Introduction

Capsule endoscopy, first described in 2000, was one of the most important advances in the investigation of small bowel diseases. A swallowed pill camera acquires images, subsequently converted to video format on a computer, as peristalsis propagates it through the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, allowing a noninvasive endoscopic evaluation of the GI tract [1, 2]. Since its first use 20 years ago, several models were developed, with the purpose of evaluating other GI segments, beyond the small bowel [3].

In 2006, the first double-headed capsule for colonic observation was developed - the PillCam COLON® (Given Imaging, Medtronic) which has been primarily used for colorectal cancer screening in average risk populations or when colonoscopy is contraindicated or incomplete [4, 5]. With two cameras recording simultaneously, one in each side of the capsule, the first-generation capsules had a sleep mode to save battery while traveling through the GI tract. The capsule shut down 5 min after ingestion and restarted to transmit images again 2 h after ingestion, in order to preserve the battery life during the progression of the capsule along the small bowel [3]. In 2009, a second generation of this capsule was developed (PillCam COLON2®), allowing a wider angle of vision and an enhanced adaptative frame rate - a technology that permits changing the rate of image capture from 4 to 35 frames per second, according to the velocity of progression of the capsule [3, 5]. Some recent studies have focused on the potential role of double-headed capsules in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) and colonic Crohn’s disease (CD) [6].

The idea of observing the entire small bowel and colon mucosa, in a single noninvasive procedure, was tested in several clinical scenarios, from GI hemorrhage to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), due to the development of those double-headed capsules with long-lasting batteries [3, 7]. A few studies have reported the use of the PillCam COLON® for a complete evaluation of the GI tract by turning off the sleep mode, this marking the beginning of pan-enteric evaluation [3]. Boal Carvalho et al. [4] demonstrated that PillCam COLON2® allows for a new concept of noninvasive, safe, and well-tolerated examination of the entire GI tract.

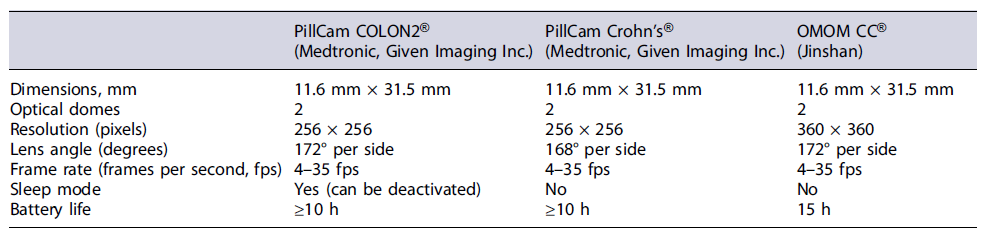

In 2017, a new double-headed capsule named PillCam Crohn’s® (Given Imaging, Medtronic) was released, combining two wide-angle cameras that permit a 344°-wide view between the two extremities of the device, with a long-lasting battery (over 12 h) [3, 6]. The pill is similar to the second generation of the PillCam COLON® in its hardware components but is designed to allow complete coverage of the gut from the mouth to the anus without any interruption in recording, allowing a panoramic vision of the GI tract in a single procedure. This new capsule comes with a dedicated software, in which the small bowel is divided into three segments according to their approximate length and the colon is divided into two parts (right and left) [8]. Not having a sleep mode avoids the need for early activation or manual turnoff, which eliminates the risk of accidental loss of small bowel frames [3]. Recently, another double-headed capsule was released for use in clinical practice (OMOM CC®, Jinshan), fulfilling the technical characteristics required to perform a pan-enteric capsule endoscopy (PCE) - Table 1.

PCE reduces the need for invasive procedures with the associated increased risk of complications and extra costs, allowing observation of all the bowel in a single procedure, in a more attractive and comfortable way for the patient [3, 7, 9]. Capsule endoscopy avoids insufflation or sedation, although it still requires bowel preparation, and the risks associated with the procedure are reduced (capsule retention and potential bowel obstruction), although still more frequent in patients with established Crohn disease [4].

