still circulates in Europe, influencing both its aesthetics and episteme. (Oliveira, 2022, p. 42)

The objects that were taken to European cabinets of curiosities reflected "a mindset of dominance over nature and cultures to be subjugated, contributing to the capitalist and encyclopaedic development of modern European culture" (Caffé et al., 2023, p. 261).

The Tupinambá cloak is among the most famous of all the pieces symbolic of the predatory period of colonial expansion in the Americas. The garment that will be returning to the country is beautifully crafted from the vibrant red feathers of the guará bird, or "fine scarlet", as described by the French friar André Thevet (1516-1590) in his exploratory accounts of 16th-century Brazil documented in his book Singularidades da França Antártica, a que Outros Chamam de América (The Special Features of Antarctic France, Otherwise Called America). Various historical events - such as Thevet's returning to Europe and gifting the cloak he had brought to a European nobleman - illustrate curious facets about the clothing worn by the Tupinambás on formal occasions, such as assemblies, the burials of loved ones and anthropophagic rituals. According to Chiarelli (2023), at the very beginning of the 16th century, the first appropriations of the Tupinambá cloak occurred in two forms: through exchanges of the garment between Whites and natives, allowing the former to create replicas of the garment to the old world; and through "graphic appropriation" evident in the illustrations produced for travelling artists' books, such as those found in the accounts of Hans Staden (1525-1576).

The illustrations featured in the book India Occidentalis and Historia Americae sive Novi Orbis by Théodore de Bry (1528-1598), the Belgian engraver who never ventured across the Atlantic, exemplify images produced in the 16th century that continue to circulate today, reinforcing the exotic imagery of the "new world". Beyond their documentary value, these images provoke semantic and visual discomfort (Oliveira, 2022). After all, "the savages represent cannibals in Renaissance and Mannerist bodies" (Oliveira, 2022, p. 43).

The cloak also found its way into court portraits. For instance, Maria Henrietta Stuart (1631-1660), princess of Orange, was portrayed wearing it over a white dress. Interestingly, the nobility in the 19th century also used the Tupinambá cloaks on Brazilian solemn occasions. That is illustrated by an episode where Pedro I (1798 -1834) adorned himself in a cloak inspired by Indigenous attire created by the painter Jean-Baptiste Debret (1768-1848) and documented in his work O Imperador (The Emperor) in the book Viagem Pitoresca e Histórica ao Brasil (Picturesque and Historical Journey to Brazil), from 1834. Another painting by the artist Pedro Américo (1843-1905) depicts Pedro II (1825-1891) wearing one of these cloaks in 1872 during the opening of the General Assembly in Rio de Janeiro.

Chiarelli (2023) states that both the depictions and the physical presence of the cloaks in Europe, from the colonial period onwards, played a decisive role in European and Brazilian iconography in the following centuries. Among the extant physical artefacts, there are currently over ten housed in European museums. According to Caffé et al. (2023), these artefacts can be found at various institutions, including the Musée des Arts Premiers du Quai Branly in Paris, France (one cloak); the Museum des Kulturem in Basel, Switzerland (one cloak); the Nationalmuseet Etnografisk Samling in Copenhagen, Denmark (one cloak, one cape and three hoods); the Musées Royaux d'Art et d'Histoire in Brussels, Belgium (one cloak); the Museo Nazionale di Antropologia e Etnologia in Florence, Italy (two cloaks); and the Museum Septalianum of the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milano, Italy (one cloak).

In 2000, the cloak garnered significant prominence in Brazil due to its display during the exhibition "Brasil + 500 Mostra do Redescobrimento" (Brazil + 500 Exhibition of Rediscovery), organised by the Fundação Bienal de São Paulo. The piece on display was the same one that is now set to return to Brazil. At that time, community leader Nivalda Amaral de Jesus, known as Amotara, and Aloísio Cunha da Silva, both Indigenous members of the Tupinambá community of Olivença (now deceased), were invited by the Folha de S. Paulo newspaper to visit the exhibition. Upon seeing the cloak, the community leader and her colleague cried, as documented in an article in the São Paulo newspaper. The Indigenous people said: "we can no longer make anything like this, a garment that drapes over our backs. Now I understand: when the colonisers took the cloak, they stole our power - and, weakened, we lost everything" (Roxo, 2021, para. 31)7.

This statement highlights how the artist Glicéria's reconstruction of the Tupinambá cloak offers an interesting perspective on the return of items usurped from their original communities by the colonising countries. The symbolic significance of an object that has been separated from its people for centuries is not only revived through the potential return of the piece but also through this active process of recreation. This goes beyond the static and material artefact itself, revealing that there is an agency awaiting repatriation and a deeper meaning to be experienced. Furthermore, it underscores the profound intersection of art and politics.

Following the Bienal, the cloak has become a symbol of the cultural resurgence of the Tupinambá people. Recently, the cacica Maria Valdelice Amaral de Jesus, daughter of Amotara, wrote the following to the management of the Nationalmuseet:

the dreams of our ancestors, which are also ours, endure. Amotara has preserved the memory of a Sacred Cloak among our people. Our cloaks are icons of our spirituality, and that is why we believe they should remain visible and vibrant, close to their people of origin. (Roxo, 2023, para. 8)

Cacique Rosivaldo Ferreira da Silva, Babau, from the Serra do Padeiro village

(Olivença), and Alexander Kellner, director of the Museu Nacional do Rio, also submitted letters. The three documents were handed over by the Brazilian ambassador in Denmark, Rodrigo de Azeredo Santos, to the director of the Nationalmuseet, who was moved by the correspondence and subsequently advocated for the return of the piece8.

3. Case Study: Three Women Artists Around the Cloak

3.1. Glicéria Tupinambá

Glicéria's engagement with the cloak is quite peculiar. With a background in anthropology, the artist, residing in the Serra do Padeiro village within the Tupinambá Indigenous territory of Olivença, illustrates how the intersection of anthropology and art in contemporary practices influences her approach and visual creation. Delving into anthropological studies to understand and represent her culture, as well as studying native rituals, traditions, symbols and identities, has been central to her artistic endeavours. This approach provides a critical perspective on cultural, social and political issues, challenging stereotypes and criticising power dynamics. While she was not directly involved in the bureaucratic negotiations for the cloak's return to Brazil, the artist wielded a strong influence on the decision due to the widespread publicity of her work.

