Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista Diacrítica

Print version ISSN 0807-8967

Diacrítica vol.27 no.3 Braga 2013

Traces of Portugal in Bollywood

Vestígios de Portugal em Bollywood

Francisco Veres Machado*

*For the last ten years, Francisco Veres Machado produced and presented TV documentaries and series, mostly shot in India and Southern Europe for RTP, Belgian television and the Indian channel Prudent Media. He holds an M.A. in Critical Media and Cultural Studies from University of London, SOAS - School of Oriental and African Studies. CREDITS OF A FIRST DRAFT PREVIOUSLY PUBLISHED: A first draft of this paper was publish in the film Magazine Celluloid nº 34, January 2013, by Rainbow Film Society – Dhaka, Bangladesh. Ahmed Muztaba Zamal on behalf of Rainbow Film Society authorised its reprint.

ABSTRACT

In order to explain how Goan musicians merged into Bollywood film industry, certain historical and organizational facts are revisited, weaving a connection between educational options under Portuguese colonialism, migration between Goa and Mumbay, the jazz bands of the Roaring Twenties and Bollywood music industry.

Keywords: Goan musicians; Bollywood; Goan emigration.

RESUMO

A fim de explicar como se integraram músicos goeses na indústria cinematográfica de Bollywood, certos factos organizacionais e históricos são recuperados, tecendo-se uma relação entre as opções educativas oferecidas pelo regime colonial português, a emigração entre Goa e Mumbai, as bandas de jazz dos anos 20 e a indústria das bandas sonoras dos filmes de Bollywood.

Palavras chave: Músicos goeses; Bollywood; emigração goesa.

From Bombaim to Mumbai

The very first and immediate bind between Bollywood films and such a remote European country like Portugal is the old name of the city Bombay that establishes the location from where Bollywood films are produced.

One of the possible etymologies for the word Bombay is a corruption of a Portuguese archaic expression meaning good little bay or Bombaim, which the British later adopted as Bombay.

After 1947, when India became independent, the development of identity struggles, in most states of the Indian Union, led them to a passionate replacement of monuments and names, mainly those that were in anyway related to the past colonial rulers. Subsequently, in November 1995, the city of Bombay was officially renamed as Mumbai.

This little story of Bombays etymology is loaded with side information, which is worth addressing in order to better understand how it is not surprising to find, in the origins of the Bollywood films, traces of what were once strategic ports of the Portuguese Colonial Empire, Mumbai and Goa.

Mumbai was part of a Portuguese princess dawry

More than 100 years before the arrival in India of the French, Dutch, Danish, and British, the Portuguese occupied Diu, Daman, Kochi, Bombaim and Goa. The latter was in fact the very first colony of the whole European eastern expansion, conquered by Portuguese sailors in 1510. With this network of strategically placed ports, Portugal gained trade and military control of the whole Indian Ocean along 16th and 17th centuries.

British first step into Indian territory happened only in 1661, as a direct result of the marriage of King Charles II of England with the Portuguese princess Catarina de Bragança. Mumbai, or Bombaim as it was called then, was part of the princess dowry, as well as Tangier, in North Africa, plus 300,000 pounds, which Portugal paid only partially in cash and the rest, due to lack of funds, was substituted by boxes of tea.

After losing Mumbai to the English crown, Portugal ruled its Indian colonies for near five centuries, until December 19th 1961, when Indian troops conquered the three remaining Portuguese enclaves of Goa, Daman and Diu. These were the last territories to be integrated in the Indian Union map, the way it is outlined until the present day.

The two Empires, the Portuguese and the British, had significant differences, geographically, politically, socially and economically, but for the matters concerned here, it is particularly worth tackling differences in the educational system in order to explain how Portuguese musicians merged into Bollywood film industry.

Why Portuguese artists instead of English musicians?

Why not other western artists, such as English musicians, since at the time that Bollywood was giving its first steps, Mumbai was a vibrant metropolis of the British Empire? – Lets go back to Portugal during the first years after World War I.