Procedure

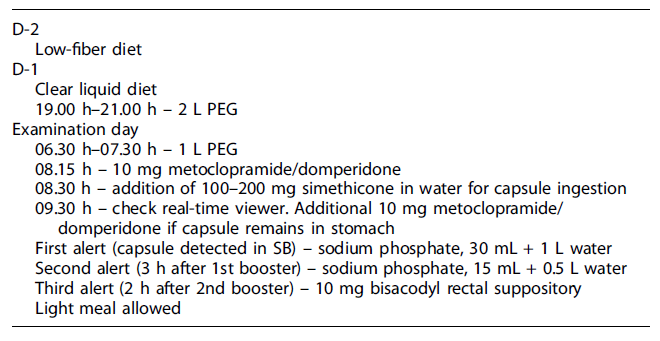

The PillCam® Crohn’s system is composed of four subsystems: the PillCam® Crohn’s capsule; the PillCam® recorder; the PillCam® software, and the Given® Workstation [10]. Bowel preparation includes a clear liquid diet on the day prior to capsule swallowing and administration of a polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution divided into two doses: in the evening before and in the morning of the examination day [11]. Following capsule ingestion and depending on its progression through the digestive tract, the recorder receives and interprets real-time input from the capsule and provides audiovisual guidance to patients throughout the procedure; an additional laxative boost, such as the sodium phosphate, is required in order to enhance capsule propulsion and maintain adequate cleansing of the colon [10, 11]. Table 2 summarizes the current standard bowel preparation protocol for PCE. The PillCam® data recorder emits sequential alerts along the examination, which trigger patient procedures and assist medical decisions: alert 0 informs the patient should take a prokinetic drug, such as metoclopramide 10 mg or domperidone 10 mg tablet by mouth; alert 1 suggests the intake of a laxative boost; alert 2 suggests the intake of a second laxative boost, after 3 h; alert 3 is given when there is a need to take a 10 mg bisacodyl suppository, after 2 h; alert 4 allows to eat a standard light meal, 2 h later; alert 5 marks the ending of the procedure and can occur any time after receiving alert 1.

All laxative boosts should be followed by the intake of additional water during the following hour. Clear liquid ingestion is permitted throughout the examination and preparation [11].

Clinical Applications

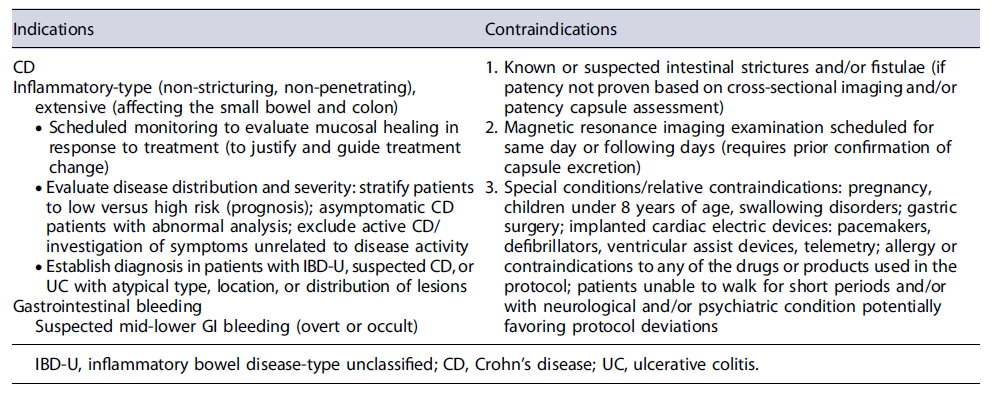

Current main indications and contraindications for PCE are summarized in Table 3.

