Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Vista. Revista de Cultura Visual

versión On-line ISSN 2184-1284

Vista no.13 Braga jun. 2024 Epub 30-Jun-2024

https://doi.org/10.21814/vista.5525

Thematic Articles

Armando de Almeida. A Lesson in Resistance in Portuguese Running Culture

1 Instituto de Investigação em Design, Media e Cultura, Faculdade de Belas Artes, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal

2 Instituto de Investigação em Arte, Design e Sociedade, Faculdade de Belas Artes, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal

Em março de 1913, Armando de Almeida venceu a maratona da “Semana Desportiva” do jornal O Mundo. Em maio do mesmo ano repetiu a proeza ao vencer a maratona dos Jogos Olímpicos Nacionais, na altura, a mais importante competição de atletismo no país. Por essas vitórias, é considerado o campeão nacional da maratona para o ano de 1913 pela Federação Portuguesa de Atletismo. Recordemos que a Federação Portuguesa de Atletismo só existe formalmente desde 1921. É, conjuntamente, num contexto de grande perturbação político-social e num ecossistema elitista, programaticamente desestruturado, que Armando de Almeida se destaca do grupo matricial de atletas que tomavam parte nestas novas formas de lazer e demonstrações de cultura de massas - as corridas pedestres de longa distância. A sua presença ativa na cultura de corrida da metrópole é contemporânea com a origem e constituição do movimento negro (1911-1933) - pioneiro no combate político antirracista em Portugal.

Neste texto, que tem como ponto de partida o resgate de fotografias e narrativas dos primórdios da história e da memória do atletismo português, procuramos biografar Armando de Almeida, num exercício simultâneo de empatia e militância como contributo para o debate, contrariando invisibilidades consequentes de negligências historiográficas. Tentamos, também, reconstituir a possibilidade de articulação entre os percursos emancipatórios do atleta com a organização de movimentos políticos e sociais no tumultuoso momento histórico da Primeira República, numa capital de império colonial, com expressiva presença de pessoas afrodescendentes, esse fenómeno histórico plurissecular.

Palavras-chave: Armando de Almeida; antirracismo; arquivo; cultura de corrida; cultura visual

In March 1913, Armando de Almeida won the "Semana Desportiva" (Sports Week) marathon organised by the newspaper O Mundo. In May of the same year, he repeated the feat by winning the marathon at the National Olympic Games, then the most important athletics competition in the country. For these victories, he is considered the national marathon champion for 1913 by the Federação Portuguesa de Atletismo (Portuguese Athletics Federation). It is worth noting that the Federação Portuguesa de Atletismo only formally existed in 1921. Against the backdrop of significant political and social upheaval and within an elitist and largely unstructured ecosystem, Armando de Almeida stood out among the core group of athletes participating in these new forms of leisure and mass cultural demonstrations - long-distance pedestrian races. His active involvement in the running culture of the metropolis coincided with the emergence and growth of the Black movement (1911-1933) - which pioneered political activism against racism in Portugal.

This text delves into the recovery of photographs and narratives from the early days of Portuguese athletics, aiming to biograph Armando de Almeida. Through an exercise of empathy and activism, it contributes to the debate, counteracting historical oversights and invisibilities. Additionally, it attempts to reconstruct the connections between the athlete's emancipatory endeavours and the organisation of political and social movements during the turbulent period of the First Republic. Set in the capital of a colonial empire with a notable presence of people of African descent, it explores this centuries-old historical phenomenon.

Keywords: Armando de Almeida; anti-racism; archive; running culture; visual culture

1. Introduction/Framework

In the centre of the photograph, we see a young-looking Black man running on what looks like a dirt athletics track through a crowd of people, a kind of "spectator-actors" (Figure 1).

Identified by the stencil-inscribed number 20 on the chest of a shirt that we recognise as one of the official Sporting Club de Portugal (SCP) outfits in the early 1910s, the young man carries a crumpled bucket hat with wide brims made of malleable fabric in his left hand. Within the surrounding crowd, there is a spectrum of reactions: some applaud and move alongside the athlete, others celebrate but remain still, some appear indifferent, while others watch with apprehension or draw the photo reporter's attention to the moment the athlete passes. Clearly visible are the brick walls delineating the "stadium space", a privileged place to watch sports competitions. Additionally, several posters in the background catch the eye, including those advertising a bullfight and possibly NSU machines - potentially bicycles, motorbikes, or cars. Notably, a child with bare feet is immobilised near the right edge of the frame, a figure that has been recurrent in photographs spanning Portuguese history, both in rural and urban contexts, as Manuela Hasse (1999) recalls:

many of the men and women who were born, grew up and died in Portugal ( ... ) had not had the opportunity to experience conditions of existence other than adversity and hardship. For this reason, they became adults learning from an early age to face all kinds of difficulties, misery and illness, expecting nothing, adapting to everything, to setbacks, deprivation and misfortune as if these were, after all, the natural conditions of existence. (p. 22)

This photograph was retrieved directly from a silver gelatin glass negative1, discovered within a collection of 71 boxes of negatives owned by the family of photographer Arnaldo Garcez. Garcez was one of the key figures during the emergence and "consolidation of reportage photography and the establishment of the image as the focal point of news, through illustrated newspapers" (Tavares, 2010, p. 406).

A reproduction of the photograph mentioned can be viewed on the front cover of the illustrated magazine Tiro e Sport, Issue 507, March 31, 1913, featured in Figure 2, with the caption: "the winner of the Marathon arriving at the finish line" ("Semana Desportiva do 'Mundo'", 1913). This image is part of a series of four photographs credited to Arnaldo Garcez, this time reframed, making the barefoot child invisible2. These photographs are part of the reportage covering what, based on a comprehensive analysis of various periodicals from that time, we believe to have been the most significant sporting celebration in Portugal in 1913, the "Sports Week" promoted by the newspaper O Mundo, held in Lisbon in March from 9 to 16.

From “Semana Desportiva do ‘Mundo’”, 1913, Tiro e Sport, (507), p. 1

Figure 2: "Semana Desportiva do 'Mundo'", 1913, photographs by Arnaldo Garcez

On the front page of the newspaper O Mundo, Issue 4497, of March 17 1913, the same runner with the number 20 on his chest is depicted sitting on a bench, holding a trophy on his lap (Figure 3). The caption reads: "the winner of the Marathon race, who was awarded the 'World' Cup" ("A Semana Sportiva do 'Mundo'", 1913). The race took place the day before this news piece.

