Comunicação e Sociedade

ISSN 1645-2089 ISSN 2183-3575

30--2024

https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.45(2024).5376

Thematic Articles

Understanding the Role of IKEA Portugal’s Brand Values in Shaping the Purchase Decisions of Millennial Consumers

1 Centro de Estudos de Comunicação e Cultura, Faculdade de Ciências Humanas, Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Lisbon, Portugal

2 Faculdade de Ciências Humanas, Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Lisbon, Portugal

O presente artigo aborda a influência significativa da geração Y ou dos millennials no comportamento de compra e nas interações com a marca. O foco desta geração num mundo melhor e o facto de serem nativos digitais impulsionou mudanças no e-commerce e na forma como as empresas operam. Esta trata-se de uma geração preocupada com o planeta e com o futuro, que conseguiu forçar honestidade e transparência das empresas acerca dos seus produtos, processos e valores. Os millennials estão mais propensos a apoiar marcas que priorizam a responsabilidade social, a sustentabilidade e as práticas éticas. Os valores da marca ganharam destaque, moldando as perceções e o comportamento do consumidor. Esses valores representam as crenças e os princípios que a marca defende e têm um impacto significativo nas perceções dos consumidores sobre esta e o comportamento em relação a ela. O objetivo deste estudo é explorar como os valores da marca IKEA afetam as decisões de compra dos consumidores millennials portugueses. Foi utilizada uma metodologia quantitativa, com a aplicação de um inquérito por questionário, através do qual se obteve 402 respostas junto dos consumidores da marca IKEA. As principais conclusões indicam que os valores da IKEA Portugal impactam significativamente as decisões de compra dos consumidores millennials, especialmente as relacionadas com a relação qualidade-preço, sustentabilidade, responsabilidade social e apoio às comunidades.

Palavras-chave: cultura geracional; geração millennial; valores das marcas; comportamento do consumidor; decisão de compra

This article delves into the considerable influence of generation Y, or millennials, on purchase behaviour and brand interactions. Their focus on creating a better world, combined with their status as digital natives, has spurred changes in e-commerce and corporate practices. This generation prioritises environmental and social concerns, compelling companies to adopt honesty and transparency in their products, processes, and values. Millennials are inclined to support brands that demonstrate social responsibility, sustainability, and ethical practices. Consequently, brand values have become pivotal, shaping consumer perceptions and behaviours. These values reflect the beliefs and principles a brand embodies, significantly impacting consumer perceptions and behaviours toward it. The study aims to investigate how IKEA’s brand values influence the purchase decisions of Portuguese millennial consumers. A questionnaire survey was conducted, employing a quantitative methodology, yielding 402 responses from IKEA consumers. The primary findings reveal that IKEA Portugal’s values notably influence the purchase decisions of millennial consumers, particularly those related to value for money, sustainability, social responsibility, and community support.

Keywords: generational culture; millennial generation; brand values; consumer behaviour; purchase decision

1. Introduction

Brand values have an increasingly notable impact on consumers, shaping brand perceptions and selections. These values embody a brand’s fundamental beliefs and objectives, showcasing its core principles and daily pursuits. Present-day consumers value brands they perceive as trustworthy and relevant, often demonstrating a willingness to invest more in products that resonate with their beliefs and convictions and demonstrate environmental responsibility, ethical conduct, and social impact (Bond, 2021; Carr, 2021). In this landscape, organisations have shifted their focus to the consumer, recognising them as human beings with emotions, aspirations, and fears, prompting a paradigm shift and brand initiatives tailored to their needs (Kotler et al., 2011). However, the response to these needs varies among consumers and their respective generations, each harbouring distinct desires and requirements shaped by their unique experiences and socio-cultural environment.

Advocates of the environment and a more promising future, Generation Y or millennials, born between 1980 and 2000, have become increasingly discerning in their brand choices, favouring those that prove worthy of their loyalty and that work daily in favour of a greater good (Agrocluster, 2017; Costin, 2019; Deloitte, 2022; Lacerda & Borges, 2017; Merck, 2022a, 2022b).

IKEA, a renowned Swedish multinational in the furniture and home décor industry, embodies values that permeate its daily operations, from employee relations and decision-making processes to material sourcing and product design. Guided by its vision of “creating a better everyday life for most people” (IKEA, n.d.-c, para. 3), IKEA is dedicated to making a positive impact on both individuals and the planet through its ongoing efforts.

This article aims to understand whether a brand’s values - in this case, the values of IKEA Portugal - influence the purchase decisions of millennial consumers living in Portugal. It seeks to elucidate the significance of the IKEA Portugal brand’s values for millennial consumers.

2. Millennials and Their Purchase Decision Process

Consumers typically make brand choices as they navigate internal conflicts aimed at fulfilling their needs in the best possible way, whether they be physiological or selfactualisation needs (Maslow, 1943).

Cultural brand strategy involves applying a strategy that considers the cultural, societal, and political context in which a brand operates. This approach is crucial for developing new businesses and resurrecting moribund ones. Cultural branding aims to identify cultural opportunities and develop strategies to leverage them effectively (Holt, 2012).

In today’s market, leading brands are characterised by their distinctive culture, which is the outcome of a combination of strategies known as the “cultural branding model”. This model emerges from the brand’s capacity to comprehend the transformations occurring across society as a whole, irrespective of the market (Holt & Cameron, 2010).

Distinctive and iconic brands aspire to exceed expectations and soar above, aiming to inspire action and critical reflection in their consumers. They “provide extraordinary identity value because they address the collective anxieties and desires of a nation” (Holt, 2004, p. 6), and they “function like cultural activists, encouraging people to think differently about themselves ( ... ) [they are] prescient, addressing the leading edges of cultural change” (p. 9). Nevertheless, consumers follow their own process when it comes to choosing these distinctive brands and their products from among the numerous options available on the market.

Consumer behaviour “reflects the totality of consumer’s decisions with respect to the acquisition, consumption and disposition of goods, services, activities, experiences, people and ideas” (Hoyer et al., 2012, p. 3). It extends far beyond the tangible purchase of products and is often influenced by the choices of other individuals. Understanding these behaviours and their origins enables brands, through marketing, to address consumer needs, prioritise them, and afford them the relevance they deserve (Kotler et al., 2011).

Indeed, multiple factors impact an individual’s acquisition of products and services, encompassing their personality, lifestyle, and the symbolic connotations attached to brands and products, which often reflect the social status of the consumer (Baudrillard, 1998; Kotler et al., 2020; Maslow, 1943). According to Kotler et al. (2020), consumer behaviour is influenced by four primary factors, which are interpreted in descending order from a broader perspective to a more specific one: external factors (cultural and social) and internal factors (personal and psychological).

