Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Tourism & Management Studies

versión impresa ISSN 2182-8458

TMStudies no.7 Faro dic. 2011

Cooperation of Small and Medium-Sized Tourism Enterprises (Smtes) With Tourism Stakeholders in the Malopolska Region – Top Management Perspective Approach

Cooperação de pequenas e médias empresas (PME) de Turismo com stakeholders de turismo na região de Malopolska – uma abordagem da gestão de topo

Krzysztof Borodako

Senior Researcher, Cracow University of Economics krzysztof.borodako@uek.krakow.pl

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this paper is to understand the difference in number of relations of small and medium-sized tourism enterprises (SMTE) with tourism stakeholders in the region. This research used an email survey sent to tourism CEOs, directors or owners of SMTEs in the Małopolska region, focusing on its capital city -Cracow (Poland). All three groups of respondents in SMTEs were understood in the research as the top management of these companies.

The study conducted made it possible, on the basis of the statistically significant results, to analyze the differences as regards the level of cooperation between companies depending on the company size, micro firms and SMTEs, their belonging to different subsectors and the company age. Observations show that such differences exist and should be used by the SMTEs managers and tourism policy makers.

The largest part of the researched sample usually cooperates with one to five partners from each stakeholder group. A surprising conclusion was the high level of cooperation with competitors from the same subsector – almost one third of the accommodation and catering firms collaborate with more than five competitors.

KEYWORDS: Tourism, Cooperation, SMTE, Network, Top Management.

RESUMO:

O objetivo deste trabalho é compreender a diferença no número de relações de pequenas e médias empresas (PME) de turismo com agentes de turismo (stakeholders) na região. Esta pesquisa utilizou um questionário enviado por e-mail para ceos de turismo, diretores ou proprietários de pequenas e médias empresas de turismo na região Małopolska, com foco na sua capital -Cracóvia (Polónia). Todos os três grupos de inquiridos de PME de turismo foram considerados na pesquisa como a gestão de topo dessas empresas.

O estudo realizado tornou possível, com base nos resultados estatisticamente significativos, analisar as diferenças quanto ao nível de cooperação entre empresas, dependendo do tamanho da empresa, as micro, pequenas e médias empresas, a sua pertença a diferentes segmentos e a idade da empresa. As observações mostram que tais diferenças existem e devem ser utilizadas pelos gestores de pequenas e médias empresas de turismo e responsáveis políticos da área do turismo.

A maior parte da amostra pesquisada geralmente coopera com 1-5 parceiros de cada grupo de interessados. Uma conclusão surpreendente foi o alto nível de cooperação com concorrentes do mesmo segmento -quase um terço das empresas de alojamento e restauração colabora com mais de cinco concorrentes.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Turismo, cooperação, PME de turismo, rede, gestão de topo.

1. INTRODUCTION

The dynamic development of tourism industry is possible mainly due to the creation and usage of the network benefits. The participation in the network is particularly important in case of small and medium-sized tourism enterprises (SMTEs) and is particularly supported in the rural areas, but tourism plays an important role also in the city. At the same time the significant part of the tourism and hospitality industry are SMTEs (Morrison 1998; Page, Forer& Lawton, 1999), which usually do not possess enough resources to run businesses separately. For that reason it is the SMTEs that are most interested in cooperation with stakeholders in the tourism and hospitality industry. According to the statistical data, in 2009 in the Accommodation and Catering sector there were 55 271 micro firms with up to 9 employees in Poland(about 3.32% of all micro firms in the country), with around 150 000 employees in total (CSO, 2010:4). According to the available data about tourism in the Małopolska region, in 2008 there were 10 705 micro companies in the Hotels and Restaurants sector, which was 3.75% of all micro firms in the region. But the share of micro companies in the Hotels and Restaurants sector in >Małopolska shows a significant role of this kind of the companies. In the aforementioned sector, in 2008, the micro and small companies (up to 50 employees) constituted 99.51% of all companies of that sector and SMTEs are a part of 99.94% of all companies in the Hotels and Restaurants sector (CSO, 2009).

