Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Vista. Revista de Cultura Visual

versão On-line ISSN 2184-1284

Vista no.9 Braga jun. 2022 Epub 01-Maio-2023

https://doi.org/10.21814/vista.3982

Varia. Articles

From the Walls to the Screen: Street Art, Everyday and Aesthetic Experience in the Virtual Museum of Lusophony

1Centro de Estudos de Comunicação e Sociedade, Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal

This research focuses on the tensions between everyday art, the processes of visibility and invisibility in street art and the aesthetic experience in the virtual environment. The corpus of this study regards the exhibitions: The Silent Voices on Coimbra's Walls and "There Is No Blank Wall I Cannot Draw", both on permanent display in the Virtual Museum of Lusophony on the Google Arts & Culture platform. The Virtual Museum of Lusophony has an interactive, immersive and hybrid structure, merging photographs, sounds, videos and geolocation elements (Google Street View). The secondary goal is to consider the image as a place of experience potentially disruptive of a representative regime of art on behalf of an aesthetic regime.

Keywords: Virtual Museum of Lusophony; street art; everyday art; aesthetic experience

Nesta pesquisa, propomos analisar as tensões entre a arte do quotidiano, os processos de visibilidade e invisibilidade da arte urbana e a experiência estética em ambiente virtual. Este estudo tem como corpus duas exposições: As Vozes Silenciosas das Paredes de Coimbra e "Não Há Muro em Branco Que Eu Não Possa Pintar", ambas em cartaz permanente no Museu Virtual da Lusofonia, na plataforma Google Arts & Culture. Tendo o Museu Virtual da Lusofonia uma composição interativa, imersiva e híbrida, que une fotografias, sons, vídeos e elementos de geolocalização (Google Street View), é objetivo secundário pensar a imagem enquanto lugar de experiência que possui a potencialidade de romper com um regime representativo da arte em prol de um regime estético.

Palavras-chave: Museu Virtual da Lusofonia, arte urbana, arte do quotidiano, experiência estética; arte urbana; arte do quotidiano; experiência estética

Introduction

Wandering through the streets of the cities, one often observes inscriptions and drawings on the walls of the urban architecture. Voices that claim, denounce and point to daily events. Silent and (in)visible, these narratives gain some visibility when they enter the art circuit in the form of photographs. Photographing the trivial, the common, and the everyday is almost inherent to the photographic work, which since its early days has been engaged in capturing images of everyday life in cities, a privileged observatory of certain social and communicational phenomena.

Thinking about the quotidian, one assumes it belongs to the insignificance, to what goes unnoticed and is wrapped in invisibility, as Blanchot (1969/2007, p. 237) suggests. On photography and art of the ordinary, the banal, the everyday, Carvalho (2013, p. 202) points to the photography of the ordinary as a space of aesthetic experiences, strangeness and resistance to the automatisms of everyday life, making us reflect on the practices related to contemporary society.

If the everyday is wrapped in invisibility and if the art of the trivial has the potential to make visible the invisible, it is relevant to think about the process of visibility and invisibility in everyday art. This study relies on the theories of Merleau-Ponty to analyse such issues. In The Visible and the Invisible, Merleau-Ponty (1964/1984) states that seeing would not be opposed to not seeing. Thus the visible and the invisible would complement themselves because it is from what is seen that one can think about what is not seen (p. 232).

Given these assumptions, in this article, we propose to analyse the tensions between the art of the trivial and the everyday life of cities through the exhibitions: The Silent Voices on Coimbra's Walls and "There Is No Blank Wall I Cannot Draw". The exhibitions are part of the Virtual Museum of Lusophony on the Google Arts & Culture1 platform. The Virtual Museum of Lusophony's mission is to promote the countless forms of artistic and cultural expression in the Portuguese-speaking countries by collecting, preserving and disseminating them globally. According to Martins (2015), "the Virtual Museum of Lusophony is, therefore, a mobilising experience of intercultural communication, mutual knowledge and reinforcement of the sense of community in the Lusophone space" (p. 31).

Besides the photographic images, the exhibitions have videos and image geolocation maps from the Street View tool. Google Street View is a resource launched by Google in 2007 and part of the digital platforms: Google Maps and Google Earth. It provides cartography2 with 360º horizontal and 290º vertical panoramic images. The map includes photographs taken randomly and at street level (hence "street view") by vehicles equipped with a device with a nine-eye sphere, and the upper one is a fish-eye lens that captures the view from above (sky). The cameras are integrated with a global positioning system that provides the exact geolocation of the images.

