Introduction

Specific structures have been set up in France, the support and work assistance establishment (Etablissements et services d’aide par le travail; ESAT; Baret, 2012; Bocquet, 2015; Lajoumard et al., 2019; Zribi, 2012) to promote the social and professional inclusion of people with disabilities. They have the originality of defining a “protected” work framework1, proposing professional actions and deploying individualised and adapted support (Fourdrignier, 2012; Paul, 2002). At the same time, the ESAT are fully integrated into the economic fabric of the territories they are located in (Baret, 2012). Based on the premise that work is a powerful vector of dignity by allowing each person to ex press his or her abilities, this article proposes to address different forms of inclusion resulting from medico-social and professional support for people with disabilities in rural areas: inclusion through work and inclusion through housing and mobility. Based on the results of a research action financed within the framework of a call for projects by the Fondation Internationale de la Recherche Appliquée sur le Handicap (FIRAH; International Foundation of Applied Disability Research), associated with Groupe Agrica, Laser Emploi and Solidel on the general theme “handicap and rural space”, we will focus on the example of the agricultural ESAT of Le Habert, located in Entremont-le-Vieux, in the Savoie region of the Alps, which accompanies people with mental disabilities and/or intellectual disabilities.

We will first focus on the notions of dignity and inclusion to understand to what extent work can enable people with disabilities to conquer the ontological dignity of every human being and find their place in society. Secondly, we will look at the characteristics and particularities of the ESAT Le Habert. Located in the mountains in a rural commune of a little more than 600 inhabitants and managed by an association, it offers, among other things, the possibility for people with mental disabilities and/or intellectual disabilities to work on a dairy farm, to produce cheese and to sell or valorise these products in the commune’s inn managed by the establishment. After the presentation of the participative action-research which is based on semi-directive interviews, we will be interested in the therapeutic and inclusive added value of a rural accompaniment, allowing the accompanied persons to conquer their dignity by linking the feeling of freedom conveyed by the mountain, the feel ing of usefulness and the pride to participate in the functioning of a territory.

Living in housing in the heart of several villages near the ESAT, we have found that, while allowing a balance between support and autonomy, housing was, in addition to work, a vector of inclusion in its own right. Because of the work opportunities it offers and the social networks it allows to develop, if the rural environment is an asset, the question of managing distance, mobility, and accessibility is a real challenge in this sparsely populated environment. As with work and housing, the various mobility assistance measures offered by the institution, including support for obtaining a driver’s license, also act as powerful vectors of autonomy and inclusion.

Theoretical Framework of the Research: Dignity and Professional Inclusion

On December 13, 2006, the United Nations general assembly adopted the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Recalling the principles proclaimed in its charter in the preamble, adopted at the San Francisco conference on October 24, 1945, it insists on all human family members’ dignity. Dignity is the key concept of this convention, which aims to promote, protect and ensure “the full and equal enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms by all persons with disabilities and promote respect for their inherent dignity” (Convention on the Rights of Persons With Disabilities, 2006, p. 4).

However, the content of the concept of dignity, which is extremely imprecise, differs according to the discipline that approaches it (law, bioethics, philosophy...). In the original meaning, as relayed by the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen, 1789; “all citizens being equal ( … ) are equally eligible for all dignities, places and public employment, according to their capacity, and without any other distinction than that of their virtues and talents” (Art. 6), dignity refers to an idea of prestige (Bonjour, 2006). In the 1948 Declaration (Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948; “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights”), the meaning of the term evolves and expands to qualify what is considered sacred in every human being (Weil, 1949). According to Paul Ricoeur (1988), it “is due to the human being by the mere fact that he is human” (pp. 235-236). This conception of dignity as a common good for all explains why, in the history of philosophical thought, the notion has often been associated with the weakest (Bonjour, 2006): this is evidenced, for example, by the works of Lévinas (1996), Steiner (2005) or even Schopenhauer (1840/1978). The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Convention Relative aux Droits des Personnes Handicapées, 2018) is thus intended to be a first step in reducing the social disadvantage suffered by persons with disabilities, as evidenced by preambular paragraph (y):

convinced that a comprehensive and integral international convention to promote and protect the rights and dignity of persons with disabilities will make a significant contribution to redressing the profound social disadvantage experienced by persons with disabilities and will promote their participation, on the basis of equal opportunity, in all spheres of civil, political, economic, social and cultural life, in both developed and developing countries. (pp. 3-4)