It is also important to emphasise that the artist will represent Brazil at the “Venice Biennale” in 2024 and will be the first Indigenous Brazilian artist to present a solo exhibition at the event. This exhibition space, traditionally known as the "Brazil Pavilion”, has been renamed the "Hãhãwpuá Pavilion”. The name derives from the word used by the Indigenous Pataxó people to refer to the territory now recognised as Brazil before Portuguese colonisation. In a similarly innovative approach, the exhibition will be curated by three artists who are also of indigenous origin: Arissana Pataxó, Denilson Baniwa, and Gustavo Caboco.

In the early 2000s, Glicéria embarked on extensive theoretical and practical research on the cloak. The objective of reclaiming the artefact was to reconnect with traditional material and ritual practices of crafting the garment, which, for her, meant a reconnection with the territory, the enchanted (beings who do not physically inhabit this world) and Tupinambá cosmology. In 2006, at the request of Professor João Pacheco de Oliveira from the Museu Nacional do Rio de Janeiro (affiliated with the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro), the artist commenced crafting a cloak. This first version was featured in the exhibition "Os Primeiros Brasileiros" (The First Brazilians), curated by Pacheco and showcased pieces from the museum's collection unaffected by the 2018 fire (Oliveira, 2020). Subsequently, the artist crafted other pieces, revitalising ancestral techniques and using adapted materials. Through personal visits to the collections of European museums, such as the Musée du Quai Branly and the Nationalmuseet, the artist retrieved ancestral braiding techniques and various types of materials. One of the recent exhibitions where the artist actively participated was "Kwá Yepé Turusú Yuriri Assojaba Tupinambá: Essa É a Grande Volta do Manto Tupinambá" (Kwá Yepé Turusú Yuriri Assojaba Tupinambá: This is the Great Return of the Tupinambá Cloak), held in 2021 at the Galeria Fayga Ostrower (Brasília, Federal District) and Casa da Lenha (Porto Seguro, Bahia), and also exhibited in the Serra do Padeiro village itself.

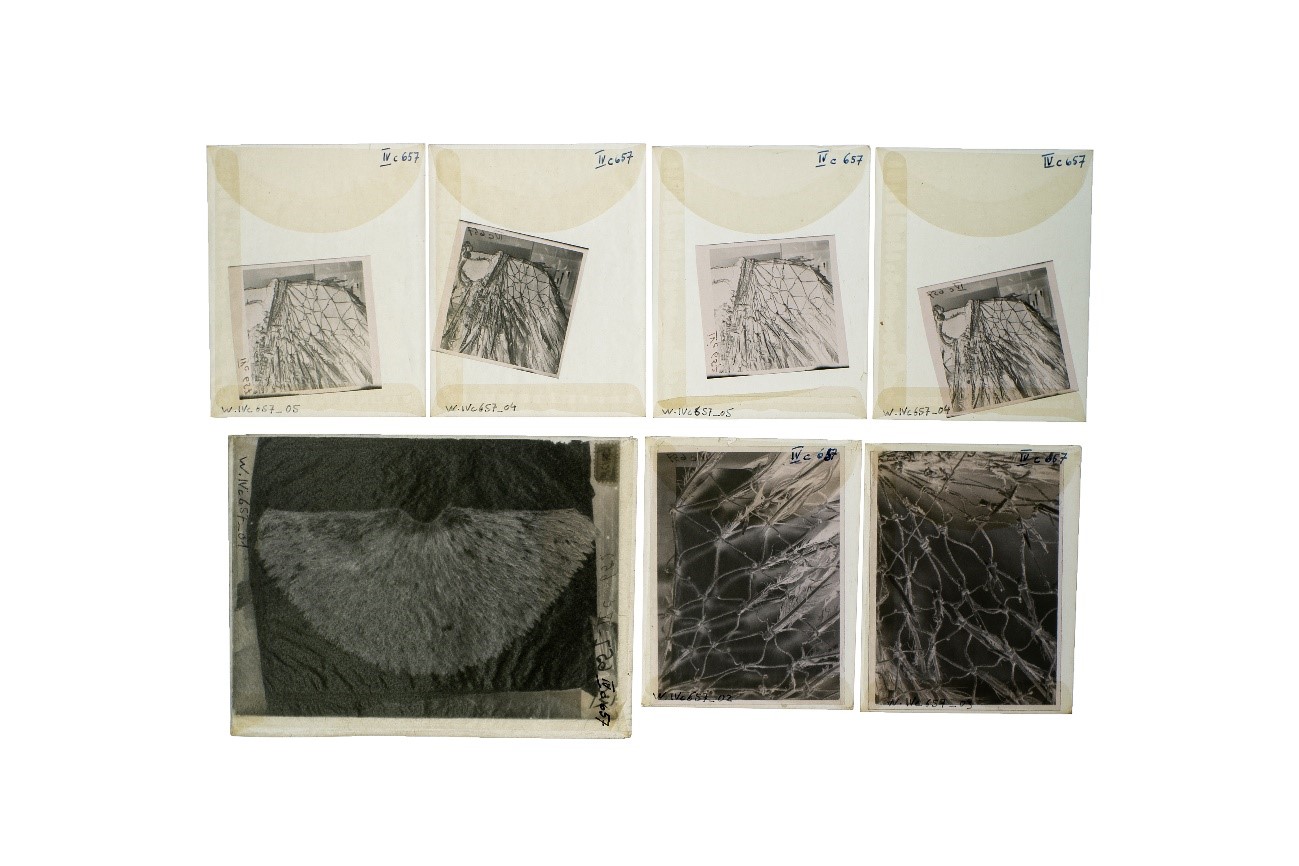

Recently, the Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand screened the feature film Quando o Manto Fala e o que o Manto Diz (When the Cloak Speaks and What the Cloak Says; 2023; Figure 2) by Glicéria and Alexandre Mortágua. The film documents the process of crafting the cloak, showing the uniqueness of this ancestral technology, such as the netting of the structure and the use of feathers from native birds. The film also reinforces the female perspective and the central role of Indigenous women, a recurring theme in Glicéria's speeches. In 2023, Casa do Povo, a socio-cultural space in São Paulo, also received one of the cloaks crafted by the artist. The object was featured in the exhibition "Manto em Movimento" (The Cloak in Movement; https://casadopovo.org.br/manto-em-movimento/), a documentary presentation that explored the artist's journey reconnecting with the cloak and linked it with the struggle for the demarcation of Tupinambá territory. Maps, iconographies, texts and travel records documented the artist's journey.

