INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic has unprecedented repercussions worldwide, not only in health but in global politics, the economy, and individuals' social lives. Nevertheless, its effects are likely to affect men and women differently (OECD, 2020). Previous gender asymmetries regarding unpaid care and housework, in addition to other pre-existing inequalities such as gender-based violence and economic disparity, could be amplified by the unexpected pandemic downturn (Alon et al., 2020; Rosenfeld et al., 2020).

Progressive developments had been made towards gender equality over the 20th century. By challenging traditional gender role-models, including women in the professional sphere, increasing educational opportunities, and implementing egalitarian legislation, women's independence and economic self-sufficiency have increased in industrialized societies (Lyonette et al., 2007). However, the adoption of a dual-earner model (more predominant in Portugal since the Carnation Revolution in 1974) has led to a disproportionate increase in women's total workload, since time spent on unpaid work was not equally reduced (Perista, 2002, 2016; Wall & Amâncio, 2007; Wall et al., 2017). Women still hold most of the domestic responsibilities and frequently take on the burden of reconciling family and work life. In 2017, in Portugal, 37% of women spent at least one hour every day in caregiving tasks, compared to 28% of men, which increases to 87% and 79% for women and men with children. For housework tasks, 78% of women allocate at least one hour to these activities, while only 19% of men do the same (EIGE, 2019a).

To understand persistent gendered asymmetries, it is crucial to examine underlying factors of such dynamics. Whereas reported data on time dedicated to unpaid work allows for a more objective outlook on inequalities, analyzing perceptions of justice regarding unpaid work division provides valuable insights on subjective gender-role norms. Those gender stereotypes are rooted in gendered cultures (Aboim et al., 2010), contributing to the construction of gender roles and attitudes and practices regarding the division of paid and unpaid work (Rodrigues et al., 2015).

Despite a more symmetrical distribution of tasks, perceptions of fairness are not always equivalently expressed. Data from the International Social Survey (2012), collected in Portugal in 2014, showed that younger couples, in childbearing years and with higher educational levels (Wall et al., 2017), were those who perceived more fairness in sharing arrangements. Nevertheless, the increase in men's participation in caregiving and housework tasks is still perceived as insufficient to attain a fair balance. Moreover, highly-educated women are less likely to consider the division of housework as unfair, partially because they can outsource housework and childcare, thus postponing the need to negotiate the division of these tasks within the couple (Amâncio, 2005; Perista, 2016). However, this might not be an option during pandemic lockdown(s).

Conformity to traditional gender roles and stereotypes is likely to be endorsed by both genders during the novel COVID-19 pandemic (Rosenfeld & Tomiyama, 2020). Since women are traditionally the primary caregivers, pressure to provide additional support to children at home may fall onto them. In the need to maintain social distancing, many workplaces resorted to telework, a reality that can potentially disrupt work-family dynamics. Usually, telework can offer flexibility and increase stress levels by alternating from professional to domestic work, particularly for women, blurring the boundaries between professional and family spheres (Casaca, 2002). This may explain why during the initial period of confinement, 54% of women presented positive responses to telework, compared to 62% of men (Silva et al., 2020).

On the other hand, changes brought by the pandemic may promote gender equality. In the overall reorganization of professional and household work, couples' perceptions and behaviors may need to adapt when confronted with these new challenges. When both couple members are teleworking, especially couples with children, the need to better negotiate the division of housework and childcare may become a main concern since the ability to outsource these tasks is limited (Rosenfeld et al., 2020). Additionally, women's overrepresentation in essential work areas (accounting for over 70% of healthcare workers; OECD, 2020) could encourage the legitimization of women's work, both paid and unpaid.

In this paper, we intend to analyze how the current COVID-19 pandemic, particularly how the "state of emergency" lockdown period in Portugal, from March 18th to May 2nd, 2020, affected unpaid work negotiation between heterosexual couples. We expected that the overload of caregiving tasks resulting from schools' shutdown and the increase of housework would affect both men and women, but it is unclear if gender inequality would increase. With this goal in mind, and based on previous work by Amâncio and Correia (2019), we intended to access the relationship between the number of hours spent on housework and caregiving tasks and participant's sex, the perceived justice about the sharing arrangements, and how the lockdown increased men and women's weekly workload of unpaid work. These variables were expected to be impacted by age and educational level but, mostly, by parental status. It is expected that both men and women parenting underage children perceive an increase in both housework and caregiving tasks and that this increased workload would be higher for women than for men.