This provides a detailed explanation of each of the factors discussed: (a) cultural factors - the consumer’s culture, subculture, and social class are significant influencers of consumer behaviour (Kotler & Keller, 2012), shaping values, perceptions, ambitions, norms, behaviours, and actions inherent to the society of origin (Baudrillard, 1998); (b) social factors - social groups of influence such as family, friends, reference groups, and social status within the hierarchy impacts consumer behaviour (Hoyer et al., 2012), prompting individuals to favour themes, brands, and other categories recommended by their groups and shaping their consumption patterns; (c) personal factors - specific characteristics including age, life stage, occupation, economic status, lifestyle, personality, and self-image play a role in shaping behaviour; (d) psychological factors - motivation, beliefs, and attitudes are key aspects influencing consumer behaviour, with Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of needs being one of the most widely used theories to understand human motivation. This theory is organised into five hierarchical categories, each representing different levels of importance to the individual, starting from the most basic and progressing towards higher levels of fulfilment: (a) physiological needs; (b) safety needs; (c) social needs; (d) esteem needs; and (e) self-actualisation needs.

The purchase decision-making process starts long before the actual purchase and continues long after (Kotler & Keller, 2012; Kotler et al., 2020; Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). Over the years, consumers have gained increasing relevance in the market. In marketing 1.0, the focus was primarily on the industry, with products and sales as its central elements. However, over time, consumers have become the focal point of organisations (Kotler et al., 2011, 2017).

Traditional methodologies (e.g., Engel et al., 1968, 1986; Howard & Sheth, 1969; Kotler et al., 2020; Nicosia, 1966) have lost their prominence as they struggled to adapt to the evolving societal changes that have fundamentally transformed the entire purchase decision process, including factors like technology integration and impulse buying. These conventional models have relative utility in assessing consumer behaviour in today’s hyper-consumerist society, characterised by excessive consumption driven by various factors, including social pressures to acquire goods as a means of shaping individual identity (Baudrillard, 1998; Cyr, 2018). Nonetheless, these models serve as foundational frameworks for understanding the historical context of the consumer purchase decision process, providing insights into their evolution over time. Contemporary approaches increasingly focus on comprehensively understanding consumer experiences and decisions, placing them at the forefront of research efforts and embracing methodologies such as consumer decision journey mapping (Kotler et al., 2017; Santos & Gonçalves, 2021).

According to Kotler et al. (2020), the purchase decision process consists of five distinct phases, each aimed at fulfilling an individual’s need: (a) need recognition - the consumer recognises a problem or need. The need can be triggered by internal stimuli, like physiological needs such as hunger or thirst, or external stimuli such as an advertisement or a discussion with a friend; (b) information search - if the consumer’s drive is strong and a satisfying product is near at hand, the consumer is likely to buy it then. If not, he or she may undertake an information search related to the need and identify the best available alternatives. This phase allows consumers to form an informed opinion about their decision; (c) evaluation of alternatives - in this phase, consumers process the information gathered during the search stage to choose a product or service from among the available brands. This is a complex process that involves various evaluation processes, and it depends on the individual consumer and the specific buying situation; (d) buying decision - the decision phase is the culmination of the previous steps, after forming their intention to purchase and ranking the brands; and (e) post-purchase behaviour - the purchase decision process does not end with the purchase itself. After buying the product or service, consumers evaluate their satisfaction or dissatisfaction based on their expectations and the perceived performance of the product. This phase is crucial as it directly influences future buying behaviour and brand loyalty (Kotler et al., 2020).

The truth is that each generation is different, moulded by its unique socio-cultural context and life experiences. Indeed, brands are aware of these distinctions, prompting them to cater uniquely to each generation. They endeavour to tailor experiences and business strategies to meet the demands and preferences of each generation, given their varying tastes and attitudes toward products and services available in the market. According to Wellner (2003), the emergence of timeless, intergenerational brands will be one of the main marketing trends by 2025. Generational marketing stands out by addressing the distinctive requirements of individuals within a specific generational group who share the same era and experience particular historical milestones.

In an era defined by technology and progress, human adaptation prevails. The “digital generation” or “digital natives” (Gurău, 2012; Howe & Strauss, 2000; Twenge, 2010) epitomises a generation of young individuals born between the 1980s and the 2000s who have learned from an environment conducive to complete digital integration, “influencing their personality, beliefs, behaviours and attitudes” (Calvo-Porral et al., 2018, p. 231). Descendants of the baby boomers and generation X, millennials have grown up in a globalised and technologically driven world. While a significant part of their daily activities revolves around digital interaction, that does not mean that this is their focus and priority. This generation wants to collect life stories rather than wealth and material possessions, leading them to consume fewer products compared to older generations (Kotler et al., 2021). Portuguese millennials, in particular, aspire to a more sustainable and inclusive future, advocating for action from organisations in support of equality, diversity, and inclusion (Merck, 2022a).

Millennials’ consumption habits are influenced by a multitude of factors, including digital progress, growing environmental awareness, and socio-economic changes. Their decision-making processes are also influenced by factors such as the brand they are considering, the feedback from their peers, and the environmental and social responsibility demonstrated by brands. Costin (2019) argues in Forbes that millennials base their purchase decisions on several key values, including (a) social responsibility, (b) environmental concern, (c) authenticity, (d) local sourcing, (e) ethical production, and (f) giving back to society. The author’s research indicates that 75% of millennials prioritise companies that give back to society over those solely focused on profitability. This generation is recognised for its commitment to sustainability and social action (Deloitte, 2022; Merck, 2022a), thus placing a high value on sustainable consumption and companies that prioritise environmental and social responsibility (Agrocluster, 2017; Costin, 2019; Lacerda & Borges, 2017).

According to Woo (2018), millennials approach decision-making in various categories with the following insights: (a) millennials want their purchases to make them feel good: they value money and products that can satisfy their rational and emotional needs together; (b) millennials value experiences: they rather pay for experiences than material things and are willing to pay extra for this; (c) sharing: millennials like to share their opinions, positive or negative, about a product on their social networks, promoting their forum for debate and opinions; (d) millennials buy products and services promiscuously: they exhibit low brand loyalty and are more inclined to try new and innovative brands rather than stick to familiar ones. Brands should focus on understanding their needs, both rational and emotional, to capture their attention and encourage repeat purchases; (e) millennials rely on peer recommendations: more than a third of millennials prefer to wait for trusted peers’ feedback before making purchase decisions. While open to new experiences, millennials actively avoid brand communications and place more trust in word-of-mouth about the brand’s products and services (Costin, 2019); and (f) millennials seek relevance: customisation and relevance resonate with this group, which values brands that tailor their advertising and social media content to their interests and preferences, fostering a stronger connection with the audience.