Imprensa MASP

Figure 2: Quando o Manto Fala e o que o Manto Diz (2023, video frame), by Glicéria Tupinambá and Alexandre Mortágua

In her creative process, Glicéria explains that the goal is not merely to replicate the appearance of the cloaks but to revive and reinvent the methods of their creation and the rituals they symbolise. She invokes the enchanted spirits, hoping they will guide her on these "reunion journeys" through her dreams. As an "artist-ethnographer", Glicéria draws upon the memory of the local community, conducting extensive iconographic and documentary research to understand how the Tupinambá people interact with both the material and immaterial worlds. That includes exploring practices such as the making of the needle, the jereré stitch (the base of the braid that holds the feathers), communicating with the birds and reconnecting with the forests. In the video "O Manto e o Sonho" (The Cloak and the Dream), produced by the Ciclo Selvagem project, Glicéria describes how the weaving of the cloak represents the sky and the stars. She also draws parallels between the weave and the chicken's skin. According to the artist, these are "cosmotechnics" (SELVAGEM ciclo de estudos sobre a vida, 2023).

3.2. Lívia Melzi

With a background in oceanography, the Brazilian artist, based in France, began her exploration of the cloak in 2018 by contacting the European institutions housing the artefact. She compiled an extensive catalogue detailing its history, documentation, and conservation methods. The references and themes inspiring her creations include the Manifesto Antropofágico (Anthropophagic Manifesto) by modernist writer Oswald de Andrade, published in 1928; the examination of the museum space as a locus of power over objects; and the literary and visual narratives produced by European travellers, like the German Johan Maurits (1604-1679), who was sent to the Brazilian colonies. Melzi uses video, photography and objects, among other elements, to compose a work imbued with colonial reimaginations. In “Tupi ou Não Tupi” (Tupi or Not Tupi), showcased in 2022 at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, the artist delves into Western representations of Tupinambá cloaks found in travel chronicles and the concept of cultural anthropophagy proposed by Oswald de Andrade, who declared in the Manifesto Antropofágico the famous sentence "Tupi or not Tupi, that is the question".

The symbolism of the cloak permeates other works by Melzi. An example of that is the work “Auto-Retrato” (Self-Portrait), created in partnership with Glicéria Tupinambá. In fact, this unveils a fascinating process of exchange between the artists. Melzi's website (https://liviamelzilab.com/) features videos, images and messages documenting Glicéria's creative processes in the making of the cloak. In another instance, a portrait by Melzi of a Tupinambá cloak from the Musée Art et Histoire in Brussels collection was incorporated in the installation “Qu'il Était Bon Mon Petit Français” (How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman; 2021), alongside an image of Théodore de Bry in a tapestry by Aubusson. The tapestry, like a painting, is hung on the wall. On the floor, Melzi has arranged a complex dining set based on the French art of table placement, which invites visitors to make an analogy with Édouard Manet's 1863 masterpiece “The Luncheon on the Grass”.

Melzi presents works with a predominantly decolonial slant, such as “Plat de Résistance” (Main Course; 2022), where she explores her dual cultural background (born in Brazil and living in France) in the Great Hall of the Brazilian Embassy in Paris, a majestic reception area adorned with bas-relief panels depicting hunting scenes. Against this backdrop, the artist filmed her first video work. It features a maître d'hôtel meticulously setting a grand table in accordance with the most refined French customs, complete with silverware, crystal and fine porcelain. The artist juxtaposes these traditions with the ancient anthropophagic rituals of the Tupinambás (equally elaborate but now extinct). In this contemporary anthropophagic banquet, plaster-cast legs and hands are served as food on trays (the pieces were crafted from the limbs of Guillaume Desanges, president of the Palais de Tokyo and artistic director of the Salon de Montrouge, where Melzi received the Grand Prix in 2021).

In “Sem Título” (Untitled; 2022), the artist photographs Glicéria's cloaks spread out on the wooden structure where they are made and displays them in two black and white images, one showing the front and the other the back (Figure 3). That is a metalinguistic operation, like a work within a work. An action that involves not only the complex web of formal references in her work but also her own subjective connection with her discursive space.

The artist explains a lengthy artistic process to understand her role.

I'm a White woman, a foreigner in France; we are Latinas, and we are not considered White here. I needed to understand this place of the “White” Brazilian living in Europe, and I needed to decide through which prism I wanted to look at this story. And the only possible prism was that of the “enemy". (Artista Brasileira Reflete Olhar Decolonial Sobre Mantos Tupinambás em Paris, 2022, para. 7)

The artist reflects on the notion of revenge, highlighting France's significant role in shaping Brazilian iconography9. Thus, "Lívia Melzi avenges memories", as Zalis (2022, p. 9) states. The artist also often speaks of her deep respect for Glicéria, acknowledging the different places of speech of each (a White woman and an Indigenous woman). This topic has sparked considerable controversy in Brazil (Figure 4).

3.3. Lygia Pape

A notable artist in the annals of Brazilian art history, Lygia Pape (https://lygiapape.com/artista/) was in the epicentre of the most inventive avant-garde in the country, as noted by Cocchiarale (1987). From the same generation and aesthetic affiliation as Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica, Pape was, like them, a member of the Frente Group (1953), the core of the concrete movement in Rio de Janeiro that fostered the emergence of the neo-concrete movement. In the later phase of her career, she created multiple works renowned for their experimental and innovative nature, including installations and interactive propositions that challenged the social implications of art and the roles of both the artist and the viewer, thereby restoring a series of concepts in these spheres.

Her most iconic works include “Divisor” (Divider), “Ovo” (Egg) and “Roda dos Prazeres” (Wheel of Pleasures), from the late 1960s (coinciding with the intensification of the military dictatorship), marked by a pivotal transition towards experimentation that introduced novel forms of engagement in contexts that transcended the traditional boundaries of the arts, targeting multiple audiences and wide-ranging urban spaces. While distinct in their approaches, these works maintained a clear propositional essence, revealing an expectancy for art to have an active presence in everyday life. According to Brett (2000), the “Divisor” stood as one of the most memorable "political-poetic images" of the 1960s, as it simultaneously brought together and yet individuated a crowd of people, forming an "ambivalent metaphor" that spoke to both individualism and community. It consisted of a large white cloth punctuated with openings through which individuals could insert their heads and try to move collectively, either accepting the flow or resisting the direction chosen by the group.