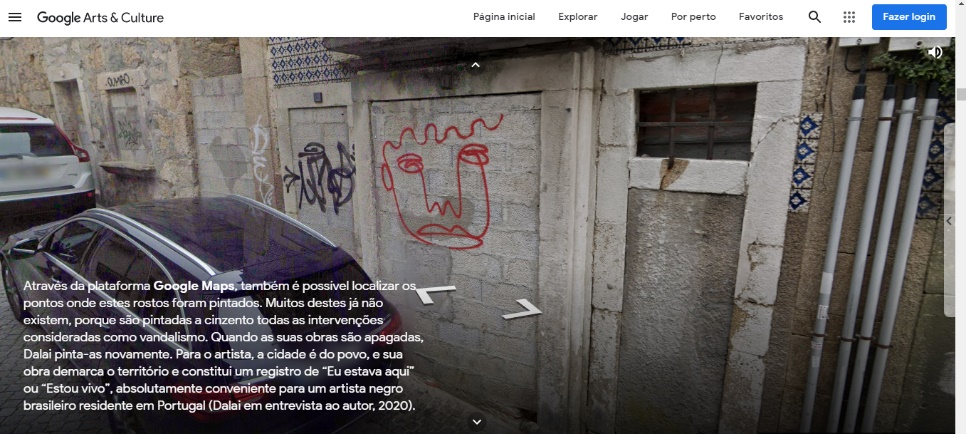

In The Silent Voices on Coimbra's Walls, the photographs and video by Bruno Dias and Rafael Vieira and the Google Street View cartography show drawings and political statements, reflections, claims and social denunciations exposed on the walls of Coimbra, Portugal, a city recognised as a world heritage site by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Among photographs, videos and geolocation elements, how does the aesthetic experience through the screen happen, and what could differ from the sensory experience of seeing the inscriptions when wandering through the city streets? The same questions arise when looking at the exhibition "There Is No Blank Wall I Cannot Draw" by Lucas Reis, which portrays the work of the Brazilian artist Dalai in the streets of Porto, Portugal. Transgressive urban intervention. That is how Dalai defines his art, drawing a tag on the walls of the so-called touristic streets and suggesting a decolonising vision of the city.

The two exhibitions chosen as the corpus for this study are framed in a context of interactivity, immersion and media hybridity since they merge still and moving images and geolocation elements. Thus, the research's secondary goal is to analyse the image as a place of experience, which breaks with the "representational regime" for the sake of an "aesthetic regime of art" (Ranciére, 2000/2005, 2010a, 2003/2011, 2012), where "art is of art, as much as it is something different from art, the opposite of art. It is autonomous to the same extent that it is heteronomous" (Ranciére, 2003/2011, p. 175). Ranciére (2012) also highlights that the sensible experience would not depend on hierarchy issues or the prejudice of power instances (p. 138). Carvalho (2009) states, " the emphasis in the referent, in the adequacy between image and representation, has been increasingly replaced, and images become a place of experience" (p. 142).

From the Walls to the Screen: Street Art, Everyday and Visibility

Urban art, or street art, refers to the cultural demonstration whose setting is the city. Installations, interventions, video mapping, flash mobs, and graffiti, among other cultural practices, belong to this artistic niche. The corpus of this study is two photographic exhibitions that bring to the gallery of the Virtual Museum of Lusophony, on Google Arts & Culture, urban visual interventions such as graffiti and stencils on walls of the traditional streets of Coimbra and Porto, in Portugal. This article does not aim to discuss graffiti or tagging as elements of contemporary art and urban culture, nor will it analyse the conceptual differences between graffiti and tagging. This research seeks to think the everyday art as an element of resistance that can offer aesthetic experience and visibility to ordinary facts and actions.

Inscriptions on walls date back to the cave period when cave paintings were used as a tool for social communication among peers (Gitahy, 1999, p. 11). During the Inquisition in the Middle Ages, priests used bitumen to inscribe elements on the walls of institutions and orders they did not appreciate. Similarly, inscriptions marked the houses of people who were to be attacked and brought into disrepute. After the Second World War (1939–1945), with the introduction of aerosols, spray paint and spray varnish, graffiti became popular and gained an ideal more focused on contestation and politics. So much so that in May 1968, during the French students' revolt, they used graffiti to write their demands on the walls of Paris (Gitahy, 1999, p. 21). Illegal, subversive, transgressive. These are fundamental characteristics of graffiti, an element that stands between power, politics, art and aesthetic experience. On art as politics, Ranciére (2010b) explains that art is born political even before it is artistic.

It is political before anything else in how it shapes a spatiotemporal sensorium that determines ways of being together or apart, outside or inside, in front of or in the middle of... It is political as it cuts through a certain space or a certain time, as the objects it populates this space with or the pace it gives to this time determine a specific experience, following or breaking with others: a particular visibility, a modification of the relations between sensitive forms and regimes of signification. (Ranciére, 2010b, p. 46)

As urban art is part of the everyday life of cities, but also its aesthetics and sensorium, to what extent does the visibility of what sometimes goes unnoticed when we wander through the city's streets occur? By becoming an exhibition and part of the formal arts system, how do the inscriptions stop being invisible and become part of a visible world that one analyse, enjoy and experience? Does viewing the inscriptions in the streets or the gallery change the aesthetic experiences? We may have more questions than concrete answers, but such questions enable the analysis of the artwork of the trivial, the common, and the everyday in contemporaneity.