One of the key attributes of cooperation between different partners is the number of relations during a particular time period. The number of different contacts, mostly among the SMTEs owners or managers, is the most popular characteristic of cooperation. It is necessary to mention many reasons why owners or managers decide to cooperate with other entities in the tourism industry – mostly within a close range (local or regional environment). The most popular motivation for such cooperation is lack of the required resources: information, knowledge, human resources, but also financial or organizational resources. In many cases SMTE are too small or too weak to buy or lease the missing resources on competitive conditions. To prepare and offer an interesting product on the tourism market, the companies need to possess various skills and resources usually within a short period of time. In such a situation the owners or managers of SMTEs see their chance in close cooperation with other tourism stakeholders.

The aim of this article is to provide an insight into density of cooperation and to critically analyze cooperation of SMTEs with other regional stakeholders in the tourism industry from the point of view of the number of relations. This gives rise to three main objectives focused on the dependence of cooperation on the subsector, size and age of the company. The outcome is better understanding of the field, the rules and the interdependences of the SMTEs’ networking activities on the regional level. Finally, the conclusion critically reflects on the significance of the results for other tourism regions.

2. METHODOLOGY

On the basis of statistical data which confirmed that the key players in the tourism sector are the SMTEs, the research was based on that group of enterprises. The process of collecting telephone and address data of tourism companies in the Małopolska Region was conducted by means of three key methods: a) recording the contact data of the tourism companies that cooperate with the research team, b) the Snowball sampling after a contact with companies that cooperate with the research team and c) searches in company databases at popular internet sources. The collected database of the companies consisted of 1812 unique e-mail addresses of different businesses in tourism industry in the region. The main subsectors selected in the research were: accommodation, catering, transport companies (passenger transport), private tourism attractions, travel agents, tour operators, bicycle rental shops etc.

The inquiry form was prepared in an electronic version on the internet website with access granted to companies that were invited by a special e-mail invitation. At the beginning there was a pilot project -150 e-mails with invitations to database records selected at random. After the assessment of the response, a decision was made to change the invitation text. Afterwards 150 records selected at random were sent emails with the modified invitation. A few days later after the evaluation of the response, the invitation was sent for the first time to the remaining entities from the tourism industry in the amount of 1512. After receiving an automatic failure delivery response, selected emails addresses were carefully checked again by means of telephone contacts with the company or by careful internet pages scanning. Finally, out of 1812 emails sent to unique addresses, 198 addresses were incorrect, so the final number of the delivered invitations was 1614. As a result of filling the inquiry forms we received 195 completed records from SMTEs companies fulfilled by the owner, CEO or director of the companies. In that research we assume that all that people represent the top management in micro, small and medium-sized companies in the tourism industry.

The collected data were analyzed by statistical methods. The number of relations with the tourism stakeholders, divided by groups of companies according to features of the companies participating in the research, was analysed by means of Chi2 (the chi-squared statistic) and V-Cramer. In this research the Chi2 statistics was utilized in the form of contingency tables to hypothesis testing, where the null hypothesis assumes that there is no association between the two variables. In the research the statistical significance in the analyzed cases was lower than 0.05 (p0.05). The hypotheses were prepared during the analysis as an intermediary step and finally they are not included in this paper. V-Cramer is a statistic measuring the strength of dependency, if any, between two categorical variables (number of relations and feature of company) in a contingency table. V-Cramer could be between 0 and 1 and the closer V is to 0, the smaller the association between the variables is. If V is closer to 1, it means a strong association between variables.

Some limitations of the method should be noted. First of all, the structure of the SMTEs sample does not exactly reflect the reality structure of the companies in the Małopolska region, although high participation of micro enterprises could be seen as very valuable. Usually the owners or managers are not interested in participation in scientific research and reject such invitations. Secondly, the dominant part of the sample came from the city and district of Cracow, so the metropolitan area is imperceptibly overrepresented. That could be affected by a well-known good reputation of the Tourism Department of CUE in that area. All those limitations can considered as accepted and allow preparing a statistical analysis and drawing conclusions.