The limited offer of higher education in Portugal

In the beginning of the 20th century, Salazar, the Portuguese fascist dictator, who was in power from 1932 to 1968, did not encourage the development of higher education. Universities were closed to most of the Portuguese youth. Lisbon was limiting the number of candidates by allowing only a small number of students from the 7th year of Lyceum, which was the last year of high school, to finish their studies. It was already difficult to conclude the 5th year that was the diploma necessary to work as a civil servant, in a bank or in a government office.

Graduates would be the ruling elite, therefore only a few would pass the difficult Exame de Admissão à Faculdade. These numbers were even shorter in the colonies. Aggravating this difficult access to Universities, there were limited numbers of options for Higher Studies in most of the colonies. As a consequence, the elites of what was then called the overseas provinces or Províncias Ultramarinas were seeking higher studies in their neighbour states, where it was much easier and cheaper to travel. Lisbon or Coimbra were too far for one to dare thinking about it. Moreover, in the Goan case, the proximity of British Universities in India made very easy the development of a talented youth who, after college, would be seeking work in the Indian metropolis, where they had migrated for their higher studies.

The network of Jesuit colleges in India

An important note about the number of Universities in India is worth to address. With the decline of the Portuguese eastern overseas empire, along the 17th century, Portuguese entrepreneurship and investment in Christian Propaganda was substantially reduced. Rome was worried about a subsequently lost of clients, or believers, as the new protestant rulers such as Great Britain and Holland were now occupying the ex Portuguese and Catholic realm of influence. As a result, Pope Gregory XV creates Propaganda Fide with the double aim ofspreading Christianity and defending the patrimony of the faith where heresy was damaging its genuinenessas it is mentioned on the Vatican Museums Website.

As part of this policy, the Society of Jesus established a network of Catholic Universities in Mumbai, Bangalore, Kolkata and Madras. At the end of the 19th century Goan elites were travelling to these towns, sometimes with the whole family, aspiring a better future for their children.

The network of Goan parochial schools

Contrasting with this absence of Universities in Goa, a significant part of the educational offer, in the Portuguese Indian Colonies, was a well-established network of primary schools.

Since the beginning of the 16th century, when the Jesuits arrived in India alongside with the Portuguese Navigators, they implemented, in every little village, parochial schools, where learning music became a centenary tradition. It was an easy way to attract children to school, and a clever tool to embellish the Christian rituals, trying to make them as attractive as the Hindu ceremonies at local temples. They also established several workshops where Indian artists were trained to carve, in wood and stone, the Christian Saints that were necessary to decorate the newly built Churches, as well as factories of musical instruments, mainly violins.

This priority of converting local populations to Christianity was a policy of the first centuries of the expansion, enormously pushed by the Portuguese Inquisition, which St. Francis Xavier brought to Goa in mid 16th century. Near two centuries later, when the British established their Indian Empire, their policies were much more business oriented, and such worries with conversions, let alone musical education or carving saints and making violins, were definitively not a priority of Northern European Countries.

Goans were playing a different music and cooking different recepies

But the talent for music of the Goan migrants was not the only attribute they were carrying in their luggage. They also became quite well known as cooks and butlers. After centuries of forcibly being converted to Catholic religion, and Portuguese cultural practices, local populations of Goa were adapted to western manners and nuances, as well as used to eat meat and drink wine, in a way that the majority of other regions of the Indian Subcontinent were not.

British Armed Forces and the tourist industries, not only in India but also in Eastern Africa, very quickly discover those unique western skills, and soon Goans were working in every ship, and every military barrack or hotel. They were the chefs, the waiters, the butlers, or the musicians, either in the Army, the Navy, or in the newly built hotels.

At the end of the 19th century, and beginning of 20th century, the post Industrial Revolution development of transatlantic steamers brought to India a very new cast of rich European travellers. The western elites, merchants, artists, writers and photographers, were avidly visiting and discovering the now accessible exotic East. Among waiters, cooks and musicians that were serving and entertaining the new tourists was certainly a significant number of Goans.