The everyday has always been of social interest because it is the space of the common, the trivial, where life happens. It is where "we are thus usually ourselves" (Blanchot, 1969/2007, p. 235). A visionary and scathing critic of modernity, Walter Benjamin (1987) analyses the social practice and the changes of an era, as few others do. In essays, letters and fragments, the author focuses on daily life and changes in the city, which in no way resembled the organic and peaceful life of the cities of yesteryear. The modern urban space was full of stimuli that sometimes confused the subject. Luminous panels, signs, advertising, shop windows, cars, trams and a crowd wandering in and out of the streets. These changes led the modern person to physical and perception shocks that could alter social praxis, leading to losses in authentic experience (Erfahung), gradually replaced by living experience (Erlebnis). Without the experience before the facts, the person plunges into everyday life whose elements go unnoticed. The quotidian "does not let itself be caught. It escapes. It belongs to insignificant, and the insignificant has no truth, no reality, no secret, but it is also the place where all signification is possible" (Blanchot, 1969/2007, p. 237).

Despite the apocalyptic thought about the end of the experience in the everyday, it proves to be a relevant space of meaning. So much so that the banal, the common becomes a source of interest to people, be it in modernity or in contemporary times, finding space in photography, theatre, cinema, journalism, and arts in general. If the everyday is for (in)visibility, these are examples of media that offer visibility to the everyday. Carvalho (2013) notes that photography has played a key role in representing everyday life and the ordinary person. Since the early days, photography recorded the changes in the city, the architecture, the characters, and the social practices. Everything was recorded as the inventory of an era, more for its documentary nature than artistic and aesthetic, since only in the 1980s did photography have its aesthetic and artistic potential recognised and is perceived as an object of contemporary art when installed in museums and galleries (Trindade, 2015, p. 67).

If the everyday is insignificant, unnoticed and invisible, by capturing the common "thing" and transforming it into photography, into a work of art, the trivial is offered some visibility. The photography of the everyday leads the subject to strangeness, the possibility of aesthetic experiences, and space of resistance to the automatisms of everyday life (Carvalho, 2013, p. 202). This space of strangeness and resistance to everyday life is reflected in the two exhibitions. The Silent Voices on Coimbra's Walls with photography and video by Bruno Dias and Rafael Vieira and "There Is No Blank Wall I Cannot Draw" with visual interventions' photographs by the Brazilian artist Dalai, in the streets of Porto, Portugal. The photographs are signed by Lucas Reis, Margarida Andresen and Sofia Quintas. Lucas Reis and Margarida Andresen direct the documentary. The exhibitions are part of the Virtual Museum of Lusophony and can be visited permanently on Google Arts & Culture.

Hybridity, Immersion and Interactivity in the Virtual Museum of Lusophony

Both the exhibitions, The Silent Voices on Coimbra's Walls and "There Is No Blank Wall I Cannot Draw", address graffiti as an artistic and political element that can generate a community debate about their proposed issues. They have similar editing features using still photographic images as artistic objects, moving images through audiovisual documentaries and the possibility of accessing maps of the places where the visual interventions are made available through Google Street View. By joining these elements, such exhibitions reiterate the hybridisation of formats, which, according to Fatorelli (2013), expands photographs and gives them other configurations, just as films gain new uses and their own versions when used in galleries and museums. On the threshold, between photography and video, as is the case of Street View; between the virtual and the material, as is the Virtual Museum of Lusophony itself, perceptions tend to be reconfigured towards another aesthetic experience.

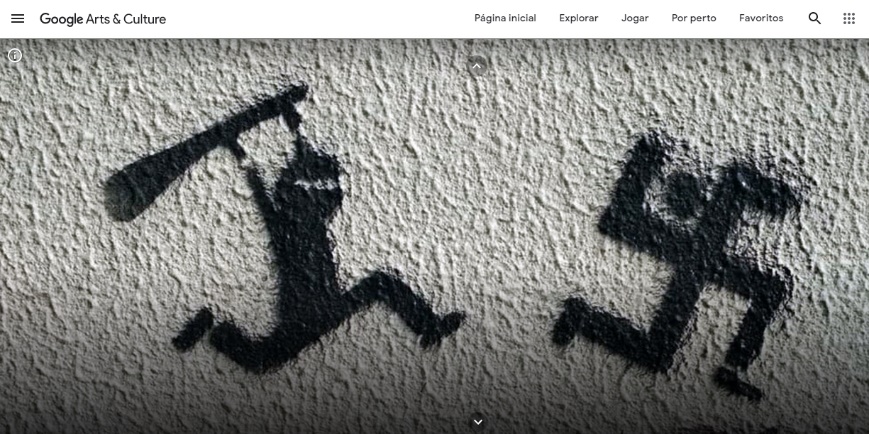

Figures 1, 2, and 3 show three digital media formats used in The Silent Voices on Coimbra's Walls exhibition. The first one refers to a photographic image of a stencil about the fight against Nazism and Fascism (Figure 1).