3. LITERATURE REVIEW

Nowadays SMTEs play a very important role on the tourism market in providing tailored products and services to tourists by responding to their high expectations and specific needs (Novelli, Schmitz & Spencer, 2006). As Erkkila stated (2004:23), SMTEs can be compared to ‘life blood of the travel and tourism industry world-wide’ and should be treated as a key player in the destination development process. Among small and medium-sized enterprises with limited resources, cooperation with other firms could be a considerable opportunity to overcome the existing development barriers. The key barriers could be identified as: the cost of technology, financial and human resources, reluctance to change and standardization of tourism services (Buhalis, 2002; Ndou & Passiante, 2005). In particular, relations of managers and entrepreneurs could be seen as a main aspect of cooperation (Crick & Spence, 2005; Kontinen & Ojala, 2010). The specific disadvantage of SMTEs is their size, which could be mitigated by the development of strong collaboration with other actors on the market (Bieger, 2004). All stakeholders in the tourism destination are interdependent in terms of their information access, distribution, supplies, sales and at the same time they are interdependent in relation to others companies in the tourism destination (Ford, Gadde, Håkansson & Snehota, 2003:6).

In recent decades SMTEs faced essential changes in the technological and structural sphere, which forces them to increase innovation and competiveness (e.g. Ndou & Passiante, 2005). All those activities aim at securing the development of the companies and destinations as well. It is a difficult task to secure the increase of the tourism arrivals, because tourism stakeholders are interdependent and differentiated regards their main market segment, their financial possibilities, company size and their development goals. Additionally in most cases they are deprived of a generally accepted leader responsible for the future of the tourism region (Lemmetyinen & Go, 2009).

From the point of view a key word is stakeholders. They are defined as a group or individuals who can affect or who are affected by the achievement of the organisation’s objectives (Freeman, 1984, p. 25). In literature many definitions can be found, which, according to Mitchel et al. (1997), are classified by two dominating dimensions: power and legitimacy. The structure of the stakeholders in the tourism destinations can be understood very widely (Timur & Getz, 2008) as all actors connected through direct and indirect business or social relationships within tourism industry. One of the important groups of stakeholders is tourism firm owners, who operate the most part of the SMTEs (Ateljevic, Milne, Doorne & Ateljevic, 1999). In the study of Getz and Carlen (2000), more than 96 per cent of their respondents were the owners of tourism enterprises. Significant is that the rest of the examined group were members of the family that managed those firms.

The SMTEs owners and/or managers have to overcome the operational and strategic barriers by using available resources. Because their activities are not isolated and independent in the tourism destination’s network, unconsciously they are value creators for tourists (March & Wilkinson, 2009:455). Additionally, there is clear evidence that SMEs activelynetwork (Lee & Mulford 1990; Bryson, Wood & Keeble, 1993; Gilmore et al., 2001; Gilmore, Carson & Rocks, 2006). As an element of a wide network of relations they have to benefit from a wide range of cooperation, but the level of advantages depends, among others, on the number and kind of the relations with other stakeholders. Erkuş-Öztürk & Eraydın (2010) emphasized four essentials kinds of benefits for all stakeholders in the tourism industry from cooperation and network development: reduction of transaction costs, support in avoidance of cost arising, better coordination in policy actions and participation in a decision-process with limited resources.

Many benefits received by SMTEs are related to the density of the network which describes the number of relations connected to the actor. Gulati (1995) identified additional benefits from participation in the tourism stakeholder’s network – namely acquisition of trust and reputation, which, in case of SMTEs, could be a strategic attribute in a long-term development policy in competitiveness and innovation improvement. The sustained relations in case of small and medium-sized firms have to be perceived as strategic resources in terms of intangible assets (Frew & O’Connor, 1999; Denicolai, Cioccarelli & Zucchella, 2010). The central aspect of the network is cooperation among destination organizations, companies, authorities and communities. It is a key condition for sustainable planning and development of the destinations (Bramwell & Lane, 2000), but as well as for successful completion of a tourism project (product launching, new distribution channels creation etc.).