Drawing inspiration from the concepts of Oswald de Andrade, the artist also incorporated the symbolism of the Tupinambá cloak in her creation. An admirer and scholar of Brazil's native peoples, especially the Tupinambás, she kept several books and documents on the subject in her personal collection. So, in the 2000s, she created the Tupinambás series, with the most emblematic piece being the Tupinambá cloak, first exhibited at the "Mostra do Redescobrimento", the same event that displayed the original cloak seen by Amotara. "I wanted to make my 'Tupinambá Cloak' something extremely beautiful, like the original Tupinambá feather art, while also capturing the terror of death. Because both are present all the time" (Lygia Pape, n.d., para. 2) the artist expressed. Her exploration of this theme extended across various artworks, including pieces like “Memória Tupinambá” (Tupinambá Memory; 1996-1999), “Bus Stop” (1999), and “Carandiru” (2001). In “Memória Tupinambá”, the spheres, crafted from red feathers and bloody body fragments, exude provocative plastic energy, combining enigmatic visuality with beauty.

Regarding Pape's cloak, the first version was made for a solo exhibition at the São Paulo Cultural Centre in 1996. It featured a mirror with cockroaches on top and a dangling rope falling into the mirror. As people approached, they could project themselves onto it. The artist reflected on this creation, stating: "there is the issue of anthropophagy, of devouring the culture of the other" (Mattar, 2003, p. 89). A cloak that could not be physically created transformed into a photographic montage depicting a sprawling red cloud enveloping Guanabara Bay in Rio de Janeiro, the ancestral territory of the Tupinambá people. This representation addressed the idea of territory as a landscape, seeking to create an enchanting aura that unified the city despite its contradictions and the multiple meanings emerging from this vision embodied by the cloud-cloak (Machado, 2008).

The genesis of this series stemmed from Pape's close relationship with the writer Mário de Andrade. Upon Andrade's return to Brazil from his exile in Paris, he wanted to hold a grand exhibition on Brazilian Indigenous culture. Pape and Mário worked together on this project, slated for display at the Museu de Arte Moderna. However, a devastating fire engulfed the museum in 1978, nearly obliterating its entire collection and halting the project in its tracks10. Undeterred, Pape continued to create. In her Indigenous-themed creations, the artist delved into a wide range of aesthetic treatments, from polystyrene spheres with embossed cockroach motifs to spheres covered in red feathers. A notable example was the assembly of the cloak in the form of a large red net adorned with these feathered spheres, showcased at the "Mostra do Redescobrimento".

In the photographic composition “Bus Stop” (1999), Pape is depicted reading her daily newspaper, waiting for the bus, wrapped in an ethereal red cloak, resembling the cloud in Guanabara Bay, a kind of "Tupinambá cloak" for everyday use and constant historical reflection. Conversely, in “Carandiru” (2001), the idyllic charm of the cloud cloak and “Bus Stop” is dissolved: black and white images of Tupinambá Indians are juxtaposed with photos of incarcerated men in shades of red, insinuating a parallel between the extermination of the Indigenous people and the 111 inmates murdered by the military police in the massacre that took place in São Paulo's Carandiru prison in 1992, condoned by the Government. Exhibited in 2001 at the Centro de Arte Hélio Oiticica, the installation included a second space featuring an incessant red waterfall, echoing audio recordings of survivors' testimonies. The base of the waterfall, where the "blood" flowed, was shaped like a Tupinambá cloak.

4. The Twists and Turns Around the Cloak

We will analyse the work of these three artists, anchoring our discussions around decolonial premises and their impact on the status of contemporary art. We aim to ask (and answer) what commonalities and distinctions exist among these women artists' works. It is evident from our initial examination that all three artists offer a robust synthesis concerning the potential of aesthetic practices to challenge political hegemonies and contribute to the contemporary post-colonial project. Each artist approaches this task uniquely, shaped by their specific temporality and spatiality. Still, they share a common thread of employing what could be termed "aesthetic ethnography" or "ethnographic aesthetics", referring to Foster's (1996/2014) concepts, for whom the ethnographic artist has an affection for the real coupled with the need to redefine their individual and historical experience based on their traumas (racial, cultural and social).

Glicéria, an Indigenous woman, centres her aesthetic project on the revival of the cloak; this is the focal point of her continuous quest for original-subjectivitycollectivity. Adopting the roles of anthropologist-artist or artist-anthropologist, she rummages through archives, delivers lectures, and revisits ancient techniques, all while drawing inspiration from intuitive insights that echo the oral wisdom passed down by her ancestors. In this way, she becomes an aesthetic entity in her own right, mobilising various forces around her persona that yield tangible political outcomes, such as securing a presence at the "Venice Biennale" or the repatriation of a historical object.

By appropriating the tools used by the colonial regime of truths to impose marginalisation and epistemic violence, Melzi embarks on a quest for retribution, challenging the imperial ideologies that dictate regimes of representation and hierarchies of value. She does it, particularly within museum spaces.

Pape, on the other hand, retraces the reminiscences of a Brazil that was once completely oblivious to the indigenous struggle (demonstrating a temporal logic inherent to its moment). She rejuvenates its materiality by making reinterpreted objects imbued with expressive plasticity. This is evident in the words of the critic Osorio (2006), who highlighted the cloak created for the exhibition at the "Bienal de São Paulo" as the most impactful among all works in the Tupinambá series. "Nothing could have a greater political impact than bringing forth this memory of the defeated", the author observed, adding: "as always, the physical allure of their installations amplifies their political impact rather than obscuring it" (Osorio, 2006, p. 583).

What do these artists have in common? Beyond their approach to the decolonial debate and its ethnic bias, we believe they all articulate, in terms of language, an ontological intertwining with the status of contemporary art. Appropriation, self-referentiality, metalanguage and conceptuality are among the characteristics that permeate their works. Each of these artists, albeit with unique poetics, embraces the dissolution of material logic as the primary value attributed to the art object, emphasising the process of creation over the finished product. In their work, meaning transcends the physical confines of sculpture or the two-dimensional surface of the canvas. They conceive projects that incorporate a temporal dimension through experiential engagement and direct communication with the bodies of those interacting with the artwork (sometimes in its evolving process).

