Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Análise Psicológica

versão impressa ISSN 0870-8231versão On-line ISSN 1646-6020

Aná. Psicológica vol.38 no.2 Lisboa dez. 2020

https://doi.org/10.14417/ap.1738

The relationship between abusive supervision and organizational trust: The role of subordinates’ self-esteem

A relação entre supervisão abusiva e confiança organizacional: O papel da autoestima dos subordinados

Maria João Velez1

1Instituto Superior de Ciências Sociais e Políticas, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal

ABSTRACT

Interest in abusive supervision (Tepper, 2000) has increased due to its serious personal and organizational costs. As such, there is a need for additional studies that identify the individuals’ factors that can minimize the adverse effects of abusive supervision. Specifically, we predict employee self-esteem as a buffer of the relationship between abusive supervision, organizational trust and in-role behaviors. Additionally, we suggest organizational trust as a possible mechanism linking abusive supervision to in-role behaviors. Our model was explored among a sample of 201 supervisor-subordinate dyads from different organizational settings. The results of the moderated mediation analysis supported our hypotheses. That is, abusive supervision was significantly related to in-role behaviors via organizational trust when employees’ self-esteem was low, but not when it was high. These findings suggest that self-esteem buffers the impact of abusive supervision perceptions on organizational trust, with consequences for performance.

Key words: Abusive supervision, Self-esteem, Organizational trust, In-role behaviors.

RESUMO

O interesse no estudo da supervisão abusiva (Tepper, 2000) aumentou devido às suas consequências nefastas a nível pessoal e custos organizacionais que acarreta. Como tal, são necessários estudos adicionais que identifiquem os fatores individuais passíveis de minimizar os efeitos adversos da supervisão abusiva. Especificamente, propomos que a autoestima dos colaboradores constitui um moderador na relação entre supervisão, confiança organizacional e comportamentos intra papel. Além disso, sugerimos que confiança organizacional é possível mecanismo que vincula a supervisão abusiva a comportamentos intra papel. O modelo proposto foi testado numa amostra constituída por 201 díades supervisor-subordinado de diferentes organizações. Os resultados da análise de mediação moderada suportaram as nossas hipóteses. Ou seja, a supervisão abusiva tem uma relação significativa com comportamentos intra papel através da confiança organizacional quando a autoestima dos colaboradores é baixa, mas não quando a autoestima é alta. Os resultados obtidos sugerem que a autoestima modera o impacto de percepções de supervisão abusiva na confiança organizacional, com consequências para o desempenho.

Palavras-chave: Supervisão abusiva, Confiança organizacional, Autoestima, Comportamentos intra papel.

Abusive supervision, defined as “subordinates’ perceptions of the extent to which supervisors engage in the sustained display of hostile verbal and nonverbal behaviors, excluding physical contact” (Tepper, 2000, p. 178) has received growing research attention over recent years. Examples of these hostile acts include public ridicule, giving the silent treatment, invasion of privacy, taking undue credit, behaving rudely, lying, and breaking promises (Tepper, 2000). A multitude of subordinate outcomes of abusive supervision has been documented and include work-related attitudes, resistance behaviors, deviant behaviors, performance (including both in-role performance contributions and extra-role or citizenship performance), psychological and physical health, and family well-being (for reviews, see Mackey, Frieder, Brees, & Martinko, 2017; Martinko, Harvey, Brees, & Mackey, 2013; Tepper, 2007; Zhang & Liao, 2015).

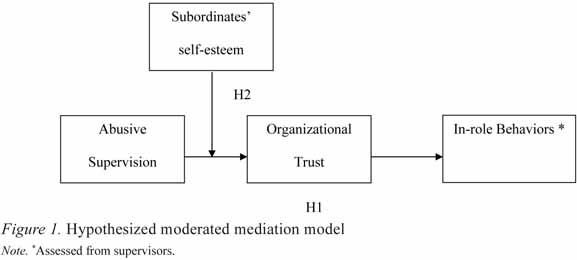

One of the most critical outcomes of employee supervisor mistreatment, for organizations in particular, is reduced job performance, due to its high relevance for individuals and organizations alike (Sonnentag, Volmer, & Spychala, 2008). In-role behaviors refer to the expected tasks of a given role in the work structure. These tasks are formal, that is, they are recognized by the organization as a constituent part of each job (Martin, Guillaume, Thomas, Lee, & Epitropaki, 2016). Harris, Kacmar and Zivnuska (2007) studied the impact of abusive supervision on employee performance and found that employees spend their energy and time to deal with supervisory abusive behaviors, not allowing them to use those resources to entirely focus on the tasks that are formally assigned to them, which has a negative impact on performance. In addition, social exchange theory (Blau, 1964) presupposes a generalized norm of reciprocity (Gouldner, 1960), i.e., when subordinates receive abusive and unfair treatment, they are likely to reciprocate this mistreatment by reducing the quality of their performance (Chen & Wang, 2017; Harris et al., 2007; Zhou, 2016). Despite the assumed relationship between perceived supervisory abuse and lower levels of job performance (see Mackey et al., 2017; Martinko et al., 2013; Tepper, 2007, for a review), few sudies have empirically examined the link between abusive supervision and subordinate job performance (Hoobler & Hu, 2013; as exceptions, see Chen & Wang, 2017; Harris et al. 2007; Neves, 2014; Shoss, Eisenberger, Restubog, & Zagenczyk, 2013). In this vien, the current paper extends these works and attempts to help answer this call by proposing and testing a model that links abusive supervision and in-role behaviors through organizational trust. We then expand this mediation model by proposing and testing the moderating effect of subordinates’ self-esteem in the relationship between abusive supervision and organizational trust, with consequences for in-role behaviors. Additionally, this work extends previous research (e.g., Frieder, Wayne, Hochwarter, & DeOrtentiis, 2015; Harris et al., 2007; Harvey, Stoner, Hochwarter, & Kacman, 2007; Mackey, Ellen, Hochwarter, & Ferris, 2013; Tepper, Carr, Breaux, Geider, Hu, & Hua, 2009; Tepper, Duffy, & Shaw, 2001; Tepper, Henle, Lambert, Giacalone, & Duffy., 2008) by accounting for dispositional factors when exploring subordinates’s responses to abusive supervision. Thus, the current paper attempts to help answer this call by proposing a model that links supervisor abuse and task performance through organizational trust. We test the moderating effect of subordinate self-esteem to contribute to explain the process underlying the abusive supervision and task performance relationship, seeking to examine the active role of employee characteristics in the relationship between abusive supervisory behaviors and subordinate outcomes.