Credits. Bruno Dias Source. The Silent Voices on Coimbra's Walls

Figure 1 Antifascist activism (2020)

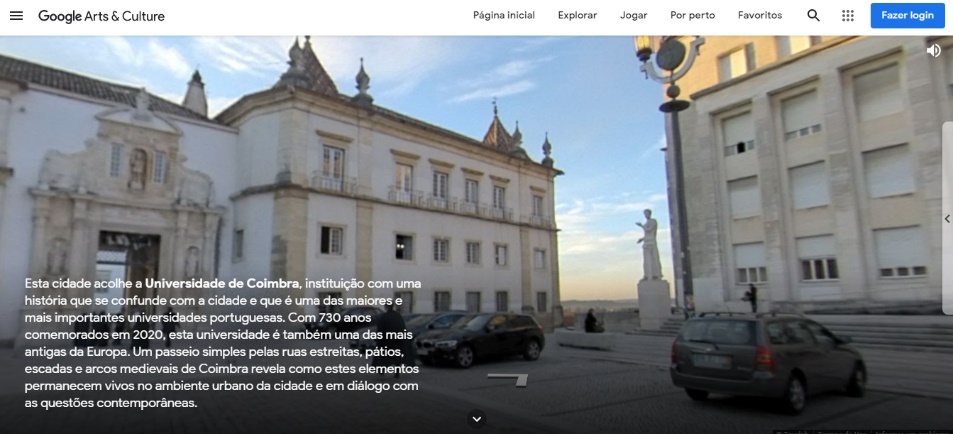

The second image (Figure 2) is a Google Street View cartography screenshot showing the Law School of the University of Coimbra. In this image map, the observer can wander through the spaces and virtually know the place, an interaction and an immersion mediated by the platform.

Source. The Silent Voices on Coimbra's Walls

Figure 2 Google Street View cartography screenshot showing the Law School of the University of Coimbra

The third image (Figure 3) is a screenshot of the first frame of the video Coimbra Street Art, featuring an interview with architect and researcher Rafael Vieira, who studies the communication model of visual interventions on city walls, especially in Coimbra. The images photographed by Rafael Vieira are part of the Coimbra Street Art profile, which has almost 3,000 images and over 2,000 followers on Instagram.

Credits. Bruno Dias/Virtual Museum of Lusophony Source. The Silent Voices on Coimbra's Walls

Figure 3 Coimbra Street Art – Inverview with Rafael Vieira

Although closely related, the narrative of The Silent Voices on Coimbra's Walls is different from that of "There Is No Blank Wall I Cannot Draw". The first reinforces the inscriptions by slogans with themes linked to feminism, racism, exclusion, fascism and certain momentary social concerns, such as social isolation on account of the pandemic related to the coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2). One of Rafael Vieira's concerns in the interview is the transitory character of the inscriptions, which, considered vandalism, are regularly erased by the authorities, but which, according to Rafael, will always exist because it is a form of social protest that transcends time.

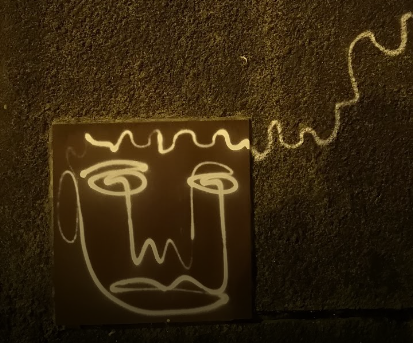

In "There Is No Blank Wall I Cannot Draw", the Brazilian artist Dalai, who lives in Porto, Portugal, proposes a dialogue between graffiti, art, city, power, tourism and gentrification by suggesting a decolonising look at the city. The artist does not inscribe words or punch lines on walls but a drawing that works as a tag (Figure 4) to be spread massively through the streets.

Credits. Sofia Quintas Source. "There Is No Blank Wall I Cannot Draw"

Figure 4 Rua de Raul Dória – Porto

In the video included in the exhibition, Dalai explains that the face he paints is inspired by himself and relates to the idea of expressing himself through the image of "a Black person in a European city". He concludes that the tag "has taught him that it is very important to show who we are and where we come from". The face the artist paints is spread across the main touristic points of Porto. Rua da Infanta Dona Maria, Rua do Pilar, Rua do Mirante, Rua 9 de Julho, Escadas do Codeçal, Rua do Cabo Simão, near the Dona Maria Pia Bridge, and other hotspots in the city, touristic or not.

Besides the photographs, the exhibition has a video documentary (Figure 5) with the same title as the exhibition and maps where the Dalai images are located, made available through Google Street View.

Credits. Margarida Andressen and Lucas Reis/Virtual Museum of Lusophony. Source "There Is No Blank Wall I Cannot Draw"

Figure 5 There's no blank wall I cannot draw

When we observe the image of the artist's tag in Rua do Pilar, for example, we are also given the possibility of virtually immersing in it. When interacting with the exhibition through Street View (Figure 6), it is possible to see Dalai's visual intervention in its location.

In "Everyday Speech", Blanchot (1969/2007) warns us that "the person, well protected within the four walls of its familiar existence, lets the world come to it without peril" (p. 239). That leads us to ponder the possibility of another aesthetic experience through cyberspace as virtual museums, especially those integrated with the Google Arts & Culture platform. They provide the immersion and interactivity of the observer with the artwork, museums, galleries, churches and other public and private cultural facilities whose image is digitally captured by the Street View team and made available through Google platforms (Street View, Maps, Earth, Arts & Culture).

