Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Vista. Revista de Cultura Visual

On-line version ISSN 2184-1284

Vista no.13 Braga June 2024 Epub June 30, 2024

https://doi.org/10.21814/vista.5528

Visual Projects

Repairing Colonial Violence Against Women: Revisiting Mulheres Sempre Presentes

1 Instituto de Comunicação da NOVA, Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas, Universidade NOVA de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal

2 Centro de Investigação em Comunicação Aplicada, Cultura e Novas Tecnologias, Universidade Lusófona, Lisbon, Portugal

3 Museu Nacional de História Natural e da Ciência, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal

4 Arquivo de Documentação Fotográfica, Direção Geral do Património Cultural, Sacavém, Portugal

Este ensaio retoma o projeto Mulheres Sempre Presentes, realizado para a exposição “O Impulso Fotográfico. (Des)arrumar o Arquivo Colonial”. A proposta ressignifica fotografias analógicas de antropologia física colonial portuguesa através de procedimentos de descontextualização e recontextualização, tentando interromper a reprodução de estereótipos negativos sobre as mulheres negras fotografadas, os quais abundam no arquivo das missões de antropologia colonial de onde os retratos foram selecionados. A escolha de retratos de mulheres pretende homenagear a sua presença nas longas lutas levadas a cabo pelas populações negras em diversos momentos da história e afirmar o seu papel de agentes do processo histórico, em sociedades patriarcais, tanto europeias como africanas tradicionais, que tendem a relegá-las para segundo plano. O ensaio conjuga, ainda, diferentes vozes e reflexões das suas autoras, sob influência do texto de Spivak (1988/2021) Pode a Subalterna Tomar a Palavra?, que aborda as condições de fala e de escuta das mulheres e interroga a sua condição de subalternidade.

Palavras-chave: retrato de mulheres; antropologia física; bertillonage; ressignificação; reparação

This essay resumes the project Mulheres Sempre Presentes (Women Always Present) produced for the exhibition "O Impulso Fotográfico. (Des)arrumar o Arquivo Colonial" (The Photographic Impulse. (Dis)placing the Colonial Archive). The proposal aims to resignify analogue photographs of Portuguese colonial physical anthropology by removing them from their original context and inserting them into a new one. The goal is to stop the reproduction of negative stereotypes about the Black women in these photographs. These stereotypes are prevalent in the archive of colonial anthropology surveys, from which the portraits were selected. The choice of Black women's portraits is intended to honour the enduring struggles undertaken by Black populations throughout history and to underscore their role as agents of historical processes in patriarchal societies, both European and traditional African, where they are often marginalised. The essay also combines the different voices and reflections of its authors, drawing inspiration from Spivak's (1988/2021) essay Pode a Subalterna Tomar a Palavra? (Can the Subaltern Speak?), which addresses the conditions of women when speaking and being heard and interrogates their position of subalternity.

Keywords: women's portraits; physical anthropology; bertillonage; resignification; reparation

1. Introduction

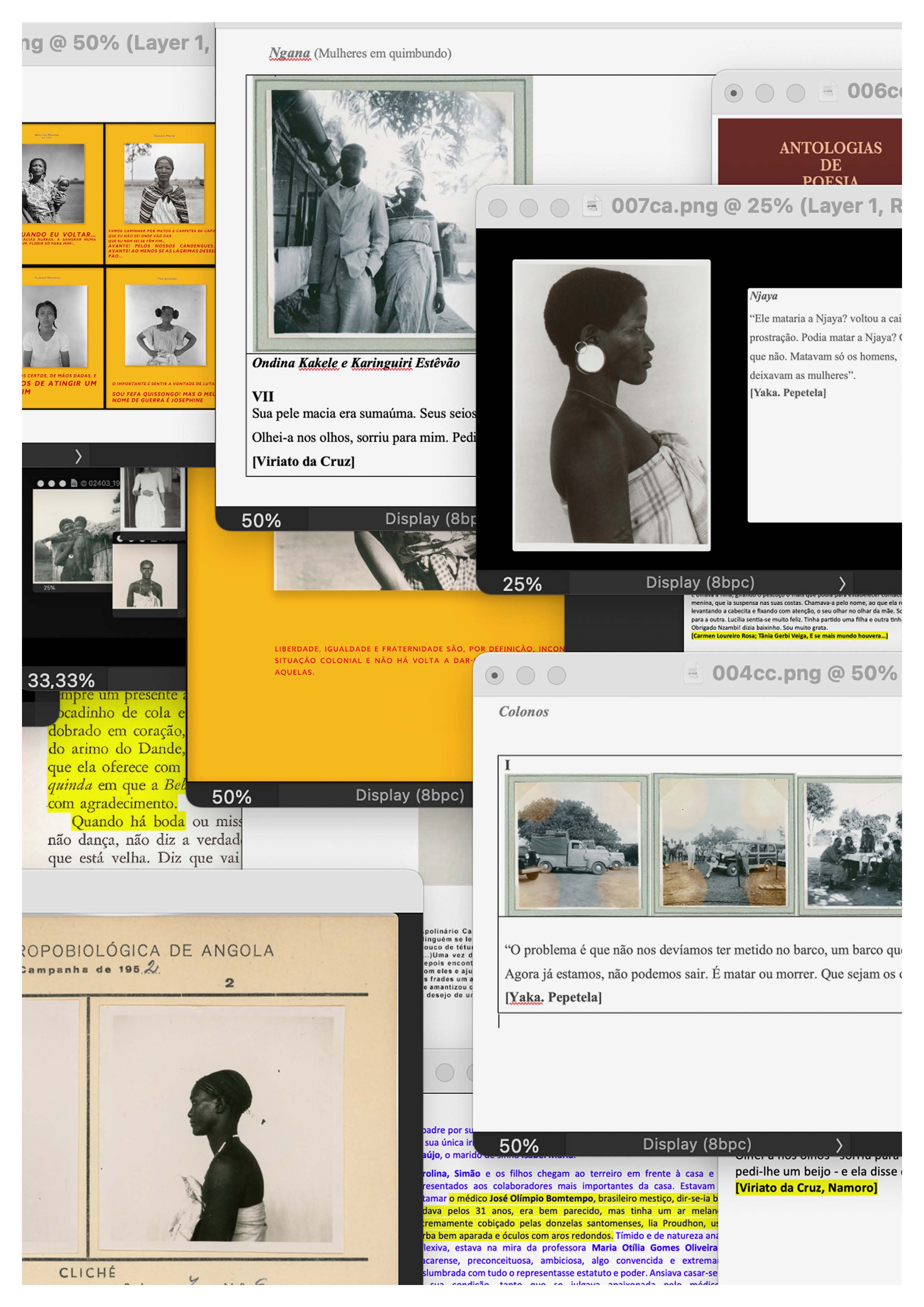

The essay in this edition of Vista reflects the development of Carmen Loureiro Rosa, Soraya Vasconcelos, and Catarina Mateus's project Mulheres Sempre Presentes (Women Always Present). Teresa Mendes Flores joins us in this reflective movement, which is resumed here.

The project stemmed from discussions held within the curatorial group, where we, alongside our colleagues, contributed to the conception of the exhibition "O Impulso Fotográfico. (Des)arrumar o Arquivo Colonial" (The Photographic Impulse: (Dis)placing the Colonial Archive), showcased at the National Museum of Natural History and Science at the University of Lisbon since December 21, 2022. It emerged from a research project with the same title, which delved into the visual production, predominantly photographic and cinematic, of colonial geography and anthropology surveys to Portuguese colonial territories between 1890 and 1975.

