Introduction: The failure of the ecological transition from above

Since the climate strikes of 2019, and even more so after the acknowledgment of the environmental roots of the COVID-19 pandemic, the ecological transition seems to be everywhere. While the European Union turned it into the cornerstone of its recovery strategy, some European Union governments have even established brand new ministries just for it. Nonetheless, a succinct historical recognition is sufficient to moderate such enthusiasm. In fact, it is at least since 1992 - year of the renowned Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro - that, under the aegis of the United Nations, the involved countries legislate according to a strategy that we can define as ‘ecological transitionfrom above’. The core idea behind it is simple but ground-breaking: it is not true, as it was formerly believed, that environmental preservation and economic growth are mutually exclusive. To the contrary, the green economy - if properly understood - allows for internalising the ecological limit, which is transformed from a ‘blockage’ to capitalist development into the ‘foundation’ for a new cycle of accumulation.

Focusing our attention on transnational climate governance, the adaptation of such core idea is that even if global heating is a market failure, resulting from the fact that so-called ‘negative externalities’ are not accounted for, the only way to deal with it is the establishment of further markets to price - and exchange - different types of ‘nature as commodity’, for example forests’ capacity to absorb CO2. These are not wild trips to a Platonic realm of abstract theory: such flexible mechanisms for the com- modification of the climate, established by the Kyoto Protocol in 1997 and relaunched by the 2015 Paris Agreement, are still the main economic policy tool deployed by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. The message is clear: ‘give a price to nature - the problem will be solved’.3

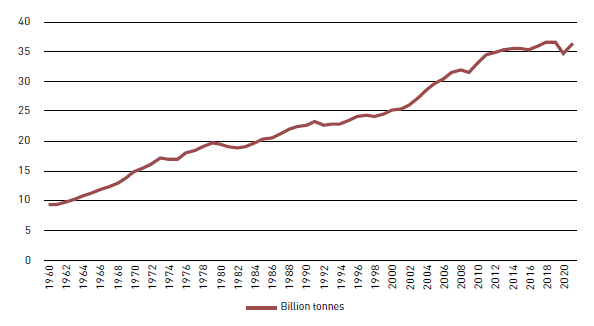

Since the beginning, the promise ofthisecological transition - applied to global heating - was ambitious and explicit: the ‘invisible hand’ of the market would be capable of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and, concurrently, of guaranteeing high profit rates. No doubt, a quarter-century is a timespan long enough to evaluate the effectiveness of a public policy, even more so in the case of the ecological crisis, as the urgency to take decisive action is in this regard obvious. The question, thus, is: have emissions declined?

This graph is quite eloquent: no, emissions have not declined.

Rivers of ink have been spilled to debate the reasons for such debacle. Here are some hypotheses: excessive ‘generosity’ in the allocation of the quotas, imperfect information, ubiquitous corruption, design flaws, regulatory shortcomings. Nonetheless, the result - which is what counts - is crystal clear: placing the market as the pivot of economic and climate policy does not lead to a decline in emissions, but to further increases. Being aware of this, we can proceed to pose the question of strategic converging between workplace struggles and climate justice today.5

The working-class roots of political ecology

Before reaching the heart of the matter, two warnings are in order. The first concerns the fact that the ecological transitionfrom abovesuggests a compatibility - more, an elective affinity - between environmental protection and economic growth6 only under the condition of relegating the labour movement, with its social function of contrasting inequality, to the margins - or, worse, to the role of an actor resisting change in the name of protecting ecologically unsustainable jobs. The subject of the green economy is the ‘self-entrepreneur’: daring, enlightened, smart.Her/hisinnovating charge, in fact, springs from an indifference towards the shackles posed by intermediate bodies (unions in the first place) and the time-wasting red tape of institutional mediation, particularly democratic practices. This generates a tendency - second warning - to assume that the cause of labour and that of environmentalism are hopelessly at odds. The underlying idea is that the job blackmail - ‘your health or your wage’ - is essential to the fate of industry.7

Such narrative has been given a certain historiographic legitimation but, even if the latter is not completely false, it is certainly partial and far from innocent. Dating the first widespread politicisation of the question concerning the environment to the period between the late 1970s and the early 1980s - that is, after the great cycle of struggles of the Fordist phase - is in fact an implicit internalisation of the defeat of the so-called Long 1968, an extraordinary season of mobilisations which had pointed to economic democracy as the necessary condition to contrast workplace environmental degradation - including air, soil, and water pollution - in some cases eliminating it completely.

