Introduction

Syphilis is an infectious disease caused by Treponema pallidum that has long been known for its heterogeneous clinical presentation1. If untreated, it can progress through four distinct stages: primary, secondary, latent, and tertiary1. Diagnosing secondary syphilis can be particularly challenging in daily practice due to its diversified skin manifestations. It is historically known as “the great imitator” since it can mimic several other conditions such as psoriasis, lichen planus, folliculitis, or pityriasis lichenoides chronica1. In addition, unusual clinical manifestations of syphilis are more common in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive patients2. To highlight a particularly rare form of presentation, with few cases well-reported in the literature3-5, we present a case of pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA)-like secondary syphilis in a HIV-positive patient.

Clinical case

A 33-year-old male presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 3-month history of a skin rash that started with generalized erythematous macules. In the week before presenting to the ED, the lesions had progressed to multiple generalized papulovesicles and papules with central necrosis and serohemorrhagic crusts, some exhibiting a “collarette” scale, with no pain or pruritus. There was concomitant nasal discharge, earache, and fever, with no mucosal lesions. The patient referred that the lesions had appeared after an occasional job at a poultry farm. He denied high-risk behavior for sexually transmitted infections (STI) but mentioned a bisexual behavior.

Regarding his medical history, the patient had been diagnosed with HIV-1 infection 5 years before but then missed all subsequent appointments and abandoned treatment. A month and a half before the observation in the ED, he had returned for a follow-up of HIV infection. His viral load was 33.900 copies/mL and CD4 lymphocyte count was 632/mm3 serologic tests for syphilis (venereal disease research laboratory [VDRL] test and chemiluminescence assay [CLIA]) were all negative. He did not return to initiate antiretroviral therapy.

Physical examination demonstrated multiple generalized infiltrated erythematous papules, papulovesicles, and plaques, predominantly on the face and dorsum, with a varioliform-like appearance (Fig. 1A and B). Several lesions had already ulcerated and were covered with a serohemorrhagic crust, resembling a “tache-noir”. Some of the rounded lesions presented a “collarette” scale, particularly on his back (Fig. 2A) and feet (Fig. 2B). No mucosal lesions were identified in the oral, genital, or anal regions. There was also generalized lymphadenopathy. The clinical hypothesis of PLEVA, rickettsiosis, disseminated fungal infection, and syphilis was considered.

Figure 1 A and B: skin presentation on the face and dorsum. Multiple erythematous papules and papulovesicles, some of which have already a necrotic center and are covered by a serohemorrhagic crust.

Figure 2 A and B: skin presentation on the dorsum and feet. Rounded brown-to-red papules covered by a “collarette” scale.

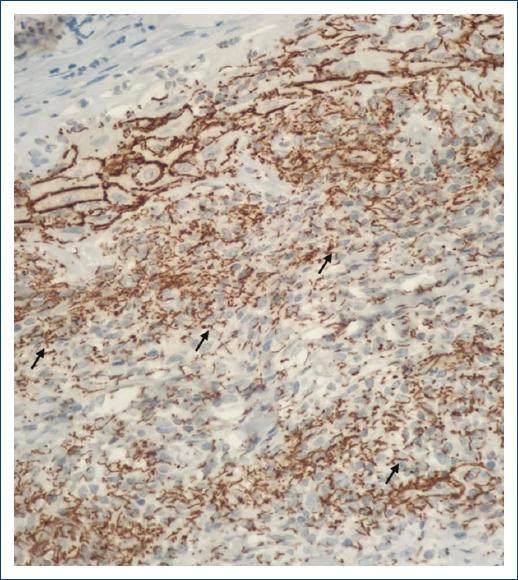

A skin biopsy revealed interface dermatitis with a predominantly superficial lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, compatible with the suggested diagnosis of PLEVA. Serologies (Rickettsia, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C virus), and tissue culture (for mycobacteria and fungi) excluded other relevant infections. Both treponemal and non-treponemal tests were positive (VDRL 1:256; CLIA positive). Since the previous blood sample (1 month and a half before) was still preserved in the laboratory, the VDRL test was repeated, after dilution, to exclude a prozone effect, and was negative. Immunohistochemical staining using polyclonal antibodies anti-T. pallidum (MAD-000624QD from Master in vitro, Sevilla, Spain) in skin tissue revealed the presence of multiple spirochetes on the epidermis and dermis, predominantly surrounding the superficial vessels (Fig. 3).

Figure 3 Detection of Treponema pallidum using immunohistochemical technique. Multiple spirochetes (black arrow) were detected on the epidermis and dermis using polyclonal antibodies directed against T. pallidum in paraffin-embebbed skin biopsy samples. The spirochetes were predominantly deposited around the vessels, particularly the superficial plexus (immunohistochemistry with anti-T. pallidum antibody × 200).