Radio and records colonizing the East with Western music

Other three novelties, of early 20th century, are also going to be very important ingredients for this Bollywood side story: Radio, Records and Jazz. From the 1910s to the 30s, radio went from being an expensive gadget to a cheap commodity. Roughly at the same time the invention of the gramophone enabled the big hits to be played endlessly. The first radio broadcasters were then spreading the musical fashions around the world with a speed never known before.

Because of that technological revolution, jazz that was at the time the dominant form of pop music in the US spread rapidly and became the very first global form of pop music. In the Roaring Twenties or Les Années Folles side by side with jazz, dancing was equally rising in popularity.

The Goan jazz bands

In all Indian metropolis every fancy hotel would want a jazz band, playing in its ballroom, to entertain its guests. Goan musicians were the immediate and readymade answer. Differently than most of the classical Indian musicians they were experienced players of piano, brass and strings, but most of all, they have been trained since primary school to read and write music scores.

Indian excellence of classical music performance was mainly achieved by repeating and improving the same melodies along years of practice, and playing somebody elses creation was a no-no. Reading a score was therefore not a common practice among most of the Indian musicians. Western musicians, on the contrary, were every night mimicking the great successes of their musical heroes. Musical scores and records were avidly sold and every one could reproduce their favourite tune. Consequently Goans took over. Hotel and restaurant bands in most of the Indian towns such as Bombay, Pune, Bangalore, Kochi, New Delhi and Kolkata were mostly bands of Goan musicians.

The decline of Mumbais movida

But in Mumbai these golden years were not going to last forever. Developing since 1939 into the 40s alcohol prohibition was going to severely slow down this nightlife euphoria. Most of the bands were fired and some of the restaurants and ballrooms were closed. That could have been the end of the promising carriers of the Goan musicians.

Goans moving from empty ballrooms to the new film studios

However, more or less at the same time Mumbais film industry was blooming. From an epoch, in the 20s and 30s, of film productions where history and mythology were dominating the scripts, through a post independence era, where social-reformists films were seducing new attendees among the working classes, the cinema of the 50s conquered a massive audience mainly with what was called the Massala Films.

The new genre, or in better words, the new melting pot of genres, included action, romance and comedy, and were punctuated by a series of songs and dancing breaks, following an ancient practice of the classical Indian theatre. Therefore, for the production of these Massala Films, which were the ancestors of what is today frequently addressed as Bollywood, the major film studios had to hire big orchestras, singers and dancers.

Goan diaspora of musicians and artists was going to move quickly from the tourism industry to the new Bollywood adventure. Why Goans? What about musicians from all the other states of India? Goans along the years established a large community of migrants in, and around, the city of Mumbai. In addition, Goan musicians had recently become jobless, after several Mumbai ballrooms were shut down. Also, and more importantly, they had the ability to write and read notations.

Moreover, in late 30s and early 40s, when sound recording pushed sound into the silent movies the use of Hindustani classical music was slowly being substituted by scores played by larger orchestras. Indian instruments were melodic and all the instruments would play around the same line. This was not very effective on the screen.

Movies needed grand orchestras to add more drama to the story

Film directors needed harmonic instruments, and polyphony, which would enhance the drama of their story. Those were exactly the kind of instruments that the Goans were playing in the opera, or the symphonic orchestras, or on the Jazz bands. And so they began to recruit these people to play in the Hindi films.

Goans were also making the recording process much more efficient. As Hindustani music is traditionally orally described, the film composer would have to repeat the tune to the musicians and they all had to go home and practice it for a while until they could nail it.

However, if they were jazz players, or educated in western classical music, the director would just need to give them the score and it would take them only one or two rehearsals until they could all together record the sound track of the film. That was a much more efficient process. So the Bollywood orchestras came to be dominated by Goans who could play harmonic instruments.

But the Goans were also playing a second role; they were not just reproducing notations. They came to be arrangers, or in Bollywood terms, assistant music directors. This was because the composers of the music were also trained in the Hindustani tradition and they themselves didnt know how to notate music.