3. The Object of Study: IKEA Portugal

With Swedish origins, IKEA, founded by Ingvar Kamprad in 1943, initially sold smaller items (IKEA, n.d.-a), but in 1948, it invested in a new product category: furniture, with Ingvar himself having the opportunity to design his own furniture (IKEA, n.d.-a; Kamprad & Torekull, 2006/2010). After opening its first showroom and shop in Älmhult under the name Möbel-IKÉA in 1958 (IKEA, n.d.-a; Kamprad & Torekull, 2006/2010), expansion was inevitable. By 1970, IKEA had already expanded into countries like Denmark and Norway, and in subsequent years, it continued its global expansion into places like Australia and Singapore. In 1980, big decisions were made. Ingvar sought to give IKEA an “eternal life” by separating the ownership of the retail operation from the IKEA concept and the IKEA brand. This separation led to the establishment of independent business groups operating under a franchise system (IKEA, n.d.-a).

The first IKEA Portugal shop opened in 2004 in Alfragide. Presently, IKEA Portugal has five outlets nationwide - Alfragide, Loures, Loulé, Braga, and Matosinhos - and operates several planning studios and an online sales platform (IKEA, n.d.-b).

Guided by its vision “to create a better everyday life for the many people” (IKEA, n.d.-c, para. 3), the brand strives “to offer a wide range of well-designed, functional home furnishing products at prices so low that as many people as possible will be able to afford them” (para. 6). IKEA’s values reflect what they consider to be important and guide their work, decisions and interactions. IKEA is driven by its eight “forever parts” (IKEA, n.d.-c, para. 12), also called “values”: (a) “different with a meaning” - curiosity, enthusiasm, and a desire to drive positive changes in the industry and the world sets it apart from other companies, challenging existing solutions and striving to take risks and learn from the past, always with an eye on a more accessible and sustainable future; (b) “costconsciousness” - every day, IKEA seeks to eliminate unnecessary costs and implement solutions to make its products accessible at low prices to most people, challenging itself and others to make more from less without compromising on quality, functionality, sustainability and design; (c) “simplicity” - the search for simplicity both regarding products and business bureaucracies, focusing on the most simple, straightforward and down-to-earth approach, making all processes more efficient and natural; (d) “caring for people and planet” - directly related to the brand’s sustainability strategy reflecting its ongoing commitment to making a significant and lasting impact on people and the planet, offering more sustainably sourced and manufactured products and sharing green information and content to help people live a more sustainable life at home and continuously supporting human rights, the community and children. By taking on this responsibility, IKEA has the chance to help create a better life for most people, becoming a force for positive change, locally and globally; (e) “renew and improve” - reflects IKEA’s dedication to constantly enhancing its operations and addressing challenges encountered on a daily basis, always considering the best for most people. According to IKEA, there is no such thing as “impossible”, and they “go the extra mile” to constantly find solutions to move forward; (f) “togetherness” - “tillsammans” in Swedish, is at the very heart of IKEA culture. It emphasises fostering trust, encouragement, and genuine camaraderie among team members, promoting collaboration and collective growth; (g) “lead by example” - IKEA gives people’s values as much weight as their competence and experience, advocating for the organisation’s values and people who “walk the talk”. “Lead by example” starts with being aware of one’s own behaviour and the consequences of one’s actions, big or small; (h) “give and take responsibility” - IKEA promotes trust and fosters autonomy among its employees, enabling them to evolve and grow within the organisation by embracing each task and challenge. As Ingvar says, “IKEA is not the work of one person alone. It is the result of many minds and many souls working together through many years of joy and hard work” (IKEA, n.d.-c, para. 8).

4. Methodology

The methodological strategy applied is based on a case study, which examines the influence of a brand’s values - in this specific case, IKEA Portugal - on the purchase decision process of Portuguese millennial consumers. It is worth noting that these values are shared across the broader IKEA brand.

This study employs a quantitative methodology involving the distribution of questionnaire surveys to millennial consumers of IKEA Portugal.

The principal objective of this study is to address the research question: “does the perception of IKEA’s brand values influence the purchase decision process among its millennial customers in Portugal?”. The questionnaire survey incorporates variables corresponding to IKEA Portugal’s eight values. This approach enables the examination of the relevance and correlation between IKEA Portugal’s values and the purchase decisions of its millennial consumers regarding furniture and decoration products.

The questionnaire was disseminated online through personal social networks such as Facebook, WhatsApp, and Instagram, as the company was unable to use IKEA’s social media platforms to reach Portuguese millennial consumers. It was conducted through the Google Forms platform. In order to ensure the responses met the sample parameters, two important exclusion factors were established: (a) responses from individuals who were not regular or occasional consumers of the IKEA brand were disregarded, as the study’s focus was to assess the influence of the brand’s values on the purchase decision process; and (b) responses from individuals outside the millennial generation were excluded. The sampling method employed was non-probabilistic convenience sampling, comprising individuals who were available and willing to participate in the questionnaire.

According to Huot (1999/2002), for a universe equal to or greater than 100,000 individuals where N>100,000, as in the case of IKEA (2021), a minimum sample size of 384 is required since n=384. In this way, the questionnaire survey was made available for six weeks (from April 5, 2023, to May 12, 2023). Considering that in the first four weeks, it had not been possible to obtain a significant sample, the decision was made to extend the survey for an additional two weeks. This extension proved beneficial, as it was possible to get a total sample of 476 IKEA Portugal consumers.

Hence, the online questionnaire was accessible for 42 days to assess the perceptions and opinions of Portuguese millennial consumers (aged 22 to 44 who consume IKEA Portugal products) during the study’s timeframe, spanning from April 5, 2023, to May 12, 2023, as previously indicated.

The questionnaire comprised a total of 12 questions, with Question 1 intended to understand the respondents’ perception of IKEA’s values. Question 2 was drafted to inquire about each distinct IKEA value, albeit indirectly, to ensure subtlety and provide an opportunity to evaluate the values individually based on the sample’s perceptions. Questions 3 to 12 were formulated to enable the comparison of the association of values with the brand and to assess the impact that Portuguese millennial consumers attribute to each of these values on their decision to purchase furniture and decoration products and services.