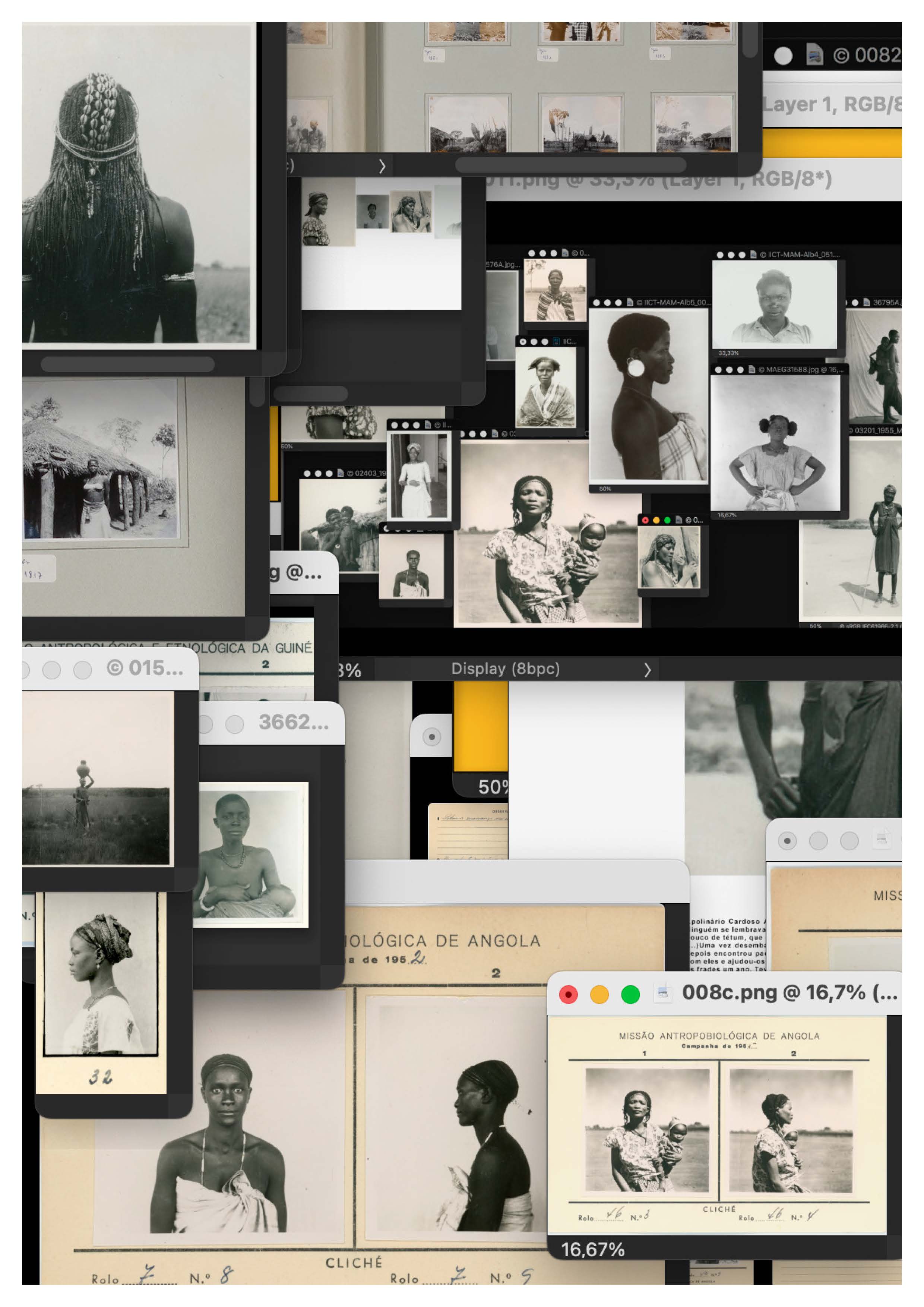

In our pursuit of a sensitive approach, we encountered thousands of portraits from Portuguese colonial physical anthropology, characterised by processes and practices that dehumanised and objectified the subjects captured in the images. Finding a way to depict these photographic practices without further objectifying the individuals photographed presented us with a significant challenge. Mulheres Sempre Presentes emerged as one potential solution. It employs strategies of resignification to challenge the reproduction of social and photographic stereotypes, which frequently operate on the subconscious level, perpetuating exclusionary, discriminatory, and racist representations by imposing and naturalising them.

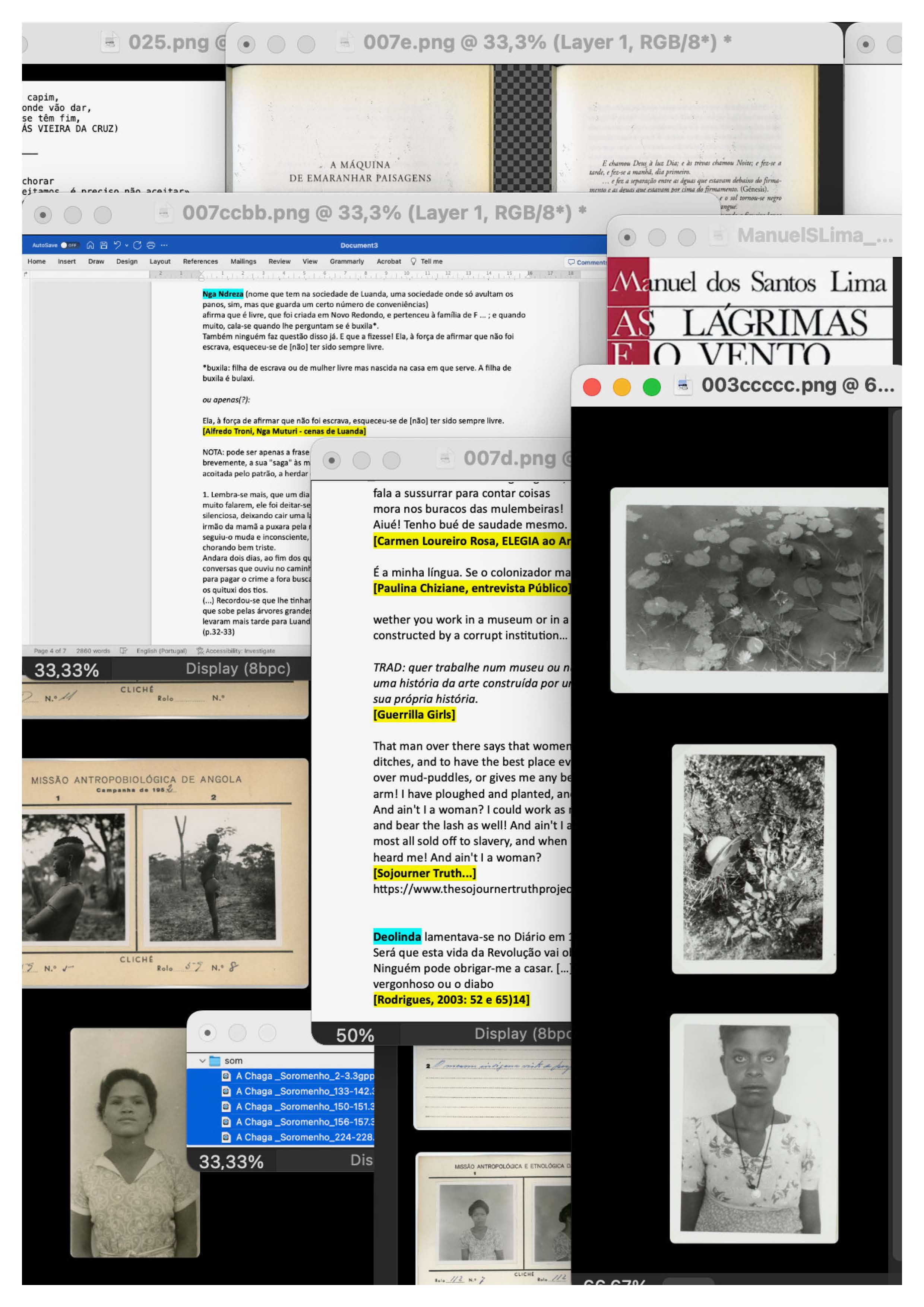

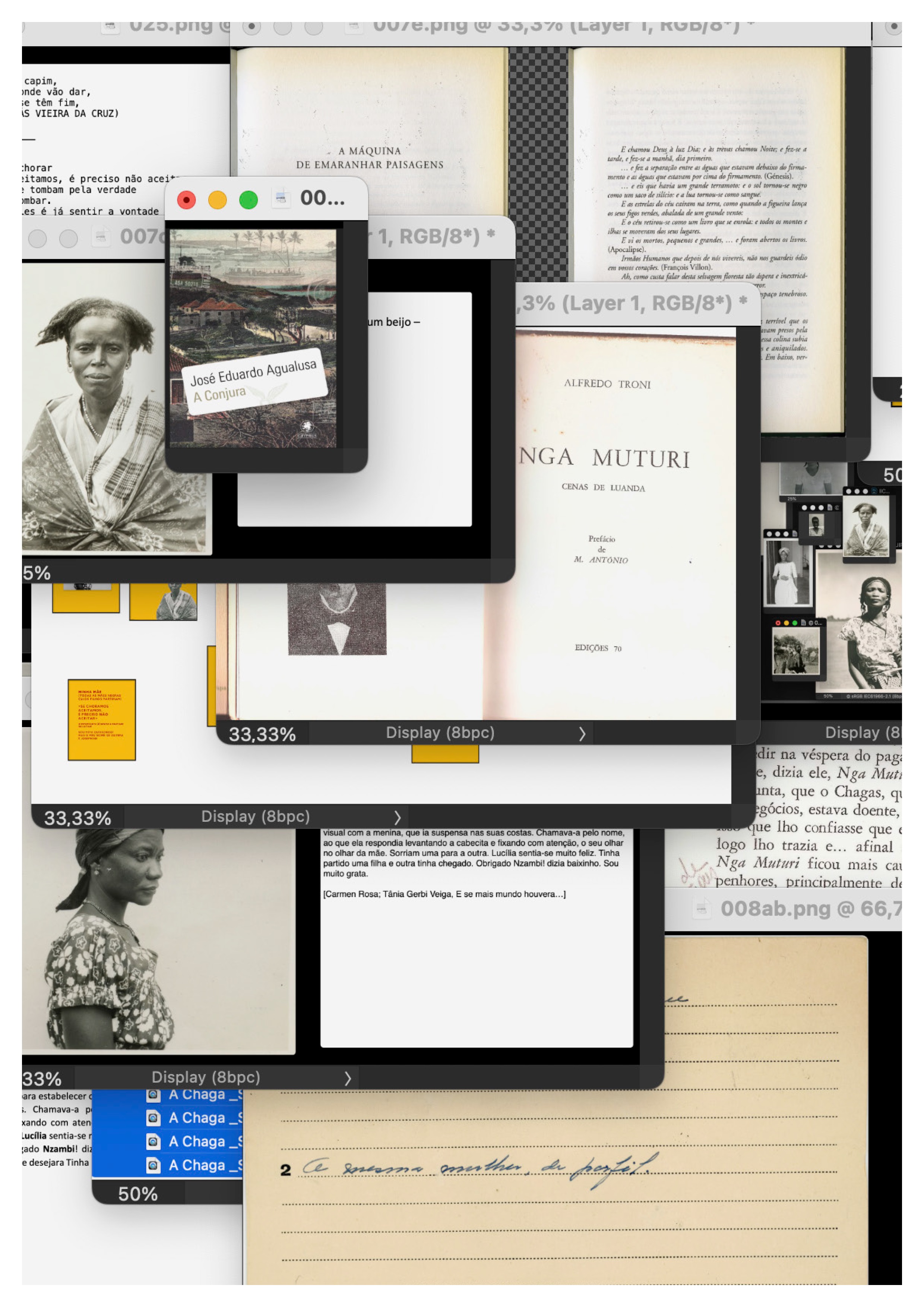

The work showcased in the exhibition was the result of an extensive process of dialogue, reading, and exchange of references, including books, poems, song lyrics, and both online and offline content. This somewhat informal exploration aimed to generate ideas and solutions. The authors engaged in lengthy conversations and underwent numerous trials, errors, detours, and encounters before arriving at the final form of the work. Portraits of women were selected from the photographic archives of the Portuguese anthropological surveys in Guinea Bissau, Angola, and Mozambique. These images were extracted from their original formats, such as cards and albums, reframed, and paired with a text in which Carmen Loureiro Rosa skillfully interweaves poetic references from her personal journey as a Black woman residing in Lisbon deeply influenced by her childhood in Angola.