Inflammatory Bowel Diseases

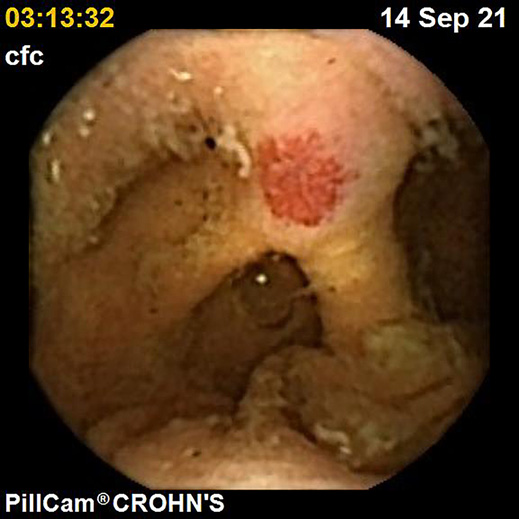

IBDs are a group of GI disorders characterized by chronic inflammation of the GI tract. The two main types of IBD are CD and UC. Colonoscopy and small bowel capsule endoscopy have a definite role in the management of patients with IBD [12]. The advent of PCE, allowing concomitant enteric and colonic evaluation, has created the expectation that this modality may allow a comfortable and accurate evaluation of the GI involvement in IBD in a single examination [3, 13]. Moreover, for IBD evaluation, patients are often submitted to separate colonic and small bowel evaluations, the latter frequently by radiologic exams. Hence, panenteric systems may also allow the avoidance of repeated exposure to radiation and overcome the limited sensitivity of radiology in recognizing inflammatory activity in proximal segments of the small bowel and colon segments [14]. Figures 1-3 document some examples of small bowel and/or colonic ulcerated lesions detected by PCE.

Crohn’s Disease

Given CD’s discontinuous nature and disease location, a pan-enteric approach is a valuable option for simultaneous evaluation of SB and colonic lesions, making PCE a convenient method to evaluate disease severity, extent, and distribution [15]. In fact, PCE can provide high diagnostic yields for lesion detection in the entire GI tract in these patients [16-18]. In a recent study by Yamada et al. [19], the diagnostic yield of PillCam COLON2® for detection of lesions in both small and large bowels was analyzed using double balloon enteroscopy as the gold standard. Overall, PCE sensitivities for ulcer scars, erosion, and ulcers were 83.3%, 93.8%, and 88.5%, respectively, and the specificities were 76.0%, 78.3%, and 81.6%, respectively. Other studies have evaluated the diagnostic performances of PCE using the PillCam COLON2® or PillCam Crohn’s® capsule in patients with CD. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Tamilarasan et al. [2], which included seven studies evaluating the performance of PCE for the detection of CD lesions, found a comparable diagnostic yield of PCE compared to magnetic resonance enterography and colonoscopy (pooled OR of 1.25 [95% CI: 0.85-1.86%]). In fact, there was a trend to superiority of PCE over MRE and colonoscopy, with an increased diagnostic yield of 5% and 7% for PCE compared with MRE and colonoscopy, respectively.

The role of PCE in postoperative settings has also been addressed. A study by Hausmann detected 50% (6/12) of active disease 4-8 months after surgery, whereas ileocolonoscopy detected significant inflammation in 33% (5/15)[20]. Mucosal healing is increasingly recognized as an important treatment goal in patients with IBD. The concept of treat-to-target underlying IBD management frequently requires endoscopic evaluations to assess mucosal healing. For that reason, a single-time pan-enteric evaluation is appealing. In a multicentric study by Tai et al. [21] PCE was performed in 71 patients with established CD and led to a change in disease management in 33 (46.5%) of patients.

Despite the good performance of PCE in comparison with other endoscopic and imaging modalities, PCE detects only mucosal changes, so it might be insufficient to fully assess disease status (transmural and extramural involvement) [22]. Scoring systems allow for the standardization of reporting, increasing reproducibility and interobserver agreement [23]. Whereas most scores have been established for colonoscopy and small bowel CE, their application in PCE to monitor IBD mucosal disease activity has also been proposed [13]. Niv et al. [24] extended the validated Capsule Endoscopy Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CECDAI) score to include the colon, introducing the novel CECDAIic score, allowing for an objective pan-enteric assessment of CD inflammatory activity [25]. In 2019, Arieira et al. [26] applied the CECDAIic score in a cohort of CD patients who underwent PCE and found an excellent interobserver agreement (Kendall’scoefficient 0.94) and strong correlation with inflammatory parame-ters, especially calprotectin (rs = 0.82; p = 0.012).

A novel PillCam Crohn’s® capsule score (Eliakim score) for quantification of mucosal inflammation in CD was also developed. In this score, the whole bowel is divided by length into five segments: the small intestine is divided into three tertiles, and the colon is divided into two (the right colon and the left colon). The score integrates the most common lesion, the most severe lesion, the extent of disease, and the presence of strictures [11]. In this initial study, the correlation between the two readers was excellent for Lewis score and PillCam Crohn’s® capsule score (0.9, p < 0.0001 for both). The correlation between PillCam Crohn’s® score and fecal calprotectin was stronger than for Lewis score (r = 0.32 and 0.54, respectively, p = 0.001 for both) [27].