The total sample collected was comprised of 476 participants who identified as consumers of IKEA Portugal. However, only 402 responses met the criteria outlined for this study, excluding those from non-regular or occasional consumers of the IKEA brand and individuals outside the millennial generation. Data analysis was conducted using the Excel program.

The methodological framework for assessing values, drawing on the model proposed by Sheth et al. (1991), was employed to address the research question, aiming to examine the perceptions of millennial consumers of IKEA Portugal.

Therefore, the model proposed by Sheth et al. (1991), which has been applied in numerous studies (e.g., Gonçalves et al., 2016; Zainuddin et al., 2008), does not focus on the process itself but rather on the factors or aspects that influence the purchase behaviour concerning products and/or services. This model was deemed the most suitable for addressing the research question because it delineates five fundamental consumer values that impact the purchase decision process: (a) “functional value”, which reflects the physical, useful, or practical attributes of a product, thus emphasising functionality and associated product attributes such as durability, affordability, safety, and reliability; (b) “social value”, representing a general aggregation, positive or negative, with demographic, socio-economic, cultural, or ethnic groups; (c) “emotional value”, which emerges from an alternative and leads to an affective or emotional state in the consumer, such as feelings or memories; (d) “epistemic value”, which stems from new stimuli or misconceptions when presented with an alternative, which captures attention, sparks curiosity, and offers novelty, enabling new experiences and routines for the consumer. It is relevant to their personality, influencing their receptiveness to novel information; and finally, the (e) “conditional value”, which considers the situational context and occurs based on the specific conditions or circumstances of the purchase decision.

This model focuses on the factors influencing purchase behaviour, using its variables (particularly “emotional value”, “functional value”, and “social value”) to relate to the essential aspects of millennials’ purchase decision process (Agrocluster, 2017; Costin, 2019; Woo, 2018) and the pillars outlined in the model by Enquist et al. (2007).

Thus, the goal was to gauge respondents’ awareness of IKEA’s values, indirectly defining and informing them about all the values and initiatives undertaken by the brand in alignment with its vision, to ascertain the level of importance attributed by consumers to each individual value of the brand.

5. Presentation of Study Data

Regarding the presentation of the data, Figure 1 illustrates the responses to Question 1 - “what values do you associate with IKEA?” - respondents were asked which values they associated with IKEA Portugal. The options provided included both the eight values of IKEA and those of competing brands. This setup aimed to assess participants’ ability to differentiate between the values of the brand under study and those of its competitors. Therefore, alongside IKEA’s specific values, general values like “innovation” and “transparency”, as well as competitor values such as “authenticity”, “interdependence”, “democratic”, “passionate about design”, and “specialists in decoration and smiles”, were included.

Figure 1 Outcomes of respondents’ replies to Question 1 concerning the values linked with IKEA Portugal

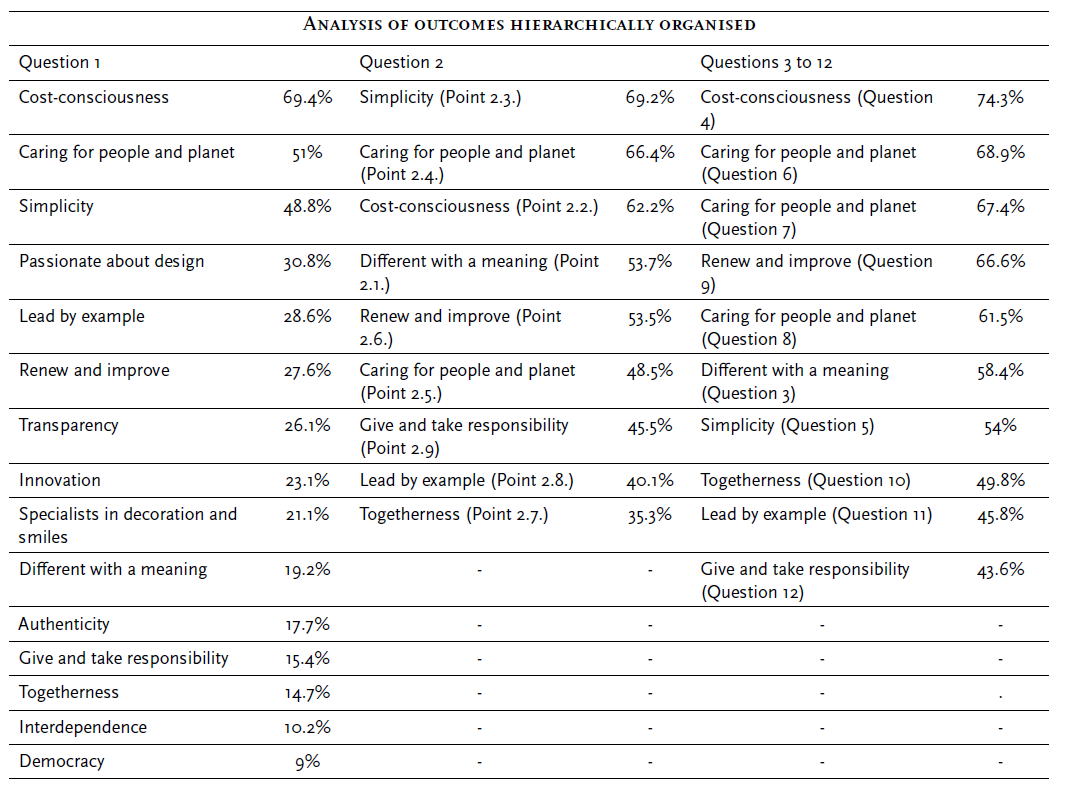

As illustrated in Figure 1, the top three values selected by respondents are inherently associated with the IKEA brand. This indicates that Portuguese millennial consumers perceive the brand’s commitment to “cost-consciousness”, “caring for people and planet”, and “simplicity”. Nevertheless, values like “different with a meaning”, “give and take responsibility”, and “togetherness” are among those least linked to the brand by the surveyed individuals. This phenomenon may be attributed to the fact that these latter two values are more accentuated within IKEA as an employer rather than in external communication.

In Question 2 (Table 1), participants were presented with nine statements and asked to rate their agreement using a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5. Here, 1 represented “strongly disagree”, 2 “disagree”, 3 “neither agree nor disagree”, 4 “agree”, and 5 represented “strongly agree”. The intention was to indirectly inquire about each of IKEA’s values, allowing for individual assessment based on the respondents’ perceptions. In this question, nine statements were provided corresponding to each IKEA value, except for “caring for people and planet”, which had two statements associated with it, reflecting the brand’s exceptional dedication to this value.