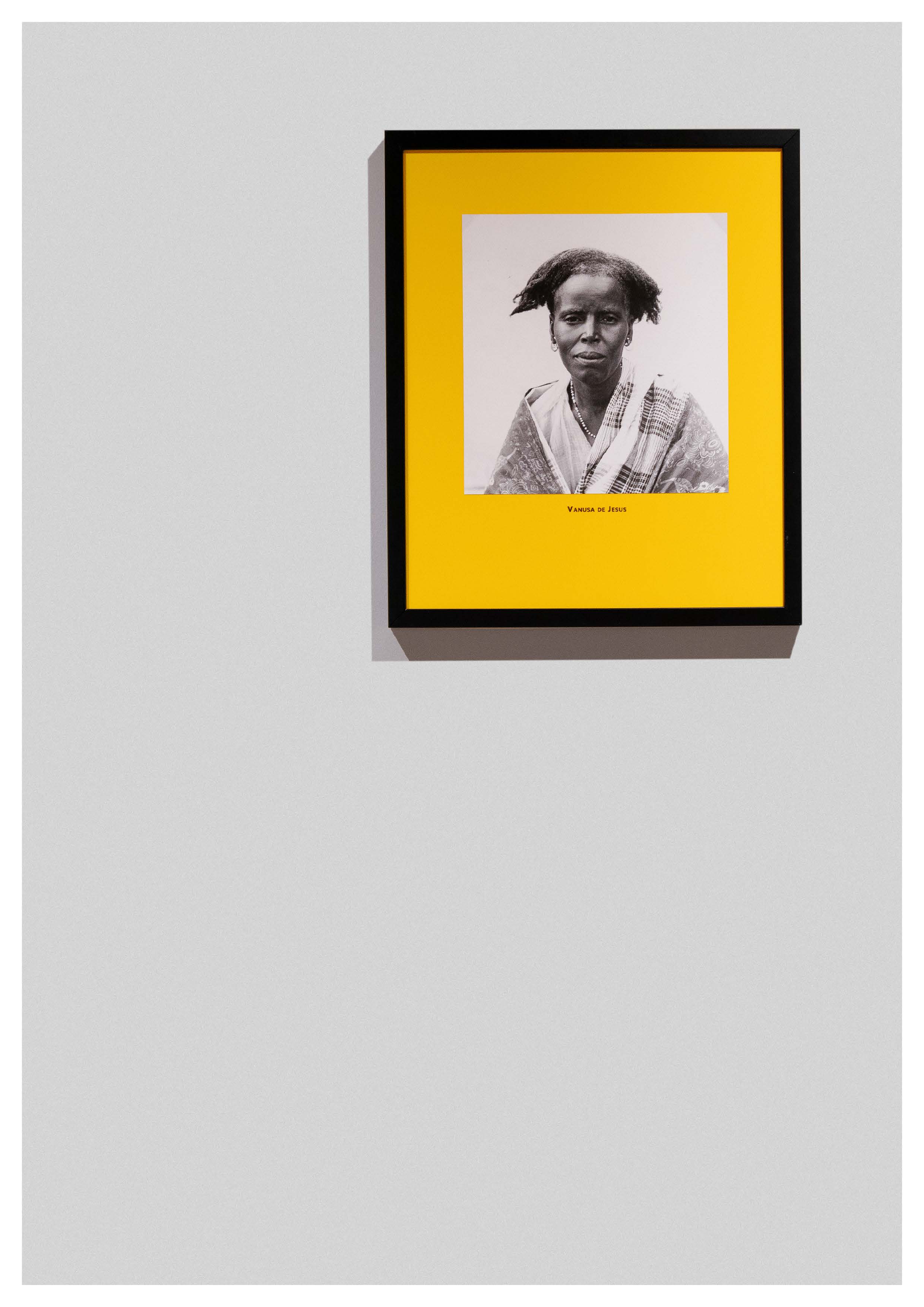

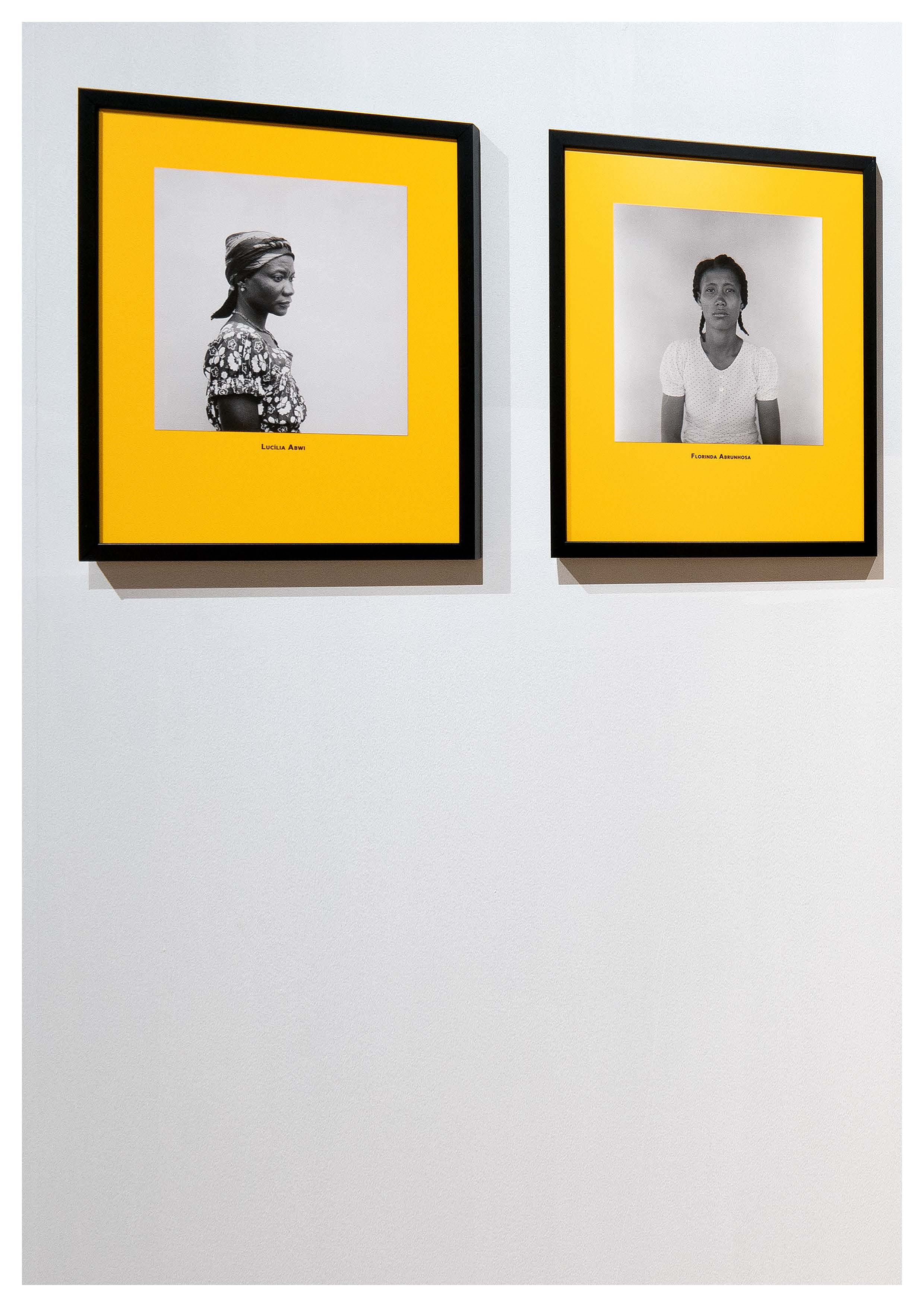

These are portraits of women whose gaze immediately captivated us, resonating with our own experiences and identities. Women whose identity and individuality we felt compelled to affirm - recognising that they were denied this recognition within the archive - by choosing to (re)name all but one of them: Messudi Camará, whose real name was one of the few documented on the photographic forms, was discovered during the working process.

Carmen Loureiro Rosa bestowed names upon some of the women, such as Njaya, Ndreza Muturi and Caninguili, drawing inspiration from fictional characters found in Angolan and Mozambican literature, of which she is an avid reader. Others bear popular Angolan names such as Masoxi, Tchissola, and Vanusa.

Carmen Loureiro Rosa also reclaimed names from her emotional past, such as Malamba, her younger brother's "home" name, born amidst the Angolan civil war, signifying "suffering" in Kimbundu. She also sought to pay homage to certain real women, such as Deolinda (Rodrigues), an Angolan guerrilla fighter, and Josephine (Baker), an artist.