4. RESULTS

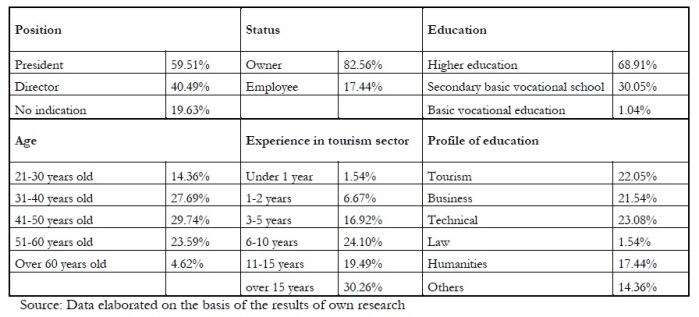

Table 1 shows the basic characteristics of the sample and demonstrates key features of the responders. 97 presidents (CEOs) and 66 directors of the tourism companies participated in the research which constituted 49.74% and 33.85% respectively, of the people who completed the inquiry form. The rest of people did not indicate their position in the company, but they were in the group of responders who classified themselves as the owners of companies. That group consists of 161 persons (82.56%); the remaining responders selected themselves as employees. It was a lower level than the results of the research of Getz and Carlsen (2000), who had owners as 96% of the sample. The largest part of responders was people with significant life experience, because 29.74% of them were between 41-50 years old, 23.58% -between 51-60 years old and 27.69% between 31-40 years old. Also responders could be described as highly experienced tourism businessmen/women, because almost one-fourth have been in the tourism industry for 6-10 years. Almost one fifth have been in the tourism business for 11-15 years and over 30% have been active for over 15 years. A significant part of the researched group has higher education (68.91%) and almost one third graduated from secondary schools (30.05%). A comprehensive range of disciplines is represented in profiles of responders’ education including technology (23.08%), tourism (22.05%), business (21.54%) and humanities (17.44%).

Table 1: Caracteristics of the reponders

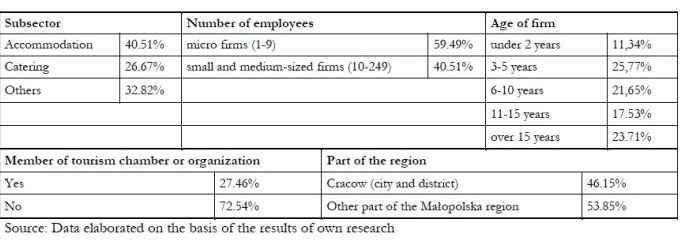

The researched companies sample consists of 40.51% accommodation entities and 26.67% catering companies. Within this group almost 60% were micro enterprises with maximum 9 employees, the rest of participating companies were small and medium-sized enterprises with 10-249 employees. The age of the firm within 3-5 years and over 15 years dominated, and such companies constituted nearly half of the examined companies. Over one fifth of all questioned companies were between 6-10 years old. As we consider the location of the companies, we see significant overrepresentation of the companies from Cracow (understood as the city and district together) – 46.15%. Others companies were located in other parts of the Małopolska region. Very important in the research

was the feature of the membership in the tourism chamber or tourism organizations. As regards this criterion, only 27.46% declared such membership, while others (72.54%) were not members of any tourism chamber or organization (Tab. 2).