Regarding safety, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis reported a 2% rate of capsule retention for all indications, with a twofold increase in the setting of CD (relative risk = 4%) [28], while another meta-analysis described a retention rate of 4.63% (32 studies, 95% CI:[3.42; 6.25]) in patients with established CD versus 2.35%(16 studies, 95% CI: [1.31; 4.19]) in patients with suspected CD [29]. Although the risk of capsule retention is increased overall in patients with CD [29], it may be significantly decreased with the rationale use of dedicated small bowel imaging such as CT or MR enterography and/or patency capsule, particularly in the case of obstructive symptoms, known stricture or prior SB surgical anastomosis [30-32], where a patency capsule is still required even in cases of unremarkable cross-sectional imaging [31].

PCE seems to be a safe and feasible tool to examine the whole GI tract in patients with CD with a high diagnostic yield for CD lesions detection [33]. However, despite these encouraging results, the precise role and indication for PCE in CD remain unclear due to lack of large scale and randomized controlled trials.

Ulcerative Colitis

In recent years, several studies have shown a very good overall agreement between PCE and colonoscopy for assessing disease activity [34-36]. In 2013, a study by Hosoe et al. [37] found that endoscopic scores deter-mined by the PillCam COLON2® showed a strong correlation with scores obtained by conventional colonoscopy (average ρ = 0.797) in UC patients. In 2018, Hosoe et al. [33] developed an endoscopic severity score for the PillCam COLON2®. The final scoring system was fixed as “vascular pattern sum (proximal + distal) + bleeding sum + erosions and ulcers sum (minimum-maximum, 0-14)” and was named Capsule Scoring of Ulcerative Colitis (CSUC) [33]. Overall, the CSUC was an easy-to-use score consisting of three simple parameters (vascular pattern + bleeding + erosions). The correlation coefficient of CSUC with biomarkers and clinical score was similar to that of the Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS) [38].

More recently, a systematic review and meta-analysis, including data from seven studies, showed that PCE had a diagnostic sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of 70% for the detection of UC [2]. Interestingly, a 2014 study using the PillCam COLON® or PillCam COLON2® in UC patients found that a small percentage of patients (7.1%) changed the diagnosis of UC to CD due to inflammation observed in the small bowel [39]. In fact, IBD remains unclassified in up to 10-15% of cases after conventional colonoscopy and histology [12], and PCE may have an important role for clarifying the diagnosis in patients with unclassified IBD. Histopathology is crucial not only for the diagnosis but also for disease monitoring. Histological remission is considered a desirable target along with symptomatic and endoscopic remission [22]. Moreover, initial diagnosis and surveillance for dysplastic changes or colitis-associated cancers are also needed [40]. The use of PCE for diagnosis and surveillance lacks the ability to provide histological information.

Cost-Effectiveness Considerations

There is already a great volume of publications on the topic of cost-effectiveness in the use of PCE for colorectal cancer screening. However, there is still little evidence of its use in IBD. A British National Health Service study proposed to evaluate the cost impact of PCE in IBD patients (vs. colonoscopy ± MRE). The authors found that, although initial costs were higher using PCE due to the earlier initiation of biologics, in the longer term, there was a financial benefit due to reduction in surgical interventions [41]. A study from USA assessed the cost and patient impact of using PCE for scheduled monitoring of CD. The results showed that the patient groups of PCE showed increased quality of life and increased life expectancy, making it a cost-effective option [42]. There are no data available on the cost-effectiveness in patients with UC.

PCE in Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Despite being far more well established in the setting of IBD investigation, PCE is currently gaining further interest as a potentially useful procedure in many other clinical scenarios [43]. One of the most prominent and recently studied indications is GI bleeding, either overt (presenting as melena and/or hematochezia) or in the occult form as chronic iron deficiency anemia, due to its large prevalence in everyday clinical practice.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy represents the first-line examination in patients presenting with melena [44]. Nevertheless, the examination can be inconclusive in up to 20-25% of the cases [45]. Therefore, colonoscopy is subsequently used to investigate patients presenting with melena after a nondiagnostic esophagogastroduodenoscopy. However, its diagnostic yield is not as high as expected, with the rate of therapeutic colonoscopies in this setting being even lower [45].

Small bowel capsule endoscopy has systematically been recommended as the first-line investigation procedure in patients with obscure GI bleeding - bleeding from the GI tract with negative findings in both esophagogastroduodenoscopy and ileocolonoscopy - which accounts for approximately 5% of all GI bleeding events [46]. Ever since, capsule endoscopy application in the event of obscure GI bleeding or iron deficiency anemia has almost exclusively been reserved to isolated small bowel examination.