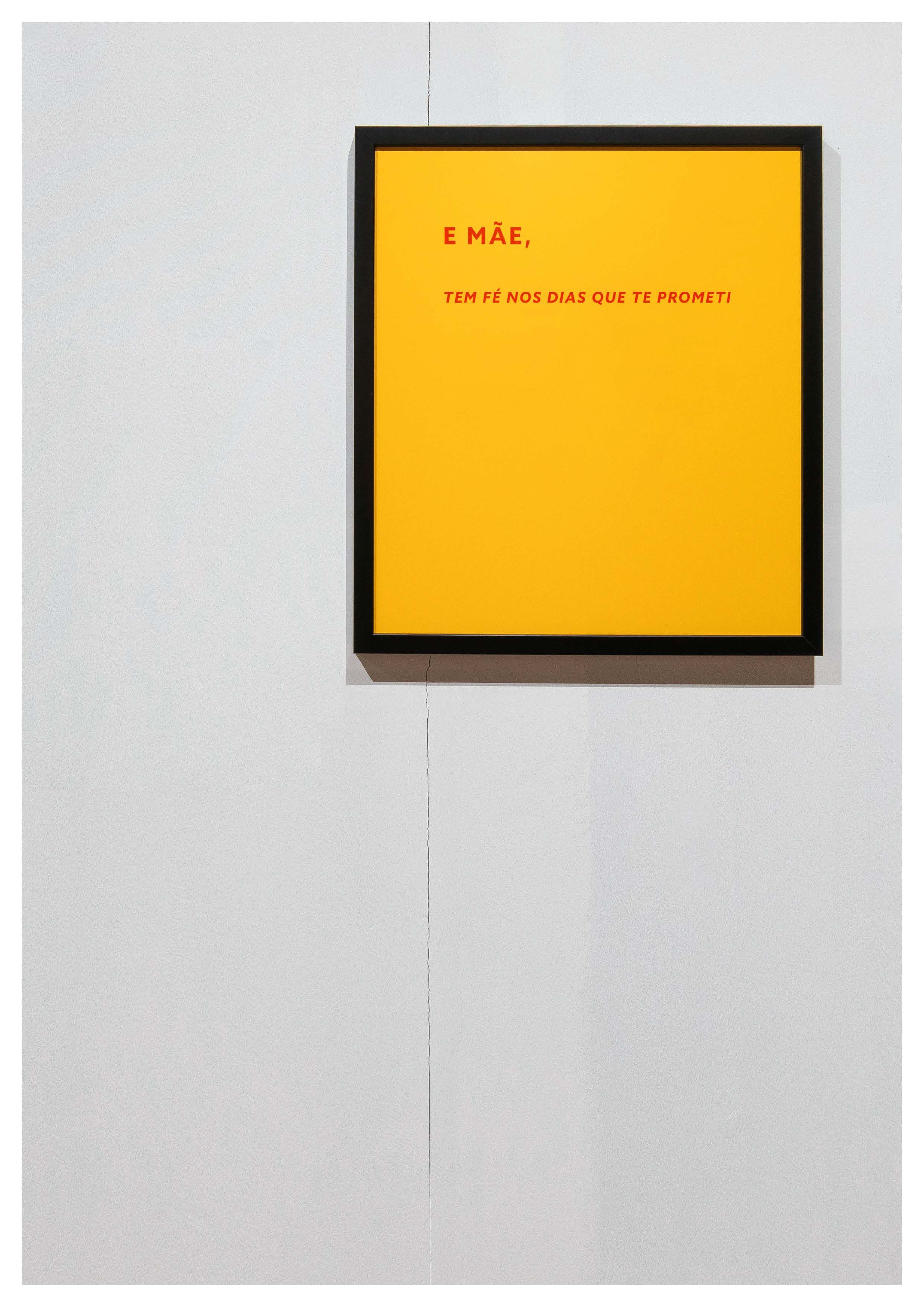

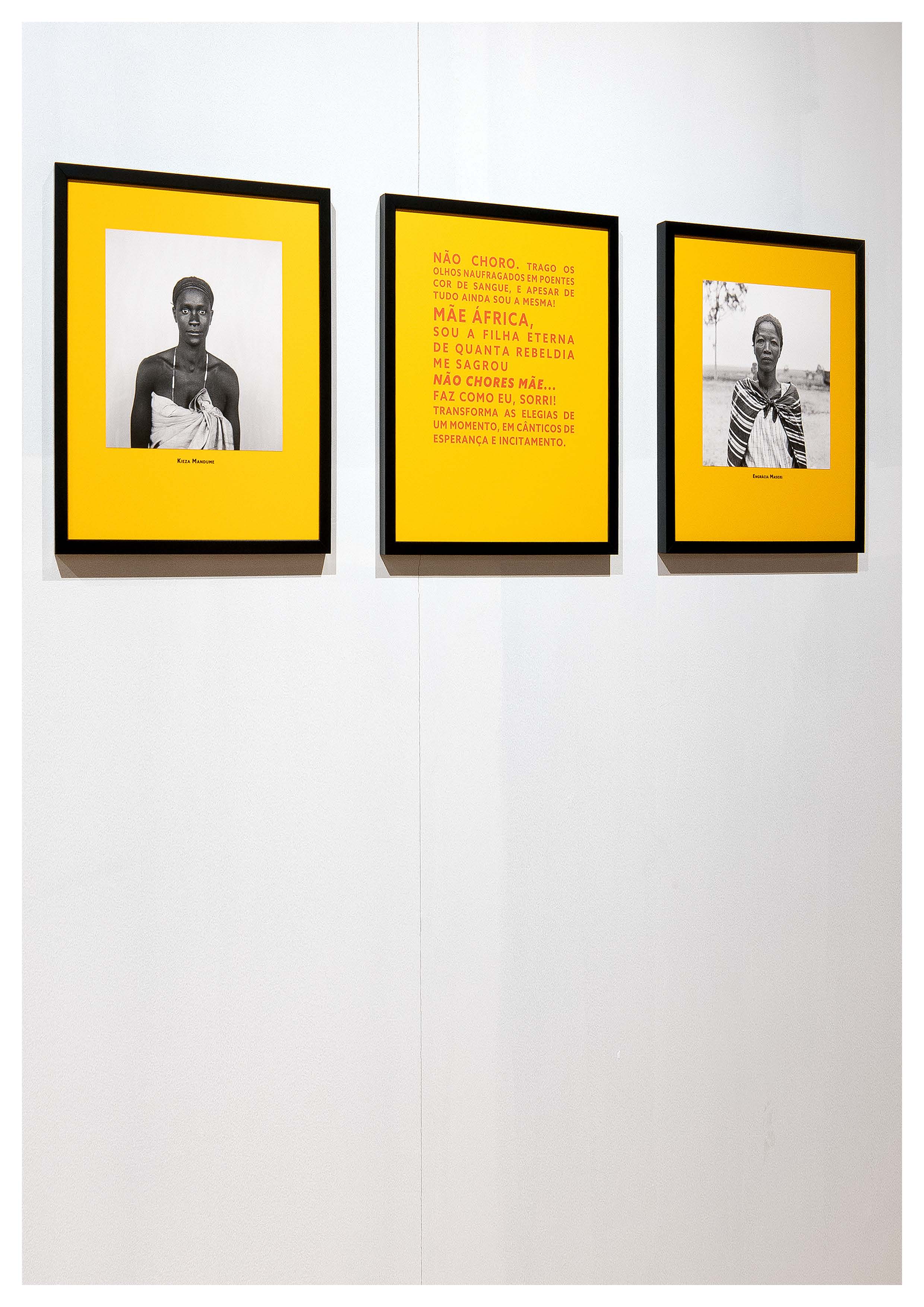

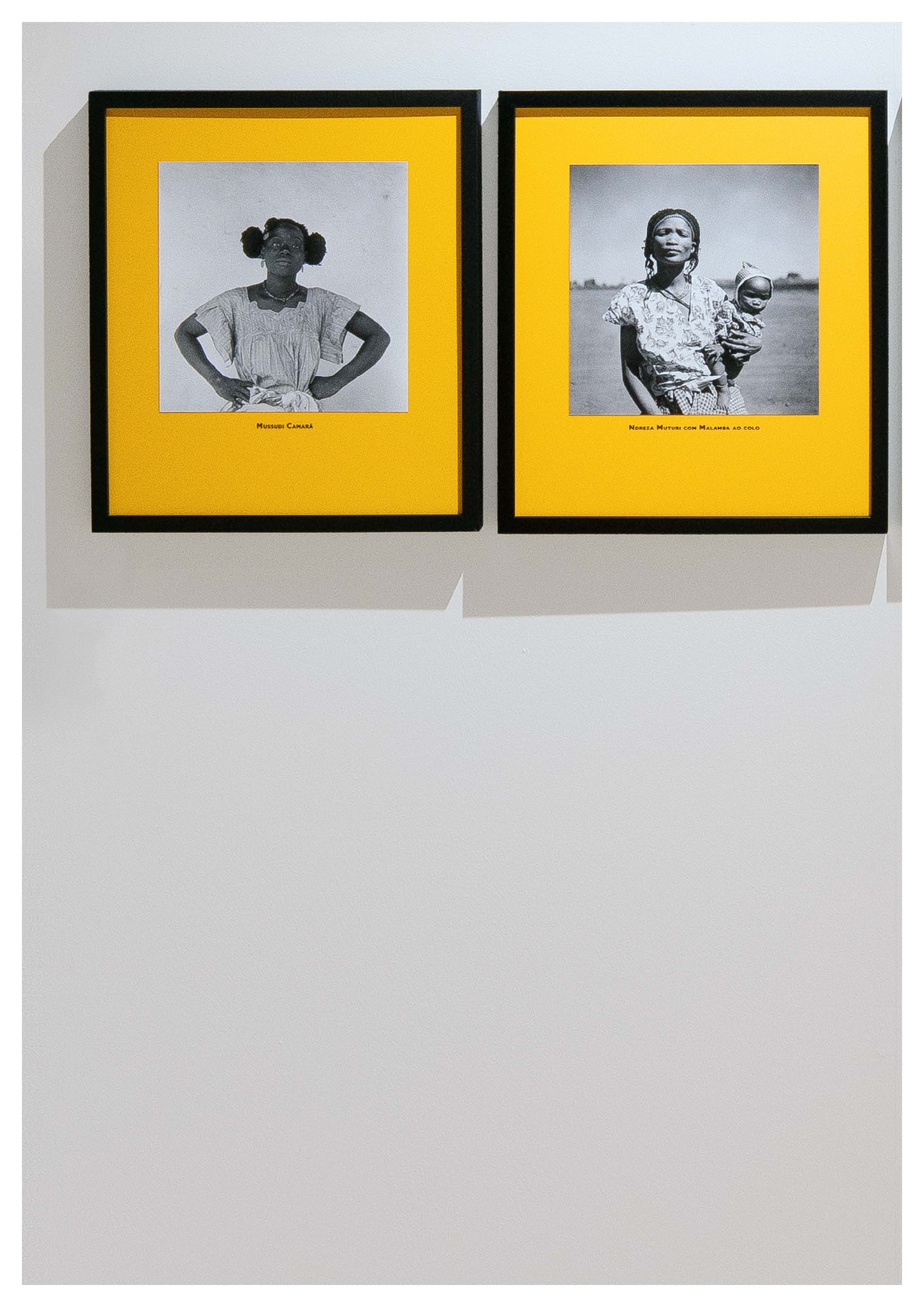

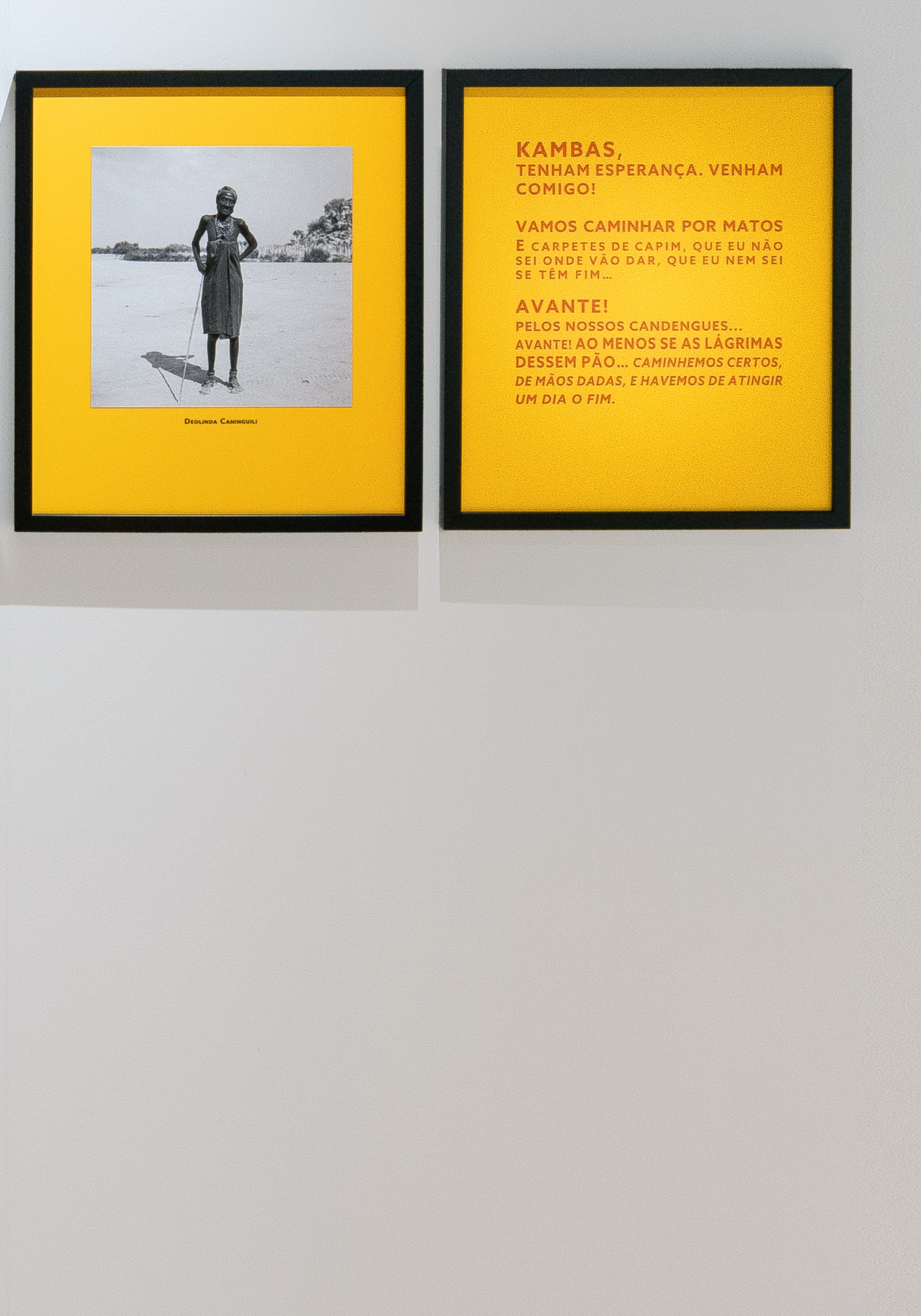

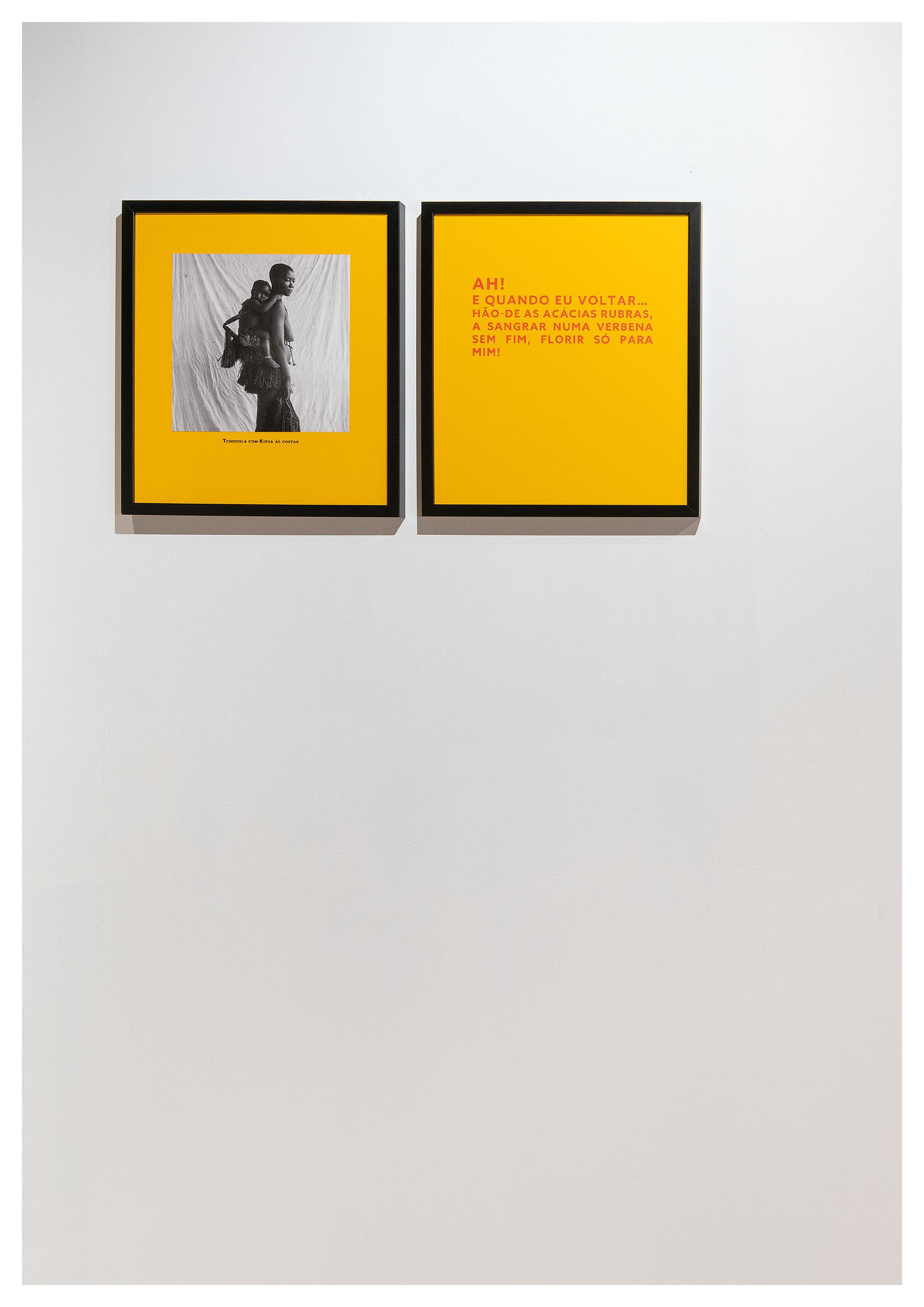