The concept of dignity is broader than the law that frames it. As human beings, people with disabilities have the same rights as so-called “able-bodied” people. Therefore, in principle, they should enjoy the same dignity that is ontological to the human being. However, society does not always recognise this equal dignity of people with disabilities and so-called “able-bodied” people. Thus, an employer will often prefer to recruit an “able-bodied” person for equivalent skills rather than a worker with a disability. Even if many obstacles can explain the difficulties of access to employment for these workers in the mainstream environment (Blanc, 2006), the stigmatisation processes they are likely to undergo should not be overlooked.

Interpreted as a stigma (Goffman, 1963/1975), difference leads to a phenomenon of rejection that keeps people with disabilities away from the world of work. They are not employed because they are considered too different, too fragile, too slow, not capable of doing the work required. This presumed incapacity is transformed into indignity: the person is not considered worthy of accessing the prestige, the consecration which is work. Regardless of the real difficulties of access to employment for workers with disabilities, we note that their dignity is affected in all cases: without work, how can one have one’s abilities and usefulness to society recognised? Indeed, if we consider dignity in Boni’s (2006) way as the recognition of the human being - of his body, his mind and his abilities -, if we do not recognise and do not allow the professional abilities of these workers to express themselves, how can we give them back their dignity?

In the scientific literature on disability, the link between work, disability, and dignity has been highlighted, particularly by researchers who worked on structuring a social model of disability in the 1980s (Filiatrault, 2016). For them, particularly those inspired by materialist and neo-Marxist theories such as Finkelstein (1980), social exclusion, the indignity of belonging to society, is directly linked to the capitalist society that excludes them from the production process. This conception of disability originates in an organisation of society structured around non-disabled people, which has the effect of “creating” disability by leaving no room for different people. The emergence of the social model was the foundation of disability studies and allowed a fundamental paradigm shift in the scientific field and, more generally, how society considers disability. In the 1990s, new research postures on disability inspired by postmodern theories appeared.

Giving less importance to social and material factors and more importance to cultural and ideal factors, postmodern theorists of disability studies focus their analysis on the individual, his culture and his lived experience. For them, disability is not a pathological dysfunction; it is not created by oppressive social structures. Rather, it corresponds to the result of cultural and linguistic construction of a set of norms leading to the sidelining of individuals considered different (Gustavsson, 2004). Although they recognise the usefulness of the social model (Shakespeare & Watson, 2001), they criticise the fact that it focuses almost exclusively on society and its organisation and forgets the individual. They also criticise the social model for “focusing on physical disabilities neglecting other disabilities and health problems such as intellectual disabilities, autism, learning disabilities, deafness and transcapacitism”2 (Baril, 2013; Filiatrault, 2016, p. 20).

Beyond these theoretical divergences, in addition to insisting on the role of society acting as a real factor preventing people with disabilities from accessing dignity, Ebersold (2009) emphasises that this social conceptualisation of disability, relayed by several texts and international declarations, has participated in the emergence in the public field, but also political and scientific of the concept of inclusion:

the term “inclusion” is gradually tending to impose itself in the public, scientific or political language in place of that of integration, or even insertion. Inclusion is one of the objectives promoted in 1994 by the Salamanca Dec laration, of the rules for the equalisation of opportunities promulgated by the United Nations in the same year, of the Luxembourg Charter promulgated in 1996 by the European Union, and, more recently, one of the indicators retained by the European Union in the framework of the Lisbon Agenda to evaluate public policies (UNESCO, 1994; United Nations, 1994; European Union, 2002). Its consecration is the result of a movement mobilising actors from the associative world and researchers around a social model of disability that refuses to exclude people with a disability in favor of accept ing them as different. (p. 71)

Unlike integration, which assumes that the origin of social inequalities (which integration aims to correct) lies in the intrinsic characteristics of the group being integrated, inclusion repositions the origin of social inequalities in the conditions of access, the obstacles to participation and the barriers existing within the group in which we wish to include another group.