Table 1 Correlation between questions and IKEA Portugal’s values, along with the corresponding outcomes for each

For the value “different with a meaning”, the findings from Question 2, specifically Point 2.1. - “IKEA Portugal challenges the status quo” - indicate that 53.7% (216 respondents) agreed or strongly agreed with this statement.

Analysing the data related to the value “cost-consciousness”, it is evident that this value is the most associated with IKEA Portugal by its specific name, demonstrating that it is directly associated with the brand among the majority of the respondents. Specifically, Point 2.2. reveals that 62.2% (250 respondents) agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “IKEA Portugal’s products and services have low prices”, underscoring the brand’s recognition for its consistent efforts to offer affordable furniture and decoration items accessible to a wide range of consumers.

Regarding the value “simplicity”, it is apparent that it is associated with IKEA Portugal, ranking as the third most associated value with the brand through its direct name. Point 2.3. - “IKEA Portugal is known for its simplicity in its products and services and in the company itself” - further illustrates this association, with 69.2% of respondents (278) agreeing or strongly agreeing with the statement.

The value “caring for people and planet” emerged as the second most associated value with IKEA Portugal, indicating that respondents strongly connect this value with the brand. This association likely stems from IKEA’s consistent commitment to sustainability initiatives and its efforts encouragement to help the planet. Point 2.4. - “IKEA Portugal is a sustainable brand” - received significant agreement from respondents, with only 14.2% (57) indicating they disagreed or strongly disagreed, while 66.4% (267) expressed they agreed or strongly agreed. Only 19.4% (78) of the sample neither agreed nor disagreed with this sentence. Similarly, Point 2.5. - “IKEA Portugal supports vulnerable communities and groups” - garnered agreement from 48.5% (195) of respondents, while 27.9% (112) were indifferent and a total of 22.6% (95) disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement. Hence, as can be seen below, there is some lack of awareness regarding IKEA Portugal’s initiatives to support vulnerable groups and communities. There is a need to invest more in publicising these efforts, considering that nearly 70% of respondents view this as a pivotal factor in their decision-making process when purchasing furniture and decoration products and services.

The value “renew and improve” ranked fifth most associated with the IKEA Portugal brand. In addition, in Point 2.6. - “IKEA Portugal is constantly improving and finding better ways of doing things”, 53.5% (215) of the sample agreed or strongly agreed with the sentence, and 27.4% (110) neither agreed nor disagreed.

Upon analysis of the findings concerning the value of “togetherness”, it became evident that this was the least associated value with IKEA Portugal in Question 1. There is a variation compared to the previous questions, presented in Point 2.7., where 45.8% (184) of the sample neither agreed nor disagreed with the question, 29.1% (117) agreed, 10.9% (44) disagreed, 8% (32) strongly disagreed, and 6.2% (25) strongly agreed. This shift may stem from the brand’s more internal exploration of value rather than its external communication of it, thus making it less associated with it by the public.

Regarding the value “lead by example”, it ranked as the fourth associated value with IKEA Portugal, making it the fifth most hierarchically associated value when competitor values are also considered. When we also analysed Question 2, Point 2.8. - “IKEA Portugal has employees who are consistent in their words and attitudes and who lead by example” - 40.1% (161) of the sample agreed or strongly agreed with this statement. However, it is worth noting that this constituted only a 2.3% (9) difference, as 37.8% (152) neither agreed nor disagreed.

The value “give and take responsibility” was the seventh brand value associated with IKEA Portugal, ranking as the second least associated brand value. Compared to previous points, a variation was observed: 40.5% (163) of the sample agreed, 37.6% (151) neither agreed nor disagreed, 8.7% (35) disagreed, 8.2% (33) strongly disagreed, and 5% (20) strongly agreed with the statement.

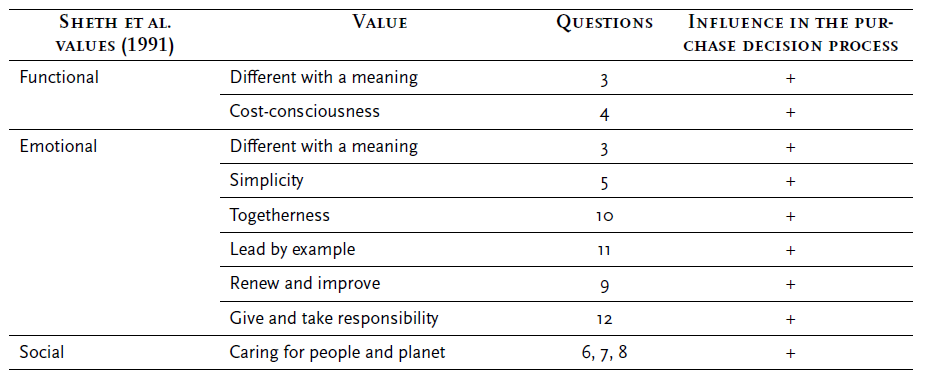

To compare the collected data and gather more nuanced insights, we used the values outlined by Sheth et al. (1991), specifically their “functional”, “emotional”, and “social values” (Table 2). Additionally, we considered the factors influencing the purchase decision process, as highlighted in previous analyses of essential aspects of millennials’ purchase decision process (Agrocluster, 2017; Costin, 2019; Lacerda & Borges, 2017; Woo, 2018), along with the pillars outlined in Enquist et al.’s (2007) model corresponding to each brand value. This approach enabled a deeper understanding of the significance of brand values in the purchase decision process of Portuguese millennial consumers.

Table 2 Correlation between the factors influencing millennials’ purchase decision process and IKEA Portugal’s values, based on theSheth et al. model (1991)

Each of Questions 3 to 12 matched an IKEA value to enable the comparison of the association of values with the brand and to assess the impact that Portuguese millennial consumers attribute to each of these values on their decision to purchase furniture and decoration products and services. Respondents were asked to rate the importance of the following statements for their purchase decisions using a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5. On this scale, 1 corresponds to “not at all important”, 2 to “not very important”, 3 to “indifferent”, 4 to “important”, and 5 to “very important” (Table 3).

Table 3 Outcomes of the importance of IKEA Portugal’s values in the purchase decision process of Portuguese millennial consumers

Table 4 was created to simplify the analysis of the outcomes presented above and address the research question. It displays the positive responses (sum of answers 4 and 5 on the Likert scale) to all the questions posed, organised hierarchically according to their corresponding values.

Table 4 Analysis of the outcomes obtained from Questions 1 to 12, organised hierarchically, according to the positive responses obtained in each question

Therefore, Table 5 presents the correlation between the values of Sheth et al. (1991) and IKEA’s values and the influence they have on the purchase decision process.