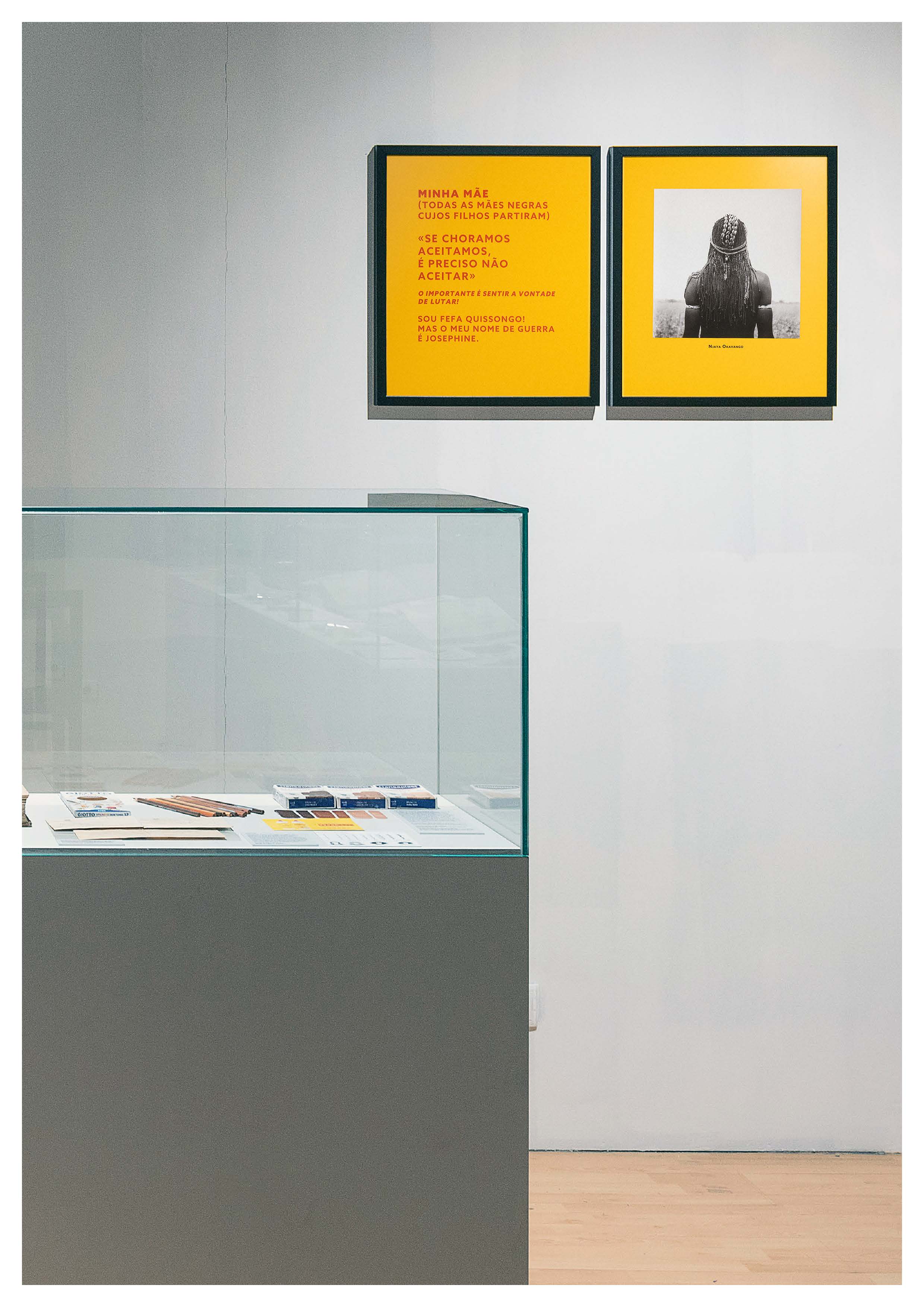

The exhibition showcases 16 framed yellow PVC panels, comprising 11 original portraits accompanied by names (either original or fictionalised) and five sections of text composed by Carmen Loureiro Rosa.