So normally the director would call the musicians over to his house, and everybody would flop down on cushions. Then he would tell the story and point out where songs were needed. Quoting Naresh Fernandes who writes extensively about Mumbais jazz milieu in books such as Taj Mahal Foxtrot:

The musical director would say things such as: then, when the hero is chasing the heroine through the meadow the scene would burst into a song. After, he would sing a draft of a tune saying: this is how the song should sound like.

The Goan arranger would be next to him noting down what the director was singing. Back to his home, or studio, the Goan arranger would piece these fragments into an entire score. To the bare bones of the verse and chorus, created by the director, he would add several layers of polyphonic music, as well as introduction and interludes.

So the introduction would sound some times like a little fragment of Bach, or it would be something from Duke Wellington, and then the interlude could be a Konkani folk tune. All of these various things would be assembled and together were making Bollywood music this vital crazy form that it is now. (Fernandes, 2012)

In present day, if one looks at the final credits of a Hindi Film, namely the section that refers to the performers of the music, some Christian names, of Portuguese origin, can still be seen there. Most probably these are names of Goan musicians.

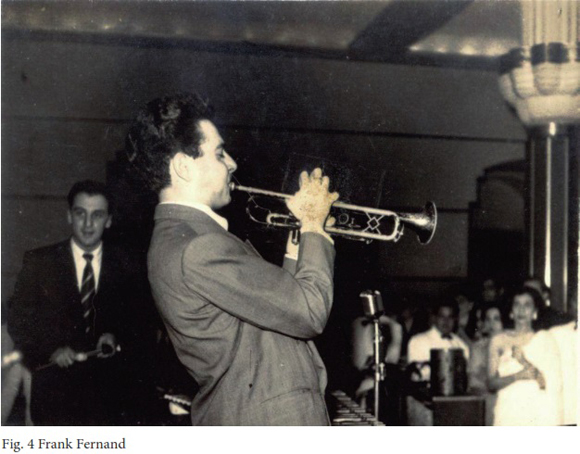

Among these names the ones that are more often remembered, are most likely of jazz players such as Frank Fernand who became later a film producer, or Anthony Gonçalves who gave his name to a Bollywood film, or even of Lucilla Pacheco, a sax player who was later a Bollywood actress.

The story of Frank Fernand

The journey of Frank Fernands life would probably be a good summary of the odyssey of Goans settling in Bollywoods Land. His real name was Franklin Fernandes. According to the e-paper Live Mint (Fernandes, 2011) he studied in the Parish School of Curchorem, the Goan Village where he was born. His teacher, Mestre Diego Rodrigues taught himmusical theory and introduced him in the art of playing hymns and western classical music. At the age of 16 in 1936 he headed to Bombay, where, like so many other Goans, he tried to find work in one of the citys famous dance bands. He settled with his uncle and carried on his studies at Don Bosco High School in Mumbai. Franklin found his first job at the Bata shoe company in Mazagaon.After work, he would perform at the amateur nights at Greens hotel, hopping to attract the attention of someone who mattered (ibidem).From there he went on playing at the Taj Mahal Hotel with George Theodore, and in Mussories Savoy Hotel with Rudy Cotton band. When in 1946 he came back to Mumbai he played with Mickey Correia Band and in 1948 he joined for good the film industry as music assistant, arranger or conductor. From then onwards he worked in more than fifty films.

He always tried to make the difference. Since his youth, still in Goa, where he was practicing violin and trumpet, his dream was to play like a negro (ibidem). However, in 1946, while listening to Mahatma Ghandi, his patriotic Indian feelings were so deeply touched that he decided to be the fist one to play Jazz in an Indian style. He changed his name to Frank Fernand, which he thought would be more suitable for a stage character. To seal his carrier with a golden key he became the father of Goan cinema producing Amchem Noxib [Our luck] in 1963 and Nirmonn [Destiny] in 1966.