Table 5 Correlation between IKEA Portugal’s values and the fundamentals of theSheth et al. (1991) model and their influence on the purchase decision process

The analysis of the outcomes presented in Table 5 will be structured based on the presentation of the “functional”, “emotional”, and “social” values (Sheth et al., 1991) rather than following the sequence of Questions 3 to 12 in the questionnaire. This approach aims to provide a clearer understanding of the relationship between these three values and the outcomes obtained regarding IKEA’s values and their impact on the purchase decision process.

Regarding the “functional value”, two values attributed to the IKEA Portugal brand were identified: “different with a meaning” and “cost-consciousness”. These values align with Questions 3 and 4, respectively, which seek to evaluate factors influencing the purchase decision process related to functional aspects such as product function, price, quality, range/form, and customisation.

According to Question 3, “is IKEA’s ongoing effort to explore new ways of surprising and inspiring positive change in the world a determining factor in [my] decision to purchase furniture and decoration items?”, 58.4% of respondents deemed it important or very important. This indirectly suggests the relevance of the “different with a meaning” value to their purchasing decisions, indicating its significance to millennial consumers (refer to Table 4). Thus, concerning the “different with a meaning” value, it appears to align with the variables associated with the “functional value” outlined by Sheth et al. (1991), demonstrating its influence on the purchase decision process. Notably, although IKEA’s name might not be directly associated with this value (as evident in Figure 1), its actions are recognised and valued by its audience (as shown in Table 1), making it the fourth most impactful value on the purchase decisions of Portuguese millennial consumers, as per Question 2.

In addressing the value of “cost-consciousness” in Question 4 - “does IKEA’s commitment to offering its products at affordable prices significantly influence my decision to purchase furniture and decoration items?” - a notably positive response was observed. The vast majority of the sample, accounting for 74.3%, deemed this value important or very important in their decision-making process when purchasing furniture and decoration products. This underscores the significance of value for money to this generation, with affordability being a crucial factor. This value aligns with the “price” variable associated with the “functional value” paradigm, emerging as the primary determinant in the decision to purchase furniture and decoration products, as indicated by the data in Table 4.

Thus, it is possible to infer that within the “functional value”, the IKEA value with the greatest impact on the purchase decision process for furniture and decoration products and services is “cost-consciousness”. This finding corroborates the insights gleaned from prior literature reviews (Costin, 2019; Deloitte, 2022; Merck, 2022a), which suggest that millennials prioritise value for money and are inclined towards brands they trust and perceive as offering quality, irrespective of price point. Consequently, it becomes evident that in relation to “functional value”, with which these two IKEA Portugal values are associated, the balance was positive, and their influence on the purchasing decision process of Portuguese millennial consumers is substantial, as illustrated in Table 5.

Six distinct IKEA Portugal values were included in the umbrella of “emotional value”, namely: “different with a meaning”, “simplicity”, “togetherness”, “lead by example”, “renew and improve”, and “give and take responsibility”. These values correspond to Questions 3, 5, 10, 11, 9, and 12, respectively. The objective of these questions is to evaluate the factors that influence the purchase decision process, which fall within the “emotional value” variables (innovation, honesty, consistency, promoting difference and originality, and striving for continuous improvement). Question 3 was analysed earlier.

The value of “simplicity” was perceived as a decisive factor by 54% of the respondents in their decision-making process for purchasing furniture and decoration, as indicated in Question 5: “does IKEA’s preference for simplicity, whether in its communication or its approach to bureaucracy, play a significant role in my decision to purchase furniture and decoration items?”. However, it is noteworthy that 32.3% of the sample expressed indifference towards “simplicity” in this question (Table 3), ranking it fifth in terms of values that significantly influence the consumer’s purchase decision (see Table 4). This suggests that “simplicity” is not a top priority value for Portuguese millennial consumers when making purchase decisions.

Therefore, the value of “simplicity” demonstrated its relevance in addressing the variables associated with it (honesty and consistency) within the framework of “emotional value” outlined by Sheth et al. (1991).

Question 10, which pertains to the value of “togetherness” - “IKEA’s preference for simplicity, whether in its communication or its approach to bureaucracy, play a significant role in my decision to purchase furniture and decoration items” - revealed that 49.8% of the sample considers this value important or very important and perceives it as a decisive factor in their purchase decision for furniture and decoration (Table 3). It is possible to conclude that “togetherness” ranks as the sixth determining factor in the purchase decision process (refer to Table 4), notably in Question 2, Item 2.7. - “IKEA Portugal has united employees” - 45.8% of respondents expressed indifference, indicating a lack of awareness regarding the actual unity among IKEA Portugal’s employees or the brand’s adherence to this value.

Regarding the value “lead by example”, 45.8% of the sample perceives it as a determining factor in their decision to purchase furniture and decoration items, 29.1% expressed indifference, and 25.1% admitted it held little or no importance in their purchase decision (refer to Table 3). Consequently, it becomes evident that compared to other values, “lead by example” is not as significant to the Portuguese millennial consumer. Therefore, it ranks as the second-to-last value to be considered when making a purchase decision (see Table 4).

The value “renew and improve” was deemed a significant factor in the decisionmaking process for purchasing furniture and decoration items, with 66.6% of the sample considering it important or very important (refer to Table 3). Consequently, it can be established that this value ranks as the third most influential factor in the purchase decisions of millennial consumers (see Table 4).

The value “give and take responsibility”, addressed in Question 12 - “the fact that IKEA gives its employees autonomy from the start of their career and invests in them so that they grow influence my decision to purchase furniture and decoration items” - garnered a significant number of indifferent responses, accounting for 36.8% or 148 individuals. However, when considering the answers categorised as important and very important, totalling 43.6% or 175 individuals, it becomes evident that this value indeed influences the decision-making process of Portuguese millennial consumers when purchasing furniture and decoration items (refer to Table 3). Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that the difference in responses between importance levels was relatively small (27), indicating a notable level of indifference, particularly towards values that are more internally focused at IKEA Portugal. Therefore, while it holds importance for the majority, it ranks as the least influential value to be considered (see Table 4).

Regarding the “emotional value”, encompassing six associated values - “different with a meaning” (Question 3), “simplicity” (Question 5), “togetherness” (Question 10), “lead by example” (Question 11), “renew and improve” (Question 9), “give and take responsibility” (Question 12) - there was a positive balance, indicating an influence on the consumer’s purchase decision process.