Thus, Glicéria extends a whole chain of creative powers triggered by her actions to a more profound level. The transformative potential of her artistic ingenuity is subversive, radical and collaborative, contributing to reconfiguring the conceptual repertoire for epistemic and bodily decolonisation. Paradoxically (or not), perhaps Glicéria's place of speech as an Indigenous woman amplifies the ways in which contemporary art operates. Her direct confluence - her very corporeality - with the decolonial debate may foster greater avenues for the radical essence of language and its profound connection with life. For example, Glicéria creates a product, yet this product has no meaning on its own. This relational and agential nature places her poetics in the field of contemporary dematerialisation since her strategy is to highlight the aesthetic, ethical and tactical performative significance of her engagement in actions/events/talks that engender encounters between herself and others. It is a work in perpetual political action; after all, the artist plays a pivotal role in the return of the cloak to Brazil, illustrating how the aesthetic can transcend its boundaries, that is, how the artistic field merges with life, particularly through its intersection with the political sphere.

As Rojas Sotelo (2017) points out, many contemporary Indigenous creators use a wide variety of media resources to "activate spaces where the oral and performative are amplified by the visual, where the creative act intertwines with the cultural event, including legal developments" (p. 5). Leveraging her identity as a woman, anthropologist, and Indigenous individual, Glicéria uses situations, materials and contextual narratives, both autobiographical and relational. Her work revolves around the ritual dimension of everyday life, the presence of ancestral elements and techniques such as appropriation, montage, situationism, recontextualisation, plastic action and quasi-legal action (her influence on the restitution of the cloak) and ethnography (as she has affirmed the role of women in making the cloaks, which was something not yet widely acknowledged by anthropologists).

That raises the question: what are the differences between these artists? One could argue that they lie in their "place of speech", which has been a central issue in decolonial debates in Brazil11. We do not suggest the concept is restrictive but rather something to examine. After all, regimes of exchange, such as language, structures, and cultures serve both as tools of oppression and as definers of political and creative cultures (Spivak, 1985/2018). It is worth considering that "it's in anthropophagic digestion that alterities are dynamised" (Zalis, 2022, p. 11). Glicéria, as an Indigenous person, also employs contemporary art strategies, thus renewing its ontology by being in this place of enunciation. Simultaneously, she invigorates her artistic practice by using the strategies bequeathed by the Western art tradition. This connection mainly stems from the removal of borders between the dimensions of life and art, a phenomenon common among Indigenous peoples and many contemporary Western artists.

Pape was not Indigenous, and as a White artist connected to the mainstream of the hegemonic cultural system, she presented what she could within her historical, subjective and situational limits. This does not diminish the significance of her work, which is of paramount importance in the history of art. However, it is noteworthy that the Tupinambá series, produced at a later stage in her career, does not have the same interactive and relational force as the earlier works that propelled her to the forefront of neo-concrete innovations, such as the anthological work “Divisor”. In her work Tupinambá, we observe a creative process focussed on the plastic construction of the object, where materiality takes precedence, despite openings for viewer participation and political critique.

Also, non-Indigenous, Melzi produces poetics through her collaboration with Glicéria, forming "ordinary affects" (Stewart, 2007), which prompt contemplation on the emotional currents guiding sensations and politics within everyday life and in art. The author clearly contends that the focus should not be on creating representations, known or knowable objects, but rather on cultivating an approach that suits its form, without the need for veracity. Consequently, artists extract cultural forms from the world and make them conducive to fascination. We can say that they intertwine in a mutual poetic endeavour, presenting a "living surface in action" (Stewart, 2007) and establishing an unconventional contact zone.

In the circularity between Melzi's and Glicéria's aesthetics, there is a communion extending beyond the physical object, akin to the ordinary affections that imbue things with the quality of being inhabited and animated (Williams, 1977). While lively objects emerge from this encounter (the cloaks produced by Glicéria and Melzi's works), the true potential of a renewing aesthetic seems to lie in the interplay of their mutual exchange.

The artists affirm Rancière's (2004) assertion regarding "artistic practices" as "forms of making and creating" that intervene in the broader distribution of making and creating. According to the author, the political dimension is inherently aesthetic and aesthetics, produced through artistic practices, is rooted in an elitist realm of production networks and self-perpetuating representational references that must be dismantled. Thus, the deconstruction of forms can contribute to more democratic politics and aesthetics, and this is intrinsically tied to Glicéria's activist work. Through Rancière's perspective, one can apply to his aesthetic regime an arrangement of the sensible in which art and life no longer appear separate from each other. While Melzi uses a post-colonial critical approach to art, Glicéria takes an embodied and disruptive poetic stance to the extreme, pushing for a redefinition of the relationship between art and artefact, aesthetics and colonial taxonomy, ultimately advocating for the implosion of the Western museum experience for racialised cultures. Glicéria creates with life.

It is noteworthy to consider the relevance of analysing these three artists within the framework of the decolonial debate, spanning from Pape to Glicéria/Melzi. Although she is not part of the historical modernist avant-garde, with the Tupinambá series, Pape sheds light on the controversies surrounding the concept of "cultural appropriation" recently emphasised by the decolonial movement. Many of these discussions resurfaced in Brazil in 2022, coinciding with the centenary of the "Week of 22", an iconic event in national modernism. While the historical avant-gardes sought to forge a national identity primarily based on the notion of social/geopolitical class - without the racial and gender issues - and on cultural appropriations based on references to original cultures, for contemporary artists (especially Black, Indigenous and LGBTQIA+ artists), this no longer holds relevance. One of the new lenses for reinterpreting this historical moment is the idea of "re-anthropophagy", embraced by artists to define the need to devour those who once devoured them12. Present-day artists demonstrate that the term so vaunted by Oswald de Andrade to describe the cultural assimilation of European values masked another form of devouring taking place concurrently, that of the culture of native and Afro-diasporic peoples by White artists from the aristocratic elite of the time.