Abusive supervision and organizational trust

Although a variety of definitions for trust exist, one of the most influential definitions of trust defines it as “a psychological state comprising the intention to accept vulnerability based upon positive expectations of the intentions or behavior of another” (Rousseau, Sitkin, Burt, & Camerer, 1998, p. 395). Scholars have offered alternative definitions suggesting that organizational trust is the employees’ belief in the competencies of employees and managers, therefore, employees believe that decisions in the organization are made based on principles of justice, tolerance, ethics and faith in the process of implementation (e.g., Gillespie & Mann, 2004; Yang, 2012).

Two theoretical perspectives pressupposes that trust affects performance through distinct and, potentially, complementary routes (Ferrin & Dirks, 2002). One perspective, the relationship-based perspective, is based on principles of social exchange (Blau, 1964), which presupposes a generalized norm of reciprocity (Gouldner, 1960): when parties provide benefits to one another, there is an expectation of repayment for the benefits received. Therefore, when leaders demonstrate care and consideration, followers are likely to reciprocate by contributing to organizational performance (Gonzalez-Morales, Kernan, Becker, & Eisenberger, 2018). The second perspective, the character-based perspective, implies that followers attempt to draw inferences about their leader’s characteristics (e.g., integrity, dependability, fairness and ability) and that these inferences have consequences for job performance (Ferrin & Dirks, 2002). Following this perspective, when followers expect that their leader will not behave in a hostile manner or in a way that deliberately harms them, this encourages individuals to invest more on required tasks since they believe that the decisions that have a significant impact on them (e.g., promotions, pay, work assignments, layoffs) will be fair (Ogunfowora, 2013). The quality of the relationship between the direct supervisor and the employee plays a key role since the employee generalizes the trust that she/he feels in the direct supervisor to represent the entire organization (Erdem, 2003). Thus, it can be suggested that the process of creating a trusting relationship is a leader’s responsibility (Uslu & Oklay, 2015). As such, previous research has shown that when direct supervisors are able to establish an environment of trust it contributes positively to the feeling of responsibility for work within the organization (e.g., Goodwin, Whittington, Murray, & Nichols, 2011; Otken & Cenkci, 2012). Since high levels of trust in the leader have several positive consequences, it is expected that supervisory abusive behaviors lead to low levels of trust, with negative consequences for task performance.

According to Legood, Thomas and Sacramento (2016), a good place to work for is where employees trust their supervisors and, consequently, their organization. As such, organizations that provide a climate of trust recognized by all organizational members are therefore building added value for the organization as it facilitates performance. These ideas contradict the definition of abusive supervision, since it is characterized by a hostile and unfair climate, harming the well-being of employees, contrary to what a trust climate provides. It can be argued that abusive supervision fails to create a working environment based on the principles of trust and respect (such as sensitivity to the expectations and employee needs) which impair the development of organizational trust and, consequently, it decreases task performance.

Thus, we propose that:

Hypothesis 1: Organizational trust mediates the relationship between abusive supervision and in-role behaviors.

Self-esteem as a moderator

Self-esteem refers to an individual’s general sense of his or her value or worth (Locke, McClear, & Knight, 1996; Rosenberg, 1979) and it has been identified as one of the most important personal resources in the work context (e.g., Bai, Lin, & Wang, 2016). Individuals high in self-esteem perceive themselves as important, meaningful and worthwhile members of their employing organization and rely more on their skills to perform their jobs (Pierce et al., 1993; Rank, Nelson, Allen, & Xu, 2009). Contrarily, individuals low in esteem are affected by their work environments to a greater extent than their counterparts (Pierce, Gardner, Dunham, & Cummings, 1993; Rank et al., 2009). Self-esteem has been significantly related to work-related behaviors and behavioral intentions (for example, performance, organizational citizenship behaviors and turnover intentions), attitudes (such as job satisfaction, organizational commitment and job involvement), mental and physical health (see Bowling, Eschleman, Wang, Kirkendall, & Alarcon, 2010, for a metanalytic review).

Brockner (1983) has shown that individuals high in self-esteem exhibit greater behavioral plasticity (i.e., a more rapid ability to adjust behavior to the situation) than individuals low in self-esteem. This author also proposed that employees low in self-esteem are uncertain about their actions, they need external orientation and present a great need for approval from others, especially from their direct superiors, making them more vulnerable to the negative impact of stressful situations (such as abusive supervision).

Previous research examined the relationship between abusive supervision and self-esteem (e.g., Burton & Hoobler, 2006; Rafferty, Restubog, & Jimmieson, 2010; Schaubhut, Adams, & Jex, 2004; Vogel & Mitchell, 2017). For example, Rafferty et al. (2010) focused on the moderating role of subordinates’ self-esteem in the relationship between abusive supervision and subordinate psychological distress and insomnia. The authors argued that individuals high self-esteem are less vulnerable to the deleterious effects of susceptibility to be influenced by negative feedback and generalize to broader conceptualization of themselves (Rafferty et al., 2010).

Thus, aligned with previous evidence, we suggest the relationship between abusive supervision and in-role behaviors via organizational trust should be affected by subordinate’s self-esteem. When self-esteem is low, a higher level of abusive supervision should be accompanied by reduced organizational trust and thus lead to descreased in-role behaviors. When employee’s self-esteem is high, abusive behaviors should not negatively influence employee performance (through organizational trust), since employees high in self-esteem feel more control over their performance, being less dependent on external approval. Technically, we are describing moderated mediation, since the mediating process that is responsible for producing the effect on the outcome (i.e., in-role behaviors) depends on the value of a moderator variable (i.e., self-esteem) (Morgan-Lopez & MacKinnon, 2006; Muller, Judd, & Yzerbyt, 2005).