Since they cannot access their dignity because they are excluded from the world of work or victims of stigmatisation, it is no longer a question of inserting people with disabilities but of including them.

Based on the premise that dignity and inclusion require the recognition of the human being, particularly his capacities, the scientific approach that we have set up within the research-action frameworks links the social model of disability and postmodern conceptions. Approaching the subject through the geographical dimension has led us to deploy several scales of analysis. If the individual, his life trajectory, his daily life and his aspirations have constituted the core of our methodological framework, we have not only focused on individual destinies. By constantly bearing in mind that disability is a social construct, the geographical approach enabled us to question the place occupied by these individuals in the society as a whole, in which they try to be included.

Le Habert, an Agricultural ESAT in the Middle of the Mountains: Production, Processing and Promotion of Farm Work

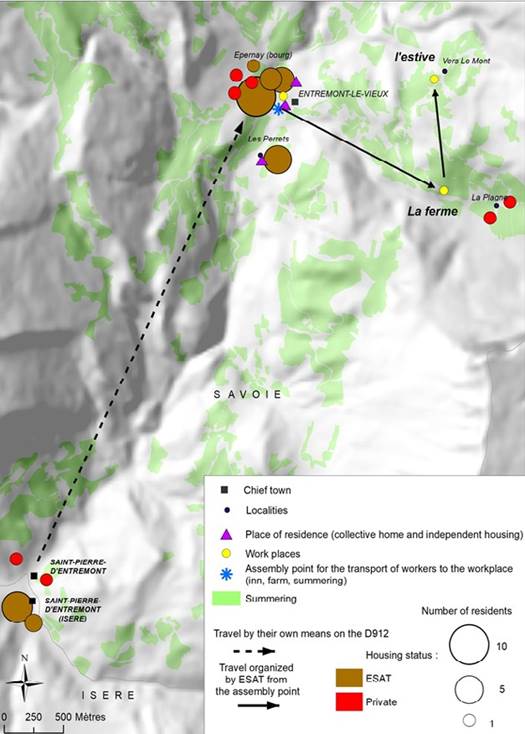

Located at an average altitude of 816m above sea level in the heart of the Chartreuse Regional Natural Park, the ESAT Le Habert is located in the commune of Entremont-LeVieux (Savoie department), which has 651 inhabitants spread over 26 hamlets. It is a relatively isolated commune: only a secondary road (D912), which crosses the valley, links it to Chambéry, some 20km away (Figure 1).

The creation of Le Habert is the result of a reflection by the association Espoir 733, which was looking into the question of support and adapted care for people with mental disabilities. The idea of associating medico-social support and agricultural activity emerged from the example of an integration establishment in the neighbouring department. The location of the ESAT Le Habert, in the commune of Entremont, was explained by the presence of three dairy farms that had to cease their activity for lack of a buyer. The creation of Le Habert thus contributed to maintaining agricultural activity in the area (Figure 2).

Credits. Mauricette Fournier

Figure 2: Support and work assistance establishment Le Habert’s activity sites: Cheese factory

The association’s philosophy is based on the notion of “my life, my choice, my right”. Therefore, the support and care provided are based on the psychosocial rehabilitation concept. This concept is based on a global approach to the person, leading to a holistic knowledge of the situation. This concept of psychosocial rehabilitation tends to reinforce the capacities of each person, with the aim of satisfaction and social stabilisa tion (Bon & Franck, 2018; Boyer, 2011). Thus, the accompanying persons start from the principle that each person has abilities and skills to develop, with respect for the individual, while encouraging him to be an actor of his life.