From “A Semana Sportiva do ‘Mundo’”, author not identified, e “Notas á Margem”, by M. Garção, 1913, O Mundo, (4497), p. 1

Figure 3: “A Semana Sportiva do Mundo” and “Notas á Margem”, 1913

Both the photograph and the text are unidentified. It reads:

- They are coming! - They've reached Lumiar! And once again, the whole crowd stirs with anxious curiosity. ( ... ) firecrackers burst out, and the winner has indeed arrived. It's A. de Almeida, a Black man, a member of the Sporting Club, who enters in excellent spirits, circling the pitch with the same stride as he left. Applauses erupt from everywhere. The winner is celebrated with ovations. The crowd cannot contain itself and invades the arena. The fencing has to stop. The winner is escorted to the tribune of honour, where the President of the Ministry presents him with the World Cup. At this point, Mr Almeida received another ovation and then went to the Sporting Club headquarters, offering his prize to the board of directors . ("Uma Tentativa Coroada de Exito", 1913, p. 1)

Also featured on the front page is a column signed by Mayer Garção (1913), titled "Notas á Margem" (Side notes), wherein we read:

yesterday's winner, ( ... ), was a Black boy. A Black boy of modest condition, weak in appearance, was the winner of the competition in which a few dozen Whites participated. A large audience, made up of Europeans, Whites and all social classes, enthusiastically cheered the winner, who was presented with the prize by the head of the Portuguese government. There was not a protest, not a whistle, not a deprecating smile. The winner was acclaimed and consecrated as if he were White. There was not the slightest discrepancy of opinion, no bitterness, no sarcasm. Here is a fact that at first glance would seem to be of no particular importance, and yet it is, and very important. Despite the advanced stage of world civilisation, race prejudice still exists in countries that consider themselves the most advanced. The colour of the face is still a sign of caste superiority or a stigma of human inferiority. ( ... ) In other countries, where race hatred does not reach that extreme, the Black man is still an object of contempt and derision. The fact that yesterday an entire audience only clapped, sympathised and gave ovations to the Black winner and that it was a Portuguese audience, with all classes and the head of government himself joining in these demonstrations of justice, lifts us in our own eyes, demonstrates that we are a society that is committed to the principles of democracy, which is based on this justice, and proves, once again, that there are no few peoples when these peoples know how to overcome prejudices, superstitions and intolerances rooted in savage traditions and practices. We are small, but we understand freedom; we are small, but we understand justice; we are small, but we understand progress. And that is why the feeling of equality and human fraternity is not only proclaimed in words but in every opportunity that events give us. (p. 1)

The lengthy quotation from 1913 is justified as it reveals a form of "generic lusotropicalism" (Cardina, 2023, p. 31), which predates and persists beyond Gilberto Freyre's influence. It exposes multiple layers of contradictions that become entrenched in the romanticised narrative of the Portuguese as "least bad coloniser" and "least racist", fostering a perception of greater dialogue. "Lusotropicalism", this "quasi-theory" of the Portuguese relationship with the tropics (Castelo, 2013), a "kind of non-colonial colonialism" (Cardina, 2023, p. 166), the set of narratives that downplays the extent of violence and allows for the denial of structural and systemic racism, widely sponsored by the Estado Novo dictatorship regime, and which has become ingrained in the national hegemonic apparatus and mindset, even today, repeatedly propagated in a transversal and intergenerational way, extending to the highest figures in the national political and media space (Cardina, 2023; George, 2023).

In this excerpt, the reference to the United States of America, where racial segregation was still legalised with public lynching as a daily practice, seems equally evident, and it is in this confrontation, upon delving into this text, that a new spiral of questions arises: could Garção also be referring to other countries? The United Kingdom? France? The Netherlands? Belgium? Germany? Any colonial empire could be targeted. Nevertheless, what it crystallises is the idea of Portugal as an advanced country in terms of human rights. Despite the assertion of a diverse audience in terms of social backgrounds, the text assumes it to be predominantly "European and White", perhaps adhering to a "symbolic system, [where] the complexity of the Portuguese is opposed to the simplicity of the Blacks" (Cabecinhas, 2007, p. 59). This narrative unfolds just a few decades before the self-serving declaration of the "vitality of Portuguese multiracialism" (Cardão, 2020, p. 356).

The same photograph with Armando de Almeida holding the trophy is featured on Page 4 of Os Sports Illustrados, Issue 143, March 22 1913. This publication also covers the marathon of the newspaper O Mundo's "Sports Week" (Figure 4), now credited to Augusto Rato (“Semana Sportiva do ‘Mundo’”, 1913)3.

From “Semana Sportiva do ‘Mundo’”, 1913, author not identified, Os Sports Illustrados, (143), p. 4

Figure 4: Set of four photographs of four Semana Desportiva champions, 1913, photographs by Augusto Rato

In Os Sports Illustrados, Number 150, of May 10 1913 (Figure 5), the (same) photograph is presented with the title "O Negro Invencível" (The Invincible Negro; 1913) and the caption: "winner of the annulled Marathon race". This announcement pertains to the marathon of the National Olympic Games, originally held on May 4 1913, which the organisers, the Sociedade Promotora de Educação Physica Nacional4, annulled due to irregularities along the course. It was rescheduled for 14 days later, on the 18th of the same month, and Armando Almeida won on both occasions5. The title "O Negro Invencível" (1913) refers to the mediatisation of the athlete through phenotypical reification. Armando de Almeida is dehumanised in his portrayal, objectifying him as the "negro", not as a person, not as an athlete, not even using the most common terminology of the time - the sportsman.

From “O Negro Invencivel” and “Um Grande Atléta”, author not identified, 1913, Os Sports Illustrados, (150), p. 4

Figure 5: Armando de Almeida and Armando Cortesão, 1913

Language, as Stuart Hall (2003) highlighted, always holds significance, serving as the conduit through which we construct meaning and achieve representation. On the same page (Figure 5), on the right-hand side, a photograph captures Armando Cortesão in a triumphant stance, accompanied by the caption "Um Grande Atléta" (A Great Athlete; 1913). Armando Cortesão6 was one of the most prominent figures in the advent of sports in Portugal7. Despite a two-month gap between the events depicted in Figure 4 and Figure 5, the photographs depicting Armando de Almeida and Armando Cortesão are the same, printed with the same scale and the same layout.

Coming across a photograph in the press, which does not always accurately depict the advertised event, prompts reflection on a concept discussed by David Campany and Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa (2022), which is the realisation that photographs often have mysterious and chameleon-like relationships with their contexts. When observing a photograph reproduced on a page, for example, it is uncommon to consider it as misplaced or belonging elsewhere. Still, in the case of repetition, it resembles an exercise, albeit with apparently different premises to those that guide this work, carried out by Su Braden (1983) in "Committing Photography",

who controls a photograph? Is it the photographer, or the subject, or the manufacturer of the camera or film? Or is it the publisher and distributor? The question sets one off on a trail as rife with conflicting clues as a good detective story. The final twist includes the inevitable re-examination of the original question. It makes more sense if we ask, "who could control the photograph?". (p. 19)

In the media space of Portuguese mass culture, it was not until the 1960s and particularly the 1970s, as noted by Marcos Cardão (2020), that we witnessed the emergence of prominent figures from the African territories colonised by Portugal. Examples include celebrated football stars, luminaries in light music, and participants in popular beauty pageants.

Tiro e Sport, Issue 512, June 1913, features an opinion piece with the title “Depois de Repetida a Corrida da Marathona É Rijamente Disputada e Decorre com Toda a Regularidade” (After the Marathon Race Is Repeated, It Is Keenly Contested and and It Takes Place With All Regularity; Moreira & Rosado, 1913), preceded by the headline "National Olympic Games", in Figure 6 (both pages). The centre of the first page shows a blurred image that is a photomontage (Figure 7), in which the athlete is depicted cut out and placed in superimposition on the left edge of the reproduction. The SCP emblem is visible on the athlete's attire, along with the prominently displayed number 43. The athlete appears to have strips of fabric wrapped around each hand, a common feature observed in other athletes in photographs from that period. Moreover, he is wearing a wide-brimmed bucket hat on their head.