The post-war generation, to which Pape belonged, would revisit the question of identity, bringing new elements that would give rise to the tropicalist movement. In analysing the artist's work, Brett (2000) argues that it was this rebellious vibrancy of the Brazilian avant-garde in the 1950s and 1960s that allowed her to deeply engage with the ideas of European abstraction without any excessive reverence or sense of inferiority. For the author, these artists could aim for the universal while at the same time being immersed in the local and in the particular (noting here that the category "universal" has been questioned since the "universal" is tied to a Eurocentric and American matrix in the history of art, that is, to a particular perspective). In this way, they were able to transcend the perception of being exotic or merely local variations of movements centred in the Northern hemisphere. Even though there was not yet a clearly stated decolonial approach during this period, artists like Pape hinted at the idea of the "pluriverse", as defined by Escobar (2020), which envisions a world where many worlds coexist. Pape once said that she had planned a work in which he would dig a big hole and remain inside it. When asked: what are you doing down there? She would reply: "I am looking for Brazilian roots" (Pape, 1998, p. 78).

The paradigm shift prompted by the decolonial transition rekindles the remnants of the debate on Brazilian identity, but now, from the viewpoint of those who were really excluded from its narrative, such as Black and Indigenous people. Through her poetics that critically unveil the post-colonial problem, Glicéria reveals that the time has come to have a voice free from the violent control of the colonisers.

5. Conclusion

Castellano (2021) argues that the historical indebtedness of Western and Eurocentric philosophy and critical thought to the anticolonial experience (which affects art criticism in similar ways) is aligned with the present blindness of many "global" views that still envision the South as a place of derivative ideas and practices, frozen in time, where originality, innovation, and historical relevance have been extirpated and translated elsewhere. According to the author, practice contributes to our understanding of cultural processes as much as theory. In this context, we strive to find common ground among the various participants in artistic collaboration, which can become a powerful source of critical thinking. Quoting Theodore Schatzki, who asserts that theory is always practised and that practice always contains a degree of (collective) thinking, Castellano (2021) illustrates how the multiple forms of radical creativity emerging from post-colonial and non-Western contexts can inform theory, and this exemplified by a work perpetuated by Glicéria. The artist imparts numerous lessons on the significance of experience and experimentation, the need to seek adaptable solutions to evolving challenges, the fruitful integration of pragmatism and utopian imagination, and the potential of contingent yet open sites.

The aesthetic revivals of the Tupinambá cloak can be understood through the concept of "performance constellations" (Fuentes, 2019), which refers to multiplatform patterns of collective action that coordinate asynchronous performances across various locations and temporalities. As multi-platform protest performances, the performance constellations led by Pape, Melzi and Glicéria respond to the challenges posed by changes in contemporary art, prompting the artists to recalibrate their tactics, targets and objectives. These artists demonstrate how aesthetics can be viewed as a potent force with political agency, capable of subverting established "regimes of truth" (Hall, 2001) and modes of representation (Hall, 1997).

By linking aesthetics and politics, "sharing the sensible" implies the reorganisation of roles, spaces and expressions, challenging preconceived ideas. According to Rancière (2004), any aesthetic expression, by shaping new sensibilities, is inherently political: politics and aesthetics intersect as they reorganise the material of the community, thereby generating experiences that reconstruct the ways of creating, observing, feeling and communicating in a challenging way. Basbaum (2013) introduces the term "artist-etc." to acknowledge the artist who increasingly sees themselves as a performance device, challenging the traditional role of the artist and fostering a connection between those who create and those who enjoy a continuous flow between individuals, groups, collectives and institutions. Glicéria, Pape and Melzi are quintessential artists-etc.,through their poetics, they effectively address the primary question posed in this article: how do communities reimagine their objects?

The essence of the answer lies in Glicéria's poignant analogy, where she likened her culture to a shattered clay pot,

a full pot that was hurled onto a stone surface, shattering into tiny pieces, and we had to do this mosaic work, meticulously reassembling the pieces and glueing them back together. It will be the same pot, even if it's cracked, but that doesn't matter. (Tupinambá, 2021, p. 19)

Her words echo what Zalis (2022) expressed: "in the shards left by the colonial genocide, the Tupinambá Cloak cannot simply be replicated as it once was, nor does it make sense to do so" (p. 9).

Regarding the other initial inquiry about how the past is reshaped through imagery, this statement resonates: "the unsubmissive fate of images that necessarily work against their intended purpose. Theodore de Bry sought to depict cannibalism, yet inadvertently infused the political imagination with a philosophy of difference" (Zalis, 2022, p. 5). Through their meticulous efforts with the cloak, salvaging historical shards and splinters, Glicéria, Melzi, and Pape contribute to reimagining the multiple possibilities of Brazilian anticolonial symbolism. In doing so, they recreate the past through a poetics of difference.

REFERENCES

Artista brasileira reflete olhar decolonial sobre mantos tupinambás em Paris. (2022, 21 de outubro). UOL. https://noticias.uol.com.br/ultimas-noticias/rfi/2022/10/21/artista-brasileira-reflete-olhar-decolonial-sobre-mantos-tupinambasem-paris.htm?cmpid=copiaecola [ Links ]

Ballestrin, L. M. (2017). Modernidade/colonialidade sem “imperialidade”? O elo perdido do giro decolonial. Revista de Ciências Sociais, 60(2), 505-540. https://doi.org/10.1590/001152582017127 [ Links ]

Basbaum, R. (2013). Manual do artista-etc. Beco do Azougue. [ Links ]

Borea, G. (2021). Configuring the new Lima art scene: An anthropological analysis of contemporary art in Latin America. Routledge. [ Links ]

Braga, A. L., Streva, J. M., & Zalis, L. Z. (2022, 10 de novembro). Especular pactos sobre o comum. La Escuela. https://laescuela.art/es/campus/library/mappings/especular-pactos-sobre-o-comum-ana-luiza-braga-juliana-streva-e-liorzisman-zalis-pt [ Links ]

Brasil + 500 Mostra do Redescobrimento. (2023, 29 de novembro). Editores da Enciclopédia. https://enciclopedia.itaucultural.org.br/evento217210/brasil500-mostra-do-redescobrimento [ Links ]

Brett, G. (2000). A lógica da téia in Gávea de Tocaia/Lygia Pape. Cosac & Naify Edições. [ Links ]