Today, Le Habert comprises an ESAT with 35 places and one residential home with 29 places. The ESAT accompanies people with psychological disorders and, more specifically, schizophrenia, even if individuals with other disorders can be accommodated. The majority of these people are men, and their age of arrival is between 25 and 35 years old.

The support work is based on agricultural and agri-food activities. First of all, there is the farm where 30 local cows are raised. The milk production is transformed in a cheese-making workshop (production of cheeses, including Bleu de Chartreuse, created by the ESAT, and yoghurts). The products are sold to a local clientele through the ESAT’s store (direct sales) and in various valley stores. A part of the products is reserved for the Auberge des Entremonts, the only restaurant in the commune managed by the ESAT. Finally, the workers with disabilities can provide agricultural and/or environmental services (clearing brush, managing green spaces, pruning vines, harvesting grapes, etc.) for local communities or companies (Figure 3).

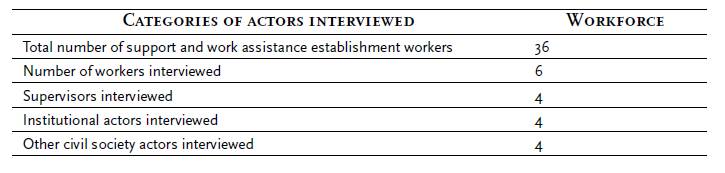

Methodology: A Qualitative Approach

Initially, the action research was based on various voluntary interviews conducted with ESAT workers. Following meetings during which the team presented them with the study’s objectives, the ESAT workers showed a genuine interest in the study, which was reflected in numerous informal exchanges throughout the fieldwork period and in the number of people who agreed to testify and share their experience. Thus, six workers in the livestock and cheese workshop volunteered to participate in the interviews. They were six men aged between 24 and 58 (four of them were in the 45-55 age group). The interviews took place either at the workplace or during break times. However, before the interviews, time was set aside for discussions to get to know the workers’ daily lives and create a link (Table 1).

From a methodological point of view, we cannot ignore the particularity of psychological and mental disabilities in the context of a study based on the words and discourse of the people concerned. Indeed, if mental disability impacts intellectual and learning capacities, communication, socialisation or emotional stability, people suffering from mental disorders are also in a situation of “vulnerability” (Muller, 2011). For the latter, this notion is notably linked to an alteration in their ability to get through a difficult situation, in their relationship with others and with themselves, implying a constantly changing emotional stability. Also, to evolve in the real world, the notion of spatiality and physical and social environment (Fougeyrollas & Noreau, 2007) is essential. The emotional state significantly influences the ability to live in society, perform specific tasks, express oneself or evolve within a group (Pachoud et al., 2009). On the other hand, a secure en vironment favours bonding and exchange.

Therefore, during the interviews, the trust had to be established to facilitate the discussion. Nevertheless, testifying about one’s life path and history mobilises emotions. To ensure a friendly atmosphere was maintained, the interviews were adapted to suit the particulars inherent to each participant. That had the effect of causing a loss of information in certain situations, despite the care taken not to censor or over-frame the exchange to encourage the expression of information.

The interviews carried out with the other actors of the territory aimed to contextualise, at various scales, the testimonies of the workers. Discussions with supervisors close to the interviewees (specialist educators and workshop monitors) made it possible to learn about the measures implemented by the establishment to promote the au tonomy of Le Habert workers. Meetings with staff from the Maison Départementale des Personnes Handicapées de Savoie, da Communauté de Communes Cœur de Chartreuse, do Parc Naturel Régional de Chartreuse e da Chambre d’Agriculture shed light on the anchoring of ESAT in its territory and the relationships established, at the local as well as the departmental level, with institutional actors (mainly local communities). Finally, a few interviews were conducted with town residents to measure their knowledge of ESAT and their image of the establishment and its workers.