To avoid any misunderstandings, let us clarify that there is no way around the fact that such defeat happened. It is however legitimate to question its putative inevitability. Furthermore, the constant deterioration of the material bases of the biosphere’s reproduction makes it extremely urgent to look at that historical turn from a new perspective. The marginalisation of the labour movement, in fact, has not come with the eradication of industrial noxiousness. Despite decades of climate negotiations, over the last thirty years, the amount of greenhouse gas emissions has exceeded the total produced between the 18th century and 1990. It is necessary to break free from the fetish of a complicity between capital and the environment to open the space to (re)link ecological and labour movements. This is - in a nutshell - what we need, and it is perfectly exemplified by the ex-GKN Plan for a Public Hub for Sustainable Mobility, as we shall see. Against this background, reinterrogating the conflicts around noxiousness that took place between the 1960s and the 1970s allows for demonstrating that ecological issues became widely politicisedthanks to, notin spite of, the labour movement.8 It was in the wake of harsh and innovative disputes such as those at FIAT’s painting units9 or Montedison’s chemical plants10 that the demand for a healthy environment - first in the factory and later in the territories surrounding it - was turned from a tech-nicality into the political stake of trade union and social movement struggles.

We can use the evocative formula ‘working-class environmentalism’11 to designate the constitution of a partisan knowledge focused on the workplace. The latter thus became a peculiar type of ecosystem as the working class turned it into its ‘natural’ habitat, ending up knowing it better than anybody else. It is not by chance that the conflicts against industrial noxiousness were the first to fiercely criticise the so-called ‘monetisation of health’, that is, the notion that wage increases and bonuses could compensate for the exposure to toxic substances - sometimes deadly - and other forms of occupational hazards. It was around the impossibility of indemnifying health damage that key figures of those battles - such as Ivar Oddone12 in Turin and Augusto Finzi in Porto Marghera - centred enduring militant campaigns, whose trail is easily recognisable in the 1978 health reform, which established Italy’s national health service.13

Two important elements must be added to the picture. The first is that the struggles against industrial noxiousness would not have had such a disruptive impact without their connection to broader mobilisations asserting the centrality of social reproduction, thanks to the developments of feminist thought. The second aspect is that the labour movement did not manage to reach a unified strategy: there rather emerged a tension between the perspective of a ‘redemption of’ wage labour - supported, for example, by Bruno Trentin, who at the time was the secretary general of Federazione Impiegati Operai Metallurgici (FIOM), the largest metalworkers’ union - and that of a ‘liberation from’ wage work, embraced by the workerist organisations such as Potere Operaio first and Autonomia Operaia later.

We think it reasonable to suppose that the incapacity to reconcile these two options around the common demand for a reduction of the working day (with no wage cuts) was a significant element in the defeat of that cycle of struggles. Instead of a working-class power over the qualitative composition of production, what occurred was capital’s violent reaction:14 fragmentation of labour, retrenchment of the welfare state, accelerated financialisation, as well as - environment-wise - the ecological transitionfrom abovewe have just outlined. However, as the failure of such strategy becomes manifest, the game reopens. The memory of the struggles of half a century ago takes on a renewed relevance today and the question of strategic converging between workplace disputes and climate and environmental mobilisations reveals itself as an extremely timely one.

‘Converging to rise’, within and against the ecological crisis

The defeat of the Long 1968 propelled us into a world ofnoxious deindustrialisation, a phrase that designates employment deindustrialisation in areas where significantly noxious industries are still operating.15 According to the recently updated estimates by the International Labour Organisation (ILO), the global share of manufacturing employment has slowly but steadily declined from 15.6% in 1991 to 13.6% in 2021. Over the same period, fossil fuel-generated carbon emissions - which include those from devi- ces produced by industry but used in all other sectors and by final consumers - increased from 23 to 36 yearly billion tonnes (as shown by the graphic in the Introduction). Furthermore, between 1991 and 2018, the emissions generated by industry directly shifted from 4.4 to 7.6 billion tonnes according to Climate Analysis Indicators Tool. In sum, the logic of profit resulted in both (relative) job losses in the factories, with the precarisation of employment that usually follows them, and in the deepening of environmental devastation.