METHOD

Participants

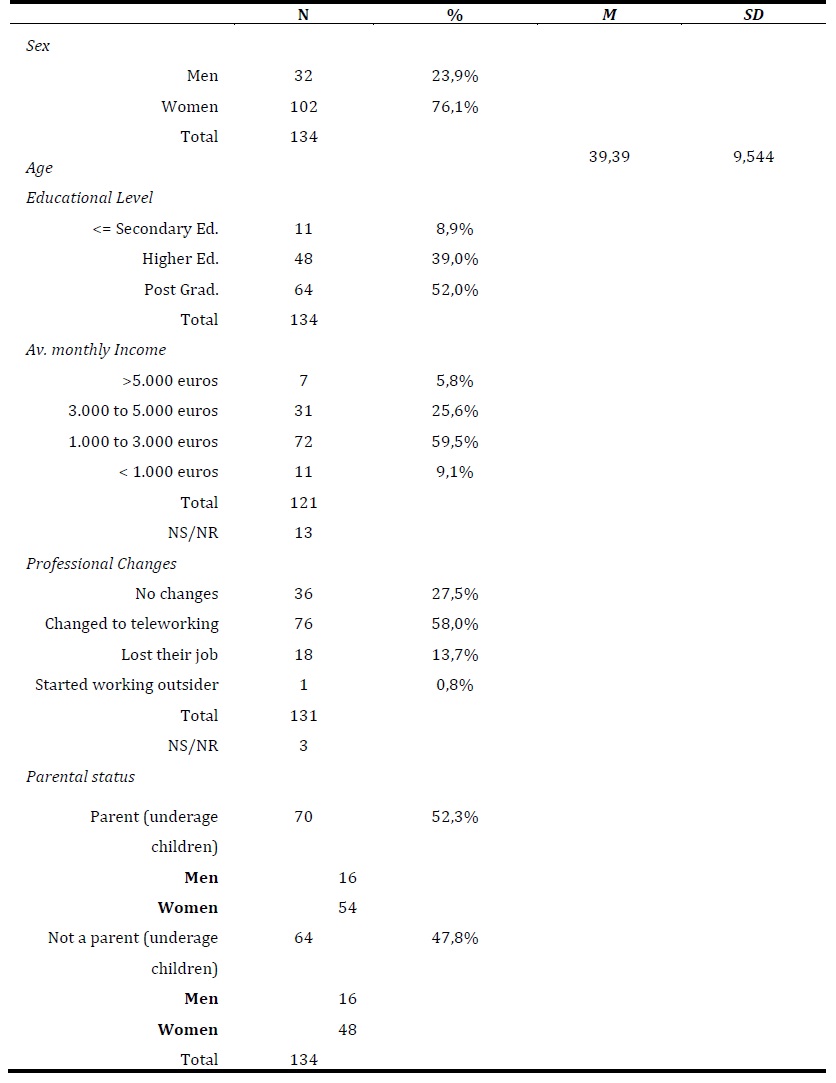

A sample of 218 heterosexual Portuguese men and women answered the questionnaire. It was advertised as targeting Portuguese people over 18 years old, living in a couple in a heterosexual relationship. Only 128 fulfilled our sample requirements for the dependent measures considered in this paper. Participants were aged between 20 and 65 years old (M = 39.39, SD = 9.54). The proportion of women was higher than of men (76%), and an over-representation of high qualified subjects was also identified (91,1%). Most participants changed to telework during COVID-19 (58%), 59% due to COVID-19. It was a convenience sample obtained through sharing a link (by email and social networks), following a snowball method. The dataset did not allow for a dyadic analysis by couple since our focus was not on the couple's interpersonal relationship. This limitation, while relevant, was not detrimental to the results. Demographics are depicted in detail in Appendix 1.

Procedure

Data were collected during the second half of May 2020 (although three accesses were still considered in June) via an on-line questionnaire using Qualtrics (Provo, UT). All recommended ethical procedures were followed, ensuring no risks associated with the participation. For instance, an informed consent was provided, depicting information on the voluntary participation and anonymous data treatment and inclusion criteria and contact information. Participants who consented proceeded to the study. After answering the questionnaire, participants were thanked and debriefed.