From "Depois de Repetida a Corrida da Marathona É Rijamente Disputada e Decorre com Toda a Regularidade", by C. Moreira and C. Rosado, 1913, Tiro e Sport, (512)

Figure 6: National Olympic Games, 1913

In the background, we can see the group of athletes lined up for the start. Armando de Almeida is positioned on the left edge of the group. We can also see the crowd on the right, and the cyclist, who is riding ahead of the same athletes, is possibly one of the race officials, as he is the only person moving. The photo's caption reads: "marathon competitors, winner E. de Almeida on the left". The printed piece dedicated to the race spans two pages and is divided into two parts. The first part is a text signed by Corvinel Moreira; the second introduces and reproduces in full a report by Carlos Rosado. Further details about this first part and its author will be discussed later. Proceeding to the report, transcribed in full, about the organisation of marathon races (in the plural). Carlos Rosado, "Secretary of the Organising Committee", sent by the Sociedade Promotora de Educação Physica Nacional, confirms Armando de Almeida, "runner with the number 43", as the winner, with a finishing time of around 2 h and 58 min. In this report, we can read the official explanation for the annulment of the first race:

the Marathon race was first held on May 4 1913. However, it was annulled due to the competitors deviating from the established course, as they failed to adhere to the respective regulations and plan (...). Consequently, the race was repeated on the 18th of the same month, with a general adherence to all the articles of the regulations. (Moreira & Rosado, 1913, paras. 6-7)

This excerpt provides a technical explanation for the annulment of the race on May 4 and its repetition two weeks later. Although it lacks specific details about the sporting event itself, it clarifies the circumstances surrounding the cancellation and subsequent validation of the race, indicating full compliance with regulations during the repetition. No information has been provided as to whether any athletes completed the distance of the race. Two weeks is always too short a time to recover from a race as gruelling as a marathon. Two possible hypotheses emerge: either there was no debate and, consequently, no consensus on the matter, or the race had to be rescheduled within that timeframe due to calendar constraints. It is plausible that both hypotheses hold some truth.

Returning to the first part of the article dated June 15, 1913, signed by Corvinel Moreira, the official doctor of the competition, he describes how he agreed to organise the medical services for the "Sports Week" of the newspaper O Mundo and to write about the races he attended at the request of Carlos Trilho8. In the same text, he expresses his disfavour of the marathon race and his belief that none of the athletes who participated were physically prepared for the exertion the race requires,

I confess that this race does not earn my sympathy, as I believe that after such an effort, any heart, no matter how strong, will inevitably struggle to some extent. As for the runners, I must say that all of them, whether winners or losers, were ill-prepared for the race they were about to undertake ( ... ). I apologise for these small observations, and I expect them again next year, but then I hope to have to say only good things. (Moreira & Rosado, 1913, paras. 4-5)

The sole mention he makes regarding the winner's performance is encapsulated in the sentence: "it is fair to confess that E. A. de Almeida, the winner, was reasonably prepared and that is the only reason he won" (Moreira & Rosado, 1913, para. 5). This statement seems to us to lack scientific rigour.

O Mundo, Issue 4499, dated March 19, 1913, on Page 3, features a column titled "Semana Sportiva do 'Mundo'. Depois das Provas" (1913) (‘Mundo's’ Sports Week. After the Races). In this column, there is a photograph of Doctor Corvinel Moreira9, accompanied by the following description: "to Dr. Corvinel Moreira, who established an exemplary medical service not only along the course but also during the Marathon" ("Semana Sportiva do 'Mundo'. Depois das Provas", 1913, p. 1).

António dos Anjos Corvinel Moreira served as a naval medical officer until his passing in 1932, during which time he held the position of director of the Night Aid Posts. Throughout the 1910s and 1920s, he held various executive roles in the Lisbon City Council, beginning with the first local elections following the establishment of the Republic in 1913. An ardent Republican and Freemason, he was a member of the Grande Oriente Lusitano Unido, Supremo Conselho da Maçonaria Portuguesa. On the recommendation of the minister of the Navy, he was conferred the rank of knight of the Military Order of Saint James of the Sword in 1921. In 1925, he was listed as a candidate on two lists for Lisbon City Council, in a coalition between the Portuguese Republican Party and the Portuguese Socialist Party, while also being listed with the Free Men. This practice, allowing candidates to appear on multiple lists, aimed to increase votes by doubling their presence on ballots and potentially garnering more votes. That seemed to be a common practice, not exclusive to Corvinel Moreira (Relvas, 2014). Therefore, Corvinel Moreira was a figure with high social capital, closely tied to political influence. Given his connections, Corvinel Moreira's perspectives likely emanated from this position, which is a position of power, a social and political power in the largest and most influential urban centre in the country. A city in turmoil and undergoing rapid transformations as a result of a certain "revolutionary conjuncture" (Rosas, 2010, p. 15). Moreover, individuals with the ability to shape the media narrative and wield influence over public opinion held considerable power during this time.

Trying to grasp the political history and the political figures in the municipality of Lisbon during the First Republic is also an endeavour to understand the evolution and modernisation of citizenship practices in the country. We contend that compiling this information also contributes to the inter-relational contextualisation of the environment and the socio-political ecosystem over those years, involving a broad spectrum of agents10.

We acknowledge the absence of sustained efforts to safeguard, narrate, reconstruct, and reconsider the history and memory of Armando de Almeida's tenure in national athletics. Understanding how a significant champion can be rendered invisible is, to some extent, an effort to counteract "the recurrence of the exclusionary impacts of the major modern scientific and historical narratives" (Silva, 2007/2022, p. 72). Moreover, it involves understanding who has the power to write the moments that can define our social memory and our collective memory. Examining this report, we posit that Corvinel Moreira, a physician and naval officer, was a supporter of physical education but antagonistic to the sports movement.

The newspaper A Capital, Issue 2868, dated August 15, 1918, features the announcement of Almeida's death: "the great Portuguese runner Armando d'Almeida has died. ( ... ) Admitted to Rêgo hospital11, where he had been admitted only three weeks ago" ("Morte do Corredor Portuguez Armando d'Almeida", 1918; Figure 8). This mention identifies Armando de Almeida as the winner of the marathon at the National Olympic Games and O Mundo's "Sports Week" in 1912, although the correct information should be 1913. While this discrepancy could be a mere typo, it is noteworthy that 1912 was the year Francisco Lázaro won the marathon and qualified for the Olympic Games in Stockholm. As he was hospitalised for three weeks at the Hospital do Rêgo, a hospital for infectious diseases, it was initially assumed that his passing was related to an illness associated with the pneumonic fever pandemic that was ravaging the world at the time.

From “Morte do Corredor Portuguez Armando d’Almeida”, author not identified, 1918, A Capital, (2868), p. 2

Figure 8: Armando de Almeida's death announcement in A Capital

The final paragraph of the announcement extends condolences to the athlete's family, as well as to the clubs he represented, Sport Club Cruz da Pedra and SCP. So far, we have been unable to find any relatives. All the information contained in the set of 25 sheets made available by the Documentation and Archive Division of the General Secretariat of the Ministry of Internal Affairs indicates that Sport Club Cruz da Pedra was dissolved in 1938. The same documentation does not include any information directly related to athletes.