Throughout the historical period covered by the exhibition, the women depicted served as a constant yet often invisible presence. They silently observed and were frequently silenced as their territories, bodies, and minds were occupied (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). In a bid to maintain consistency with the adopted strategy - cut and paste - and to render the dialogue between the authors transparent, the images are now juxtaposed with texts that contemplate the images and prompt viewers to engage in reflective thought alongside the visuals. We anticipate that this approach will transform the images into thought-provoking entities.

Soraya Vasconcelos, 2023 (from a photograph by João Paulo Serafim, 2022)

Figure 1: VANUSA DE JESUS [without subtitle in the original] MAM, 1955-56. Santos Júnior [attrb.], Mozambique. INV. No. UL/IICT-MAM-ALB-XX_004

2. "It's Urgent to React and Act", Carmen Loureiro Rosa

I'm Black, born in Angola, and have lived in Portugal since 1979. I'm a senior civil service technician. I say this because these references help me understand the position from which I am speaking. I've lived in Europe for decades, and I see myself as privileged because I've been able to study and find employment without facing complete disenfranchisement and subalternity.

For a long time, being a woman meant being silenced. We weren't heard or seen. And invisibility was and still is a powerful means of subjugation. We lived, and sometimes still do, the silence of the oppressed - the subdued, the unseen - to which we surrender ourselves because we thought it was simply the way it was. We believed it had something to do with our fate since having another life seemed impossible. Even within civil rights movements, being a woman wasn't deemed a significant aspect of our i d entity. We didn't have the status of an autonomous, empowered individual, and we didn't even remember (or never even heard of) having ever had it. We transitioned from our father's authority to our husband's, we traded our father's name for our husband's name, and we moved from our father's house to our husband's house. In short, we always had an owner.

In colonial settings, there were also figures like the boss, the foreman, the soba, the chief of the post, and others. We were born and raised immersed in a sexist and as racist social environment that left a lasting imprint on our minds, conditioning us and causing us to undervalue our status as women. We began to perceive "race" as the only relevant identifying factor.

As I mentioned, I'm speaking from my standpoint as a Black woman. This racialsocial location is often confused. Even among us women, despite the common points of struggle, we don't all start from the same position, even among Black women, because aspects of social distinction, education and economic power carry significant w eight. But despite all this, being Black almost always means theorising from the notion of belonging to the periphery, if not the margin. The naturally authorised places of speech are usually those of "Western" hegemony.

Hence, it falls upon us if we want to free ourselves, reject this place that has been stipulated as ours, and work hard, with determination and courage, to get out of it, both materially and symbolically. Because we also know that, for the sake of the comfort and peace of mind of so many, it's in their best interest that we remain victims of poverty and ignorance so that both gender and "racial" subalternity can be maintained. We are at the bottom of the pyramid, and we have to fight and work to get out of that position. Being in that position cripples and crushes us. We urgently need to react and act. Be aware of our rights. Demand respect and dignity (Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6).

João Paulo Serafim, 2022

Figure 4: LUCÌLIA ABWI - Cabinda Woman [original subtitle] MAA, 1950. n.a., Cabinda, Angola INV. No. UL/IICT-MAA 34453; FLORINDA ABRUNHOSA - Celestina Akes/Alves(?), Catió's wife, daughter of a Chinese father and mother Papel [original subtitle] MAEG, 1946. n.a., Catió, Tombali, Guiné-Bissau, INV. No. UL/IICT-MAEG 31553

João Paulo Serafim, 2022

Figure 5: KIEZA MANDUME - Kanhemba Woman [original subtitle] MAA,1952. n.a., Mengange, Angola, INV. No. UL/IICT-MAA 34784; [TEXT]; ENGRÁCIA MASOXI - Kassekele Woman from Cazama [original subtitle] MAA, 1955. n.a. Cazamba, Angola, INV. No. UL/IICT-MAA 35532

3. Repairing Colonial Violence Against Women: Can the Photography of a Subaltern Body Speak?, Teresa Mendes Flores

"Here, I will focus on a figure who intended to be retrieved, who wrote with her body. It is as if she attempted to 'speak' across death by rendering her body graphematic" (Spivak, 1988/2021, p. 17).

Spivak (1988/2021) opens her seminal essay Pode a Subalterna Tomar a Palavra? (Can the Subaltern Speak?) with this statement. In this essay, the author begins with the extreme event of the suicide of Bhubaneswari Bhaduri, a young woman aged "sixteen or seventeen", which occurred in Calcutta in 1926. Through this act, the young woman intended to assert her anti-colonial political position, specifically against British colonialism in India. However, at the time of the incident, this message was not understood because it was "written" using codes unimaginable for a young woman; it "had been a letter in the alphabet of the discursive transformation" (Spivak, 1988/2021, p. 17). A revolutionary, emancipatory alphabet deemed inappropriate for women and consequently largely withheld from them.

The political interpretation of Bhubaneswari Bhaduri's "graphematic body" only surfaced 10 years later when a letter she had left for her elder sister was unveiled. In it, she recounted her involvement in a liberation movement and the struggle for her country's independence. "She had been entrusted [by the members of the group] with a political assassination. Unable to confront the task and yet aware of the practical need for trust, she killed herself" (Spivak, 1988/2021, p. 126).

What the essay goes on to discuss, delving into the theoretical legacies of Marxism and Western post-structuralism, is, on the one hand, the exemplary nature of this gesture as evidence of trust towards the members of her group and, simultaneously, an act of courage, resistance and (paradoxical) affirmation of existence (and the right to exist); and, on the other hand, the failure of this act, given the inability to read this suicide at the time it occurred: "suicide, in general, poses itself as enigma" (Spivak, 1988/2021, p. 126); "she 'spoke,' but women did not, do not, 'hear' her" (p. 17). In light of this failure, the question arises: "can the subaltern speak"? Can she really "take the floor"? What are the conditions for her to speak and truly be heard?

The interpretation of suicide is particularly complex in India due to the tradition of the "good wife", the ritual of Sati, involving the self-immolation of widows on the funeral pyre of their deceased husbands, which holds significant implications for this case. As the young woman was unmarried, the act was deemed unjustified unless she was pregnant. However, as Spivak (1988/2021) elucidates, the young woman deliberately chose to end her life while menstruating to negate this interpretation. Consequently, there were no acceptable codes to elucidate the event except for its suppression and erasure, which Spivak's essay unearths and restores.

***

It was only recently that this story and these reflections echoed in my mind to consider the work Mulheres Sempre Presentes (by Rosa, Vasconcelos and Mateus, 2022). This project seeks to restore dignity and agency to a collection of portraits of Black women subjected to oppressive "photographic operations" intended to transform them into specimens of "racial types" (Edwards, 1990; Poole, 2005). We are referring to the photographs produced by Portuguese anthropo-biologists during the anthropological surveys conducted between 1936 and 1975 in what were then Portuguese colonial possessions in Africa and Asia.

How can the photographed bodies speak? - This question has always underpinned our experience of these images and the research we have conducted on them. Now, with some distance from the collective discussions that led to this work, Spivak's (1988/2021) essay illuminates our reflections. It seems to amplify the questions regarding the status of subalternity and the possibilities of speech, and, maybe just as important as the ownership of the word, the importance of listening: being heard and taken seriously.

How can these mute images speak? How can they, today, here and now, compel us to speak? How can they remain silenced even as they speak? Who are these women, staring at us from the foreground of the image - depicted so clearly and in such close-up frames? What were they compelled to say? And to silence?

Throughout the research process, we often felt like Pandora, opening her box and releasing "evils into the world", stirring dormant ghosts. These ghosts haunted us, particularly as we committed to holding a final exhibition of the project.

We quickly confronted the problem of reproducing negative stereotypes about Black people. Would we exhibit these images reproducing stereotypes? Exhibiting implies giving attention and, almost always, magnifying and praising, which requires an awareness of the politics of visuality at play. We understood that we were engaging with image practices that were part of a broader range of procedures perpetuating, now under the legitimising guise of "scientificity", the long-standing cultural construction of "Blackness", and that this construction had little to do with Black people regarded merely as its "objects". On the contrary, these images spoke volumes about their producers, the "measuring" scientists, although they concealed the fact that they represented a perspective: that of Whiteness (Fanon, 1952/2017; Thuram, 2020/2022).

Said (1997/2004) has extensively demonstrated how "Orientalism" was an invention of Western thought, just as White thought (Thuram, 2020/2022) created "Blackness". We are all (still) in the same boat, albeit heirs to different places in it.

Thus, the exhibition could only have any real meaning if it engaged with diverse perspectives on this same history, encompassing various subjectivities socially constituted through these contrasts. In line with various museum decolonisation practices (German Museums Association, 2018; Golding & Modest, 2013; Odumosu, 2020; Vergès, 2023; Vlachou, 2022), the exhibition was developed through participatory and collective curation.

***

Operators, Spectrum, Spectators

The Portuguese colonial physical anthropology (or anthrop-obiology) surveys, led by medical anthropologists from the Anthropology Institute of Porto, photographed thousands of non-White people using the visual grammar proposed by Alphonse Bertillon's (1890) system, known as "bertillonage", originally designed for criminal identification. Along with numerous body measurements (the form used by the Portuguese surveys indicates around 60 measurements), photographic records were to be added to facilitate the identification of criminals.