Demographics, including age, sex, work status (e.g., teleworking pre and during pandemic/working outside), and marital status, were asked first and used as inclusion/filtering criteria. Sexual orientation was not accessed in this study.

Instrument and variables

Considering our goals, and to have recent pre-pandemic data as a baseline for comparisons, the questionnaire comprised the following measures intended to replicate the previous research in the Portuguese context (Amâncio & Correia, 2019; Amâncio, 2007; Wall et al., 2007):

Hours spent on housework and caregiving: The number of hours spent per week in housework and caregiving were assessed. Estimations for participants and their partners were required.

Perception of justice: This perception was measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1= "I do much more than it would be fair"; to 5 = "I do much less than would be fair" (see Appendix 2).

The questionnaire also comprised a question intended to understand the impact of COVID-19 on the changes perceived in time spent in unpaid work during the pandemic. This variable was measured as follows:

COVID-19 impact on time spent on housework and caregiving was measured using two 5-point Likert-type scale from 1= "Much less hours"; to 5 = "Much more hours" (see Appendix 3).

Additional variables were measured outside the scope of this research and, thus, not analyzed here (satisfaction about sharing arrangements, number of hours spent in paid work, and qualitative questions about reasons for gender differences, advantages and disadvantages of teleworking).

RESULTS

Housework and Caregiving weekly hours

Data were analyzed considering sociodemographic variables (age, income, changes in professional arrangement during COVID-19, and educational level) as covariates. None of those showed a significant effect on the variables analyzed. Therefore, results are presented without covariates.

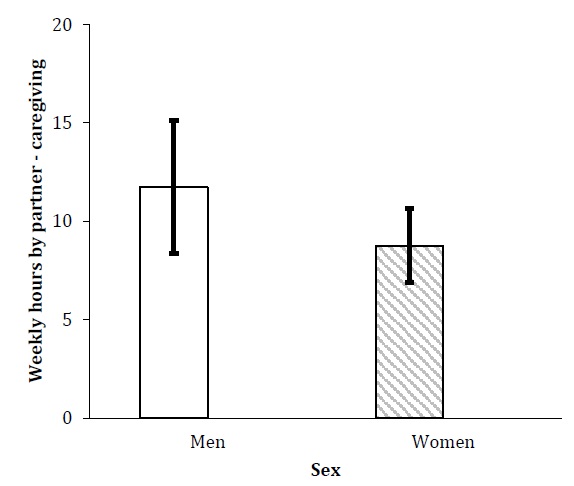

A multivariate 2x2 GLM was conducted with sex (men vs. women) and parental status (parent/not a parent of underage children) as factors, and weekly hours spent on housework and caregiving, for self and partner as dependent variables (see Appendix 4 for correlations). Multivariate tests showed a significant sex, F(4, 127) = 12.50, p < .001, η 2 p = .28, and parental status difference, F(4, 127) = 3.83, p = .006, η 2 p = .11, but not an interaction between both, p = .078. Between-subjects effects showed a significant sex difference in partner’s caregiving hours F(1, 130) = 15.24, p < .001, η 2 p = .11: men estimate their partner spent more hours (M = 11.73, SD = 16.80) than women’s estimations about hours spent by their partners (M = 9.12, SD = 20.88) (Figure 1).