Hypothesis 2: The indirect effect of abusive supervision on in-role behaviors through organizational trust is significant when subordinates’ self-esteem is low but not when it is high.

The proposed model is represented in Figure 1.

Method

Sample and procedure

We contacted 12 organizations from different sectors and invited them to participate in the present study, asking their representatives for permission to collect data. Then, we conducted brief meetings with these representatives, where we explained the purpose of the study and its multi-source research method. The representatives of each organization contacted the subordinates in order to invite them to participate in the study. If the subordinates agreed to participate, the researchers then asked the immediate supervisor if he/she was willing to participate. If both were willing to participate, they administered the subordinate survey and the supervisor evaluation form in person in order to guarantee confidentiality. The paper-based surveys were provided only if both employee and supervisor were willing to participate. Each questionnaire was randomly coded in advance with a researcher-assigned identification number in order to match employees’ responses with their immediate supervisors’ evaluations. The researchers administered the questionnaires to the subordinates and their supervisors separately. We personally approached the respondents to brief them about the purposes of the study and to explain the procedures. They received a questionnaire, a return envelope and a cover letter explaining the aim of the survey, the voluntary nature of their participation and reassuring them of the confidentiality of their responses. To reinforce confidentiality, we asked the respondents to seal the completed questionnaires in the return envelopes and to give them directly to the researchers onsite.

We contacted 243 employee-supervisor dyads from 12 organizations, operating in areas such as financial and insurance (33%), higher education (21,5%), health and pharmaceutical (20,4%), transportation (11%), construction (5,2%), manufacturing (4,7%), and retail (4,2%). Two hundred and forty dyads (98,8% of the total number of individuals contacted) agreed to participate and returned the surveys. We excluded 39 dyads because they did not have corresponding supervisors/subordinates’ surveys completed. Thus, our final sample consisted of 201 dyads from 12 organizations, a usable response rate of 82,7% of those originally contacted. The second set of questionnaires was delivered to 17 supervisors. The number of surveys completed by a single supervisor ranged from 1 to 13, with a mean of 2.6. With respect to organizational size, 18% of the dyads came from organizations with less than 10 employees, 63% from organizations with between 10 and 100 employees, and 19% from organizations with more than 100 employees. Overall, 30,8% of the employees did not complete high school, 33,8% of the participants had completed high school and 35,4% had a university degree. Average organizational tenure was approximately 6 years, 55,4% of employees were under 38 years old and most of them were women (61,8%). For supervisors, 15,7% did not complete high school, 40,5% of the participants had completed high school and 45,4% had a university degree. Average organizational tenure was 13 years, 53,5% of supervisors were under 46 years old and 50,2% were men.

Measures

Respondents rated their agreement with each statement using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree) for abusive supervision, job autonomy and production deviance. Supervisors used a 7-point Likert type scale (1=strongly disagree, 7=strongly agree) to assess in-role behaviors. We present the source of the measures, supervisors or subordinates, in parentheses.

Control variables. Gender, age, organizational tenure, education and tenure with the supervisor have been found to be related to organizational trust and in-role behaviors (e.g., Altınöz, Çakıroğlu, & Çöp, 2013; Gilbert & Tang, 1998; Hansen, Dunford, Boss, Boss, & Angermeier, 2011; Ng & Feldman, 2008, 2009, 2010; Roth, Purvis, & Bobko, 2012; Tan & Lim, 2009; Waldman & Avolio, 1986), and therefore we analyzed whether we should control for their influence in our model. Following the recommendations offered by Becker (2005), we controlled for subordinates’ age in our analysis because this was the only control variable significantly correlated with our outcome variables.

Abusive supervision (subordinate measure). Subordinates reported the frequency with which their supervisors presented abusive behaviors using Tepper’s (2000) 15-item scale. Sample items include ‘My supervisor ridicules me’ and ‘My supervisor does not allow me to interact with my coworkers’. Cronbach alpha was .87.

Organizational trust (subordinate measure). A 7-item scale by Gabarro and Athos (1978), and used by Robinson (1996) and Aryee, Budhwar and Chen (2002) was used to measure trust in organization. Example items are ‘My employer is not always honest and truthful’ (reverse-scored) and ‘I believe my employer has high integrity’. The scale’s alpha reliability in this study is 70.

Subordinates’self-esteem (subordinate measure). Respondents measured their current thoughts about their self-esteem using the State Self-Esteem Scale (SSES; Heatherton & Polivy, 1991) consists of 20 items assessing three correlated factors: performance, social, and appearance self-esteem: Performance (e.g., ‘I feel confident about my abilities’), Social (e.g., ‘I feel concerned about the impression I am making’; Reverse scoring), and Appearance (e.g., ‘I feel satisfied with the way my body looks right now’). For this study, only the total SSES score was used. Cronbach alpha was .87.

In-role behaviors (supervisor measure): Supervisors rated their subordinates’ task performance with Williams and Anderson’s (1991) five-item scale. A sample item is: ‘This employee adequately completes assigned duties’. Cronbach’s alpha was .86.

Results

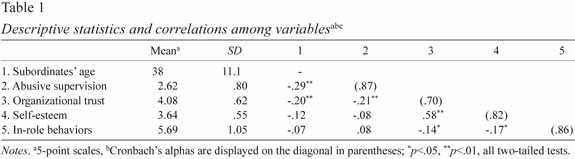

Descriptive statistics and correlations

Means, standard deviations, variable intercorrelations, and scale reliabilities (α) are shown in Table 1. All variables presented reliabilities above the standard .70 (Nunnally, 1978).