Ironically Mumbais film movida is now moving and settling into Goa

In 2007 Franklin Fernandes died in Mumbai at the age of 87. With him, the generation of Goan musicians that was so much involved with Bollywood filmmaking is slowly fading away.

However, Mumbai is ironically paying a tribute to Goa and in recent years turned Goa into a premium film location. Actors and film directors are now buying luxury properties in Goa, mainly old Indo-Portuguese manor houses, which became very fashionable. Equally, enhancing this Goa-Mumbai long-term relationship, Goa became since 2004 the permanent residence of IFFI, the International Film Festival of India.

The end

Sources

This paper was mainly based on filmed interviews, which the author of this paper captured in Goa and Mumbai with Rafael Fernandes, Remo Fernandes, Tomazinho Cardoso, Leslie Menezes, Sushma Prakash, Nickhil Desai, Newton Dias, Sandeep Kotecha, Debu Deodhar, Rajendra Talak, Elvis Gomes, Vinay Bhalia, Partho Gosh and Shyam Benegal.

These interviews were edited in two documentaries of the series Contacto Goa, directed and presented by Francisco Veres Machado. Both documentaries were broadcasted by RTP international, the Portuguese public TV channel, and can be viewed at:

Another series of interviews, also filmed by the author, are still being edited in a new documentary called What happened in 1955, which will probably be released by the end of 2013. These interviews, equally significant for the content of the paper, were filmed in Goa, Mumbai, Lisbon and Cabo Verde with Radha Rao Gracias, Naresh Fernandes, Teotónio de Souza, Suzana Sardo and José Esteves Rei.

References

Dantas, Isidore (2007), Father Of Konkani Films Amchem Noxib, Nirmonn. Frank Fernand No More, Goa World, 2nd April 2007. http://groups.yahoo.com/group/gulf-goans/message/13150. [ Links ]

Fernandes, Naresh (2011), Long gone blues, Live Mint & The Wall Street Journal, 3rd December 2011. http://www.livemint.com/Leisure/d71vX14TxwTNdjAKK8c4PJ/Excerpt--Long-gone-blues.html. [ Links ]

––––, (2012), Taj Mahal Foxtrot: The Story of Bombays Jazz Age, New Delhi: Roli Books [ Links ]

––––, (2013), Swinging in Bombay, 1948, Taj Mahal Foxtrot: The Story of Bombays Jazz Age, 8th June 2013. http://www.tajmahalfoxtrot.com/?tag=frank-fernand [ Links ]

IMDb, Frank Fernand, http://www.imdb.com/name/nm1535865/ [viewed 21st July 2013]. [ Links ]

Vatican Museums, Propaganda Fide, Ethnological Missionary Museum, Collections Online. http://mv.vatican.va/3_EN/pages/x-Schede/METs/METs_Main_06.html [viewed 21st July 2013]. [ Links ]

Wikipedia, Frank Fernand, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_Fernand [viewed 21st July 2013]. [ Links ]

––––, Anthony Gonsalves, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthony_Gonsalves [viewed 21st July 2013]. [ Links ]

Pictures Credits

(1) Portuguese Stamp depicting Mumbai. Pedro Barreto de Resendes Map from 1635

http://oldphotosbombay.blogspot.pt/2011/02/bombay-mapstaxisphotoslife-in-fort-and.html

http://www.girafamania.com.br/asiatico/india-portuguesa.htm

(2) Mickey Correa band at the Taj Mahal Hotel, with trumpet player Frank Fernand in the second row

Courtesy of Naresh Fernandes

http://www.tajmahalfoxtrot.com/?p=441

(3) Lucilla Pacheco, playing the saxophone at Greens Hotel

Courtesy of Naresh Fernandes

http://www.tajmahalfoxtrot.com/?tag=lucilla-pacheco

(4) Frank Fernand, renowned musician and filmmaker from Goa

Courtesy of Naresh Fernandes

[Recebido em 29 de julho de 2013 e aceite para publicação em 18 de agosto de 2013]