Living in the Mountains, Working in Agriculture: Therapeutic Benefits and Inclusion in the Local Economy and Territory

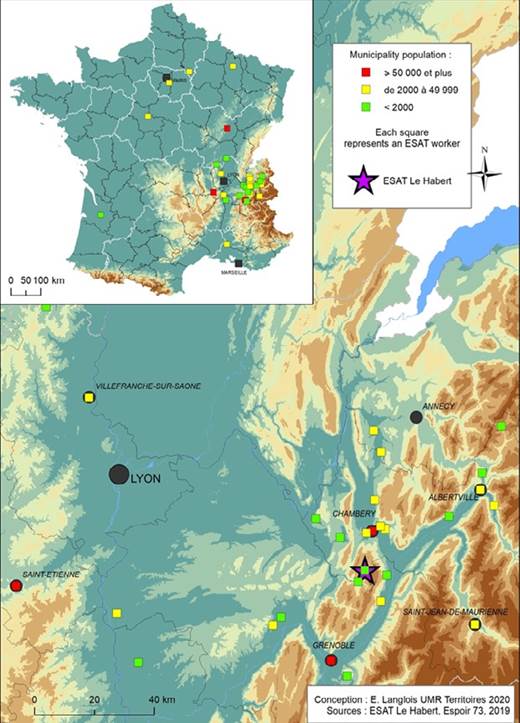

The research sample has five people from the Auvergne Rhône-Alpes region, including two from the Savoie department. The other person came from the Hauts-deFrance region but already lived in the region before entering the facility (Figure 4).

Credits. Eric Langlois

Figure 4: Origin of the workers at support and work assistance establishment Le Habert Note. Each square represents a support and work assistance, establishment worker.

The life courses and the decisions referring to Le Habert, although different, show similarities. Most people have a profile marked by addictions (alcohol, drugs). They have experienced a phase of social breakdown, sometimes involving acts of self-destruction leading to hospitalisations in psychiatry. However, the six interviewed workers chose to come specifically to an agricultural establishment. For three of them, this enthusiasm for the sector can be explained by the fact that they were originally from the area (son of a farmer, former farmer) and the fact that they wanted to return to their roots. “I was born in it ( … ) I have a job, I like it, I like my tarines4” (Pierre5, worker with disabilities, September 2019).

In addition to the well-being of returning to a professional activity, some have highlighted the therapeutic dimension of agricultural work, mainly contact with animals. This example illustrates the powerful vector of dignity that work can represent, reinforcing the self-image.

Taking care of an animal is going to allow them to project themselves onto themselves, but as a result see themselves in the animal and become aware that you also have to take care of yourself to go well in life. (Jacques, workshop instructor, September 2019).

The therapeutic interest of work, specifically agricultural activity, was also underlined to help people find their bearings and organise their daily lives. Indeed, for people who, because of their disorders, may lack reference points, work allows them to regain a rhythm of life: learning to get up again, organising their day, having a daily goal. Beyond these therapeutic aspects, agricultural work on the farm represents an actual means of inclusion.

Throughout the manufacturing process, the valorisation of the work generates a feeling of social utility and inclusion in the local economy and the territory. By raising, transforming and then valorising the farm’s products, the workers have the feeling of being considered as professionals in their own right, with specific know-how. Indeed, working on the farm or in the cheese factory requires organisation, technical skills, and qualities such as patience and organisation.

There is still a lot of technical knowledge. We have to produce milk in accordance with the cheese market, so we don’t let our cows calve in winter. We eat a lot of cheese in the spring, from spring on, in the summer, with all the tourists we have, so we have to have calves at that time. So, you see it’s quite technical, and there is a worker who works on it, on the breeding schedule. So, as a result, the reproduction schedule means the quantity of milk. (Cédric, workshop instructor, September 2019)