However, after PCE establishment, there has been a shift in this classical scenario, due to hypothetical advantages associated with this innovative diagnostic procedure. On one hand, capsule endoscopy now allows the examination of all GI segments on a single procedure [47]. Furthermore, an adequately timed pan-enteric evaluation may eventually avoid unnecessary inconclusive examinations, with subsequent organizational and economic benefits, as described by Rondonotti et al. [48]. Finally, capsule endoscopy is a technique easily accepted by patients when compared to other conventional endoscopy procedures, especially in terms of safety and comfort [49]. Figures 4, 5 represent cases of small bowel and colonic angioectasias, respectively, detected by PCE. For these reasons, there is now an ever-growing evidence on the use of a pan-enteric endoscopic approach in patients with GI bleeding, especially those in whom an upper digestive tract lesion has already been excluded, as this strategy could lead to a quicker identification of the bleeding site, drive further management, and potentially avoid other unnecessary examinations [50]. Moreover, it is already known that capsule endoscopy is able to detect proximal lesions missed by upper digestive endoscopy in a significant percentage of the individuals [51].

In 2018, Yung et al. [52] reported that patients with negative upper GI endoscopy and subsequent small bowel capsule endoscopy had shorter mean times from admission to capsule and hospital stays compared to those patients who underwent capsule endoscopy after negative upper and lower GI endoscopy. Therefore, the authors finally concluded that earlier access to capsule endoscopy in patients with melena or iron deficiency anemia, no signs of lower GI pathology, and negative upper GI endoscopy resulted in shortened hospital stays, good diagnostic yield from both the small bowel and upper GI tract, and two-thirds less unnecessary colon investigations.

In 2021, Mussetto et al. [50] conducted a study aiming to assess the feasibility and performance of PCE in patients presenting with melena and negative digestive upper endoscopy. This investigation included a total of 128 consecutive patients presenting with melena, clinically significant bleeding and negative esophagogastroduodenoscopy, who then underwent PCE by swallowing the PillCam COLON2® capsule. In this proof-of-concept study, PCE was feasible and safe, identifying the bleeding site in 83% of patients. This led to small bowel therapeutic interventions in 50% of patients, thus avoiding unnecessary standard colonoscopy in a significant percentage of the included individuals.

A similar retrospective investigation was made by Carretero et al. [7] by analyzing 100 consecutive PCE performed in a GI bleeding setting. Positive findings were observed in 61% of the patients, with 46% having a previous negative upper endoscopy. The capsule detected small bowel lesions in 68% and colonic findings in 81% of the individuals. According to the authors, no further endoscopic studies would be needed in nearly 65% of the patients with negative gastroscopy. Thus, PCE with a capsule device could be useful and safe in bleeding high-risk patients by selecting those who would eventually need further therapeutic endoscopy.

Due to these recent developments, there is a new and interesting window for the use of PCE in suspected GI bleeding and investigation. Further prospective and multicenter studies are needed in order to clarify the practical role of capsule endoscopy in this setting, especially in patients presenting a high risk for invasive endoscopic procedures, and the specific indications and timing to use it.

Other Clinical Applications: Limitations and Future Perspectives of PCE

Although the clinical applicability of PCE in the context of IBD, particularly CD [16, 17, 21, 53], and digestive hemorrhage [50, 52], has been demonstrated in recent studies, its window of use in other clinical scenarios remains narrow. Capsule endoscopy has previously been shown to be useful in the diagnosis of various esophageal diseases, such as varices [54] and Barrett’s esophagus [55]; however, it has not been proven cost-effective when compared with traditional endoscopy. Its role in the diagnosis of gastric lesions, on the other hand, is limited by the extent of the mucosal surface and inability to control capsule movements.