Table 2: Caracteristics of the researchd companies from the Malpolska Region

The research into the cooperation area was conducted with emphasis on three features of the companies participating in the study: the level of employment, the subsector of the tourism industry and the age of the company. All analyzed results in Tab. 3 are statistically significant at the level of 1%. That is why collaboration of the examined firms with accommodation, catering, transport companies, private attractions, professional conference organizers (PCO), and marketing agencies was not analyzed in terms of the number of employees. The largest part of micro firms (45%) cooperates with one to five travel agencies; whilst the SMTEs mostly cooperate with a higher number of them (53% cooperate with more than 5 agencies). The largest percentage of the examined micro firms and SMTEs cooperates with maximum five tourist organisations – respectively the half of the micro firms and 59% of the SMTEs. It must to be explained here that tourism associations, tourism chambers and tourism organizations were understood jointly in the study as tourism organizations. Important may be an observation that micro firms do not cooperate to a large extent with any tourism organizations. This figure is significantly higher than in the case of the SMTEs – only 23%. Two thirds of micro firms cooperate with one to five public authorities, whilst only 47% SMTEs cooperate with them. More than half (52%) of micro firms do not cooperate with any university, but 47% of SMTEs cooperate with one to five. Over half of the micro firms (53%) do not cooperate with training or consulting companies, and only one of twenty analysed micro firms (5%) cooperates with more than 5 such companies. Half of the SMTEs cooperate with at least one training or consulting companies (but not more than with five companies). One-fourth of micro firms do not collaborate with any financial institution (bank, leasing or insurance company). Almost three quarters (73%) of the SMTEs cooperate at least with one financial institution (but not more than with five) – Tab. 3.

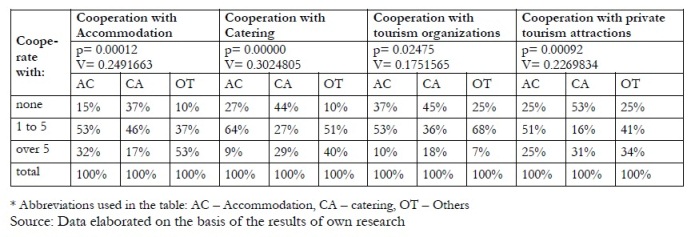

Table 3: SMTE cooperation in relation to the level of employment*

Only four categories of stakeholders were taken for research in relation to the subsector of the examined companies (Tab. 4), namely cooperation with accommodation firms, catering firms, tourism organizations and private tourism attractions. The accommodation and catering companies in the majority of cases cooperate with at least one and not more than five other accommodation companies, respectively 53% and 46%. Other kinds of examined companies cooperate mostly with a greater number of accommodation firms – over half of them (53%) indicated more than five accommodation firms they cooperate with. Important are the results in the event of cooperation between the competitors – nearly one third (32%) of accommodation companies cooperate with their competitors. The situation as regards cooperation with catering companies (restaurants, bars, pubs, etc.) looks differently. Almost two thirds of the examined accommodation companies cooperate with at least one catering firm (but not more than with five), and only 9% of them cooperate with more than five catering firms. The result confirms SMTEs’s need for cooperation, because only 44% of catering companies indicated no cooperation with other catering firms and almost one third declare collaboration with more than five companies which are competitors. A considerable part of catering companies (45%) does not cooperate with tourism organizations, but one-fourth of other firms should be also negatively assessed, because they do not have such cooperation. Although that kind of companies under analysis was negatively evaluated, at the same time they cooperate to the highest degree (68%) with tourism organizations compared to accommodation and catering companies. Half of accommodation firms cooperate with some private tourism attractions (between one to five) and at the same time over half of catering firms do not cooperate with those attractions. Over one third of other kinds of firms collaborate with more than five attractions and 41% with one to five of them.