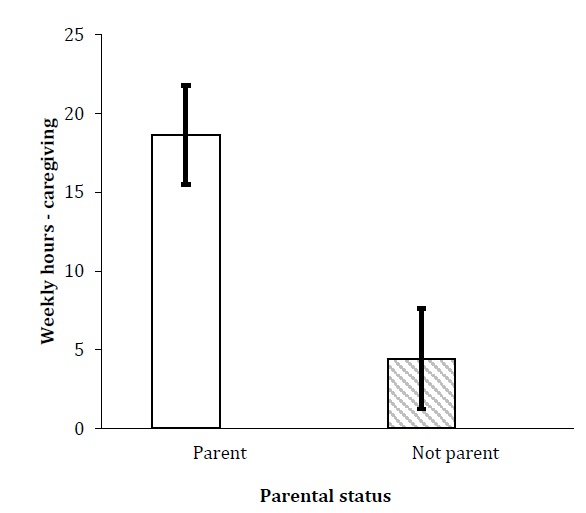

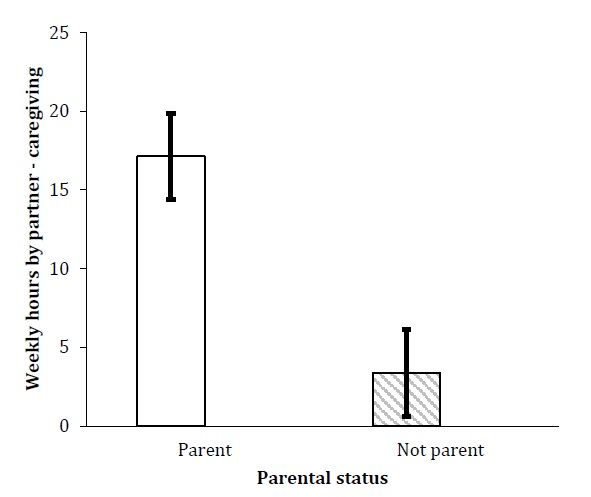

Moreover, there was a significant difference in their own caregiving hours F(1, 130) = 10.16, p = .002, η 2 p = .07) by parental status. Participants with underage children spent considerably more hours in caregiving (M = 21.51, SD = 28.89) than other participants (M = 4.46, SD = 10.40) (Figure 2). There was also a difference in partners’ hours: parents of underage children estimate their partners spent much more hours (M = 15.82, SD = 24.68) than non-parents (M = 3.09, SD = 9.35) (Figure 3).

Figure 1 Weekly hours spent by partner in caregiving tasks, by sex (estimated marginal means and standard errors)

Figure 2 Weekly hours spent in caregiving tasks, by parental status of underage children (estimated marginal means and standard errors)

Figure 3 Weekly hours spent by partner in caregiving tasks, by parental status of underage children (estimated marginal means and standard errors)

Perception of justice on sharing arrangements

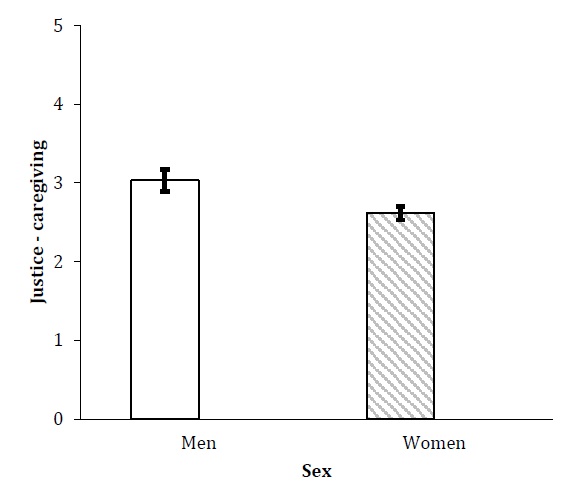

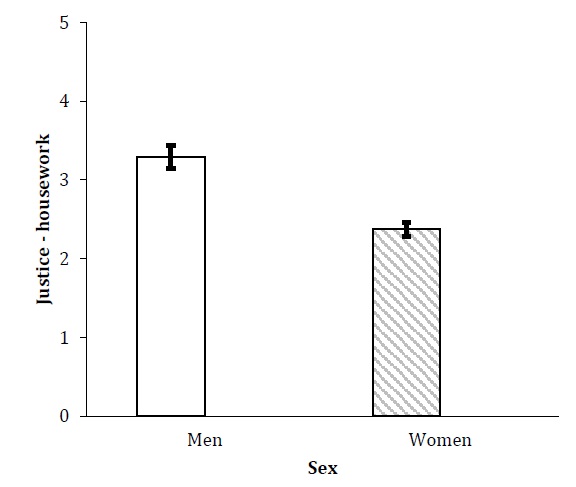

A similar 2X2 multivariate GLM was performed, with perceptions of justice concerning housework and caregiving division as dependent variables, and sex and parental status as independent variables. There was only a multivariate effect of sex, F(1, 105) = 14.28, p < .001, η 2 p = .21. Between-subjects effects showed sex differences for both, housework F(1, 106) = 28.79, p < .001, η 2 p = .21 (women perceived that they did more than would be fair [M = 2.37, SD = 0.81] compared to men [M = 3.29, SD = 0.60]), and on caregiving F(1, 106) = 6.67, p = .011, η 2 p = .06 (M = 2.56, SD = 0.80 for women; M = 3.04, SD = 0.51 for men). Differences are depicted in Figures 4 and 5.