The SCP archives department did not respond to our direct inquiries regarding Armando de Almeida. However, there is a Wiki Sporting page containing the following information:

Armando Almeida was the National Marathon Champion in 1913, winning this race at the National Olympic Games, which were at the time the Athletics competition the time and was recognised by the Portuguese Federation of this sport for awarding the title of Champion of Portugal between 1910 and 1913. That same year, he also won the Sports Week Marathon organised by the newspaper "O Mundo". In 1914, he secured the eighth position in the Marathon at the National Olympic Games, contributing to SCP's victory in the team classification. (Armando Almeida, n.d., paras. 1-3)

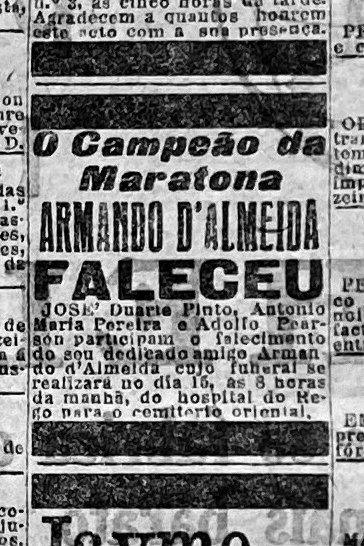

The announcement of Almeida's death also features on Page 3 of Diário de Notícias, Issue 18948, of August 14, 1918 ("O Campeão da Maratona Armando d'Almeida Faleceu", 1918; Figure 9). With little information, we learned that it had been "attended" by José Duarte Pinto, António Maria Pereira12, and Adolfo Pearson. We have not been able to find any significant information about these three "dedicated friends" relevant to Almeida's biography.

From “O Campeão da Maratona Armando d’Almeida Faleceu”, author not identified, 1918, Diário de Notícias, (18948), p. 3

Figure 9: Armando de Almeida's death announcement in Diário de Notícias

In Figure 10, sourced from Arnaldo Garcez's family collection, the glass negative exhibits significant decay. Nevertheless, it is possible to identify José Salazar Carreira, representing the SCP, unambiguously "with the lion on his chest", competing in a speed race with a member of the Club Internacional de Football. At the time, they were the foremost elite clubs in the capital.

Arnaldo Garcez

Figure 10: José Salazar Carreira crosses the finish line, sourced from the family collection of Arnaldo Garcez

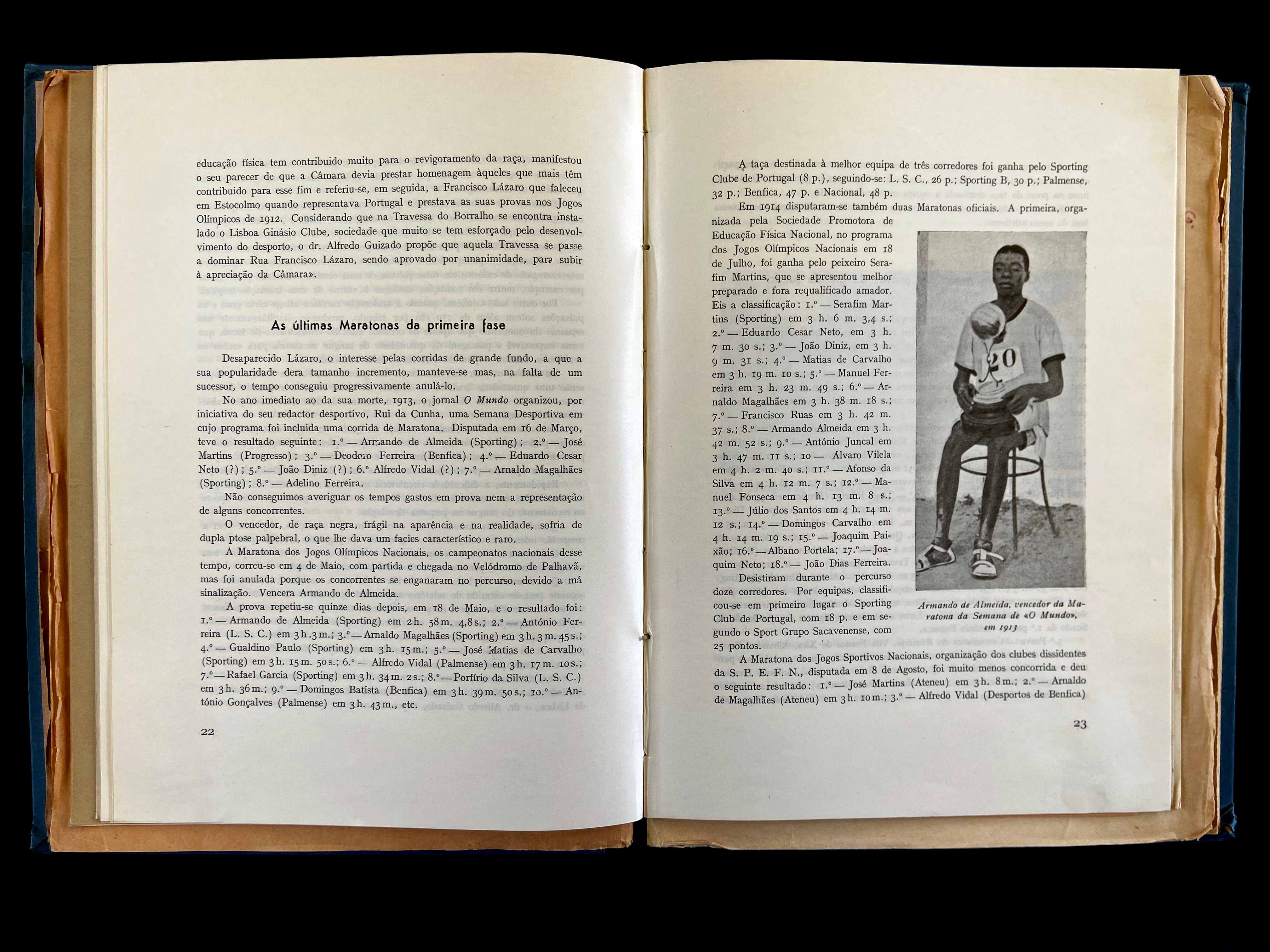

The history of SCP, the Portuguese Athletics Federation, the Confederation of Sports, and the Portuguese Olympic Committee are frequently interconnected. Salazar Carreira was associated with all these entities from 1911 to 1964, holding significant roles within each. As a sports inspector, he published an article entitled "A Corrida de Maratona na História do Atletismo Português em 1949" (The Marathon Race in the History of Portuguese Athletics in 1949; Carreira, 1949). Within this article, he dedicates two pages to the marathons of 1913 and 1914 (refer to Figure 11).

From "A Corrida de Maratona na História do Atletismo Português", by J. S. Carreira, 1949, Boletim da Direcção Geral de Educação Física, Desportos e Saúde Escolar, pp. 22-23

Figure 11: "The Last Marathons of the First Phase", double page

In his writing, Salazar Carreira (1949) described Armando de Almeida as: "of Black race, fragile in appearance and, in fact, suffering from double eyelid ptosis, giving him a characteristic and rare appearance" (p. 22). On the same page, he confirms that Armando de Almeida won the official marathons held in Portugal, including the race on May 4 of that year and that the race "was annulled because the competitors took the wrong route due to poor signposting" (p. 22). The accompanying image in Salazar Carreira's 1949 text depicts Armando de Almeida with the trophy from the "Sports Week" of the newspaper O Mundo in 1913. Notably, Salazar Carreira (1949) chose Armando de Almeida, and this photograph in particular, to accompany the two pages he devoted to what he called the "last marathons of the first phase" (p. 22). This choice necessarily meant excluding Serafim Martins, the winner of the 1914 "Portuguese Marathon”.