The unprecedented temperatures, droughts, poor harvests, melting glaciers, and deaths caused by extreme weather that we witnessed in 2022 are the umpteenth confirmation that the situation is dramatic. We areinthe ecological crisis, not merely as the victims of the highly unequally distributed impacts of environmental devastation along class, ‘race’, and gender lines on a global scale. We are in the crisis because, in our society, the subsistence of the working class depends on capitalist work and therefore most people depend on the infinite growth of commodity production. In this sense, the job blackmail does not concern highly noxious productive facilities only, it is rather an intrinsic and transversal property of capitalism, which appears with variable levels of intensity in different contexts.

To pose the question of how to strengthen an environmentalism from below, we think it useful to update the method of class composition16 analysis along three lines: 1) an expanded conception of the working class, defined by the compulsion to sell its labour power; 2) a conception of work including both production and reproduction; 3) a conception of working-class interests17 encompassing both the workplace and the community (or territory).18

Firstly, we consider as part of the working class all those who - dispossessed from ownership and control of significant magnitudes of means of production - live under the compulsion to sell their labour power, both for the production of commodities and for the reproduction of additional labour power, independent of whether they find stable buyers or not. Even if this conceptualisation excludes the middle class - to which capital delegates some responsibilities in the management of society - it is nonetheless broader than the narrow dominant views; broad enough to include the unemployed, reproductive workers, informal workers, subordinated intellectual workers, and dependent self-employed workers.

Secondly, following social reproduction feminism,19 we define as capitalist work all those activities - waged and unwaged, directly productive and reproductive - explicitly or invisibly subordinated to capital accumulation, regardless of the economic sector. The dispossessed, in fact, work either in the making of commodities (directly produc- tive work) or in the non-directly-commodified making and maintaining of an employable workforce for capital (reproductive work). The distinction between directly productive and reproductive work is determined not by different types of concrete activities, but by the ‘frontier of decommodification’.20

Thirdly, we see working-class interests as related to both the workplace and the com- munity or territory. The distinction between workplace and community - similarly to the one between production and reproduction - is not based on different physical spaces but on social relations: the workplace is the domain of ‘workers-as-producers-or-reproducers’ while the community is the sphere of ‘workers-as-reproduced’.21 Working-class interests are often conceived as workplace-centred (job security, high wages, health and safety, etc.). No doubt, wealth redistribution via higher wages for shorter hours would help to overcome the jobs versus environment dilemma by reducing the need for jobs in the first place. Yet, in any case, workers do not disappear after leaving their workplaces. To the contrary, they return to their neighbourhoods, breathe the air outside the factories and offices, enjoy their free time by relating to the ecologies surrounding them. Working-class interests, then, do not involve only workplace rights, but also the conditions of their communities (consumer prices, welfare services, healthy ecologies, etc.).

The triple expansion of working-class, work, and working-class interests proposed here is meant to overcome those perspectives that reinforce the job blackmail. In fact, if ‘real’ work is waged and industrial only and thus the ‘real’ working-class is disproportionately male (and white, until recently), and if ‘real’ working-class interests mainly consist in keeping one’s job as it is, a way out is beyond reach. Such impasse further deepens if community mobilisations are seen as devoid of any class content, as if the inhabitants of the mostly working-class communities affected by severe environmental injustices did not have to work for a living. Conversely, an inclusive understanding of such concepts lends itself more easily to the building of coalitions among workers differentially located within the gender-race class system.

In workerist theory, the ways in which workers are deployed, segmented and stratified in the workplace through different economic sectors, labour processes, wage hierarchies, commodity chains, etc. constitute the technical composition of the working class, its ‘objective’ side. The political composition of the working class, instead, indicates the extent to which workers as a class overcome, or not, their divisions to assert their common interests vis-à-vis capital. This is the ‘subjective’ side, made up of workers’ forms of consciousness, struggle, and organisation. Seth Wheeler and Jessica Thorne usefully proposed to update this frame by adding the social composition of the working class, that is, the ways in which workers are reproduced in the community, for example through family, housing, welfare, and health regimes.22 The objective side of class composition is then bifurcated between technical composition (related to the workplace) and social composition (related to the community).