For the other three, an upstream internship reinforced the interest in ESAT and its environment. Several people questioned thus underlined their interest in the rural environment, the values associated with agricultural work, the feeling of freedom that comes from living in mountain regions or the importance of evolving in an environment mainly protected from multiple temptations: “far from alcohol and drugs” (José, worker with disabilities, September 2019);

there are the values of the land, ( … ) there we work on things that are a little ancestral. All those who are here have made the choice to orient themselves towards the rural area. ( … ) It may be a way for some to rebuild elsewhere, in a quieter place, far from the demands of the city. (Paul, educator, September 2019)

In addition, the ESAT’s workshops, especially those related to production and manufacturing, require a certain amount of autonomy from the workers. These tasks requiring more autonomy are entrusted to them gradually according to their evolution, which contributes to generating a feeling of self-confidence and a sense of responsibility.

I didn’t trust myself, uh... I had lost my confidence, completely. And then there was a farmer in the valley who got hurt. And my instructor, he called me, he asked me if I wanted to go on secondment, to replace this farmer who had been hurt. So I was always stressed, I didn’t have any confidence in myself, and then I found myself all alone on a farm. And so, well, I managed. So I had everything, so I had to milk, uh, prepare the cows, bring the cows in, prepare the cows, milk them, take care of the milk tank, clean the stations, take care of the little calves, and I did that all by myself. And that freed me from a uh, a big weight that I had inside me. (Mathieu, worker with disabilities, September 2019)

Housing and Mobility: A Double Vector of Inclusion

The question of accessibility, defined by Laurent Chapelon (2014) as “the greater or lesser ease with which [a] place can be reached from one or more other places, by one or more individuals likely to travel using all or part of the existing means of transport” (para. 1), has proved crucial in this research, whatever the scale of analysis.

The notion of accessibility in sparsely populated areas first prompts us to question the configurations of the territory. Indeed, the rural environment often implies a relative distance between places, leading to greater difficulty in travelling. Rural areas are also often characterised by the absence of infrastructure (communication routes) or services (public transport) allowing mobility. Richer and Palmier (2012) refer to the potential of a space to be accessible as “territorial accessibility”. The rural environment in general, specifically the area where ESAT Le Habert is located, has low territorial accessibility given their spatial configurations (distance, lack of infrastructure and services).

If accessibility depends on the territory’s characteristics and on a mobility offer that transcends geographical obstacles, it depends on the actors who wish to move and be mobile. While “accessibility of territories” is a spatial potential, “accessibility of people” is a social potential, which refers to the characteristics of actors, to their “individual or collective capacity to be mobile in space” (Richer & Palmier, 2012, p. 431).

Repositioning the notion of accessibility in rural areas in the context of mental disability leads to questioning the capacity of people to seize the mobility offer and use it to carry out their travels. Indeed, the people accompanied by the ESAT Le Habert and living in a territory with poor accessibility (accessibility of territories) cannot all use a mobility offer to move around (accessibility of people). For example, not all have a driver’s license and a vehicle and do not have the same freedom of movement. While some are autonomous in their travel, others, dependent on existing mobility services, sometimes are unable to reach places that are not served by these services independently.

The concept of motility thus perfectly translates the interaction between accessibility, capacity and autonomy. Proposed by Kaufmann and Jemelin (2004) to describe and analyse the potential of mobility, the notion of motility corresponds to “the way in which an individual or a group makes the field of mobility possibilities their own and uses it to develop projects” (p. 5).

Given their personal problems and the poor intrinsic accessibility of the rural environment, the opening up to work made possible by the ESAT contributes to reinforcing the motility of ESAT workers. Indeed, by helping them acquire a driver’s license, the es tablishment contributes to increasing their “field of possibilities”, reducing their dependence on existing services and generally reinforcing their autonomy (Chavaroche, 2014).