On the other hand, the factors aligned with the “social value” of Sheth et al. (1991) - sustainability, social responsibility, ethical production, and support to communities - were addressed in Questions 6, 7, and 8, regarding the value “caring for people and planet” (refer to Table 1; Costin, 2019), aiming to evaluate the values of the IKEA brand.

Analysing the results of Question 6 - “IKEA’s commitment to environmental sustainability, such as selecting sustainable materials and striving to provide zero-emission delivery services, significantly influence my decision to purchase furniture and decoration items” - which emphasises sustainability and ethical production, it was considered important and very important by 68.9% of the sample, accounting for 277 respondents. It is also noteworthy that only 13.9% of respondents (equivalent to 56 individuals) indicated that this factor was not very or not at all important in their purchase decision (refer to Table 3).

Question 7 - “IKEA’s commitment to supporting vulnerable communities and groups, such as victims of domestic violence and refugees, influence my decision to purchase furniture and decoration items” - emphasises social responsibility and support to communities. It was shown to be a determining factor in the decision to purchase furniture and decoration items, as it had the highest number of “very important” responses of the questions associated with “social value”. Of the sample, 67.4% of respondents stated that it was important and very important for their purchase decision, indicating its relevance for millennial consumers.

Question 8 - “does IKEA’s commitment to promoting equality, diversity, and inclusion, both within and outside the company, play a significant role in my decision to purchase furniture and decoration items?” - it has proved to be a determining factor in the decision to purchase furniture and decoration items for Portuguese millennial consumers, since 61.5% of the sample, or 247 respondents, consider this aspect to be important or very important, indicating its relevance to consumers.

As discussed above, the factors that fall under Sheth et al.’s (1991) “social value”

- sustainability, social responsibility, ethical production, and support to communities - align with the value of “caring for people and planet” and its corresponding questions - 6, 7 and 8 - which it was concluded to be a determining value for the furniture and decoration purchase decision process (see Table 4). Thus, by associating this IKEA value with “social value”, it can be inferred that the overall balance of “social value” is positive (refer to Table 5).

6. Final Considerations

This study endeavoured to explore how brand values influence the purchase decisions of millennials. Through a comprehensive literature review, coupled with the collection and thorough analysis of primary data via a questionnaire survey, the research aimed to address the fundamental query: “does the perception of IKEA’s brand values influence the purchase decision process among its millennial customers in Portugal?”.

The millennial generation is better educated, idealistic, open-minded, culturally diverse, ambitious, and often impatient. It is inclined to break down barriers, both professionally and in terms of their own mental health and the way they view life. Millennials are notably dedicated to sustainability, social responsibility, and inclusivity, advocating for brands to align with their values and contribute to a better future (Agrocluster, 2017; Costin, 2019; Deloitte, 2022; Lacerda & Borges, 2017; Merck, 2022a, 2022b; Woo, 2018).

In response, brands must understand the priorities and motivations of millennials in their purchase decisions. Companies are increasingly differentiating themselves through their values, aiming not only for profitability but also to address complex social and environmental challenges (Kotler et al., 2021).

IKEA, guided by its vision of “creating a better everyday life for most people” (IKEA, n.d.-c, para. 3), remains steadfast in its commitment to eight core values- “cost-consciousness”, “simplicity”, “togetherness”, “caring for people and planet”, “renew and improve”, “give and take responsibility”, “lead by example” and “different with a meaning” - which have been foundational to the company for decades. IKEA’s relentless dedication is evident in its daily efforts to make a positive difference in the lives of people and the planet.

Based on the analysis of the eight dimensions, it becomes evident that the values most closely associated with IKEA Portugal, both by name and by their application, are “cost-consciousness”, “caring for people and planet”, and “simplicity”. However, its relevance to the decision-making process when purchasing furniture and decoration products and services ranks fifth. This indicates that, although valued, “simplicity” may not be as critical a factor in the purchase decision compared to other considerations. On the other hand, “cost-consciousness” and “caring for people and planet” emerge as highly decisive factors in this purchasing process. It is apparent that values like “togetherness”, “lead by example”, and “give and take responsibility” have the least association with the IKEA Portugal brand and consequently have minimal impact on the consumer’s purchase decision process compared to the other five values. Despite this, the value “different with a meaning” does not have a strong association with the brand by name, yet it ranks fourth in response to Question 2 and the level of importance to consumers when making their decisions. Additionally, “renew and improve”, although not closely linked to the brand, emerges as the third most influential value in the decision-making process for purchasing furniture and decoration items. This suggests that while certain values may not be directly associated with the brand, they still hold significance for consumers.

In conclusion, this research aimed to ascertain the significance of humanistic values in the purchasing decisions of Portuguese millennial consumers, particularly concerning the IKEA brand. Ultimately, the findings suggest that, in answering the research question, brand values do play a pivotal role in the purchasing decisions of this generation. Specifically, values such as “cost-consciousness” and “caring for people and planet” emerged as key determinants, contributing to a positive overall assessment.

Whether it is at the moment of the purchase decision or even at the start of this process, such as when evaluating alternatives, a brand’s values have an impact on the millennial generation’s choice. Millennials will be more willing to invest in a product or service that allows them to fulfil their “needs for social, economic and environmental justice” (Kotler et al., 2011, p. 4). As such, a brand like IKEA Portugal that presents humanistic values and is committed to a better future and to “creating a better everyday life for most people” can only hope for a continuous increase in sales and, at the same time, a reputation based on transparent and coherent values between the organisation and its consumers and other stakeholders.

Referências

Agrocluster. (2017). Estudo de tendências de consumo: Geração Y millennials. https://agrocluster.pt/estudo-de-tendencias-de-consumo-geracao-y-millennials/ [ Links ]

Baudrillard, J. (1998). The consumer society: Myths and structures. SAGE. [ Links ]

Bond, T. (2021, 1 de outubro). Do company values influence customer acquisition? MyCustomer. https://www.mycustomer.com/customer-experience/engagement/do-company-values-influence-customer-acquisition [ Links ]

Calvo-Porral, C., Pesqueira-Sanchez, R., & Faina, A. (2018). A clustered-based categorization of millennials in their technology behavior. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 35(3), 231-239. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2018.1451429 [ Links ]

Carr, P. (2021, 13 de maio). Consumers are declaring their social values through purchase decisions-Are you listening? ADWEEK. https://www.adweek.com/sponsored/consumers-are-declaring-their-social-values-through-purchase-decisions-are-you-listening/ [ Links ]

Costin, G. (2019, 1 de maio). Millennial spending habits and why they buy. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesbooksauthors/2019/05/01/millennial-spending-habits-and-why-they-buy/ [ Links ]