Figure 4 Perceptions of justice in the division of housework by sex (estimated marginal means and standard errors)

Changes compared to pre-COVID-19

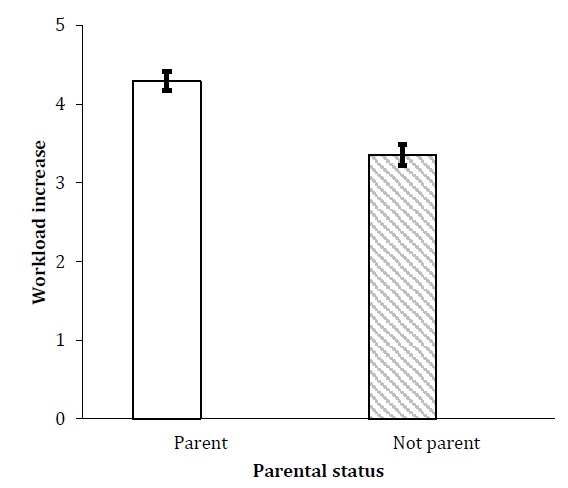

A similar 2X2 multivariate GLM was performed, having perceived changes in housework and caregiving as dependent variables. A multivariate effect of parental status was found F(1, 115) = 13.77, p < .001, η 2 p = .19. Between-subjects effects showed similar perception of changes in caregiving for both men and women, but different perceptions depending on parental status, F(1, 116) = 26,91, p < .001, η 2 p = .19. Parents reported spending much more weekly hours on caregiving (M=4.28, SD=0.86) than other participants (M = 3.49, SD = 0.83) independently of sex, ps > .10 (see Figure 6).

DISCUSSION

Our main concern was to address how the current COVID-19 pandemic could affect the decreasing trend of gender inequalities in unpaid work (EIGE, 2019b), which was slowly being achieved, at least for highly educated and younger couples (Amâncio & Correia, 2019). For couples in childbearing years, the effects on paid work and the overload of caregiving resulting from school closures could affect men and women very differently and jeopardize the progress made at this level, but also provide opportunities to renegotiate gender roles at home (Alon et al., 2020; OECD, 2020).

The results suggest that gender and parental status might be important variables in analyzing weekly hours devoted to caregiving, increasing with underage children. Other sociodemographic variables (i.e., age, income, changes in professional status, education level) did not significantly covariate the results. Even the change to teleworking- a factor with enormous disruptive potential for families- did not covariate the results.

In fact, despite being a very small, homogeneous sample, with low representation of men, thus not allowing for much extrapolation, we verified the same trends as in past research (Amâncio & Correia, 2019; Perista, 2016; Wall et al., 2017): women spent more hours on caregiving than men, and men perceived their partners weekly hours on caregiving to be higher than women perceive for their partners. We found, therefore, an awareness of asymmetry by both men and women.

Regarding both housework and caregiving tasks, female participants perceived that they did more than would be fair during the pandemic compared to men, seeming to be aware of the gender asymmetries in terms of domestic work, but men were also aware of this asymmetry (Amâncio, 2007; Amâncio & Correia, 2019; Perista et al., 2016).

In general, everyone (regardless of sex or parental status) appeared to perceive spending more time on unpaid work during lockdown than before. However, parental status was, here, a differentiating factor, with parents of underage children (regardless of sex) reporting spending many more hours per week than before COVID-19. These results underline the importance of differentiating policies to mitigate the effects of COVID-19 in families with small children, paying particular attention to this particularly vulnerable group.

The fact that the increase of time spent on domestic work and caregiving during COVID-19 did not appear to be influenced by sex indicates that men also increased their overall domestic participation, which is positive. However, since women also felt this incremental change, a decrease in the disparity on gender division of unpaid work is not probable.

In this study, several limitations must be addressed: the sample is very small, especially for men, resulting in a lack of power to demonstrate gender effects. Also, the snowball method and on-line recollection produced a biased sample of highly educated participants that is not generalizable for the Portuguese population.

Nevertheless, in our study, we could not find the same optimistic trends in reducing inequalities in comparable subgroups (younger, more educated couples, with small children) as in recent, pre-COVID studies. In these extraordinary times, family dynamics negotiation was "put on hold" as a secondary aspect. Overall, in our sample, the pandemic seems to have reinforced gender inequalities in unpaid work. Both in the short-term and the long run, this can be detrimental for reducing gender asymmetries in paid and unpaid work.