From this perspective, it is possible to analyse how the working class is segmented also in relation to environmental degradation. For example, the fence-line communities living by highly polluting industries are often disproportionately composed of the most disadvantaged ranks of the working class, in many cases racialised too, and do not necessarily have widespread access to jobs in the factories. For these working-class segments, local ecological transitions would mean a welcome drop in higher-than-average cancer rates and other diseases. For workers employed in polluting industries, though, the situation is different, even if not necessarily irreconcilable. For them, ecological transitions more likely represent a risk of ending up in more precarious and lower-paying jobs.

The challenge of beingagainstthe ecological crisis is thus that of breaking the blackmail by creating convergences between workplace and community struggles.23 This step is far from automatic, as the working class is fragmented along a myriad of occupational and residential configurations, an objective reality that too often fuels divisions between trade unionism as the expression of workplace interests and ‘environmentalism from below’ as the expression of working-class community interests. It is about striving to re-compose such segmentations politically, building platforms of demands to articulate together workplace and community struggles.

The ex-GKN dispute and the ecological transitionfrom below

The struggle of the ex-GKN Factory Collective is a key step in the construction of an alternative to an ecological transitionfrom abovethat - as it avoids questioning the system that produced the crisis - does not have much to offer in the way of real sustainability. In fact, recovering the red thread of working-class environmentalism, the Collective gave a practical, militant demonstration that the convergence of workplaces and territories around the watchwords of climate justice is a viable strategy.24 Their innovative approach was in fact able to generate broad mass mobilisations, repeatedly bringing to the streets tens of thousands and thus managing to alter restructuring plans that have not encountered impactful resistance in comparable situations elsewhere.

Let us briefly recall what happened in Campi Bisenzio: up until 9 July 2021, GKN blue collars used to produce axle-shafts, mostly for luxury cars. However, on that day Melrose Industries - the financial owner of the plant - sent out an email announcing the dismissal of more than 400 workers. The dismissal was portrayed as the natural outcome of the ‘ecological transition’ in the automotive sector: ‘Haven’t you embraced Greta?!?’, the mainstream narrative reproached the radical unionists of the Factory Collective. ‘Now accept the inevitable layoffs!’25 But they refused to accept them and launched a permanent assembly within the factory - which is still operating today.26

At first, these workers demanded one usual thing: to get back their jobs. As weeks passed, however, they realized the only way to keep production running was to advocate for a public and (territorially) integrated factory, which essentially meant to profoundly change production. In what direction? Well, here is probably their most significant intuition, as the answer was:towards climate justice. In a joint declaration with the Italian branch of Fridays for Future (25 July 2022), blue collars and young protesters put forward a clear argument:

‘The reality is that climate justice (CJ) cannot be achieved without touching the deepest and most dominant economic interests in society. CJ cannot be achieved without clashing against the dense web of economic interests at the top of society. To achieve CJ, it is crucial to radically rethink the production and consumption model, which is currently based on a strong power asymmetry. This implies, among other things: collective ownership of key economic sectors in order to conduct industrial policy in line with ecological principles; necessity and sufficiency; lowering the consumption of the wealthiest, thereby protecting the weakest segments of the population, while simultaneously decreasing the climate burden of consumption of the super-rich and establishing, through redistribution, truly universal welfare measures that recognize the importance of care activities’.27

Such process goes well beyond the fate of the factory itself, as indicated by a previous joint statement, again by the ex-GKN Factory Collective and Fridays for Future to launch the successful demonstrations of 25-26 March 2022:

‘A real climate, ecological, and social transition cannot disregard the capacity of a society to establish comprehensive and sustainable forms of planning. And such planning can- not be generated through workplace blackmails and hierarchies or in the oppression and repression of the communities - as it has been the case for years, for example, in the Susa Valley - but it must come from an awakening of radical, participative democracy’.28