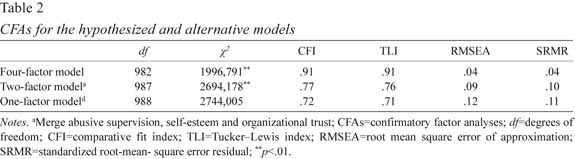

Measurement model

We conducted confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) with AMOS 25 to assess the distinctiveness of the constructs and examine the fit of our hypothesized model. The measurement model included four factors: abusive supervision, subordinates’ self-esteem, in-role behaviors. We examined model fit using the chi-square (χ2), comparative fit index (CFI), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR). The proposed model fit the data reasonably well: χ2(982)=1996,791**, CFI=.91, TLI=.91, RMSEA=.04; SRMR=.04. The four-factor model presented a better fit than the nested models (Table 2), supporting the discriminant validity of these constructs.

Hypotheses testing

To test the proposed model, we used bootstrapping analysis. Bootstrapping offers a straight-forward and robust strategy for assessing indirect effects, mainly mediated moderation effects (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004; Preacher & Hayes, 2004; Preacher, Rucker, & Hayes, 2007; Shrout & Bolger, 2002). Accordingly, we used Hayes’s (2012) Process macro for SPSS to perform our analysis. Predictors were mean centered as recommended by Aiken and West (1991).

To assess hypothesis 1, which indicates that abusive supervision should be negatively related to in-role behaviors via organizational trust, we used model 4 of the Process macro for SPSS (Hayes, 2013). The results showed a direct relationship of abusive supervision with organizational trust (B=-.11, 95% CI=[-.283, -.063]. Regarding the relationship between organizational trust and in-role behaviors, the results were also significant (B=-.23, 95% CI=[-.253, -.035]. We then assessed the indirect effect of abusive supervision on in-role behaviors via organizational trust, which was significant (B=.04; 95% CI=[.003, .103]), confirming this hypothesis.

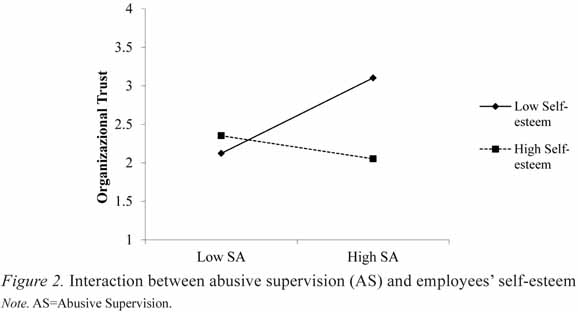

Hypothesis 2 proposes that subordinates’ self-esteem moderates the relationship between abusive supervision and organizational trust, with consequences for in-role behaviors. The results show that self-esteem moderates the relationship between abusive supervision and organizational trust (B=.16; 95% CI=[.005, .326]. We then explored the nature of the interaction by estimating the simple slopes using the procedures recommended by Cohen, Cohen, West and Aiken (2003). Figure 2 illustrates the abusive supervision-organizational trust relationship for different levels of self-esteem: one standard deviation above the mean (i.e., high self-esteem) and one standard deviation below the mean (i.e., low self-esteem). Abusive supervision was significantly related to organizational trust when self-esteem was low (t=3.15, p<.05), but not when self-esteem is high (t=-.52; p>.05) (Figure 2). The difference between slopes was significant (t=2.60, p<.05), suggesting that the strength of abusive supervision-organizational trust relationship is indeed affected by subordinates’ self-esteem.

Hypothesis 2 suggested that self-esteem moderates the indirect relationship between abusive supervision and in-role behaviors via organizational trust. The results indicated that the conditional indirect effect of abusive supervision on in-role behaviors was significant when self-esteem was low (-1 SD; B=.05, 95% CI [.007, .113]), but non-significant when self-esteem was high (+1 SD; B=.00, 95% CI [-027, .059]), supporting hypothesis 2.

Discussion

The current research advances our understanding of how abusive supervision operates by highlighting the role of organizational trust and subordinates’ self-esteem. That is, to the extent employee self-esteem was high, abusive supervision fails to relate significantly to organizational trust and, consequently, not leading to decreased in-role performance. These results are previous studies, such as the study developed by Burton and Hoobler (2006), which proposes that employees high in self-esteem are less prone to be negatively affected by supervisory abusive behaviors, since they are aware of their abilities and they are less affected by the pressure imposed by abusive supervisors. That is, employees high in self-esteem are less vulnerable to the deleterious effects of abusive supervision, since they are less dependent on others and less likely to be influenced by negative criticism, not allowing other people to negatively affect their self-concept (Rafferty et al., 2010).

We extend earlier theorizing in two main aspects. First, we offer a fresh approach to the process of abusive supervision by developing a model based on organizational trust. Responding to previous calls in the literature for an examination of the underlying mechanisms that link abusive supervision to employee job performance (Hoobler & Hu, 2013), this research identified a generative conduit that transmits the effects of abusive supervision to in-role behaviors. Our results show that supervisory abusive behaviors create a hostile climate in which loyalty, goodwill and support are absent, making the organization an unattractive and undesirable entity to be associated with, thereby leading to decreased in-role behaviors. Because supervisors are representatives of organizations (Eisenberger, Stinglhamber, Vandenberghe, Sucharski, & Rhoades, 2002), employees consider that organizations hold the moral and legal accountability for its members’ actions and that they should assume the responsibility to sanction supervisory negative behaviors, and consequently, employees blame their organizations for the occurrence of abusive situations. This assumption is embedded in the organizational support theory (Eisenberger & Stinglhamber, 2011; Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002), which argues that the favorable treatment of supervisors increases the perception of employees that the organization values their contributions and cares about their well-being. In short, from the employees’ point of view, if the organization selects a person to hold a supervisory position and if this person exhibits abusive behaviors, employees assume that the organization tacitly accepts and reinforce this negative behavior.