Cyr, M. G. (2018). China: Hyper-consumerism, abstract identity. Cuaderno de Economía, (78), 195-212. https://doi.org/10.18682/cdc.vi78.3671 [ Links ]

Deloitte. (2022). Striving for balance, advocating for change. The Deloitte global 2022 gen z & millennial survey. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/insights/articles/glob175227_global-millennial-and-gen-z-survey/Gen%20Z%20and%20Millennial%20Survey%202022_Final.pdf [ Links ]

Engel, J. F., Blackwell, R. D., & Miniard, P. W. (1986). Consumer behavior. Dryden Press. [ Links ]

Engel, J. F., Kollat, D. T., & Blackwell, R. D. (1968). Consumer behavior. Holt, Rinehart & Winston. [ Links ]

Enquist, B., Edvardsson, B., & Sebhatu, S. (2007). Values-based service quality for sustainable business. Managing Service Quality, 17(4), 385-403. https://doi.org/10.1108/09604520710760535 [ Links ]

Gonçalves, H. M., Lourenço, T. F., & Silva, G. M. (2016). Green buying behavior and the theory of consumption values: A fuzzy-set approach. Journal of Business Research, 69(4), 1484-1491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.10.129 [ Links ]

Gurău, C. (2012). A life-stage analysis of consumer loyalty profile: Comparing generation X and millennial consumers. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 29(2), 103-113. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363761211206357 [ Links ]

Holt, D. B. (2004). How brands become icons: The principles of cultural branding. Harvard Business Press. [ Links ]

Holt, D. B. (2012). Cultural brand strategy. In V. Shankar & G. S. Carpenter (Eds.), Handbook of marketing strategy (pp. 306-317). Elgar. [ Links ]

Holt, D. B., & Cameron, D. (2010). Cultural strategy: Using innovative ideologies to build breakthrough brands. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Howard, J. A., & Sheth, J. N. (1969). The theory of buyer behavior. John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Howe, N., & Strauss, W. (2000). Millennials rising: The next great generation. Vintage. [ Links ]

Hoyer, W., Maclnnis, D., & Pieters, R. (2012). Consumer behaviour. Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

Huot, R. (2002). Métodos quantitativos para as ciências humanas (M. L. Figueiredo, Trad.). Instituto Piaget. (Trabalho original publicado em 1999) [ Links ]

IKEA. (s.d.-a). Das origens humildes à marca global - uma breve história da IKEA. Retirado a 11 de setembro de 2022, de https://www.ikea.com/pt/pt/this-is-ikea/about-us/sobre-a-ikea-portugal-pub3c09f721 [ Links ]

IKEA. (s.d.-b). Sobre a IKEA Portugal. Retirado a 11 de setembro de 2022, de https://www.ikea.com/pt/pt/this-is-ikea/about-us/sobre-a-ikea-portugal-pub3c09f721 [ Links ]

IKEA. (s.d.-c). A visão e os valores IKEA. Retirado a 14 de setembro de 2022, de https://www.ikea.com/pt/pt/this-is-ikea/about-us/a-visao-e-os-valores-ikea-pub9aa779d0 [ Links ]

IKEA. (2021, 13 de outubro). IKEA Portugal encerra o ano fiscal com 462 milhões de euros em vendas. https://www.ikea.com/pt/pt/newsroom/corporate-news/ikea-portugal-encerra-o-ano-fiscal-com-462-milhoes-de-euros-em-vendas-pub262d5c27 [ Links ]

Kamprad, I., & Torekull, B. (2010). A história da IKEA (M. Andrade, Trad.). A Esfera dos Livros. (Trabalho original publicado em 2006) [ Links ]

Kotler, P., Armstrong, G., Harris, L. C., & He, H. (2020). Principles of marketing. Pearson. [ Links ]

Kotler P., Kartajaya H., & Setiawan I. (2011). Marketing 3.0: From products to customers to the human spirit. John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Kotler, P., Kartajaya, H, & Setiawan, I. (2017). Marketing 4.0: Moving from traditional to digital. John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Kotler, P., Kartajaya, H., & Setiawan, I. (2021). Marketing 5.0: Tecnhnology for humanity. John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Kotler, P., & Keller, K. (2012). Marketing management (14.ª ed.). Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Lacerda, C., & Borges, F. (Eds.). (2017). All about geração millennium: O maior estudo jamais feito em Portugal! CH Consulting; Multidados. [ Links ]

Lemon, K. N., & Verhoef, P. C. (2016). Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. Journal of Marketing, 80(6), 69-96. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.15.0420 [ Links ]

Maslow, A. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, (50), 370-396. [ Links ]

Merck. (2022a, 1 de julho). Os millennials portugueses querem um futuro mais sustentável; já a geração Z prefere que seja mais equitativo e inclusivo. https://www.merckgroup.com/pt-pt/news/merck-survey-o-futuro-que-os-millennials-e-a-geracao-z-da-europa-querem-2022-07-04.html [ Links ]

Merck. (2022b, 5 de setembro). Jovens portugueses são os que, na Europa, fazem mais planos para ter filhos. https://www.merckgroup.com/pt-pt/news/merck-survey-jovens-portugueses-sao-os-que-na-europa-fazem-mais-planos-para-ter-filhos-2022-09-05.html [ Links ]

Nicosia, F. M. (1966). Consumer decision processes: Marketing and advertising implications. Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Santos, S., & Gonçalves, H. M. (2021). The consumer decision journey: A literature review of the foundational models and theories and a future perspective. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 173, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121117 [ Links ]

Sheth, J. N., Newman, B. I., & Gross, B. L. (1991). Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values. Journal of Business Research, 22(2), 159-170. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-2963(91)90050-8 [ Links ]

Twenge, J. M. (2010). A review of the empirical evidence on generational differences in work attitudes. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(2), 201-210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9165-6 [ Links ]

Wellner, A. S. (2003). The next 25 years. American Demographics, 25, D26-D29. [ Links ]

Woo, A. (2018, 4 de junho). Understanding the research on millennial shopping behaviors. Forbes Agency Council. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesagencycouncil/2018/06/04/understanding-the-research-on-millennial-shopping-behaviors/ [ Links ]

Zainuddin, N., Russell-Bennett, R., & Previte, J. (2008, 15-16 de julho). Describing value in a social marketing service: What is it and how is it influenced? [Apresentação de comunicação]. Partnerships, Proof and Practice - International Nonprofit and Social Marketing Conference, Wollongong, Austrália. [ Links ]

Received: October 12, 2023; Accepted: February 16, 2024