Could this be the only photograph available to Salazar Carreira for reproduction? Could it be the one that best showed the physical description of Almeida, which Salazar Carreira seemed to wish to emphasise?

The photograph consistently appears blurred, suggesting that it was out of focus in the original matrix. Armando de Almeida is depicted seated, holding a trophy on his lap. The trophy bears a resemblance to football trophies, with a spherical element at the top that mirrors the appearance of stitched leather strips commonly used in footballs until the introduction of 32-panel balls in the “1970 FIFA World Cup”.

We found very few sources on Armando de Almeida in the archives. However, we managed to trace Almeida's participation in road races dating back to 1910, consistently achieving prominent positions. His involvement continued until the 1914 National Olympic Games, where he finished eighth in the marathon with a "gruelling" time of 3 h and 42 min (Carreira, 1949; Jornal de Sport, 1914). Officially, all athletics activities came to a halt between 1915 and 1922, so there is no evidence of any other marathons until 1936 (Carreira, 1949; Fernandes, 2010). Surprisingly, Carlos Paula Cardoso (2001) does not refer to Armando de Almeida (or Serafim Martins13, another prominent athlete of the time) in his História do Atletismo em Portugal (History of Athletics in Portugal). This omission is striking given the ambitious title of the history, which overlooks two of the most important figures in the early years of the discipline in Portugal.

2. Crossroads/Transcendence

Research teams focusing on the historiography of sports practices, human motor skills, and even athletics in Portugal rarely mention Armando de Almeida. When they do, the references are usually brief and vague, with little to no accompanying illustration. On this journey, we frequently recalled the insights of Luíz Trancendência Antônio Simas, who suggests that "people often mistake crossroads for labyrinths. A labyrinth is where you are unsure how to get out. But a crossroads is a destination; it holds a sense of transcendence; it is tied to the notion of encounter" (Zaccaro & Carneiro, 2020, para. 8). Acknowledging the constraints of our investigation, we sought clues in alternate archives. Cláudia Castelo (2022) affirms:

studies dedicated to the origins of African nationalism and the dissemination of anti-colonial and anti-racist ideas and texts ( ... ) are situated within the realms of intellectual or political history, often highlighting figures and groups that already possess some level of visibility. Even when they explore aspects of social interaction, they still refer to elites. (para. 3)

Cristina Roldão et al. (2023), delving into what they describe as a "plunge into a silenced history" (p. 13), have "retrieved from the past the importance of the Black population in the political, social, and cultural transformation of Portuguese society" (p. 3). They examine "the first politically organised Black movement in Portuguese history" (Varela & Pereira, 2020, p. 3), primarily focusing on the period spanning from 1911 to 1933, during which they identify 11 "Black press" publications. Given the overlap in the timeframe of our research, we pursued the leads they presented, and it was within one of these publications that we came across the same photograph along with new insights into Armando de Almeida.

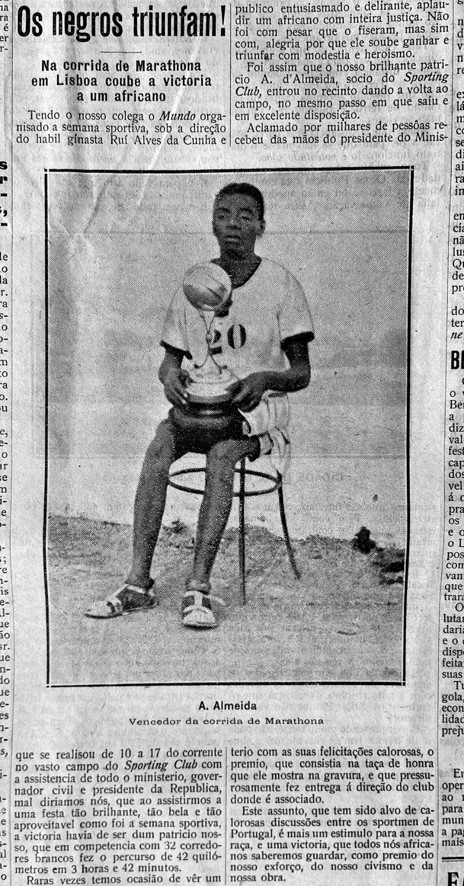

On the front pages of the newspaper A Voz D'África, Issue 15, dated April 1, 1913 (Figure 12), we discovered prominent mentions of Armando de Almeida's victory. The headline "Viva a Raça Negra" (Long Live the Black Race) graces the first page, accompanied by a text lauding Armando de Almeida's accomplishment. In this piece, the unidentified author reveals that the athlete is a "son of Angola"14 - a detail we speculated might provide insight into Almeida's birthplace. Alongside the text on the second page is a photograph of the athlete seated with the trophy on his lap ("Os Negros Triunfam", 1913; Figure 13). In this rendition, Armando de Almeida's figure appears less retouched. Although the printing points are noticeable, the facial expression seems sharper compared to other reproductions.

From "Os Negros Triunfam", author not identified, 1913, A Voz D'Africa, (15), p. 2

Figure 13: Armando de Almeida on “Black press”