The immersion and interactivity in the Virtual Museum of Lusophony are not only in the map images available through Street View. However, that is where these elements are more easily perceptible. The very concept of a virtual museum bears the immersion aspect related to hypertextuality (hyperlinks), media hybridity in which sounds, still images, moving images, audio, and geolocation, among others, are integrated to provide the user with another experience of the sensorium. The issue of immersive environments is complex and "considers the recurring discourse on the dissolution of boundaries, both from the physical and the points of view of thought, a striking feature of the contemporary" (Carvalho, 2009, p. 141).

Google Arts & Culture (n.d.) conceptualises immersive technology as:

a technology that attempts to emulate a physical world through a digital or simulated world, creating a surrounding sensory feeling, thus creating a sense of immersion. Immersive technology enables mixed reality, a combination of virtual reality and augmented reality or a combination of physical and digital. The term "immersive computing" is effectively synonymous with mixed reality as a user interface in some uses. (para. 1)

Immersion, interactivity and media hybridity are three of the main pillars of the aesthetic experience in the Virtual Museum of Lusophony. It is an experience at another level, which expands the field of visibility and increases the possibilities of the sensorium. Ultimately, the image is itself a place of aesthetic experience, an experience that opens the opportunity for another aesthetic regime that Ranciére (2000/2005, 2010a, 2003/2011, 2012) calls the "aesthetic regime of art".

The Image as a Place of Experience and the Aesthetic Expression of Art

The word "experience" stems from the Latin experientia, which is formed by three fragments: ex (outside), peri (perimeter/boundary) and entia (learning, knowledge). The Priberam dictionary defines the word experience as the "act of experimenting", "rehearsal", and "attempt or the knowledge acquired by practice, study, observation" (Priberam, n.d., Definitions 1-4). Although the studies about experience date back to Aristotle, we will take here the concept of experience by Walter Benjamin, a German philosopher and essayist affiliated with the Frankfurt School and John Dewey, and the University of Chicago, related to pragmatism, to better understand the concept of "aesthetic regime of art" (Ranciére, 2000/2005, 2010a, 2003/2011, 2012) and image as a place of experience (Carvalho, 2009).

Walter Benjamin (1859–1952) was one of the greatest critics of life and art in modernity. He analysed the question of experience as an authentic experience (Erfahung), conceived as something sensory and transmissible by human beings, or by Erlebnis (experience), an individual, internal experience. In several of his essays, Benjamin thought about the loss and poverty of experience, which he called "Erniedrigung", the degradation of experience in modernity, a time in which, according to the theorist, there would be no more experiences to share or convey.

Benjamin's (1987) essay "Experience and Poverty", written in 1933, opens with a parable in which a father reveals to his sons the existence of a treasure buried in the estate's vineyards. When their father passed, the sons dug but found nothing. However, when autumn came, the vineyard bore fruit like no other in the whole land, disclosing the treasure. To this knowledge passed on through the generations, Benjamin calls authentic experience. In the following paragraph, the theorist highlights the loss of experience and cites the silence of soldiers returning from battlefields after the First World War (1914–1918). Even though they had lived through new experiences, it seemed that the soldiers could not narrate the demoralising moments they had gone through.

A generation that had gone to school in horse-drawn streetcars found itself abandoned, homeless, amid a landscape unlike anything else except the clouds and, at its centre, in a force field of destructive rumbles and explosions, the tiny, fragile human body. (Benjamin, 1987, p. 115)

For Benjamin (1987), the war, the shocks of sensibility stemming from the changes of modernity, and the attempt to erase the traces so that no history is left for the future, are potentially destructive to the experience. On the lack of experience, Benjamin further reflects on the loss of this ability in other essays. In "The Storyteller" (Benjamin, 1987), he states that the art of narrating experiences is about to become extinct. When faced with the inability to narrate, the subject would be facing an even greater loss, the tradition essentially linked to the authentic experience. Benjamin argues that with the loss of experience, the person would have become an automaton living the routines imposed by modernity leaving aside the Erfahung (experience) to live the Erlebins (experience). Without tradition and history, the subject would become devoid of memory, devoid of the ability to narrate, of the ability to listen.

However, the theorist believes that some thinkers, artists and architects were already adapting to the new times and cites Paul Klee and Adolf Loos. They would have abandoned the image of the traditional person, "solemn, noble festooned with all the offerings of the past, and turn to the naked person of the contemporary world, a newborn baby in the dirty diapers of the present" (Benjamin, 1987, p. 116). For the construction of another language, poor in experience, since people would be freeing themselves from it for the sake of the poverty of everyday life. However, this degradation could be the start of a new beginning.