Finally, such ‘radical, participative democracy’ insists on an inherent connection between working-class environmentalism, social mobilization at large and climate justice:

‘The drought, the melting of secular glaciers, and the ever more intense heatwaves are the dramatic confirmation of the changes engendered by global heating. We are cons- tantly struggling to reach the end of the month, against precarity, against outsourcing, against inflation, and for a dignified wage. However, the struggle for the end of the month has no sense if we do not win that against “the end of the world”. And it is impossible to get increasing shares of the population involved in the struggle against the end of the world if we do not join it with the struggle to reach the end of the month’.29

Such words grasp the systemic dimension of our predicament. Commodification, in fact, is a wedge separating capitalist production from life reproduction and subordinating the latter to the former. Profit does not rely on infinite growth only, but also on the capacity to produce things that people will buy. However, market consumption choices are intrinsically individualist and short term, while democratic planning is collective and potentially far-sighted. The conversion plan drafted by the ex-GKN Factory Collective and their Solidarity Research Group is an example of how such apparently faraway horizons can encounter, even in today’s unfavourable political conjuncture, a concrete outlet: nationalisation under workers’ control for the creation of a Public Hub for Sustainable Mobility. The idea was to keep producing axle-shafts, but for electric buses, because the automotive sector, within the framework of an ecological transition from below, cannot but rely on a strong critique of the private car. The plan gathered a lot of attention, gained recognition by the Ministry of Economic Development and was eventually published by Fondazione Feltrinelli. Yet, no Government so far has had the courage to promote a regional supply chain for collective public mobility.

Confronted with a deaf political system, the Factory Collective kept working with climate justice movements to free up space for imagining a politically attractive ecological transitionfrom below. Together with the qualitative dimension of decommodification, the quantitative, distributive aspect related to income levels and working hours must also be tackled: ‘We demand a reduction in working hours with no wage cuts, so that work quotas be equally redistributed across the population. It is possible to work less if everyone works, and it is a right that every worker, of today and tomorrow, should fight for’.30

Indeed, the rising prices of food and energy over 2022 - which have generated a wave of mass mobilisations and revolts in manifold countries (Peru, Ecuador, Panama, Sri Lanka, Sierra Leone, etc.) - confirmed that no ecological transition will be possible without wealth redistribution on a global scale.

Conclusion: Workers’ cooperatives as instances of an ecological transitionfrom below?

What we see rising, we argue, is the unprecedented profile of an ecological transition from below. Here are some key elements of it: decommodification of production, reduction of working hours, redistribution of wealth. The convergence between workplace and community struggles, of which the ex-GKN dispute is an example, will be a crucial node for the broad mobilisations necessary to reach the end of the month while moving beyond the end of the world.

In this sense, even when confronted with a blatant lack of political will to even consider the feasibility of the Public Hub for Sustainable Mobility - which is to say, in the last few months - the Factory Collective refused once again to capitulate. Through a new round of exchanges with the Solidarity Research Group, the workers came up with the Reindustrialization Project 2.0. One of the goals is to contribute to the decarbonization of small-scale logistics both in large workplaces and in Italian cities which are still far from uniformly adopting sustainable mobility plans. The first cargo-bike prototype was realized in a few months and presented in February 2023, with technical designs coming from knowledge shared by eco-social enterprises and raw materials coming from recycled components.

The project of such work-recovered enterprise31 is still in its inceptive phase and has received funding from a successful crowdfunding campaign called ‘ex-GKN FOR FUTURE’, supported by Fridays for Future Italy, BancaEtica (an ethical banking institution, close to the cooperative and social movements) and ARCI, the oldest network of entertainment and cultural clubs in Italy. As activist-scholars Francesca Gabbriellini and Paola Imperatore put it:

‘the idea is to build a popular shareholder base to support the new project: the land the factory is built upon will be the first shareholder of this small eco-revolution. The first step of the campaign is aimed at accumulating the necessary funds to concretely launch the workers’ cooperative. In less than a month, with the participation of hundreds of citizens and associations, the crowdfunding campaign has already exceeded 175.000 euros’.32

It might look like the working class has finally realised that its leadership is necessary for the ecological transition from below to actually stand a chance to become the most ambitious climate justice-inspired policy ever imagined.