Caffé, J., Gontijo, J., Tugny, A., & Tupinambá, G. (2023). As muitas voltas dos mantos tupinambás. In B. Belisário, E. Rosse, & R. Tugny (Eds.), Poéticas ameríndias: Memórias territórios (pp. 257-288). Editora Escola de Música da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. [ Links ]

Canclini, N. G. (2015). Culturas híbridas. Estratégias para entrar e sair da modernidade. Edusp. [ Links ]

Castellano, C. G. (2021). Art activism for an anticolonial future. State University of New York Press. [ Links ]

Césaire, A. (2020). Discurso sobre o colonialismo (C. Willer, Trad.). Veneta. (Trabalho original publicado em 1950) [ Links ]

Chiarelli, T. (2023). O manto tupinambá como matéria e símbolo - Algumas anotações. Arte&Crítica, (66), 64-83. [ Links ]

Cocchiarale, F. (1987). Abstracionismo geométrico e informal: A vanguarda brasileira nos anos cinquenta. Funarte. [ Links ]

Didi-Huberman, G. (2008). Ante el tempo. Historia del arte y anacronismo de las imagines (A. Oviedo, Trad.). Adriana Hidalgo Editora. (Trabalho original publicado em 2000) [ Links ]

Dussel, E. (2003). Transmodernidad e interculturalidad: Interpretación desde la filosofía de la liberación. Erasmus Revista Para el Diálogo Intercultural, 5(1-2), 1-26. [ Links ]

Esbell, J. (2018, 22 de janeiro). Arte indígena contemporânea e o grande mundo. Revista Select. https://select.art.br/arte-indigena-contemporanea-e-o-grandemundo/ [ Links ]

Escobar, A. (2020). Pluriversal politics: The real and the possible. Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Fanon, F. (2021). Black skin, white masks. Penguin Classics. [ Links ]

Foster, H. (2014). O retorno do real: A vanguarda no final do século XX (C. Euvaldo, Trad.). Cosac Naify. (Trabalho original publicado em 1996) [ Links ]

Fuentes, M. A. (2019). Performance constellations: Networks of protest and activism in Latin America. University of Michigan Press. [ Links ]

Gilroy, P. (1993). Small acts: Thoughts on the politics of Black cultures. Serpents Tail. [ Links ]

Hall, S. (1997). Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices. SAGE. [ Links ]

Hall, S. (2001). Foucault: Power knowledge and discourse. In M. Wetherell, S. Taylor, & S. J. Yates (Eds.), Discourse theory and practice: A reader (pp. 72-81). SAGE. [ Links ]

Lagrou, E. (2013). Arte indígena no Brasil: Agência, alteridade e relação. C/Arte. [ Links ]

Lygia Pape. (s.d.). Manto tupinambá. https://lygiapape.com/tag/manto-tupinamba/ [ Links ]

Machado, V. R. (2008). Lygia Pape - Espaços de ruptura [Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade de São Paulo]. Biblioteca Digital USP. https://doi.org/10.11606/D.18.2008.tde-19082008-135305 [ Links ]

Mattar, D. (2003). Lygia Pape/Coleção perfis do Rio. Relume Dumará. [ Links ]

Mbembe, A. (2018, 5 de outubro). À propos de la restitution des artefacts africains conservés dans les musées d’occident. Analyse Opinion Critique. https://aoc.media/analyse/2018/10/05/a-propos-de-restitution-artefacts-africainsconserves-musees-doccident/ [ Links ]

Mercer, K. (2012). Art history and the dialogics of diaspora. Small Axe, 16(2), 213-227. https://doi.org/10.1215/07990537-1665632 [ Links ]

Mignolo, W. (2010). Aiesthesis decolonial. Calle 14, 4(4), 10-25. [ Links ]

Mombaça, J. (2021) Não vão nos matar agora. Cobogó. [ Links ]

Oliveira, E. J. (2022). A fábrica do selvagem e o choque das imaginações. Uma leitura pós-etnográfica da obra de Denilson Baniwa. Quaderni Culturali, 4, 41-51. https://doi.org/10.36253/qciila-2061 [ Links ]

Oliveira, J. P. (2020). Os primeiros brasileiros. Arquivo Nacional-Museu Nacional. [ Links ]

Osorio, L. C. (2006). Lygia Pape - Experimentation and resistance. Third Text, 20(5), 571-583. https://doi.org/10.1080/09528820601010403 [ Links ]

Paiva, A. S. (2022). A virada decolonial na arte brasileira. Mireveja. [ Links ]

Pape, L. (1998). Entrevista a Lúcia Carneiro e Ileana Pradilla. Nova Aguilar. [ Links ]

Pitman, T. (2021). Decolonising the museum: The curation of Indigenous contemporary art in Brazil. Boydell & Brewer. [ Links ]

Quijano, A. (2005). Colonialidade do poder, eurocentrismo e América Latina. In E. Lander (Ed.), A colonialidade do saber: Eurocentrismo e ciências sociais. Perspectivas latino-americanas (pp. 118-142). CLACSO. [ Links ]

Rancière, J. (2004). The politics of aesthetics: The distribution of the sensible. Continuum. [ Links ]

Ribeiro, D. (2017). O que é lugar de fala? Letramento. [ Links ]

Rojas-Sotelo, M. L. (2023). The tree of abundance: On the Indigenous emergence in contemporary Latin American art. Arts, 12(4), 1-29. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12040127 [ Links ]

Rojas Sotelo, M. (2017). Soberanía visual en Abya Yala. In M. Rojas Sotelo, C. Díaz, E. Giraldo, C. O. Fino, & E. Flórez (Eds.), Reconocimientos a la crítica y el ensayo: Arte en Colombia (pp. 5-15). Ministerio de Cultura; Universidad de los Andes. [ Links ]

Roxo, E. (2021, novembro). Longe de casa: O fascínio, a dor e os equívocos em torno dos mantos tupinambás na Europa. Folha de S. Paulo. https://piaui.folha.uol.com.br/materia/longe-de-casa-2/ [ Links ]

Roxo, E. (2023, 27 de junho). A volta do manto tupinambá: Museu Nacional da Dinamarca vai devolver para o Brasil relíquia sagrada que está na Europa desde o século XVII. Folha de S. Paulo. https://piaui.folha.uol.com.br/volta-domanto-tupinamba/ [ Links ]