Each individual was photographed twice against a "neutral" backdrop. One of the photos was taken with the subject facing the camera, the other one in profile, maintining a serious expression with their arms aligned alongside their body. In a frontal portrait, a slightly oblique orientation of the head was recommended to make one of the ears visible and avoid distortions caused by the nose. The lighting should be bright to eliminate shadows. Closer frames were employed for specific purposes, such as capturing tattoos or specific features. Full-body and rear shots were also possible (Bertillon, 1890).

The goal of the criminal identification files, structured within the archive according to typified physical traits (such as head shapes, nose types, ear forms, etc.), was to recognise repeat offenders, deemed exemplary cases for studying crime and its roots. The theory of a biological basis for crime was under examination within the framework of heredity studies, tracing back to Lamarck and Darwin, and partly adopted by eugenics (from eu-good, genes-generation), a branch of biological science aiming to control (or even eradicate) individuals with "bad genes" believed to cause degeneration within the human species.

The practice of depicting images has its earliest roots in scientific illustration, a field that began evolving in Europe during the Renaissance. It was closely linked to the emergence of the natural sciences as observational disciplines and, subsequently, to the field of natural history.

Applying Bertillon's system to colonial anthropology represented a small step. This application was justified by the assumption that the human species encompasses various "races" and that those races not belonging to those of the White biologically inferior, should be assigned a social position that best suited their natural traits to be more beneficial to society.

Understanding their physical features, which were believed to influence "the Indigenous mentality", their behaviour, and social organisation, was seen as beneficial for both colonisers and the colonised, on behalf of a (supposed) scientific and modern colonialism that was portrayed as fully happy and fair. It seemed as though the colonisers were bestowing a favour upon the colonised people! A phenomenon well known in psychoanalysis as "inversion" (Fanon, 1952/2017; Kilomba, 2008/2019).

The photographic images of the anthropological surveys thus represent an institutional operation, signifying the imposition of a colonial identity based on membership in an ethnic group perceived as physically distinct from others.

The bodies were forced to speak.

The photographic system produced their speech, organised - through its grammar - its system of negative differences. It imposed an order on the photographed subjects, aiming to expose their "disorder", their "deviation" from the perceived norm. These repetitive series of photographic records, generating comparable visual data from extensive (presumably representative) population samples, were archived and categorised as specimens, forming the scientific object and functioning as an inventory of degenerates.

The curatorial group responded to these interpretations. We identified various forms of resistance from the subjects themselves, whether conscious or not: bodies that did not conform to Bertillon's system and did not comply with the prescribed pose. Gazes that did not submit, that resisted. Women would not let go of their children, still babies or very young (and the children were of no interest to anthropometrists).

Despite the readings imposed by the codified system, the photograph, being indicative, captures the entirety of the subject: the women and men present their identity in its completeness. Their bodies, attitudes, and expressions speak to us and resist the apparatus. Their photographically mediated presence (Edwards, 2021) has reached us. How can we honour it?

This presence needs to be politicised, understanding what these bodies convey and establishing a space for listening to become possible. The colonial project has achieved numerous erasures: something has been irreversibly lost.

The utter silence of these images also lies in the fact that most of us are unable to read them (just as the Indian community was unable to read Bhubaneswari's suicide).

From this colonial anthropology, we glean no information about the political systems, economic structures, religious practices, or beliefs of the individuals captured in the photographs. There was also a tendency to reduce cultural practices to ethnographic folklore in order to exhibit them in a museum (objects perceived as on the brink of extinction and therefore worthy of preservation).

While photography's indexical nature is a form of objectification and evidence, the operator cannot fully control it (Barthes, 1980/2008). There are always imponderables, overlooked details, and interstices.

Deborah Poole (2005) highlights the challenge of creating "types" through photography, noting that photographs inherently contain an "excess of description". Similarly, Patricia Hayes suggests that photographs are "ambivalent" (Hayes & Minkley, 2019), resisting absolute fixation of meaning.

Photography is indomitable (as Barthes said).

Many of the women portrayed (Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, and Figure 13) resist the "bertillonage" system through their posture; some even defy the camera. We recognise faces and bodies that demand the restoration of their erased personal histories, challenging the status of subalternity and colonisation with which they refuse to identify themselves (similar to the case of young Bhubaneswari Bhaduri).

João Paulo Serafim, 2022

Figure 9: MESSUDI CAMARÁ - Nalu Woman from Capeane - Cacine [original subtitle] MAEG, 1947. n.a., Capeane, Cacine, Guiné-Bissau INV. No. UL/IICTMAEG 31588; NDREZA MUTURI WITH MALAMBA ON HER ARMS - Mukankala Woman, from Capelongo, Quipungo [original subtitle] MAA, 1955 campaign. n.a., Capelongo, Angola INV. No. UL/IICT-MAA 35725

João Paulo Serafim, 2022

Figure 10: DEOLINDA CANINGUILI - Mucuissi Elderly Woman [original subtitle] MAA, 1955. n.a., Angola INV. No. UL/IICT-MAA 35609; [TEXT]

João Paulo Serafim, 2022

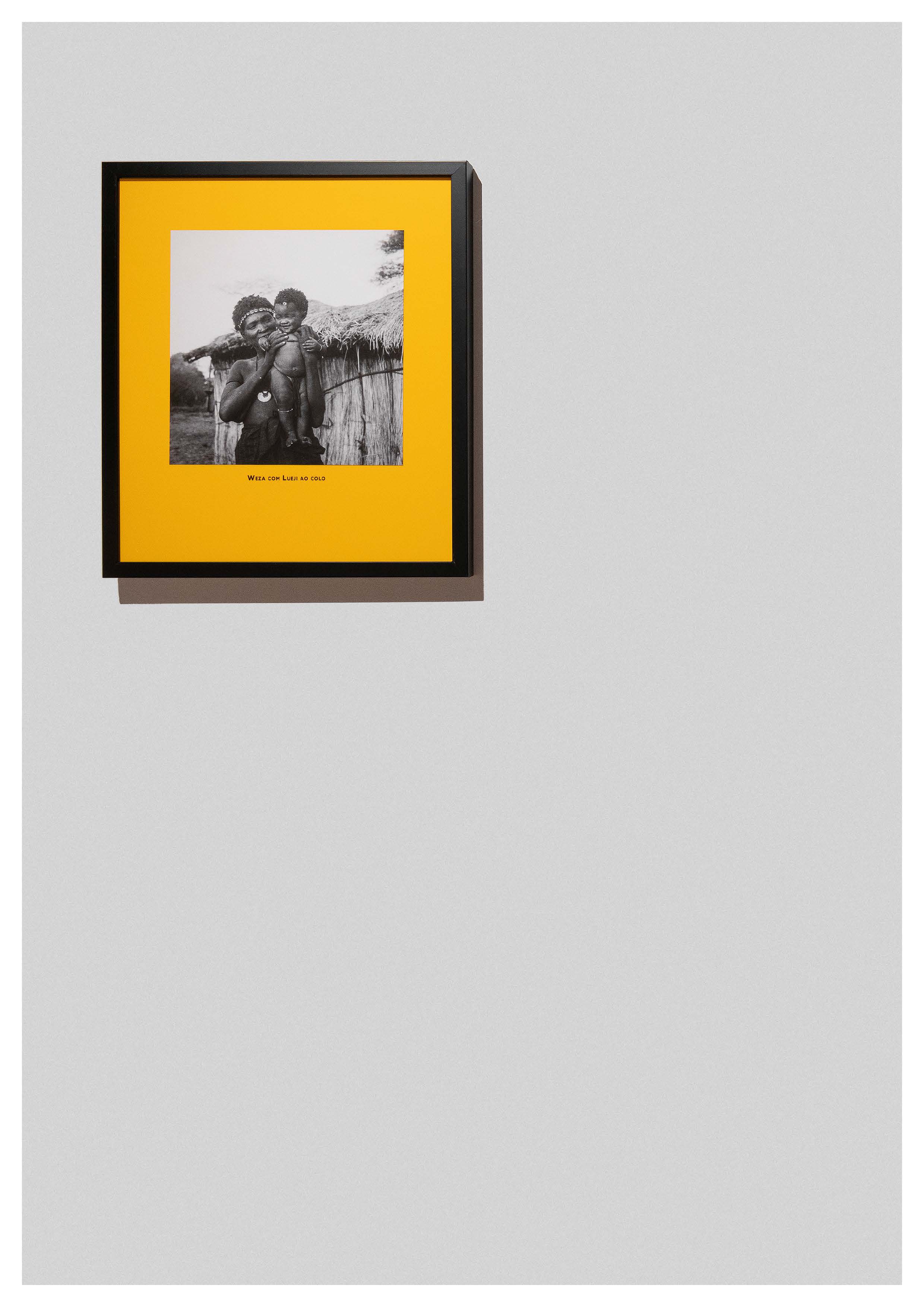

Figure 11: TCHISSOLA WITH KIZUA ON HER BACK - Woman carrying her son. [original subtitle] MAEG, 1946. n.a., Ilha de Uracane,Guiné-Bissau INV. No. UL/IICT-MAEG 26419; [TEXT]

João Paulo Serafim, 2022

Figure 12: [TEXT]; NJAYA OKAVANGO - Kan-hemba woman's hairstyle [original subtitle] MAA, 1952. n.a., Mucusso, Cuando-Cubango, Angola INV. No. UL/IICT-MAA 35385

4. Note on the Archive: Where Do the Images Take Us?, Catarina Mateus

This work stemmed from a fact brought to light during discussions about the exhibition that the vast majority of the portraits were unidentified. In fact, there are thousands of portraits devoid of a name, a personal identification of each individual, replaced by a typification, classifying people based on ethnicity or cultural group, in some cases through the attribution of a presumed stigma, such as a tattoo, scarification, or the intentional dental modification (referred to in the archive as dental mutilation). It was further noted in the discussion, for added precision, that this pattern was particularly evident in the anthropological surveys to Angola and Timor, led by António de Almeida and Mozambique, led by J. R. dos Santos Júnior. It was observed to a lesser degree in the anthropological and ethnological surveys to Guinea, under the leadership of Amílcar M. Mateus, where some of the portraits are identified by name, either written on the back of the print or the back of the photographic form.