Contemporary to Walter Benjamin, John Dewey (1892–1940) thought the notion of experience overlapped with the making of art and the aesthetic fruition in the receptive-perceptive axis of the works of art. In Art as Experience, Dewey (1980, p. 35) highlights the difference between the broadness of the term experience and one experience, in which the experience (broadly) would happen continuously during everyday life, where the subject is faced with the experience all the time, without keeping track. The experience here would be incomplete and resemble the concept of Erlebnis in Benjamin. Whereas in the concept of an experience, the subject would have a quality interaction at a deeper level, a sensible one. "Such an experience is a whole and bears its own individual quality and self-sufficiency. This is an experience" (Dewey, 1980, p. 35).

This individual experience is in the realm of the emotional, the sensible. Through this aesthetic experience, the subject would be able to transform the environment and let itself be affected by it through its sensibility/perception. For Dewey (1980, p. 41), aesthetics is essential to experience. The doing, the suffering and the pleasure are in the same dimension of the aesthetic experience of quality, able to leave emotional marks on the subject. These emotional marks are not linked to a specific span. The aesthetic experience is always in the realm of the sensible and can be short or long-lasting. What is important is the completed act, and the impact experience has. "In fact, emotions are qualities when they are significant in a complex experience that moves and changes. I stress, when they are meaningful, for otherwise, they are but the surges and eruptions of a disturbed child" (Dewey, 1980, p.41).

Dewey (1980, p. 46) complains that the English language does not have a word that combines the concepts "artistic" and "aesthetic". Treating them separately, the artistic being the act of production and the aesthetic the perception and enjoyment of the work, would not encompass the meaning of both as complementary. Art combined with aesthetics is the energy that makes the experience become an experience, eliminating everything that does not contribute to a mutual organisation of the senses.

Although Dewey is considered one of the pioneers in analysing art as an aesthetic experience, in 1793, the German philosopher Friedrich Schiller first showed hints of art as a sensible experience when he wrote 27 letters to his patron establishing a treaty about the aesthetic education of the person (Nicoletti & Berg, 2016, p. 1). In his letters, Schiller, disappointed with the society he lived in, develops the concept of aesthetic experience, a sensible experience able to free man through education in beauty, as a way of moralising society. In his writings, Schiller (1989/2002) separates the human faculties by drives: the sensible drive and the formal drive. There would also be a third drive, the play, responsible for harmonising the sensible and formal drives. A kind of mediator between reason and sensibility (emotion). This play drive is the aesthetic experience in the work of art. An element that could harmonise the society through the moral elevation of the person, who would become the absolute person. Hence the need for people's education in beauty.

The first of these drives, I intend to call sensible, stems from the physical existence of the human being or its sensible nature. It deals with placing it within the limits of time, turning it into the matter: not supplying it with the matter, since this already requires the person's free activity, apprehending matter and distinguishing it from itself as a persistent element ( ... ). The second of these drives, we may call the formal drive, springs from the absolute existence of the human being, or its rational nature, aspiring to set it free, to bring harmony to the diversity of its manifestations, and affirm it in all the transformations of the condition (Schiller, 1989/2002, pp. 63–65).

Drawing on the concepts of sensibility in Emmanuel Kant and Friedrich Schiller, Jacques Ranciére elaborates on the idea of the "aesthetic regime of art". He focuses on the Kant-Schiller binomial because these are the first theorists to study aesthetics as a suspension of a hierarchical regime of authority, a method of equality (Ranciére, 2012, p. 137), as opposed to the regime of representation. To understand what Ranciére refers to as the "aesthetic regime of art", it is relevant to understand some differences between this regime and the representational regime.

Several authors have analysed the representative regime within the social sphere, the language and the arts. We can cite: Michel de Certeau (1975/1982), Serge Moscovici (2001), Paul Ricoeur (2000/2007), Hans-George Gadamer (1960/2008), among others. Grounded in the idea of Aristotelian rhetoric/poetics (Voigt, 2014, p. 308), the representative regime relates to a hierarchy and a value judgment. The representation, which should not be perceived as a copy of the real (mimesis), is conditioned to a referent. This referent allows inferring the representation as a model of truth and method. Gadamer (1960/2008), in Truth and Method, questions the subjectivity and freedom proposed by the concept of aesthetics and the sublime in Kant and Schiller. In the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant (1781/2013) calls sensibility "the capacity to receive (and receptivity) representations of objects according to how they affect us" (p. 15). This pure sensibility would not be attached to a real object. It would be empirical and intuitive and has its freedom preserved. On the other hand, Schiller (1989/2002) portrays aesthetics as the balance between reason and sensibility. Both Kant and Schiller conceive the work of art through sensibility and the impacts aesthetics could promote on the subject and in the world. However, Gadamer (1960/2008) harshly criticises the pure aesthetic model. For the theorist, it would make art exceed the boundary of reality. Nevertheless, he reinforces the idea that art should not be considered a mirror of the real (mimesis of the world) but a representation of an original image, of a referent (p. 202) and, therefore, linked to a traditional model of representation based on hierarchy, authority and value judgment of the work.