Second, this study contributes to a growing body of theory and research concerned with abusive behavior in organizations by assessing employee characteristics that may enhance or mitigate the influence of abusive behaviors. In line with previous research (e.g., Rafferty et al., 2010), our findings suggest that abusive supervision is less deleterious when employees perceive themselves to be capable, significant and worthy (Gardner & Pierce, 1998). The transposition of the negative impact of abusive supervision to the organization only occurs when employees fail to perceive themselves as contributing organizational members since they tend to seek the approval of others and respond more strongly to social influence (Gardner & Pierce, 1998; Pierce et al., 1993). This is supported by the pattern of results showing that the relationship between abusive supervision and organization trust varied according to employee self-esteem levels. In other words, abusive supervision only carries disadvantages for organizational trust and individual performance if employees are low in self-esteem. That is, when defining whether they trust their organization, employees examine not only supervisor’s behaviors, but it seems that their self-esteem also plays a pivotal role. Depending on employees’ self-esteem, their work behaviours and attitudes are affected by their social environments to a greater or lesser extent. In summary, these results reinforce the view that abusive supervision does not affect all subordinates in the same way and that individual characteristics should be considered when exploring subordinate responses to abusive supervision (Tepper et al., 2001). Therefore, this study reinforces the results obtained in previous studies (Burton & Hoobler 2006; Rafferty et al., 2010), by demonstrating that subordinates actively contribute to minimize the negative consequences of the abuse process. Thus, high self-esteem can mitigate the influence of abusive behaviors on organizational trust and, consequently, in-role behaviors, since high self-esteem is associated with a positive self-assessment of competence and personal value, making employees high in self-esteem less vulnerable to negative behaviors of abusive supervisors.

Implications for practice

As a practical implication of this study, we emphasize the importance for organizations to develop strategies to promote employee organizational trust and self-esteem, such as offering opportunities for self-direction and self-control, since they promote self-esteem (Pierce & Gardner, 2004; Yam, Fehr, Keng-Highberger, Klotz, & Reynolds, 2016); fostering a climate of autonomy at work, the communication exchanges between employees and supervisors should be of high quality and should demonstrate support to their employees, since these variables also correlate positively and significantly with self-esteem (Bowling & Michel, 2011; Slemp, Kern; Patrick, & Ryan, 2018); developing human resources practices (HR) that aim to promote self-esteem in employees, therefore, organizations should treat their employees with respect, demonstrating appreciation by contributing to meet employees’ belonging needs (Pierce & Gardner, 2004). HR practices should reinforce the quality of relationships between employees and supervisors, which in turn will increase the sense of self-worth, thereby increasing self-esteem and promoting trust in the organization (Liu, Hui, Lee, & Chen, 2013). Finally, organizations should also provide training and education opportunities to improve supervisors’ skills, abilities and abilities, especially in the areas of leadership, participation in decision-making, delegation, communication and justice (Maurer, Hartnell, & Lippstreu, 2017).

An alternative path by which organizations can increase organizational trust and in-role behaviors is discouraging abusive supervision. Organizations should provide management skills training that aims at learning proper ways of interaction with subordinates, as well as abuse prevention training, in order to ensure that supervisors engage in appropriate management practices. However, since it might be difficult to control all negative behaviors, since these behaviors also have deep roots in supervisor’s own personality (e.g., Aryee, Chen, Sun, & Debrah, 2007; Thau, Bennett, Mitchell, & Marrs, 2009), organizations should have explicit and strict policies for punishing individuals who violate these standards. For example, formalized HR practices should adopt a policy of zero tolerance for disruptive behaviors and enforce this policy consistently throughout the organization, while providing formal means for reporting those behaviors and, simultaneously recognizing and rewarding behaviors that demonstrate collaboration, respect and a high regard for interpersonal ethics.

Limitations and direction for future research

Like any research, this study is not without some limitations. Since employees provided information regarding abusive supervision, self-esteem and organizational trust, common method bias may be present. In order to reduce this potential limitation, we obtained evaluations of in-role behaviors from reports of direct supervisors. We also employed statistical remedies to partial out common method variance in our analyses. Using AMOS 25, we estimated a model that included a fifth latent variable to represent a method factor and allowed all the 36 indicators to load on this uncorrelated factor (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, & Podsakoff, 2012). According to Williams, Cote and Buckley (1989), if the fit of the measurement model is significantly improved by the addition of an uncorrelated method factor then CMV may be present. Fit statistics after adding an uncorrelated method factor improved slightly [χ2(352)=1565.902**; CFI=.92; TLI=.93; RMSEA=.04; SRMR=.04]. To determine the extent of the influence of CMV, the variance explained by the method factor can be calculated by summing the squared loadings, in order to index the total amount of variation due to the method factor. In our case, CMV accounted for 13% of the total variance, which is considerably less than the 25% threshold observed by Williams et al. (1989). The results of these analyses suggest that CMV accounts for little variation in the data. Finally, research has shown that common method bias deflates interaction effects, making them more difficult to detect (Busemeyer & Jones, 1983). Nonetheless, future research should strive to include other sources of information (for example, coworkers’ ratings of abusive supervision).

Second, because our study is cross-sectional by design, we cannot infer causality. Indeed, it is possible that the relationship is bidirectional. Despite this possibility, previous studies have made evident the importance of leader´s behavior for determining the level of trust that exists within an organization (e.g., Braun, Peus, Weisweiler, & Frey, 2013) and organizational trust was found to allow employees to focus on the tasks that need to be done to add value to their organization (Mayer & Gavin, 2005). However, we invite future researchers to examine our hypotheses in a longitudinal study. This would help to answer questions related to how abusive supervision and organizational trust perceptions change over time and how the moderating effect of employee self-esteem becomes either pronounced. For example, as time passes by, employees high in self-esteem might become accustomed to abusive supervision as they feel they are better equipped with the necessary resources to cope with the stressor. On the other hand, employees low in self-esteem might feel their inability to cope with abusive supervision aggravates across time.