Table 4: SMTE cooperation in relation to subsector*

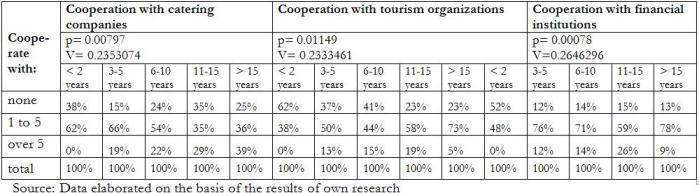

One of the factors that influenced the relations in collaboration is the age of the company. In the research only three categories were statistically significant (at the level of 2.5%) in the following aspects: cooperation with catering companies, tourism organizations and financial institutions. The youngest companies did not manage to build numerous links with catering companies, because over one third (38%) do not cooperate with such kind of partners. We can notice a similar result in the case of 11-15 year old companies – 35%. Two-thirds (66%) of the companies at the age between 3 and 5 years cooperate with one to five catering companies. The results are in conformity with the learning curves, because with time there should be more companies cooperating with at least six catering companies. Cooperation with tourism organizations is not important for almost two-thirds (62%) of the youngest companies, they do not cooperate with such organizations. Half of the companies aged 3-5 years cooperate with one to five companies and only one of twenty examined oldest firms cooperates with more than five tourism organizations. None of youngest firms collaborate with more than five financial institutions and over half of them (52%) do not cooperate with any such institutions. In the case of companies in the range of 3 to 10 years old, over 70% cooperate with at least one such institution (but not more than with five). Almost one-tenth of the oldest companies cooperate with more than five financial institutions – Tab. 5.

Table 5: SMTE cooperation in relation to the age of the company

5. CONCLUSIONS

The results in this paper point to some implications for the tourism policy and strategic planning of some stakeholders. The important issue is to stimulate collaboration of micro firms with tourism organizations. This could be a platform for further development of new businesses and social relations. It is important that tourism authorities support newly established entities whose main problem is to survive in the first two years of existence. One of the solutions could be access to knowledge and information. The specific feature of micro firms is also that they usually cooperate with less than six other sub-sector partners (from among the examined subsectors with the exception of travel agents). Therefore attention of that part of the market should be paid to the quality and content of cooperation rather than to the quantity of collaborating partners. Noticeable is the difference in cooperation with financial institutions between micro firms and SMTEs. As the results show, many accommodation and catering companies pursue co-opetition, i.e. cooperation with traditional competitors. Almost one-third of both studied subsectors cooperate with their competitors on the market – usually at a local or regional level. Catering companies are positioned as an ‘alone wanderer’, because in the examined subsector the largest part of that kind of companies does not cooperate with any other partner in the tourism industry. The research confirmed (not in all cases) that the number of cooperating partners increases with the age of the company.That is why, for further research it is justified to check the reasons of particular levels of the number of links differentiated per subsector and age of the companies.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCE

ATELJEVIC, J., MILNE, S., DOORNE, S., and ATELJEVIC, I. (1999), Tourism Micro-Firms in Rural New Zealand Key Issues for the Coming Millenium, Victoria University Tourism Research Group, Centre Stage Report No.7, School of Business and Public Management, Victoria University, Wellington. [ Links ]

BIEGER, T. (2004), SMEs and cooperation,in Keller, P., and Bieger, T., (eds.)The Future of Small and Medium Sized Enterprises in Tourism, AIEST, St. Gallen, 141-150. [ Links ]

BRAMWELL, B., AND LANE, B. (2000), Collaboration and partnerships in tourism planning, in Bramwell, B., and Lane, B., (eds.)Tourism Collaboration and Partnerships: Politics, Practice and Sustainability, Channel View Publications, Clevedon, 1-19. [ Links ]

BRYSON, J., WOOD, P., AND KEEBLE, D., (1993), Business networks: Small firm flexibility and regional development in UK business services, Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 5(3), 265–277. [ Links ]

BUHALIS, D. (2002), eTourism: Information Technology for Strategic Tourism Management. Pearson (Financial Times/Prentice Hall), London. [ Links ]

CHETTY, S., AND HOLM, D.B. (2000), Internationalisation of small to medium-sized manufacturing firms: a network approach, International Business Review, 9(1), 77-93. [ Links ]

CRICK, D., AND SPENCE, M. (2005), The internationalisation of high performing UK high-tech SMEs: A study of planned and unplanned strategies, International Business Review, 14(2), 167–185. [ Links ]

CSO. (2009), The Structural Changes of the Entities of the National Economy in MalopolskaVoivodship in 2008,Central Statistical Office, Cracow (in Polish). [ Links ]

CSO. (2010), Business Activities of Enterprises with up to 9 Employees in 2009,Central Statistical Office, Warsaw (in Polish). [ Links ]

DENICOLAI, S., CIOCCARELLI, G., AND ZUCCHELLA, A. (2010), Resource-based local development and networked core-competencies for tourism excellence, Tourism Management, 31(2), 260-266.