Opposed to the concept of a representative regime, we find the aesthetic regime whose main advocate, nowadays, is Jacques Ranciére. Besides him, theorists like Danto (1981), Barthes (1980/1984), Mitchell (2005), and Carvalho (2009), among others, defend the emancipation of the referent, one of the central issues in the "aesthetic regime of art". One of the distinctions between the representational regime and the aesthetic regime is that in representational thinking, the image is produced according to a resemblance, a system of rules based on authority and tradition, while in the aesthetic regime, the image is as a "mute word", which "must be understood in two senses. In the first, the image and the signification of things are inscribed directly on bodies, their visible language to be deciphered" (Ranciére, 2012, p. 22). Further, on the image, Ranciére (2012) recovers the concept of punctum and studium presented by Roland Barthes (1980/1984). One of the issues analysed by Barthes (1980/1984) in Camera Lucida is the evidential nature of the image (studium) and its sensitive mode (punctum), which are not separated from each other. The studium is material and objective. It is the evidential inscription of what is in the image, while the punctum occurs immediately, without the intervention of the word or logical thought. It occurs when the subject is sensitively affected by the image when he/she has an aesthetic experience in which the image survives within him/her and generates a memory.

This assumption about the sublime, the aesthetic, and the affections, as regimes independent of the statute of truth and representation and that date back to Kant (1781/2013) and Schiller (1989/2002), become more evident in contemporaneity, in which we are, at all times, surrounded by images and sensory elements from the most various technological devices. A time where elements such as media hybridisation, immersive and interactive processes in art aim to explore the sensory through aesthetic experience, produced both by the work's author and the observer, who is increasingly led to interact with the work, are more evident and available. The work is often produced through the interaction of an observer who is no longer merely passive and contemplative.

Final Considerations

It is important to note that studies on virtual museums are rather recent since this type of museology was launched after the 1990s. Google Arts & Culture, a platform that brings together virtual museums and cultural facilities worldwide, was created even more recently, in 2011, under the name "Google Arts Project". Google Arts & Culture has been expanding and changing the ways of seeing and feeling the artwork on display through immersion, interaction, and hybrid media, concepts widely studied in contemporary times.

As this practice started in 2011, that is, a little over 10 years ago, the reflection on aesthetic experience, communication, new social practices, and visibility, among others, related to this tool, is made relevant to the field of communication sciences, as well as to the arts. In fact, despite its recent appearance, Google Arts & Culture is quite widespread socially and artistically.

This research and the artistic exhibitions that make up its corpus are developed within the context of the Virtual Museum of Lusophony, a platform of hybrid media, immersion and interactivity. The still and moving images were analysed under the optics of a visual social semiotics methodology. According to Thibault (1991, p. 3), it is beyond the general foundation of semiotics, as a science that studies the sign, but as a social construction of meaning, in which the meaning is given before specific social and cultural practices, acting as "a social and political intervention" (Thibault, 1991, p. 3).

We used a qualitative methodology based on comprehensive bibliographic material to better understand the highlighted concepts. Assuming that the quotidian is immersed in (in)visibility and that the everyday art emerges as a space for resistance and strangeness, generating aesthetic experiences, we focus on Blanchot's (1969/2007) and Carvalho's (2013) studies to analyse street art, in the form of tagging and stencil. This everyday art endures certain invisibility in everyday urban life, but when photographed and inserted in a gallery, it has its aesthetic-artistic character enhanced.

The discussion about visibilities and invisibilities stemmed from Merleau-Ponty's (1964/1984)theory of the visible and invisible, mentioned in the introduction, to state that this work assumes such concepts as inseparable and not opposing to each other. Because the visible is only visible before the invisibility.

As artworks are on display in a virtual museum, hypotheses emerge about media hybridisation, immersion and interactivity, three of the main structures used by Google Arts & Culture to host the exhibitions it mediates. The process of media hybridisation, in the same exhibition, allows the exploration of the observer's sensorium, making the photographs expand, and the videos gain other formats (Fatorelli, 2013). Immersion has been the key feature of virtual museums since their conception, for it promotes the dissolution of borders (Carvalho, 2009). It is in the threshold between the physical and the digital, the real and the simulacrum, to highlight a differentiated aesthetic experience.

In discussing experience, the analysis of experience and the loss of experience in Benjamin (1987) against Dewey's (1980) concept of experience in art and aesthetic fruition were fundamental. Through it, we concluded that an experience would be what is currently called an aesthetic, sublime, sensitive experience, which allows us to think of an "aesthetic regime of art" in Ranciére (2000/2005, 2010a, 2003/2011, 2012).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by national funds through FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, I.P., under the project UIDB/00736/2020 (base funding) and UIDP/00736/2020 (programme funding).