Another possible direction is to examine these phenomena at different levels (namely work groups, teams or organizations) (Yammarino, Dionne, Chun, & Dansereau, 2005). Researchers may also wish to explore other conditions that influence the strength of the relationship between perceptions of abusive supervision and decreased organizational trust. Although we examined self-esteem, which plays a central role in determining employee attitudes and performance (Nübold, Muck, & Maier, 2013; Pierce & Garden, 2004), other personal features could be explored. As such, we suggest locus of control (Rotter, 1966; Spector, 1982), which describes the extent to which people perceive events in life as contingent on their own actions (i.e., internality) or as contingent upon fate, chance, or powerful others (i.e., externality) (Ng, Sorensen, & Eby, 2006). An internal locus of control has been found to be related to the successful adaptation to stressful work settings and to a lowered perception of work role stress (Lee, Ashford, & Bobko, 1990; Spector, Cooper, Sanchez, O’Driscoll, & Sparks, 2002; Wei & Si, 2013). On the other hand, individuals with an external locus of control are more likely to perceive certain events as stressful, as they feel that the outcomes of the situations are controlled by luck, destiny or powerful others (Reknes, Visockaite, Liefooghe, Lovakov, & Einarsen, 2019).

Finally, we encourage future research to examine how the level of perceived abuse varies with the level of in-role behaviors. It is possible that this relationship presents a feedback loop, where abusive supervision leads to decreases in task performance, which in turn promotes higher levels of abusive supervision. Future work would benefit from the use of cross-lagged longitudinal or experimental designs to draw stronger inferences regarding causality and to fully understand how this process operates.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the current study extends research on abusive supervision by providing fresh insights into the effects, mechanisms, and boundary conditions of abusive supervision, offering relevant implications for theory, research and practice. Specifically, these findings contribute to the literature concerning abusive supervision by proposing organizational trust constitutes an important mechanism linking abusive supervision to employee performance, in the extent that employees view their supervisor as representative of the organization and supervisory abusive behaviors negatively affects employees’ view of their organization. Our results draw attention to previously unexamined buffers (i.e., employees’ self-esteem) in the relationship between abusive supervision and in-role behaviors. This study provides the bases for practical interventions that have the potential to mitigate the adverse consequences of abusive supervision, particularly through strategies aimed to promote employee organizational trust and self-esteem. There is clearly more work to be done in this area, but our research takes a much-needed step toward exploring the important role that employee characteristics and perceptions play in moderating the negative effects of abusive supervision.

References

Aiken, L., & West, S. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Altınöz, M., Çakıroğlu, D., & Çöp, S. (2013). Effects of talent management on organizational trust: A field study. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 99, 843-851. [ Links ]

Aryee, S., Budhwar, P., & Chen, Z. (2002). Trust as a mediator of the relationship between organizational justice and work outcomes: Test of a social exchange model. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 267-285. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1002/job.138 [ Links ]

Aryee, S., Chen, Z., Sun, L., & Debrah, Y. (2007). Antecedents and outcomes of abusive supervision: Test of a trickle-down model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 191-201. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.191 [ Links ]

Bai, Q., Lin, W., & Wang, L. (2016). Family incivility and counterproductive work behavior: A moderated mediation model of self-esteem and emotional regulation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 94, 11-19. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2016.02.014 [ Links ]

Becker, T. (2005). Potential problems in the statistical control of variables in organizational research: A qualitative analysis with recommendations. Organizational Research Methods, 8, 274-289. [ Links ]

Blau, P. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New York, NY: Wiley. [ Links ]

Braun, S., Peus, C., Weisweiler, S., & Frey, D. (2013). Transformational leadership, job satisfaction, and team performance: A multilevel mediation model of trust. The Leadership Quarterly, 24, 270-283. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2012.11.006 [ Links ]

Bowling, N. A., Eschleman, K. J., Wang, Q., Kirkendall, C., & Alarcon, G. (2010). A meta‐analysis of the predictors and consequences of organization‐based self‐esteem. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83, 601-626. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1348/096317909X454382 [ Links ]

Bowling, N. A., & Michel, J. S. (2011). Why do you treat me badly? The effects of target attributions on responses to abusive supervision. Work & Stress, 25, 309-320. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2011.634281 [ Links ]

Brockner, J. (1983). Low self-esteem and behavioral plasticity: Some implications. Review of Personality and Social Psychology, 4, 237-271. [ Links ]

Burton, J. P., & Hoobler, J. M. (2006). Subordinate self-esteem and abusive supervision. Journal of Managerial Issues, 3, 340-355. [ Links ]

Busemeyer, J. R., & Jones, L. E. (1983). Analysis of multiplicative combination rules when the causal variables are measured with error. Psychological Bulletin, 93, 549. [ Links ]

Chen, Z. X., & Wang, H. Y. (2017). Abusive supervision and employees’ job performance: A multiple mediation model. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 45, 845-858. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.5657

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Eisenberger, R., & Stinglhamber, F. (2011). Perceived organizational support: Fostering enthusiastic and productive employees. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Books. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1037/12318-000 [ Links ]

Eisenberger, R., Stinglhamber, F., Vandenberghe, C., Sucharski, I. L., & Rhoades, L. (2002). Perceived supervisor support: Contributions to perceived organizational support and employee retention. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 565-573. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.565 [ Links ]

Erdem, F. (2003). Optimal trust and teamwork: From groupthink to teamthink. Work Study, 52, 229-233. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1108/00438020310485958 [ Links ]

Ferrin, D., & Dirks, K. (2002). Trust in leadership: Meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 611-628. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.611 [ Links ]

Frieder, R., Wayne, A., Hochwarter, W., & DeOrtentiis, P. (2015). Attenuating the negative effects of abusive supervision: The role of proactive voice behavior and resource management ability. The Leadership Quarterly, 26, 821-837. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.06.001 [ Links ]

Gabarro, J., & Athos, P. (1978). Interpersonal relationships and communication. New York: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Gardner, D. G., & Pierce, J. L. (1998). Self-esteem and self-efficacy within the organizational context: An empirical examination. Group & Organization Management, 23, 48-70. [ Links ]

Gilbert, J. A., & Tang, T. L. (1998). An examination of organizational trust antecedents. Public Personnel Management, 27, 321-338. [ Links ]

Gillespie, N. A., & Mann, L. (2004). Transformational leadership and shared values: The building blocks of trust. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 19, 588-607. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940410551507 [ Links ]

Gonzalez-Morales, M. G., Kernan, M. C., Becker, T. E., & Eisenberger, R. (2018). Defeating abusive supervision: Training supervisors to support subordinates. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23, 151-162. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000061 [ Links ]