Said, E. (2007). Orientalismo (R. Eichenberg, Trad.). Companhia das Letras. (Trabalho original publicado em 1978) [ Links ]

SELVAGEM ciclo de estudos sobre a vida. (2023, 1 de junho). 4 - Memórias ancestrais - O manto e o sonho - Glicéria Tupinambá [Vídeo]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=36HUTPYRNpE [ Links ]

Seta, I. (2023, 28 de junho). Raríssimo manto tupinambá que está na Dinamarca será devolvido ao Brasil; peça vai ficar no Museu Nacional. G1. https://g1.globo.com/ciencia/noticia/2023/06/28/rarissimo-manto-tupinamba-que-esta-nadinamarca-sera-devolvido-ao-brasil-peca-vai-ficar-no-museu-nacional.ghtml [ Links ]

Spivak, G. C. (2018). Pode o subalterno falar? (S. Almeida, M. Feitosa, & A. Feitosa, Trads.). Editora UFMG. (Trabalho original publicado em 1985) [ Links ]

Stewart, K. (2007). Ordinary affects. Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Suckaer, I. (2017). Arte indígena contemporáneo: Dignidad de la memoria y apertura de cánones. Samsara/Fonca. [ Links ]

Tupinambá, G. (2021). O manto é feminino. Assojaba Ikunhãwara. In J. Caffé, J. Gontijo, A. Tugny, & G. Tupinambá (Eds.), Kwá yepé turusú yuriri assobaja tupinambá: Essa é a grande volta do manto tupinambá (pp. 18-25). Conversas em Gondwana. [ Links ]

Walsh, C. (2009). Interculturalidad, Estado, sociedad: Luchas (de)coloniales de nuestra época. Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar/Abya-Yala. [ Links ]

Williams, R. (1977). Marxism and literature. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Zalis, L. Z. (2022). A vingança das imagens. In Tupi or not tupi (pp. 5-11). Galeria Ricardo Fernandes. [ Links ]

1In an article, author Elisangela Roxo (2021) pointed out two mistakes made by the institution on the plaques identifying the piece. Not only did it erroneously describe the Tupinambás as "Amazonian" when they were actually coastal and native to the Atlantic Rainforest, but it also falsely stated that the people had become extinct.

2In another article, Elisangela Roxo (2023) recounts that, in 2021, Rodrigo de Azeredo Santos read the article she had written - Roxo (2021). The journalist explains that the ambassador then learnt that Brazil had never officially claimed the return of the artefact. He then set about gathering the necessary letters to formalise the request.

3In an explanation emailed to this author in February 2024, the artist states the following: "the term 'enemy', in this context, was used to refer to the 'other' within the anthropophagic ritual (whose historical sources - despite contemporary texts, are all European and which I, Lívia, consider a colonial fiction). This 'other' is the person who is devoured and whose virtues are absorbed. In this exhibition, the institution's director embodied this 'enemy': a White French man overseeing the largest contemporary art centre in Europe. The three elements within the exhibition room (Musée du Quai Branly, "Plat de Résistance" and "Théâtre Cannibal" de Bry) inhabit the universe of this 'enemy': the museum, the dining table and the Aubusson tapestries, historically commissioned for the French monarchs. I worked with elements ingrained in the collective imagery (culture?) of the devoured. My place, in this and exclusively in this context, was ambiguous because I could either sit at the table to eat this enemy (since I am an artist, a woman, an immigrant... and 'anthropophagic' in modernist terms), or I could be the one devoured, the Frenchwoman, the 'other'. My circumstances align me closely with this 'other'. Throughout the preparation of this exhibition, curator Daria de Beauvais and I asked ourselves the following questions: who is speaking, and to whom am I speaking?" (Lívia Melzi, personal communication, February, 2024).

4After the fire, critic Mário Pedrosa proposed the re-establishment of the Museu de Arte Moderna in Rio de Janeiro. He proposed establishing the Museu das Origens (Museum of Origins), formed by five independent museums: the Museu do Índio (Museum of the Indian), the Museu da Arte Virgem (Museum of the Untouched Art), the Museu de Arte Moderna (Museum of Modern Art), the Museu do Negro (Museum of the Black) and the Museu de Artes Populares (Museum of Popular Arts; Brasil + 500 Mostra do Redescobrimento, 2023).

5Beyond the simple polarisation of the superficial idea of "who can say what", Ribeiro (2017) delves into the subject and makes it clear, asserting that the "place of speech" should be understood as a space of situated consciousness, irrespective of the enunciator's place, which aligns with Jota Mombaça's (2021) perspective of the same subject. The author goes through the issue historically, starting with the erasure of Black women by liberal feminist movements, illustrating how various discussions have since emerged, highlighting the intersections of race, gender, ethnicity, and other factors. In Brazil, discussions on this topic have been recurring, especially on social media. These debates often adhere to the essentialist view of identity. For instance, there is a notion that if Melzi is a White woman, she cannot address Indigenous issues in her work. From our standpoint, this is not a problem. If the concept has been used as an instrument that either grants or withholds authority to "speak based on the political positions and markers that a given body occupies in a world organised by unequal forms of distribution of violence and access" (Mombaça, 2021, p. 85) then it is crucial to consider that in the arts, the notion of "situated knowledge" (p. 87) may be more pertinent tor advocating the assumption that the place of speech is not directly tied to identity essentialism, but rather with "positions". After all, these are people, materialities, positions, and bodies that definitely inhabit marginalised spaces, not inscribed in time and space like hegemonic (White and cis) bodies. Mombaça (2021) argues that the discussion is not about "who" can speak but "how". According to the author, activists from the place of speech challenge a certain privileged way of articulating truths, intelligibility and political listening. In this sense, cis White people could not speak as if they were detached from their places of speech either, naturalising their own authority.

6The reinterpretation of the term had already gained momentum with theexhibition "ReAntropofagia" in 2019 at the Centro de Artes da Universidade Federal Fluminense, whose curators, including the artist Denilson Baniwa, who presented his homonymous canvas depicting the severed head of the writer Mário de Andrade (1893-1945), author of the book Macunaíma, which drew inspiration from Indigenous narratives.

Received: November 29, 2023; Revised: January 19, 2024; Accepted: January 19, 2024

text in

text in