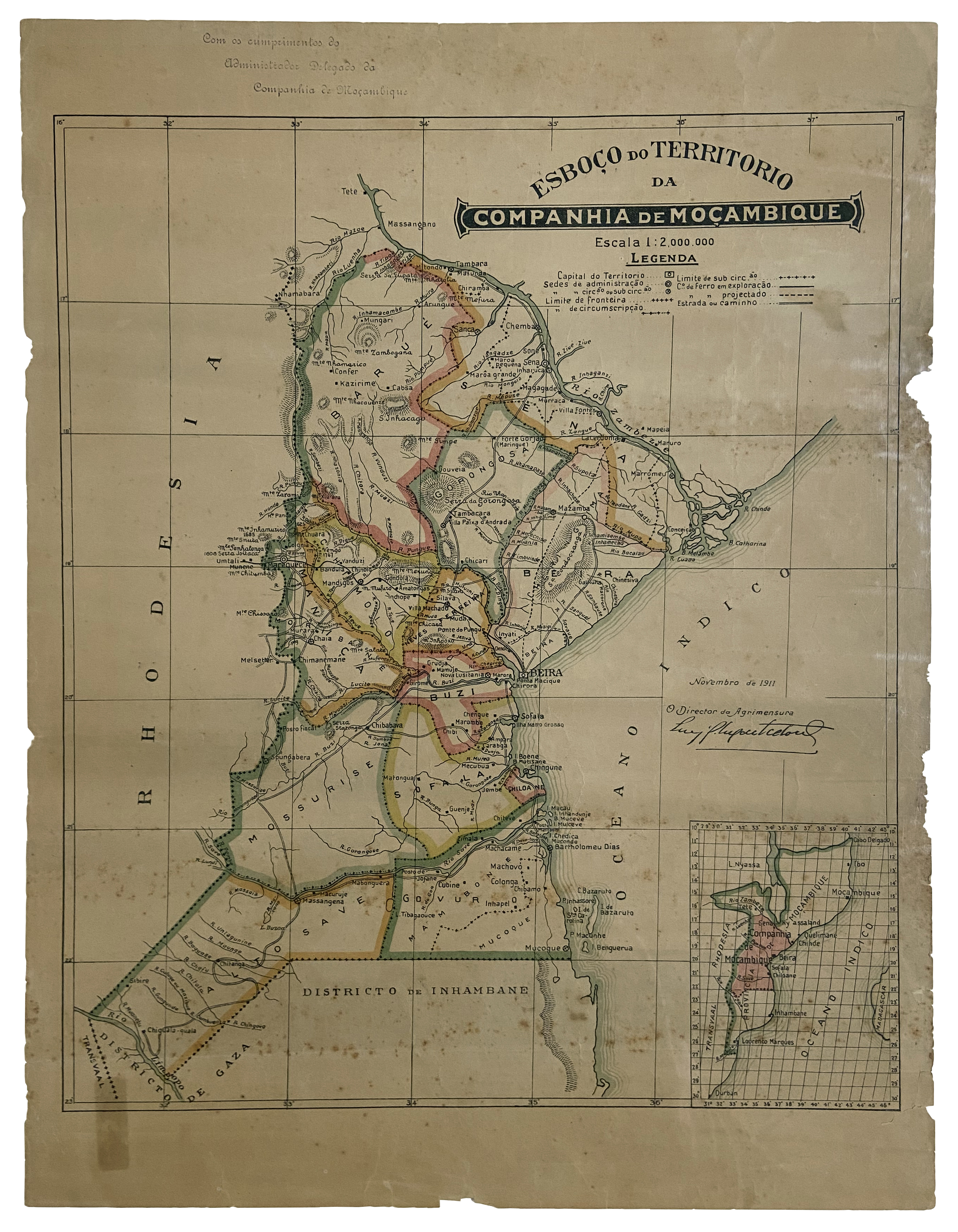

Just when we thought we had solved a biographical detail, we read Armando de Almeida's death record (Figure 14), sourced from the National Archives of Torre do Tombo, kindly shared by Cláudia Castelo. In addition to confirming his passing on August 13, 1918, at the Hospital do Rêgo due to pulmonary tuberculosis15 at the age of 24, the record reveals that he was "born in Gorongosa, province of Mozambique, Portuguese East Africa". The same document also shows that he was employed as a "labourer" and that the informant of the death was unaware of his parentage. His residence was documented as the first floor of Number 22 Estrada da Palhavã16 in Lisbon. While this discovery may not seem to contain particularly pertinent details, the most intriguing revelation is that Armando de Almeida was born in Gorongosa, an area situated on the southern edge of the Great Rift Valley17 in the central region of Mozambique. Considering that he passed away at the age of 24, his birth year would have been around 1894-1895, presumably before the seizure of Ngungunhane on December 28 1895. Anticipating the idea we will elaborate on next, it is noteworthy to mention that this discovery leads us to a statement by Denise Ferreira da Silva (2007/2022), "the subject may be dead ( ... ), but his ghost - the tools and the raw material used to assemble him - remains with us" (p. 36).

"Gorongosa" is believed to be the Portuguese name for "Kuguru Kuna N'gozi", which translates to "there is danger up there"18. In 1898, Matheus Augusto Ribeiro de Sampaio described the territory:

besides the vast plains stretching as far as the eye can see to the south, east, and north, the central and western parts feature mountains that rise, sometimes abruptly, and others in gentle hills to more than two thousand meters above sea level. (p. 5)

This province was leased to the Companhia de Moçambique (Figure 15), a private and prestigious company with sovereign rights delegated by the State.

Photographed by the author at the National Library of Portugal, 20 January 2023. Quotation C. C. 256 V. "Esboço do Território da Companhia de Moçambique" [cartographic material]

Figure 15: Draft of the territory of the Mozambique Company, November 1911

In order to contemplate the Mozambique Company's presence, it is pertinent to consider the notion that no one colonises innocently and that no one colonises with impunity either (Césaire, 1950/2022, p. 17). Stemming from the original company of the same name, by decree of December 21 1888, it was transformed into a sovereign company after the ultimatum of 1890, and its original charter was initially granted by decree of February 11, 1891. During its early phase, while still headquartered in Lisbon, the Mozambique Company was led by its first managing director, the historian Joaquim Pedro Oliveira Martins, described as "the most famous spokesman of the 70s generation" (Vasconcelos, 2022, p. 45). Oliveira Martins passed away in August 1894, yet his theoretical and ideological influence endured as one of the most consistently embraced by Portuguese social apparatus from the 1870s to the 1970s (Maurício, 2005). In the subsequent years, new decrees were issued to update the company's territorial expansion and administrative regulations (Companhia de Moçambique, 1929). The establishment of the Companhia de Moçambique followed several attempts to exploit abundant gold reserves, led by figures such as Army Officer Joaquim Carlos Paiva de Andrada. Additionally, it aimed to secure the effective occupation of Mozambican territory, as mandated by Portugal at the “Berlin Conference” in 1885 (Associação dos Amigos da Torre do Tombo, n.d.). In Portugal: A Companhia de Moçambique: Monografia Produzida Para a Exposição Portuguesa em Sevilha (Portugal: The Mozambique Company: Monograph Produced for the Portuguese Exhibition in Seville) in 1929, we can read:

when the Companhia de Moçambique was set up in 1891, mining fever spread throughout South Africa. In the lands of Manica and Sofala, more than anywhere else in Portuguese Africa, there was a firm inclination towards this form of exploration. (Companhia de Moçambique, 1929, p. 9)

Based in Beira, the Companhia de Moçambique exerted control over public administration and the postal service, issued currency through its own bank and exploited all resources in the region along with the local workforce, all under the guise of "exercising its civilising action" (Companhia de Moçambique, 1929, p. 8). This phrase, deeply entrenched in colonial discourse, is closely associated with a history marked by violence and dehumanisation (Kilomba, 2008/2019, p. 11). The Company of Mozambique undoubtedly played a role in shaping paradigms that perpetuated inequalities (Gilmore, 2023). It stood as an emblem of the numerous political institutions established by colonial powers, mirroring the structures of their metropolitan counterparts and bearing significant responsibilities in shaping the "roots of the present" (Sarr, 2016/2022). The Portuguese State issued Armando de Almeida's death registration, meeting the basic requirements for "submission to identification mechanisms". However, Almeida, as an individual, fulfilled a multitude of roles, both those automatically attributed to him and those he was able and allowed to undertake (Mbembe, 2020/2021, p. 103).

Thus far, our efforts to locate birth records, records of departure from Mozambique, or records of arrival in Portugal have been unsuccessful. It is even possible that such records do not exist, as cautioned by Catarina Simão19.

3. Final Considerations/Mastering Invisibility

Honouring and acknowledging the memory of Armando de Almeida entails recognising its significance while also recognising it as a history intertwined with "a violent reality". This violence, which has been "fundamental" in shaping European politics over the centuries (Kilomba, 2008/2019, p. 73), calls for a critical stance and nonconformity with a sentimental political assertion about the uninterrupted legacies of colonialism (Gilmore, 2023).