Goodwin, V. L., Whittington, J. L., Murray, B., & Nichols, T. (2011). Moderator or mediator? Examining the role of trust in the transformational leadership paradigm. Journal of Managerial Issues, 23, 409-425. [ Links ]

Gouldner, A. (1960). The norm of reciprocity. American Sociological Review, 25, 165-167. [ Links ]

Hansen, S. S., Dunford, B., Boss, A., Boss, R. R., & Angermeier, I. (2011). Corporate social responsibility and the benefits of employee trust: A cross-disciplinary perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 102, 29-45. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0903-0 [ Links ]

Harris, K. J., Kacmar, M. K., & Zivnuska, S. (2007). An investigation of abusive supervision as a predictor of performance and the meaning of work as a moderator of the relationship. The Leadership Quarterly, 18, 252-263. [ Links ]

Harvey, P., Stoner, J., Hochwarter, W., & Kacmar, C. (2007). Coping with abusive supervision: The neutralizing effects of ingratiation and positive affect on negative employee outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 18, 264-280. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.03.008 [ Links ]

Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. Manuscript submitted for publication. [ Links ]

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Heatherton, T. F., & Polivy, J. (1991). Development and validation of a scale for measuring state self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 895-910. [ Links ]

Hoobler, J. M., & Hu, J. (2013). A model of injustice, abusive supervision, and negative affect. The Leadership Quarterly, 24, 256-269. [ Links ]

Lee, C., Ashford, S., & Bobko, P. (1990). Interactive effects of “type A” behavior and perceived control on worker performance, job satisfaction, and somatic complaints. Academy of Management Journal, 33, 870-881.

Legood, A., Thomas, G., & Sacramento, C. (2016). Leader trustworthy behavior and organizational trust: The role of the immediate manager for cultivating trust. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 46, 673-686. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12394 [ Links ]

Liu, J., Hui, C., Lee, C., & Chen, Z. X. (2013). Why do I feel valued and why do I contribute? A relational approach to employee’s organization‐based self‐esteem and job performance. Journal of Management Studies, 50, 1018-1040. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12037

Locke, E. A., McClear, K., & Knight, D. (1996). Self-esteem and work. In C. Cooper & I. T. Robertson (Eds.), International review of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 1-32). Chichester: Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Mackey, J., Ellen III, B., Hochwarter, W., & Ferris, G. (2013). Subordinate social adaptability and the consequences of abusive supervision perceptions in two samples. The Leadership Quarterly, 24, 732-746. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.07.003 [ Links ]

Mackey, J. D., Frieder, R. E., Brees, J. R., & Martinko, M. J. (2017). Abusive supervision: A meta-analysis and empirical review. Journal of Management, 43, 1940-1965. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315573997 [ Links ]

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39, 99-128. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4 [ Links ]

Martin, R., Guillaume, Y., Thomas, G., Lee, A., & Epitropaki, O. (2016). Leader-member exchange (LMX) and performance: A meta‐analytic review. Personnel Psychology, 69, 67-121. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12100 [ Links ]

Martinko, M. J., Harvey, P., Brees, J. R., & Mackey, J. (2013). A review of abusive supervision research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34, S120-S137. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1888 [ Links ]

Maurer, T. J., Hartnell, C. A., & Lippstreu, M. (2017). A model of leadership motivations, error management culture, leadership capacity, and career success. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 90, 481-507. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12181 [ Links ]

Mayer, R. C., & Gavin, M. B. (2005). Trust in management and performance: Who minds the shop while the employees watch the boss?. Academy of Management Journal, 48, 874-888. [ Links ]

Morgan-Lopez, A., & MacKinnon, D. (2006). Demonstration and evaluation of a method for assessing mediated moderation. Behavior Research Methods, 38, 77-87. [ Links ]

Muller, D., Judd, C., & Yzerbyt, V. (2005). When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 852-863. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.852 [ Links ]

Neves, P. (2014). Taking it out on survivors: Submissive employees, downsizing, and abusive supervision. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 87, 507-534. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12061 [ Links ]

Ng, T. W. H., & Feldman, D. C. (2008). The relationship of age to ten dimensions of job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 392-423. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.2.392 [ Links ]

Ng, T. W. H, & Feldman, D. C. (2009). How broadly does education contribute to job performance?. Personnel Psychology, 62, 89-134. [ Links ]

Ng, T. W. H., & Feldman, D. C. (2010). Organizational tenure and job performance. Journal of Management, 36, 1220-1250. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309359809 [ Links ]

Ng, T. W., Sorensen, K. L., & Eby, L. T. (2006). Locus of control at work: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 27, 1057-1087. [ Links ]

Nübold, A., Muck, P. M., & Maier, G. W. (2013). A new substitute for leadership? Followers’ state core self-evaluations. The Leadership Quarterly, 24, 29-44. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2012.07.002

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Ogunfowora, B. (2013). When the abuse is unevenly distributed: The effects of abusive supervision variability on work attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34, 1105-1123. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1841 [ Links ]

Otken, A. B., & Cenkci, T. (2012). The impact of paternalistic leadership on ethical climate: The moderating role of trust in leader. Journal of Business Ethics, 108, 525-536. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-1108-2 [ Links ]

Pierce, J. L., & Gardner, D. G. (2004). Self-esteem within the work and organizational context: A review of the organization-based self-esteem literature. Journal of Management, 30, 591-622. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jm.2003.10.001 [ Links ]

Pierce, J. L., Gardner, D. G., Dunham, R. B., & Cummings, L. L. (1993). Moderation by organization-based self-esteem of role condition-employee response relationships. Academy of Management Journal, 36, 271-288. [ Links ]

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual review of psychology, 63, 539-569. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452 [ Links ]

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 717-731. [ Links ]

Preacher, K., Rucker, D., & Hayes, A. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42, 185-227. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/00273170701341316 [ Links ]

Rafferty, A., Restubog, S., & Jimmieson, N. (2010). Losing sleep: Examining the cascading effects of supervisors’ experience of injustice on subordinates’ psychological health. Work and Stress, 24, 36-55. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/02678371003715135