More broadly, it increases their capability, their “substantial freedom to achieve different combinations of functioning” (Nussbaum, 2011, p. 39). Conceptualised by Sen (1985), then by Nussbaum (2006, 2011), the notion of capability allows, like motility, but on a broader scale, to express the interaction between a person’s abilities and the possibilities offered by his or her environment. An increase in capability expresses increased individual capabilities and increased freedoms or opportunities created by a combination of personal capabilities and a political, social and economic environment. By acting on the environment of people with disabilities and stimulating their capabilities, rural ESAT allow more than simple access to dignity: they give the people who are accompanied by them the possibility to enjoy greater freedom of action and choice.

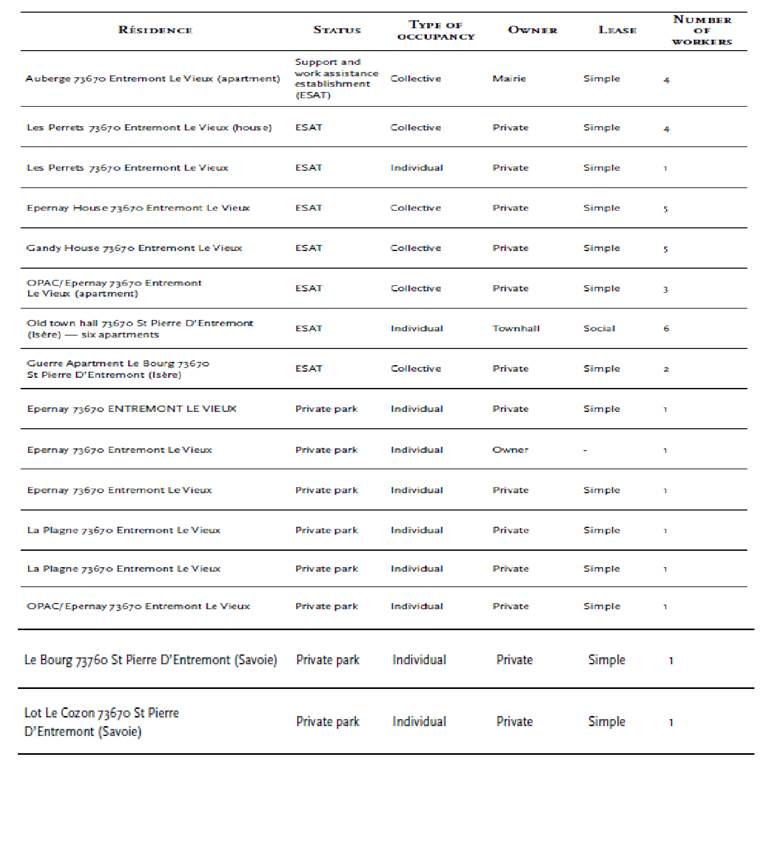

Independent Living: Social Inclusion Through Housing

The majority of Le Habert’s workers live in one of the 13 living units that make up the ESAT’s residential home, located in the communes of Entremont-le-Vieux in Savoie (three houses and three apartments) and Saint-Pierre-d’Entremont in Isère (seven apartments). The houses, which accommodate 14 workers, are rented from private owners. Three apartments located in the heart of the village, also rented by simple lease (to a social landlord and the town hall), provide housing for nine workers (two apartments each accommodate four people and one apartment only one person). In addition, the municipality of Saint-Pierre-d’Entremont (Isère) rents six individual apartments to the ESAT du Habert under a social agreement. Finally, the last apartment, rented from a private owner, allows two workers to share a flat in Saint-Pierre d’Entremont.

The accommodation configuration in small living units promotes autonomy and inclusion in the familiar environment. Indeed, the various small units scattered over the territory facilitate integration into society. This configuration encourages the workers to show initiative and autonomy in daily life. They can lead a professional and social life as independently as possible and can access the services and shops of the community and participate in community activities.

However, the workers of the ESAT are scattered over the territory. In the commune of Entremont-le-Vieux reside, 28 people, divided between the town (21 workers), Les Perrets on the outskirts of the commune (five workers) and La Plagne in the direction of La Ferme (two workers). In addition, 10 workers live 5 km from the ESAT: two in SaintPierre-d’Entremont (Savoie) and six in Saint-Pierre-d’Entremont (Isère). This dispersion of workers raises the question of accessibility and mobility, which appear to be essential, both for daily travel to their place of work and for access to the various shops and services and participation in social life (Table 2).