The possibility of using a noninvasive pan-endoscopic method may seem appealing in the context of polyposis syndromes with simultaneous involvement of the small intestine and colon, such as familial adenomatous polyposis, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, or juvenile polyposis syndrome. The role of conventional small bowel capsule endoscopy in the surveillance of polypoid syndromes is well established. Schulman et al. [56] prospectively evaluated 29 patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. From patients with duodenal adenomas, 24% had additional polyps in the jejunum or ileum. The authors concluded that this endoscopic capsule should be considered in the evaluation of these patients. In another study of patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, Caspari et al. [57] demonstrated a superior diagnostic accuracy of CE compared to magnetic resonance imaging in detecting polyps <5 mm. Regarding colon evaluation, double-headed capsules have demonstrated validity in recent years in diagnosing polyps and screening for colon-rectal cancer - Figure 6. A prospective study of 884 asymptomatic patients evaluated initially by the PillCam COLON2® and subsequently conventional colonoscopy demonstrated a sensitivity of 81% and specificity of 93%for detection of polyps ≥ than 6 mm and a sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 97% for polyps ≥ 10 mm [58]. In 2017, the American Multi-Society Task Force positioned capsule colonoscopy as a 3rd-line test in colorectal cancer screening. ESGE also recommends its use as a screening method for colon-rectal cancer only in moderate risk groups, when conventional colonoscopy is incomplete or contraindicated [59]. The limitations of this method are mainly related to the suboptimal adequate preparation rates, the rate of incomplete examinations, the complexity of bowel preparation regimens, and lack of therapeutic capabilities.

These limitations are also transposable to the limitations of PCE. The diagnostic accuracy of the capsule as a pan-endoscopy tool is highly dependent on several parameters such as preparation quality, transit time, complete exam rate. Its applicability also depends on other factors such as patient acceptance and availability of human resources for reading and interpretation [49].

In a recent paper by Vuik et al. [49] evaluating PCE, the rate of patients with adequate colonic preparation (76.6%) was clearly below the standard recommended in conventional colonoscopy (>90%) [60]. The issue of adequate preparation is furthermore corroborated by a recent systematic review [3], where only 54% of studies had >90% of exams with adequate preparation. Vuik et al. [49] also reported complete (“mouth-to-anus”) examination rates of only 51%, similar to other publications [7, 11, 19] and clearly lower than recommended [60]. Another limitation relates to patients’ acceptability. Although capsule endoscopy is a painless and noninvasive method compared to conventional colonoscopy, the complexities of bowel preparation regimens negatively influence its acceptability [49, 61].

In the same work by Vuik et al. [49], the limitations of gastric/esophageal evaluation became apparent. The Z-line was visualized in less than 50% of the patients, indicating an overly rapid esophageal transit; and although visualization of the gastric mucosa was considered good/excellent in most patients, capsule endoscopy does not allow for adequate observation of the gastric fundus.

The introduction of artificial intelligence systems for assisted reading of these exams is expected to address other current limitations of pan-enteric techniques, decreasing reading times and improving lesions’ detection [62]. In a proof-of-concept study conducted by Ferreira et al. [63] in the setting of CD, a deep learning model for automatic detection of small bowel and colonic ulcers and erosions using PillCam Crohn’s® capsule images was developed, with an overall sensitivity and specificity for lesions’ detection of 90.0% and 96.0%, respectively.

Conclusion

New perspectives in the field of capsule endoscopy are being devised. PCE seems feasible, effective, and safe, and it has been increasingly explored in IBD and, more recently, GI bleeding, with promising results. Used individually, traditional endoscopic means for evaluation of the esophagus, stomach, and colon remain superior to PCE. However, PCE offers the unique opportunity to evaluate several digestive segments at the same time in a single noninvasive examination. Current well-established clinical indications include the evaluation of inflammatory-type (non-stricturing, non-penetrating) and extensive (affecting the small bowel and colon) CD, mainly for scheduled monitoring to evaluate mucosal healing in response to treatment. The use of PCE may also be useful to establish the diagnosis in atypical cases of UC, suspected CD, or inflammatory bowel disease-type unclassified. More recently, in the context of GI bleeding, PCE has been proven useful in patients with suspected overt or occult mid-lower GI bleeding.

With the introduction of further technological advances such as steerable capsules, intelligent image analysis systems [64], and refinement of protocols, PCE is expected to become an increasingly prevalent tool in future clinical practice, by allowing a noninvasive, safe, and comfortable diagnostic approach for a variety of diseases affecting the small bowel and the colon. PCE appears therefore in the verge of a new paradigm toward expanding the field for noninvasive endoscopy, enabling the direct endoscopic coverage of the entire surface of the small and large bowel in a single examination, and limiting the demand for invasive procedures such as conventional colonoscopy and/or device-assisted enteroscopy, which are expected to be tendentially reserved only for those patients who require biopsies and/or therapeutic procedures, based on the findings first detected by PCE.