The diagnosis of PLEVA-like early secondary syphilis was assumed, and a single dose of 2.4 million units of intramuscular benzathine penicillin was prescribed. The patient later revealed that he occasionally engaged in transactional sex with men. The remaining workup did not reveal any other STI (Chlamydia Trachomatis, Neisseria Gonorrhoeae, hepatitis B and C viruses). He returned after 3 months, with near-complete resolution of skin lesions and negative VDRL titers. We were lost to follow-up after failing four scheduled appointments.

Discussion

Dermatologists and other clinicians should be aware of the high diversity of syphilis’ clinical presentation and this awareness seems to be more important than ever when we look through the current data on the epidemiology of the disease. In spite of not being as common as other STIs, syphilis is a systemic condition with an increasing frequency over the last decade6,7. Indeed, a recently published report by the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control revealed that although there has been a deceleration in the escalation of syphilis cases compared to the period of 2010-2017 (with annual rates ≤ 7.0/100,000 population), the incidence of confirmed syphilis cases in 2019 surpassed that of preceding years, reaching a rate of 7.4/100,000 population8. The majority of cases in high-income countries occur in men who have sex with men, with a considering proportion of these patients having a HIV coinfection2,9. The diagnosis of syphilis in patients coinfected with HIV poses a clinical challenge due to their heightened susceptibility to develop atypical cutaneous manifestations2.

PLEVA is a rare cutaneous inflammatory condition more frequent in young adults and children10. The pathogenesis of the condition remains poorly understood-several theories have been suggested, including a hypersensitivity reaction that represents an aberrant immune response to bacterial, viral, or protozoal infections10. It typically presents as an acute and recurrent skin eruption with a predilection for the trunk, skin flexures, and proximal extremities-and with no mucosal involvement10. It is characterized by multiple papules and papulovesicles that rapidly evolve to central necrosis and serohemorrhagic crusts10. Occasionally, patients can experience some infectious symptoms, usually before skin lesions. Some patients might develop a Mucha-Habermann disease - de novo or as a progression from a pre-existing PLEVA -, which seems to be an intensified version of PLEVA, with a more severe clinical presentation and associated symptoms11.

Regarding our case, the fact that our patient had a past medical history of an uncontrolled HIV infection and of unprotected sexual intercourse led us to think of the possibility of an atypical presentation of secondary syphilis. The ulcerated pustular eruption as a variant of secondary syphilis-higher intensity reported in HIV-coinfected patients-that can mimetize PLEVA describes this case perfectly. The non-occurrence of Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction led us to avoid the historical nomenclature “malignant syphilis” to describe this case of secondary syphilis. In the authors’ opinion, it is plausible that certain cases reported in the literature as PLEVA or Mucha-Habermann in HIV patients could potentially represent the ulcerated pustular eruption of secondary syphilis, which might lead clinicians to be misled by a false-negative VDRL test.

The fact that he mentioned a 3-month evolution of skin lesions, but had negative serologic tests (both VDRL and CLIA) for syphilis 1 month and a half after the beginning of the cutaneous rash is interesting, and should be discussed, but remains to be completely understood. We could have had a prozone phenomenon on VDRL, but a false-negative in a CLIA test occurs in < 1% of the cases12. With that being said, we assumed an early secondary syphilis, with two main possibilities that might justify the whole picture: (1) skin lesions had < 3 months of evolution-several reports of simultaneous manifestations of primary and secondary syphilis in HIV patients, which shortens the time to for the appearance of secondary syphilis’ cutaneous manifestations; (2) or there was another cause for the initial multiple erythematous macules that was not detected in the emergency room or on the following outpatient appointment.

All these findings and discussion highlight the need for clinicians to be aware of this differential diagnosis, to be excluded when there is a context that makes it plausible. Furthermore, it reinforces the fact that secondary syphilis might have several cutaneous presentations, particularly in HIV patients, and dermatologists have an extremely important role in reducing the impact of the disease in our community with the right treatment.

Conclusion

In conclusion, heightened awareness of the various clinical forms of syphilis is imperative for clinicians, particularly dermatologists. This awareness is amplified by the escalating prevalence of syphilis despite its relative rarity compared to other STIs - recent epidemiological data, including a report from the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control, underscores the persistent increase in syphilis cases, with a considering proportion of those patients being HIV-coinfected individuals. Ultimately, this clinical case emphasizes the pivotal role of dermatologists in effectively addressing diverse presentations of syphilis within our community.