ERKKILA, D. (2004), Introduction to Section 1: SMEs in regional development, in Keller P. and Bieger T., (eds.)The future of small and medium sized enterprises in tourism, AIEST 54th Congress, Petra Jordan, 23–34. [ Links ]

ERKUS-ÖZTÜRK, H., AND ERAYDIN, A. (2010), Environmental governance for sustainable tourism development: Collaborative networks and organisation building in the Antalya tourism region, Tourism Management, 31 (1), 113-124. [ Links ]

FORD, D., GADDE, L. E., HÅKANSSON, H., AND SNEHOTA, I. (2003), Managing relationships, Wiley, Chichester. [ Links ]

FREEMAN, E.R. (1984), Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach, Pitman, Boston, MA. [ Links ]

FREW, A., AND OCONNOR, P. (1999), Destination marketing system strategies in Scotland and Ireland: an approach to assessment, Information Technology and Tourism, 2(1), 3-13. [ Links ]

GETZ, D., AND CARLSON J. (2000), Characteristics and goals of family and owner-operated business in the rural tourism and hospitality sector, Tourism Management, 21, 547-560. [ Links ]

GILMORE, A., CARSON, D., AND ROCKS, S. (2006), Networking in SMEs: Evaluating its contribution to marketing activity, International Business Review, 15, 278-293. [ Links ]

GILMORE, A., CARSON, D., AND GRANT, K. (2001), SME marketing in practice, Marketing Intelligence and Planning, 19(1), 6– 11. [ Links ]

GULATI, R. (1995), Does familiarity breed trust? The implications of repeated ties for contractual choice in alliances, Academy of Management Journal, 38, 85-112. [ Links ]

KONTINEN, T., AND OJALA, A. (2011), Network ties in the international opportunity recognition of family SMEs. International Business Review, 20 (4), 440-453. [ Links ]

LEE, M. Y., AND MULFORD, C. L. (1990), Reasons why Japanese small businesses form co-operatives: An exploratory study of three successful cases, Journal of Small Business Management, 28(3), 62–71. [ Links ]

LEMMETYINEN, A., AND GO, F.M. (2009), The key capabilities required for managing tourism business networks, Tourism Management, 30, 31-40. [ Links ]

MARCH, R., AND WILKINSON, I. (2009), Conceptual tools for evaluating tourism partnerships, Tourism Management, 30(3), 455-462. [ Links ]

MITCHELL, R.K., AGLE, B.R., AND WOOD, D.J. (1997), Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: defining the principles of who and what really counts, Academy of Management Review, 22(4), 853-86. [ Links ]

MORRISON, A. (1998), Small firms co-operative marketing in a peripheral tourism region, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 10(5), 191-197. [ Links ]

NDOU, V., AND PASSIANTE, G. (2005), Value creation in tourism network systems, Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism, 14, 440-451. [ Links ]

NOVELLI, M., SCHMITZ, B., AND SPENCER, T. (2006), Networks, clusters and innovation in tourism: A UK experience, Tourism Management, 27, 1141-1152. [ Links ]

PAGE, S.J., FORER, P., AND LAWTON, G.R. (1999), Small business and development and tourism: terra incognita?,Tourism Management, 20, 435-459. [ Links ]

TIMUR, S., AND GETZ, D. (2008), A network perspective on managing stakeholders for sustainable urban tourism, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 20(4), 445-461. [ Links ]

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The scientific research financed from the budget for science in 2009-2011 as a research project.

Submitted: 20.07.2011

Accepted: 25.09.2011