No records were found in the archive about the reason for the absence of identity: during discussions, speculation arose that this might be attributed to work methodologies (names were excluded in medical observations for statistical purposes) or the primary objective of each survey (studying populations from a bio-ethnic perspective was the main focus; Decreto-lei 34478, 1945); or even the personal interest and varying degrees of sensitivity among the anthropologists leading the campaigns (despite their adherence to the guidelines of Mendes Correia, director of the Anthropology School of Porto). Another notion considered was the challenge of writing or understanding names in the individuals' native languages. Without concrete evidence, it is challenging to draw definitive conclusions. However, irrespective of the methodological choices or the reasons behind this anonymity, the fact remains that the majority of individuals photographed during the colonial anthropological surveys merely "existed" as a female or male type or belonged to an ethnic group that was often labelled Western terms - for example the Khoisan were referred to as "bosquimanos" (men of the woods) - or sometimes without any identification at all, as seen in the photographs from the Mozambique Anthropological Mission.

This fact impresses and disturbs anyone who delves into the archives. It is also linked to the broader context of a study assumed to be discriminatory, classificatory and above all political, promoted by the Portuguese government, given the urgent effective occupation of the territories and the "civilising action" extensively promoted through propaganda.

The archives of the anthropological campaigns, materially represented by documents, photographs, reports, notes and field diaries, are not static. They have their own path - their biographical and custodial history - from their creation to the present day, which is not always easy to trace. Their organisational logic (or lack thereof) is not always easy to understand. The connection or dispersal of documents - which occurs for numerous reasons related to their use - and the human tendency to classify, organise, fragment, or associate in order to create useful communication codes (it should be noted that documents are not always considered "archives" by those who produce or maintain them, nor are they always systematically managed by professional archivists) sometimes lead to a jumble of information and, consequently, more or less reliable interpretations of the facts.

It is important, therefore, to remain open-minded when a more interpretative or artistic result emerges regarding scientific archives. In endeavours intended to be honest, we embrace the interpretations, ambiguities, and personal upheavals we are confronted with when grappling with History and our own past. We cannot solely rely on the archive as the sole witness to the "crimes", as the history of the archive itself may be an incomplete and misleading source, at some point, of facts essential to understanding it. The archives, for reasons almost always beyond the reader's control, are not always processed or available in the timelines we set for ourselves.

In the case of the essay Mulheres Sempre Presentes we have made two mistakes in our interpretation of the handwritten notes in the documents: we have recently found the name of Celestina Akes/Alves (?) in another document, a woman who, at the time of the exhibition, remained anonymous to us. We have also rectified the name of Messudi Camará, whose handwriting on the originals caused us much doubt and led to the incorrect reproduction of her name in 2022 as "Mussudi". Perhaps this rectification was not important in an openly visual and artistic essay, but these women, whose names were taken from them in the past, deserve recognition.

Visual and editorial design by Soraya Vasconcelos based on images captured at the exhibition "O Impulso Fotográfico. (Des)arrumar o Arquivo Colonial" by João Paulo Serafim, 2022 (Figures 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 9, 10, 11, and 12); images transformed or produced by Soraya Vasconcelos, 2023 (Figures 1, 3, 6, 7, 8, and 13); and texts by Carmen Loureiro Rosa, Teresa Mendes Flores, Catarina Mateus ***

MULHERES SEMPRE PRESENTES, 2022 Carmen Loureiro Rosa, Soraya Vasconcelos, Catarina Mateus

Exhibition details: 11 inkjet-printed photographs on matt paper, adhered to yellow PVC board with name printed in black; five yellow PVC boards featuring text printed in magenta; dimensions: 30 x 30 cm (print); 44 x 50 cm (frame).

Text composed by Carmen Loureiro Rosa, based on the appropriation of excerpts from: Alda Lara ("Anúncio”, "Presença Africana”, "De Longe”, "Regresso"), Tomás Vieira da Cruz ("Bailundos"), António Cardoso ("É Inútil Chorar") e Agostinho Neto ("Adeus na Hora da Largada").

Portraits sourced from the photography collection of the Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical, affiliated with the University of Lisbon/National Museum of Natural History and Science in Lisbon: Col.Missão Antropobiológica de Angola (MAA); Col.Missão Antropológica e Etnológica da Guiné (MAEG); Col.Missão Antropológica de Moçambique (MAM).

Acknowledgements

Terese Mendes Flores was financed by National Funds through FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology under the ICNOVA UIDB/05021/2020 project.

Soraya Vasconcelas was financed by National Funds through FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology under the CICANT UID5260/2020 project.

REFERENCES

Barthes, R. (2008). A câmara clara. Nota sobre a fotografia (M. Torres, Trad.). Edições 70. (Trabalho original publicado em 1980) [ Links ]

Bertillon, A. (1890). La photographie judiciaire. Gauthier-Villars et Fils Imprimeurs Libraires. [ Links ]

Cabral, A. (1979). Análise de alguns tipos de resistência. Imprensa Nacional. [ Links ]

Césaire, A. (1955). Discour sur le colonialisme. Editions Presence Africaine. [ Links ]

Edwards, E. (1990). “Photographic types”: The pursuit of method. Visual Anthropology, 3(2-3), 235-258. https://doi.org/10.1080/08949468.1990.9966534 [ Links ]

Edwards, E. (2021). Photography and the practice of history. Bloomsbury Academics. [ Links ]

Fanon, F. (2017). Pele negra, máscaras brancas (A. Pomar, Trad.). Letra Livre. (Trabalho original publicado em 1952) [ Links ]

German Museums Association. (2018). Guidelines on dealing with collections from colonial contexts. https://www.museumsbund.de/wpcontent/uploads/2021/03/mb-leitfaden-en-web.pdf [ Links ]

Golding, V., & Modest, W. (Eds.). (2013). Museums and communities. Curators, collections, and collaboration. Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Hayes, P., & Minkley, G. (2019). Ambivalent. Photography and visibility in African history. Ohio University Press. [ Links ]

Kilomba, G. (2019). Memórias da plantação. Episódios de racismo quotidiano (N. Quintas, Trad.). Orfeu Negro. (Trabalho original publicado em 2008) [ Links ]

Odumosu, T. (2020). The crying child. On colonial archives, digitization, and ethics of care in the cultural commons. Current Anthropology, 61(22). [ Links ]

Poole, D. (2005). An excess of description: Ethnography, race and visual technologies. Annual Review of Anthropology, 34, 159-179. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.33.070203.144034 [ Links ]

Said, E. W. (2004). Orientalismo. Representações ocidentais do oriente (P. Serra, Trad.). Edições Cotovia. (Trabalho original publicado em 1997) [ Links ]

Senghor, L. S. (1992). Liberté. Tome 1 - Négritude et humanisme. Editions du Seuil. [ Links ]

Spivak, G. C. (2021). Pode a subalterna tomar a palavra? (A. S. Ribeiro, Trad.). Orfeu Negro. (Trabalho original publicado em 1988) [ Links ]

Thuram, L. (2022). Pensamento branco (S. S. e Silva, Trad.). Tinta-da-China. (Trabalho original publicado em 2020) [ Links ]

Vergès, F. (2023). Programme de désodre absolu. Décoloniser le musée. La Fabrique. [ Links ]

Vlachou, M. (2022). O que temos a ver com isso? O papel político das organizações culturais. Buala; Tigre de Papel. [ Links ]

1 The exhibition opened on December 21, 2022, and has been continually extended due to the significance the museum has placed on it. As of the time of writing, it remains open to the public. Participating in the curation (in alphabetical order) were: António Fernando Cascais, Carmen Loureiro Rosa, Catarina Mateus, Lorena Sancho Querol, José Luís Garcia, Marinho de Pina, Margarida Medeiros, Nkaka (K4PP4) Bunga Sessa, Rita Cássia Silva, Samira Amara, Sara Fonseca da Graça (Petra.Preta), Santos Garcia Simões, Soraya Vasconcelos and Teresa Mendes Flores.

2Project funded by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia under number PTDC/COMOUT/29608/2017: The Photographic Impulse: Measuring the Colonies and the Colonial Bodies. The Photographic and Filmic Archive of the Portuguese Geographic and Anthropologic Missions.

3We mention some of them: Lima (1975/2005); Pepetela (1996/2008), Soromenho (1964/1985); Troni (1882/1973); as well as unpublished texts by Carmen Loureiro Rosa ("A 4º Classe", "A Tia Maria", "Elegia ao Arco Iris", "Luanda Novo Redondo e Lobito" and, with Tânia Gerbi Veiga, "E Se Mais Mundo Houvera...").

4An essential formal reference for this approach was the poem "A Máquina de Emaranhar Paisagens" (The Machine of Tangled Landscapes) by Herberto Helder (2014).

5Text adapted from the presentation at the "IV Visual Culture Meeting - Reparations", Sopcom, June 24, 2023, Mala Voadora, Porto.

6In the course of emancipatory social processes, concepts of identity and social positions, initially defined negatively by hegemonic powers as tools of control, often become focal points for positive redefinitions and resignifications by the groups to whom these concepts and positions were originally ascribed. Thus, the concept of "Blackness" - and its intersections of class and gender - has been central to the positive affirmation and emancipatory practice of these groups and individuals (Cabral, 1979; Césaire, 1955; Senghor, 1992). In this passage, we refer specifically to the hegemonic historical construction of the concept of "Blackness" by "White thought", which considers itself universal and normative and consequently fails to reflect on its own position.

7The following missions and campaigns were conducted: Anthropological Mission of Mozambique, 1936, 1937/38, 1945, 1948, 1955/56 campaigns. Anthropological and Ethnological Mission of Guinea, 1946 and 1947 campaigns. Anthropo-biological Mission of Angola, 1948, 1950, 1952 and 1955 campaigns. Scientific Mission o f São Tomé (Ethnosociology Brigade of São Tomé), 1954. Anthropological Mission of Timor, 1953 to 1975 campaigns.

Received: December 19, 2023; Revised: February 16, 2024; Accepted: February 16, 2024

text in

text in