Rank, J., Nelson, N. E., Allen, T. D., & Xu, X. (2009). Leadership predictors of innovation and task performance: Subordinates’ self-esteem and self-presentation as moderators. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 82, 465-489. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1348/096317908X371547

Reknes, I., Visockaite, G., Liefooghe, A., Lovakov, A., & Einarsen, S. V. (2019). Locus of control moderates the relationship between exposure to bullying behaviors and psychological strain. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01323 [ Links ]

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 698. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.698 [ Links ]

Robinson, S. (1996). Trust and breach of psychological contract. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41, 574-599. [ Links ]

Rosenberg, M. (1979). Conceiving the self. New York: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., & Camerer, C. (1998). Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Academy of Management Review, 23, 393-404. [ Links ]

Roth, P. L., Purvis, K. L., & Bobko, P. (2012). A meta-analysis of gender group differences for measures of job performance in field studies. Journal of Management, 38, 719-739. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310374774 [ Links ]

Rotter, J. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs, 80, 1-28. [ Links ]

Schaubhut, N., Adams, G. A., & Jex, S. M. (2004). Self-esteem as a moderator of the relationships between abusive supervision and two forms of workplace deviance. [ Links ] Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Industrial Organizational Psychology, Chicago.

Shoss, M. K., Eisenberger, R., Restubog, S. L. D., & Zagenczyk, T. J. (2013). Blaming the organization for abusive supervision: The roles of perceived organizational support and supervisor’s organizational embodiment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98, 158-168.

Shrout, P., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422-445. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422 [ Links ]

Slemp, G. R., Kern, M. L., Patrick, K. J., & Ryan, R. M. (2018). Leader autonomy support in the workplace: A meta-analytic review. Motivation and Emotion, 42, 706-724. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-018-9698-y [ Links ]

Sonnentag, S., Volmer, J., & Spychala, A. (2008). Job performance. In C. L. Cooper & J. Barling (Eds.), Sage handbook of organizational behavior (vol. 1, pp. 427-447). Los Angels, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Spector, P. E. (1982). Behavior in organizations as a function of employee’s locus of control. Psychological Bulletin, 91, 482-497.

Spector, P. E., Cooper, C. L., Sanchez, J. I., O’Driscoll, M., & Sparks, K. (2002). Locus of control and wellbeing at work: How generalizable are Western findings. Academy of Management Journal, 45, 453-466.

Tan, H. H., & Lim, A. K. H. (2009). Trust in coworkers and trust in organizations. Journal of Psychology, 143, 45-66. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3200/JRLP.143.1.45-66 [ Links ]

Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43, 178-190. [ Links ]

Tepper, B. J. (2007). Abusive supervision in work organizations: Review, synthesis, and directions for future research. Journal of Management, 33, 261-289. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206307300812 [ Links ]

Tepper, B., Carr, J., Breaux, D., Geider, S., Hu, C., & Hua, W. (2009). Abusive supervision, intentions to quit, and employees’ workplace deviance: A power/dependence analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 109, 156-167. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2009.03.004

Tepper, B. J., Duffy, M. K., & Shaw, J. D. (2001). Personality moderators of the relationships between abusive supervision and subordinates’ resistance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 974-983. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.5.974

Tepper, B. J., Henle, C. A., Lambert, L. S., Giacalone, R. A., & Duffy, M. K. (2008). Abusive supervision and subordinates’ organization deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 721-732.

Thau, S., Bennett, R., Mitchell, M., & Marrs, M. (2009). How management style moderates the relationship between abusive supervision and workplace deviance: An uncertainty management theory perspective. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 108, 79-92. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2008.06.003 [ Links ]

Uslu, F., & Oklay, E. (2015). The effect of leadership leadership on organizational trust. In E. Karadağ (Ed.), Leadership and organizational outcomes (pp. 81-95). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [ Links ]

Vogel, R. M., & Mitchell, M. S. (2017). The motivational effects of diminished self-esteem for employees who experience abusive supervision. Journal of Management, 43, 2218-2251. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314566462 [ Links ]

Waldman, D. A., & Avolio, B. J. (1986). A meta-analysis of age differences in job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 33-38. [ Links ]

Wei, F., & Si, S. (2013). Tit for tat? Abusive supervision and counterproductive work behaviors: The moderating effects of locus of control and perceived mobility. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 30, 281-296. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-011-9251-y [ Links ]

Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behavior. Journal of Management, 17, 601-617. [ Links ]

Williams, L. J., Cote, J. A., & Buckley, M. R. (1989). Lack of method variance in self-reported affect and perceptions at work: Reality or artifact?. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 462. [ Links ]

Yam, K. C., Fehr, R., Keng-Highberger, F. T., Klotz, A. C., & Reynolds, S. J. (2016). Out of control: A self-control perspective on the link between surface acting and abusive supervision. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101, 292-301. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000043 [ Links ]

Yammarino, F. J., Dionne, S. D., Chun, J. U., & Dansereau, F. (2005). Leadership and levels of analysis: A state-of-the-science review. The Leadership Quarterly, 16, 879-919. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.09.002 [ Links ]

Yang, Y. C. (2012). High-involvement human resource practices, affective commitment, and organizational citizenship behaviors. The Service Industries Journal, 32, 1209-1227. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2010.545875 [ Links ]

Zhang, Y., & Liao, Z. (2015). Consequences of abusive supervision: A meta-analytic review. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 32, 959-987. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-015-9425-0 [ Links ]

Zhou, L. (2016). Abusive supervision and work performance: The moderating role of abusive supervision variability. Social Behavior and Personality, 44, 1089-1098. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2016.44.7.1089 [ Links ]

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to: Maria João Velez, Instituto Superior de Ciências Sociais e Políticas, Universidade de Lisboa, Campus Universitário do Alto da Ajuda, Rua Almerindo Lessa, 1300-663, Lisboa, Portugal. Email: mvelez@iscsp.ulisboa.pt

Submitted: 27/07/2019 Accepted: 31/12/2019