There is no evidence to suggest that Armando de Almeida belonged to a potential elite of the "metropolis". Rather, it seems that he would have been more akin to "a discriminated and subalternised body", possibly representing a type of "citizen of limbo [learning] to master invisibility" (Almeida, 2023, p. 86). This places him within the broader context of people of African descent who resided in the capital of the colonial empire, a phenomenon that has persisted over centuries. His capacity to engage in and participate in the ongoing system of sports activities during the tumultuous historical period of the First Republic, asserting themselves in public spaces, interacting with athletes from diverse social backgrounds, and climbing up the social ladder (Domingos, 2011), exemplified by the transition from Sport Club Cruz da Pedra to SCP, can always be viewed as a form of resistance, a cultural resistance with racial undertones, in a country that has yet to conduct a census on the ethnic and racial demographics of its population since 1864, the year of the inaugural census (Castelo, 2022).

Armando de Almeida's presence and role have been continually overlooked, distorted, and subalternised in the history and memory of Portuguese athletics.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the family of Arnaldo Garcez for the photo licensing and their invaluable kindness. This text was produced within the framework of the doctoral programme in Design at the Faculty of Fine Arts of the University of Porto, under the umbrella of the ID+ research unit, Research Institute for Design, Media and Culture. The research endeavour forms part of the project titled Stories of Ghosts: Contributions of visual anthropology to the retrieval and acknowledgment of narratives and documentation from the origins of Portuguese medium- and long-distance running, funded with an FCT, I.P. grant reference SFRH/PD/BD/150493/2019.

REFERENCES

Almeida, D. P. (2023). O que é ser uma escritora negra hoje, de acordo comigo. Companhia das Letras. [ Links ]

Andrade, S. (2010). Os recordes nacionais de atletismo e outras histórias. Prime Books. [ Links ]

Armando Almeida. (s.d.). In wikiSporting. Retirado a 9 de novembro de 2022, de https://www.wikisporting.com/index.php?title=Armando_Almeida [ Links ]

Associação dos Amigos da Torre do Tombo. (s.d.). Companhia de Moçambique/Grupo entreposto comercial de Moçambique. Retirado a 8 de novembro de 2022, de https://www.aatt.org/site/index.php?op=Nucleo&id=1640 [ Links ]

Braden, S. (1983) Committing photography. Pluto Press. [ Links ]

Cabecinhas, R. (2007). Preto e branco. A naturalização da discriminação racial. Campo das Letras. [ Links ]

Campany, D., & Wolukau-Wanambwa, S. (2022). Indeterminacy: Thoughts on time, the image, and race(ism). Mack. [ Links ]

O campeão da maratona Armando d’Almeida faleceu. (1918, 14 de agosto). Diário de Notícias, (18948), 3. [ Links ]

Cardão, M. (2020). Fado tropical. O luso-tropicalismo na cultura de massas (1960-1974). Livraria Tigre de Papel. [ Links ]

Cardina, M. (2023). O atrito da memória: Colonialismo, guerra e descolonização no Portugal contemporâneo. Tinta-da-China. [ Links ]

Cardoso, C. P. (2001). História do atletismo em Portugal. CTT. [ Links ]

Carneiro, J., Camanho, L., & Marques, S. L. (2022, 5-7 de dezembro). Armando de Almeida, o “negro invencível”, um campeão ausente na “história dos vencedores”. Lições de resistência e contra-memórias na cultura de corrida portuguesa [Apresentação de comunicação]. VIII Congresso Internacional sobre Culturas, Braga, Portugal. [ Links ]

Carreira, J. S. (1949). A corrida de maratona na história do atletismo português. In Separata do Boletim da Direcção Geral de Educação Física, Desportos e Saúde Escolar. DGEFDSE. [ Links ]

Casimiro, G. (2023). Estendais. Caminho. [ Links ]

Castelo, C. (2013, 5 de março). O luso-tropicalismo e o colonialismo tardio português. Buala. https://www.buala.org/pt/a-ler/o-luso-tropicalismo-e-o-colonialismo-portugues-tardio [ Links ]

Castelo, C. (2022, 5 de janeiro). Regressar a África ou ficar na metrópole: Agência negra e constrangimentos (1.ª metade do século XX). Buala. https://www.buala.org/pt/a-ler/regressar-a-africa-ou-ficar-na-metropole-agencia-negra-e-constrangimentos-coloniais-1-metade-d [ Links ]

Césaire, A. (2022). Discurso sobre o colonialismo, seguido de discurso sobre negritude (D. Paiva, Trad.). VS. Editor. (Trabalho original publicado em 1950) [ Links ]

Companhia de Moçambique. (1929). Portugal: A Companhia de Moçambique: Monografia para a exposição portuguesa em Sevilha. Imprensa Nacional de Lisboa. [ Links ]

Domingos, N. (2011). O desporto e o império português. In J. Neves & N. Domingos (Eds.), Uma história do desporto em Portugal. Volume II - Nação, Império e Globalização (pp. 51-107). QuidNovi. [ Links ]

Fernandes, A. M. (2010). Cem anos de maratona em Portugal. Xistarca. [ Links ]

Garção, M. (1913, 17 de março). Notas á margem. O Mundo, (4497), 1. [ Links ]

George, J. P. (2023). O império às costas. Retornados, racismo e póscolonialismo. Objectiva. [ Links ]

Gilmore, R. W. (2023). Abolition geography. Essays towards liberation. Verso. [ Links ]

Hall, S. (2003). Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices. SAGE. [ Links ]

Hasse, M. (1999). O divertimento do corpo - Corpo, lazer e desporto na transição do séc. XIX para o séc. XX, em Portugal. Editora Temática. [ Links ]

Jornal de Sport. (1914, 8 de agosto). (5), 2. [ Links ]

Kilomba, G. (2019). Memórias da plantação. Episódios de racismo quotidiano (N. Quintas, Trad.). Orfeu Negro. (Trabalho original publicado em 2008) [ Links ]

Maurício, C. (2005). A invenção de Oliveira Martins. Política, historiografia e identidade nacional no Portugal contemporâneo. Imprensa Nacional - Casa da Moeda. [ Links ]

Mbembe, A. (2021). Brutalismo (M. Lança, Trad.). Orfeu Negro. (Trabalho original publicado em 2020) [ Links ]

Moreira, C., & Rosado, C. (1913, 15 de junho). Depois de repetida a corrida da marathona é rijamente disputada e decorre com toda a regularidade. Tiro e Sport, (512). [ Links ]

Morte do corredor portuguez Armando d’Almeida. (1918, 15 de agosto). A Capital, (2868), 2. [ Links ]

O negro invencivel. (1913, 10 de maio). Os Sports Illustrados, (150), 4. [ Links ]

Os negros triunfam. (1913, 1 de abril). A Voz D’Africa, (15), 2. [ Links ]

Pasley, J. (2019, 9 de novembro). Inside Kenya’s Rift Valley, which produces the world's best marathon runners year after year. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/rift-valley-kenya-training-ground-world-best-runners-2019-11 [ Links ]

Pereira, A. M. (1998). Parceria A. M. Pereira - Crónica de uma dinastia livreira. Pandora. [ Links ]

Relvas, E. (2014). Eleições municipais em Lisboa na Primeira República (1910-1926) [Tese de doutoramento, Universidade Nova de Lisboa]. run. http://hdl.handle.net/10362/14493 [ Links ]

Roldão, C., Pereira, J. A., & Varela, P. (2023). Tribuna negra. Origens do movimento negro em Portugal (1911-1933). Tinta-da-China. [ Links ]

Rosas, F. (2010). Lisboa revolucionária, 1908 -1975. Tinta-da-China. [ Links ]

Sampaio, M. A. R. (1898). A Gorongóza. O seu presente e o seu futuro. Typographia Lusitana. [ Links ]