Getting Around Independently: Spatial Inclusion Through Mobility

Several possibilities are available to the workers to get from their place of residence to the pick-up point, located in Entremont-le-Vieux, where a shuttle system, organised by the ESAT, serves the workshop sites: public transport set up by the Regional Council (Belle Savoie express network), individual hitchhiking or via the Rézo Pouce6, carpooling. However, these solutions do not meet all the travel needs of ESAT workers (medical appointments in a large city, shopping in certain stores, visits to relatives, outings or vacations outside the region, etc.). Increasing their potential for mobility (motility) necessarily involves strengthening their independence.

When they arrive at Le Habert, most workers do not have (or no longer have) a driving license. Therefore, acquiring a driving license is a priority in the structure’s support policy by implementing individualised mobility access projects. The support can take the form of help in preparing for the driving code, contact with driving schools in Chambéry or financial support (up to half the cost of the driving license). That has resulted in an 80% success rate to date within the institution. Thus, four people now have a driver’s license in our panel, and three use their own car. The other three continued to hitchhike, carpool, or use public transportation when possible.

We also encourage them to leave the valley. To go to Chambéry ( … ) passing the license or that the person is autonomous in their travel ( … ) some have two wheels, cars without a license because it’s the location that generates all this. (André, educator, September 2019)

“Stop, everything ( … ) on Saturday I manage to go to Chambéry” (Thomas, worker with disabilities, September 2019).

I’m in the process of getting my license. [Le Habert] doesn’t finance, but they reimburse me uh, half of the lessons I will have taken ( … ) for now, it’s walking, farm vehicle, and then the bus when I have to go to driving school and then on Saturday. (Vincent, worker with disabilities, September 2019)

There I met C who goes to the pool and who is happy, and there is another gentleman who goes to the pool, and as S has a car, they will perhaps after several sessions like that accompanied, go there both by car. (André, educator, September 2019)

This independence acquired or regained during their stay at the ESAT allows the workers to develop their ability to organise their daily lives and take possession of their living environment. This autonomy also represents a means of accessing professional and social integration more easily (Figure 5).

Conclusion

By enabling people with disabilities excluded from the world of work to engage in professional activity, ESAT’s offer them the opportunity to regain their dignity by fully recognising their abilities. Located in a rural mountain environment at an altitude of more than 800 m, the example of the ESAT Le Habert is particularly interesting. The structure offers people with mental disabilities and/or intellectual disabilities inclusion through agricultural work fully rooted in its territory. Having contributed to the maintenance of three dairy farms, the valorisation and transformation of the production carried out by the persons accompanied is generating added value for the territory.

If their work is beneficial for the region (strengthening the economic fabric, maintaining an open landscape), for the clients or people who come to eat at the inn, in return, the ESAT environment constitutes an asset for accompanied workers and their inclusion. Indeed, the example of Le Habert showed that the inclusion of workers in a territory and a system of production, transformation and agricultural valorisation contributed to stimulating self-confidence and generating a strong feeling of social utility. We have also observed that considering the problems of the workers receiving support, the rural environment isolation, the feeling of freedom the mountains provide, the constraints of work and the sense of responsibility it entails all act as a therapeutic tool, contributing to their well-being.

In addition to work, the establishment offers people accommodation in small living units spread out in different villages. That enables them to guarantee real autonomy and inclusion in local social life through accommodation while maintaining the monitoring and support of the ESAT. If the rural environment is an asset for all the elements we have just mentioned, its low population density and the weakness of the collective mobility offer can be, on the contrary, a brake. By helping the workers to obtain their driving license, the institution works towards their autonomy and the reinforcement of their mobility potential (motility). In addition to enabling inclusion through work and housing, the facility ensures spatial inclusion for everyone.

texto em

texto em