REFERENCES

Barthes, R. (1984). A câmara clara: Nota sobre a fotografia (J. C. Guimarães, Trad.). Nova Fronteira. (Trabalho original publicado em 1980) [ Links ]

Benjamin, W. (1987). Obras escolhidas I: Magia e técnica, arte e política (S. P. Rouanet & J. M. Gagnebim, Trads.; 3.ª ed.). Brasiliense. [ Links ]

Blanchot. M. (2007). A conversa infinita 2: A experiência limite (Vol. 2; J. Moura Jr., Trad.). Escuta. (Trabalho original publicado em 1969) [ Links ]

Carvalho, V. de. (2009). O dispositivo imersivo e a imagem-experiência. Revista Eco-Pós, 9(1), 141-154. https://doi.org/10.29146/eco-pos.v9i1.1064 [ Links ]

Carvalho, V. de. (2013). O cotidiano na fotografia contemporânea: A rua como lugar de experiência na obra de Philip-Lorca diCorsia. In B. Szaniecki, W. D. Lessa, M. Martins, & A. Monat (Eds.), Dispositivo, fotografia e contemporaneidade (pp. 192-207). Nau Editora. [ Links ]

Certeau, M. de. (1982). A escrita da história (M. de L. Menezes, Trad.). Forense Universitária. (Trabalho original publicado em 1975) [ Links ]

Danto. A. (1981). The transfiguration of the commonplace. Havard University Press. [ Links ]

Dewey, J. (1980). Arts as experience. A Wideview/Perigee Book. [ Links ]

Fatorelli, A. (2013). Fotografia contemporânea: Entre o cinema, o vídeo e as novas mídias. Senac Nacional. [ Links ]

Gadamer, H. (2008). Verdade e método (Vol. 1; F. P. Meurer, Trad.). Vozes. (Trabalho original publicado em 1960) [ Links ]

Gitahy, C. (1999). O que é graffiti. Brasiliense. [ Links ]

Google Arts & Culture. (s.d.). Tecnologia imersiva. https://artsandculture.google.com/...1s46xg0?hl=pt [ Links ]

Kant, E. (2013). Crítica da razão pura (M. P. dos Santos & A. F. Morujão, Trads.; 9.ª ed.). Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian. (Trabalho original publicado em 1781) [ Links ]

Martins, M. L. (2015). Média digitais e lusofonia. In M. L. Martins (Ed.), Lusofonia e interculturalidade - Promessa e travessia (pp. 27-56). Húmus. [ Links ]

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1984). O visível e o invisível (J. A. Gianotti & A. M. d'Oliveira, Trads.). Perspectiva. (Trabalho original publicado em 1964) [ Links ]

Mitchell, W. J. T. (2005). What do pictures want? The lives and loves of images. The University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Moscovici, S. (2001). Why a theory of social representations? In K. Deaux & G. Philogène (Eds.), Representations of the social: Bridging theoretical traditions (pp. 18-61). Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

Nicoletti, D. A. R., & Berg, S. M. P. C. (2016, 22-26 de agosto). As cartas de Schiller e a educação estética: Um processo para a criação musical (Comunicação). XXVI Congresso da Associação Nacional de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação em Música, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brasil. https://www.anppom.com.br/...er/download/4473/1405 [ Links ]

Priberam. (s.d.). Experiência. In priberam.org dicionário. Retirado a 10 de março de 2022 de Retirado a 10 de março de 2022 de https://dicionario.priberam.org/experi%C3%AAncia [ Links ]

Ranciére, J. (2005). A partilha do sensível (M. C. Netto, Trad.). Editora 34. (Trabalho original publicado em 2000) [ Links ]

Ranciére, J. (2010a). A poética do saber — Sobre os nomes da história. Urdimento - Revista de Estudos em Artes Cênicas, 2(15), 33-43. https://doi.org/10.5965/1414573102152010033 [ Links ]

Rancière, J. (2010b). Politica da arte. Urdimento - Revista De Estudos Em Artes Cênicas, 2(15), 45-59. https://doi.org/10.5965/1414573102152010045 [ Links ]

Ranciére, J. (2011). O destino das imagens (L. Lima, Trad.). Orfeu Negro. (Trabalho original publicado em 2003) [ Links ]

Ranciére, J. (2012). Le métode de l´égalité. Bayard. [ Links ]

Ricoeur, P. (2007). A memória, a história, o esquecimento (A. François, Trad.). Editora Unicamp. (Trabalho original publicado em 2000) [ Links ]

Schiller, F. (2002). Educação estética do homem: Numa série de cartas (R. Schwarz & M. Suzuki, Trads.; 4.ª ed.). Iluminuras. (Trabalho original publicado em 1989) [ Links ]

Thibault, P. (1991). Social semiotics as praxis: Text, social meaning making and Nabokov‘s Ada. University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Trindade, E. (2015). O olho que tudo vê: A representação das cidades na fotografia de Doug Rickard e Michael Wolf (Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro). http://www.pos.eco.ufrj.br/...a_etrindade_2015.pdf [ Links ]

Voigt, A. F. (2014). História e representação: A abordagem de Jacques Ranciére. Revista de Teoria de História, 12(2), 308-336. https://www.revistas.ufg.br/.../article/view/33453 [ Links ]

Notes

1The migration of the content available on the museum's website to the Google Arts & Culture platform began in September 2019. Alongside the migration, other exhibitions were created, and the partnership was launched on 4 September 2020.

Received: March 25, 2022; Revised: April 18, 2022; Accepted: April 21, 2022

texto em

texto em