Sarr, F. (2022). Afrotopia (M. Lança, Trad.). Orfeu Negro. (Trabalho original publicado em 2016) [ Links ]

Semana desportiva do “Mundo”. (1913, 31 de março). Tiro e Sport, (507), 1. [ Links ]

A semana sportiva do “Mundo”. (1913, 17 de março). O Mundo, (4497), 1. [ Links ]

Semana sportiva do ‘Mundo’. (1913, 22 de março). Os Sports Illustrados, (143), 4. [ Links ]

Semana sportiva do ‘Mundo’. Depois das provas. (1913, 19 de março). O Mundo, (4499), 3. [ Links ]

Silva, D. F. (2022). Homo modernus - Para uma ideia global de raça (J. Oliveira & P. Daher, Trads.). Cobogó. (Trabalho original publicado em 2007) [ Links ]

Tavares, E. (2010). Retratos do povo. In J. Neves (Ed.), Como se faz um povo: Ensaios em história contemporânea de Portugal (pp. 401-414). Tinta-da-China. [ Links ]

Um grande atléta. (1913, 10 de maio). Os Sports Illustrados, (150), 4. [ Links ]

Uma tentativa coroada de exito. (1913, 17 de março). O Mundo, (4497), 1. [ Links ]

Varela, P., & Pereira, J. A. (2020). As origens do movimento negro em Portugal (1911-1933): Uma geração pan-africanista e antirracista. Revista de História, (179), a04119. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-9141.rh.2020.159242 [ Links ]

Vasconcelos, A. (2022). Memórias em tempo de amnésia (Vol. 1). Edições Afrontamento. [ Links ]

Zaccaro, N., & Carneiro, D. (2020, 9 de fevereiro). Luiz Antônio Simas: Bato tambor, logo existo. Revista Trip. https://revistatrip.uol.com.br/trip/luiz-antonio-simas-bato-tambor-logo-existo [ Links ]

2At the lower left corner of the reproduction, we can see the imprint of the Oficinas de Fotogravura Pires Marinho.

3Among the six occasions where this photograph appears, not always accurately depicting the corresponding event, this is the sole occurrence where the author's credits accompany it.

4Sociedade Promotora de Educação Physica Nacional — founded in 1909, is at the origin of the organization that came to be known as the Federação Portuguesa de Atletismo.

5In this case, the caption is odd due to the contradiction in the scant information it provides and the fact that the photograph had previously been disseminated with reference to another event that took place in March of the same year.

6In 1912, Armando Cortesão (1891-1977) represented Portugal at the Stockholm Olympic Games in the 800 m event, reaching the semi-finals. At 21, he was a student of Agronomy and an athlete for the Club Internacional de Football. Sequeira Andrade (2010) considers him to be "our first exponent of enduring speed, and not only that, as he rose to dominate the distances of 100m, 200m, 800m and 1000m, with victories and records" (p. 59).

7It is worth noting that this photograph of Armando Cortesão is replicated three times simultaneously on the same page as the photograph of Armando de Almeida (see Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5).

8An issue arises here: the "Sports Week" event by the newspaper O Mundo occurred in March, while the text published in June pertains to the marathon of the National Olympic Games held in May.

9The same photograph had previously been used to portray him as the "head of the medical service" during the "Sports Week" in O Mundo, Issue 4482, on March 2, 1913, Page 1.

10To some extent, this information also attempts to contribute to a possible answer to the question: "how do you make an invincible champion invisible?" researcher Felisberto Kiluanje posed after presenting the paper entitled Armando de Almeida, "o Negro Invencível", um Campeão Ausente na "História dos Vencedores". Lições de Resistência e Contra-Memórias na Cultura de Corrida Portuguesa (Armando de Almeida, "the Invincible Negro", an Absent Champion in the "History of the Winners". Lessons of Resistance and Counter-Memories in Portuguese Racing Culture), co-authored by Carneiro et al. (2022). The paper was presented at “GT1: Políticas, Contra-Memórias e Imaginários” (Politics, Counter-Memories and Imaginaries), moderated by Rosa Cabecinhas, during the "VIII Congresso Internacional Sobre Culturas, Culturas de Resistência", from December 5 to 7 2022.

11Hospital do Rêgo (1906-1929), called "Hospital for Infectious and ContagiousDiseases", was integrated into the Group of Civil Hospitals of Lisbon in 1913. In 1929, it was renamed "Hospital Curry Cabral" and is still in operation as part of the Central Lisbon Hospital Centre.

12It's plausible that António Maria Pereira (1895-1975) mentioned in the announcement could be the same person who became a publisher and later served as president of the National Guild of Writers and Booksellers from 1940 to 1957. Founder of the "Lisbon Book Fair" and councillor of the Lisbon City Council from 1946 to 1949. The grandson of António Maria Pereira (1824-1880), founder of the bookshop and publisher Parceria A. M. Pereira in 1824, son António Maria Pereira (1856-1880), politician and lawyer, founder of the law firm Pereira, Sáragga Leal, Oliveira Martins, Júdice & Associados in 1824. M. Pereira, in 1824, son António Maria Pereira (1856-1898) and father of António Maria Pereira, politician and lawyer, founder of the law firm Pereira, Sáragga Leal, Oliveira Martins, Júdice & Associados (Pereira, 1998).

13Serafim Martins (1888-1969), originally a donkey driver from Costa da Caparica, was several times winner of "professional pedestrian races". In 1914, the first time he was officially authorised to run the race, he became the national marathon champion.

14In Gisela Casimiro's (2023) book Estendais (Drying Racks), there's a moment where we read the following passage: "I can think of a pun between Yara's [Monteiro] novel and Joacine's [Katar Moreira] stuttering; instead of Essa dama bate bué (this lady beats a lot), it could be Essa dama gagueja bué (this lady stutters a lot)" (pp. 210-211). Considering the origin of the word "bué" (a lot) and the potential connection of Almeida to being a "son of Angola", we are also inclined to play with the paraphrase, suggesting: essa pessoa corre bué (that person runs a lot).

16Despite the extended length of the old Estrada da Palhavã, Number 22 places us in proximity to São Sebastião, near the present-day Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. The Public Security Police and Lisbon City Council have not verified the current address correspondence. If confirmed, Armando de Almeida would have been a neighbour near the Palhavã Stadium.

17The Great Rift Valley is a complex system of tectonic plate structures spanning from the Golan Heights, near Israel's border with Syria and Lebanon, to the heart of Mozambique, covering approximately 3,000 km. Over the past four decades, middle and long-distance races have been dominated by athletes from the East African part of the Rift Valley, particularly Kenya and Ethiopia. The town of Iten, situated around 2,400 m above sea level at one end of the Kenyan Rift Valley, is presently renowned as the world's most popular city for long-distance running training. It is internationally recognised as the "city of champions" (Pasley, 2019).

18We know very little about how the names of figures and places in the former Portuguese empire have been translated into Portuguese. For instance, Ngungunhane, the emperor of Gaza, is still commonly referred to as "Gungunhana" in Portuguese textbooks and media. Armindo Armando, a Mozambican researcher who has conducted empirical research in Gorongosa, although he doesn't have a specific written source, confirmed to us by email on February 12, 2024, that it’s a name translated from the Chiduma language.

Received: December 19, 2023; Revised: January 19, 2024; Accepted: January 19, 2024

texto en

texto en